Man ponders by coincidence. Nature knows better. The difference can sometimes be unfathomable.

Late December . . . The Maryland Shores. . . Snowfall. . .

Mystic, mesmeric, beckoning. Almost eight decades along for this wayfaring, wildfowling warrior — and still, when too infrequently it comes — the most magically essential ingredient of the gum-boot and gunning lifeway.

Mystic, mesmeric, beckoning. Almost eight decades along for this wayfaring, wildfowling warrior — and still, when too infrequently it comes — the most magically essential ingredient of the gum-boot and gunning lifeway.

Just the mere possibility. Never the more thrillingly when it thinks to arrive a coincidental caller upon one of the most perennially hopeful trips of the year.

The livened anticipation, the timeless yearning to abandon camp and comfort, to save the fire, layer up, pull on wetboots and woolen mittens, toss on a scarf, gather up the gear, slap on a beaten, old canvas hat and slicker, brace the damp, frigid air, hurry out and be gone. To be there, when it begins. With the first improbable flake, and then the second and third, before abruptly the air is alive, the certainty pings wonderfully against your face, while in the stairwells of your mind your prospects are transposed to the faultlessness of a Reneson painting, and imagination conjures the perfect day:

Ablind again in its virginal world, listening to its lonesome whisper against cane and cattail, watching its peripatetic gather, stall and swirl over troubled, graywater, over the tack and swing of the decoys in the first bare gasps of dawn, somewhere lost among the dizzying hurl of its oncoming rush the rent and restlessness of passing birds, wedge after wedge. Stoop after stoop, then . . . each rushing and rocking drunkenly, suddenly, out of the churning gloam . . . volleys of teal, billets of Ho’ace’s “mallets,” vanguards of pins, or armies of bluebills and cans.

Ablind again in its virginal world, listening to its lonesome whisper against cane and cattail, watching its peripatetic gather, stall and swirl over troubled, graywater, over the tack and swing of the decoys in the first bare gasps of dawn, somewhere lost among the dizzying hurl of its oncoming rush the rent and restlessness of passing birds, wedge after wedge. Stoop after stoop, then . . . each rushing and rocking drunkenly, suddenly, out of the churning gloam . . . volleys of teal, billets of Ho’ace’s “mallets,” vanguards of pins, or armies of bluebills and cans.

The hunts run by. So many hunts run by. Sometimes by the seasons, and then, will come the one. When upon the cold gray invitation of a solemn afternoon, seemingly countless homecoming wings will cleave the heavens, plummeting in through the flat and huddling gunmetal sky. Wave after wave. As every soulful element that can be stuffed in a wildfowler’s rucksack — mind or matter — melts in place and perfection to heart, and it can be no better. Except that it can . . . when in swirling white magic upon that already splendored ascension of exhilaration falls the crowning advent of snow.

My, oh, my.

Until, almost incredibly one clabbered day, imagination is afforded a holiday and reality is gifted the field. At last, it’s here for real. It was born in the misty-gray light of the natal morn, in that lingering suspension of time that under a cold, clabbered sky uncertainly wrestles daylight from darkness . . . the first lonely flakes sifting almost imperceptibly by, beyond the rime-spattered windowpanes of the lodge.

The possibility adrift, sleep thwarted by the child-like wistfulness of the prospects, we had slept fitfully, the three of us. Excited as if we would as lads that extraordinary day again accompany our fathers and grandfathers the many years ago.

We had risen in the darkness, gathered to an oil-lit kitchen, breakfasted before the hearth of a blazing fire, to herald its coming . . . if in fact it should. And now myself, my erstwhile gunning compadres Bob Timberlake and Eddie Smith — 234years of wildfowling indenture between us — clustered in boyhood wonder before a window, joyfully welcoming its arrival. Watching in glee as the shards grew to a chorus, then to swelling, swirling flurries, cavorting about the teasing wind.

Bob sailed joyfully off into reminiscence, of the rare other days in his 82 years when Fate had smiled so fortuitously. Eddie, across his 76, recalled the few of his own, offering in the soaring moment an amicable bit of philosophy.

It’s what old men do.

“When I was a boy,” he said, “My Dad would tell me that snow was the frozen reincarnation of the Hunter’s Moon. I loved them both. Then one day I saw them together in the same sky.”

He paused a moment, considering.

“It never changed my mind.”

The flurries were beautifully thickening now, to oncoming, drifting clouds, beginning to blanket the circular pathway at the porch of the lodge. Our hearts were in collective revelry. Sweet Jesus. What a day lay in store.

We were shooting at one of the most iconic and coveted waterfowl holdings on the Eastern Seaboard. Would bide the morning, rest the flooded fields until nooning. Join the rest of our party at the Main Lodge later in the morning. Take the myriad homecoming flights that surely now would arrive in staggering numbers through the afternoon.

Meanwhile, we pulled by the chairs, settled back with cups of steaming java and cider, savoring the anticipation, jabbering anxiously. Killed several hack-sacks of make-believe ducks and geese. Watched the snow grow.

Finally, and at last at 1:30 and, after bountiful and exquisite culinary fortification, we were in our pit-blind, roofed-over hoary and white, the outer world beyond our darkened hide an inviting pocket of open water amid the standing cane and swirling snow. Under a lowering sky. Decoys adrift, vividly at work in capricious inscriptions authored by the north wind.

Finally, and at last at 1:30 and, after bountiful and exquisite culinary fortification, we were in our pit-blind, roofed-over hoary and white, the outer world beyond our darkened hide an inviting pocket of open water amid the standing cane and swirling snow. Under a lowering sky. Decoys adrift, vividly at work in capricious inscriptions authored by the north wind.

All else about us lay ice-bound, the temperature having dropped since dawn, standing now mid-20s, plummeting by the half-hour.

If ever there was a waterfowler’s dream, here it was, and surely we would be that day among God’s chosen few.

Through the afternoon, we waited anxiously on, guns ready, though the birds had not come. Had not come rocking inface-on out of the gloam. All we watched was the snow pelting so wonderfully down, and the ice grow on my whiskers. Waiting and waiting, still knowing, still believing.

But dreams do not always “beautifully arc across the years” — or the hours, as the case may be — as Louis L’amour once poignantly observed. Despite all good industry and reasoning, the best of them sometimes stall and crash, mid-flight. Though should you have wasted upon us that particular day the caution, we would not have received it. For we were far too taken by coincidence and perception to hear or heed.

But dreams do not always “beautifully arc across the years” — or the hours, as the case may be — as Louis L’amour once poignantly observed. Despite all good industry and reasoning, the best of them sometimes stall and crash, mid-flight. Though should you have wasted upon us that particular day the caution, we would not have received it. For we were far too taken by coincidence and perception to hear or heed.

So that when the witching hour came for hoards of homing birds, it never came. On into a frigid dusk, through the gloriously swirling snow, they never came.

“All flights cancelled,” Bob declared.

As night closed, we trudged through the blustery, white and whirling netherworld to the lodge, numb with cold and disbelief, conceding at last what we refused to deny before. I glanced at the thermometer on the wall as we stomped the snow off our boots. It shivered at 22.

As night closed, we trudged through the blustery, white and whirling netherworld to the lodge, numb with cold and disbelief, conceding at last what we refused to deny before. I glanced at the thermometer on the wall as we stomped the snow off our boots. It shivered at 22.

A half-hour later, amber glass in hand and still thawing before the fire, we discussed in company with our gunning companions the incredible proposition of it all . . . that upon such a storybook day the birds did not fly.

“When it’s this cold in these conditions, they don’t,” Larry Hindman, for many years Chief Waterfowl Biologist for the Maryland DNR, avowed. “Below 24 degrees, they don’t fly.”

Here’s a man who should know, we thought to ourselves.

Still our minds fought the supposition. We discussed later — the three of us, when all others had retired — our rare hunts in snow across the many years, each wrapped in exceptional gunning, splendored wings and wonder. Then had to admit in each instance the temperature stood cordially in the high 20s.

Still our minds fought the supposition. We discussed later — the three of us, when all others had retired — our rare hunts in snow across the many years, each wrapped in exceptional gunning, splendored wings and wonder. Then had to admit in each instance the temperature stood cordially in the high 20s.

In extreme inclement and low-20s atmospheric conditions, do their wings ice over, disrupting wind-foil? Was this an Eastern Seaboard phenomenon? What of the West and its commonly glacial envelopments?

On we vexed, pondering the imponderable. Before we were forced back to center . . .

The birds didn’t fly.

Perhaps it brings us home to this. Aside symmetry and design, Nature abhors consistency. Consistency gets. you killed. Any behavioral habit and pattern among its creatures that affords repetitive cognitive predictability by a predator species is only very rarely in the playbook. And then, most frequently by mistake. The wisest and wiliest of its disciples, fur or fowl, acquires this wisdom, adheres to it unerringly, or dies.

As humans, we have grown far too tame to remember, or retain the instinct, to be right every time. There’s always “the 24-degree wild card.” That shuts aside the arrogance, that keeps the wonder in it all, that keeps us going . . .and questioning.

Eyes weary, exhausted by the day and dilemma, we closed our impossible discussion at midnight.

Eyes weary, exhausted by the day and dilemma, we closed our impossible discussion at midnight.

As Bob banked the fire, Eddie stepped to the window. It was strangely lit by a faint halo of light. He said nothing for a moment, still nothing, then quietly motioned us over.

High in the eastern sky, the clouds were breaking. There, as they parted, stood the great, icy-silver globe of a full moon.

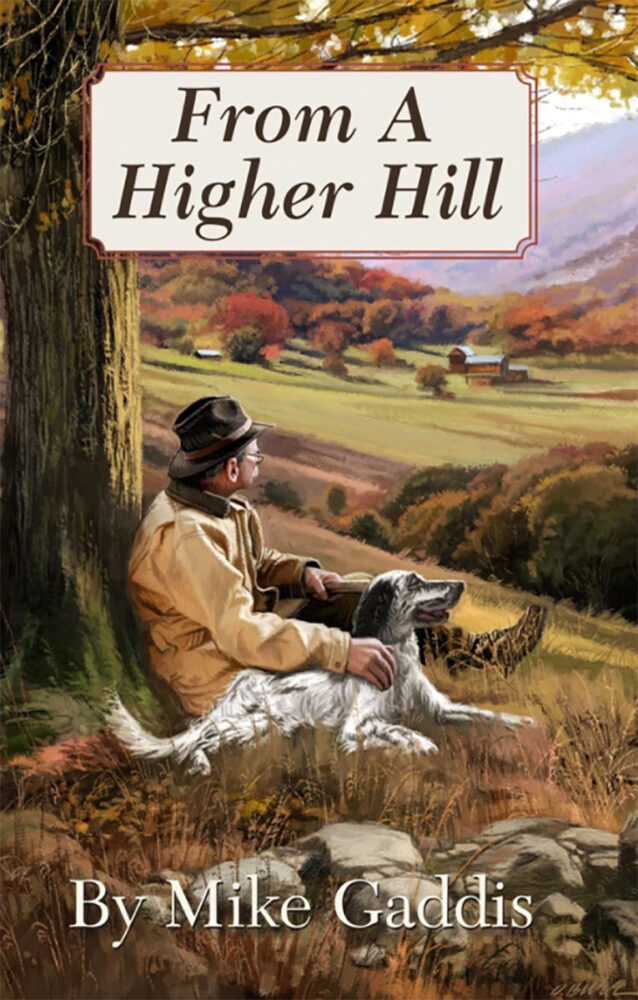

Life can be likened to ascending a mountain. The higher you climb, the more years you have beneath you, the farther you can see, the more unobstructed the view, the more you understand.

Life can be likened to ascending a mountain. The higher you climb, the more years you have beneath you, the farther you can see, the more unobstructed the view, the more you understand.

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now