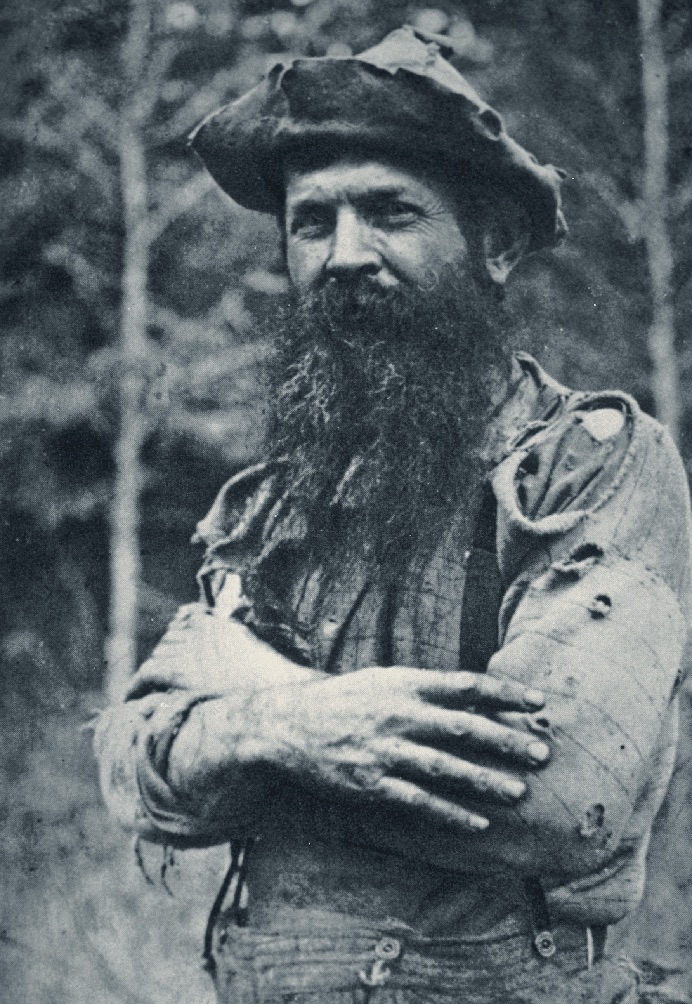

This photograph of Lilly was taken in December 1906, one year before his famous Louisiana bear hunt with President Theodore Roosevelt. Lilly was headquartered in East Texas at the time.

After the honorable David Crockett of Tennessee, Ben Lilly was said to be the greatest bear hunter in American history. He reputedly killed more bears with a knife in hand-to-hand combat than Ol’ Davy ever attempted to “grin” down. In truth, Ben Lilly no doubt killed more black bears and mountain lions, or panthers, as he called them, during his lifetime than any hunter in history.

Realizing in his late 20s that he yearned for a life in the wilderness and that he could indeed make a living by hunting “varmints,” he became very skilled at tracking down black bears, mountain lions and eventually, a small number of western grizzlies. A deeply religious man who refused to hunt on the Sabbath, Lilly truly believed that eradicating the land of bears and panthers was his God-given duty, and he dedicated his life to that pursuit.

Ben Vernon Lilly (1856-1936) was born in Wilcox County, Alabama. His family migrated to Kemper County, Mississippi, where he spent most his boyhood. He was raised with a strong Christian ethic. Lilly’s father, Albert, was a blacksmith, and young Ben took to the trade and learned it well.

When Lilly was 12, his parents sent him to a military academy in Jackson, Mississippi, where he promptly ran away. His whereabouts remained unknown to the family for nearly a decade until his bachelor uncle and namesake, Vernon Lilly, ran into him by chance in Memphis, Tennessee, where he was working in a blacksmith shop. Uncle Vernon offered his 23-year-old nephew a job on his thriving cotton farm in Morehouse Parish, Louisiana. Within a year, Uncle Vernon died, and Lilly inherited the farm.

In 1880, Lilly married Lelia Bunckley. Some claimed she was a little “tetched” in the head. Years later, Lilly jokingly referred to her as “the daughter of Sodom and Gomorrah.”

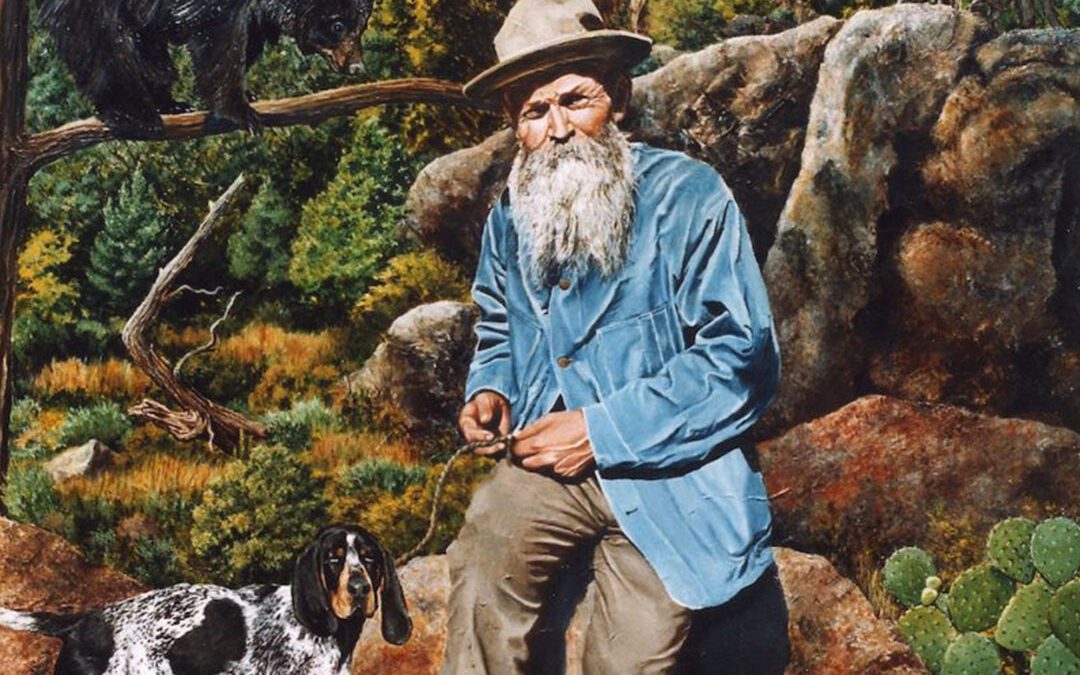

Renowned artist John Seerey-Lester painted The Bear-Slayer for his Legends of the Hunt book. It depicts Lilly at one of his camps surrounded by his hounds and gear. Note the huge leg-hold bear trap.

Lilly tried to farm, but his heart was never in growing cotton. He spent most of his time in the nearby swamps and canebrakes chasing wild “critters.” He also did a little blacksmithing on the side, mostly for his own purposes.

Throughout his long hunting career, he was well-known for forging his own hunting knives and steel traps. Known as the “Lilly” version of a Bowie knife, he sometimes made gifts of his knives to friends and ranch owners who hired him. Lilly knives became cherished possessions.

One day at the farm, he had a chance encounter with a black bear. During the ensuing scuffle, he ended up killing the “varmint” with one of his handmade knives. The experience changed his life. He had found his true calling. The thrill of the hunt beckoned and, in due time, he would heed its call.

Lilly never adjusted well to the idea of domestic tranquility. He was much more content to be alone in some remote bear camp deep in the swamp, gazing up at the stars with his beloved hounds.

One humorous yet almost believable “tall tale” about Lilly’s married life has Lelia sending him out to shoot a chicken hawk that was wreaking havoc among the barnyard fowl. He didn’t return home for almost two years. When she asked where he’d been, he shrugged and said, “That ol’ hawk just kept a’flyin.”

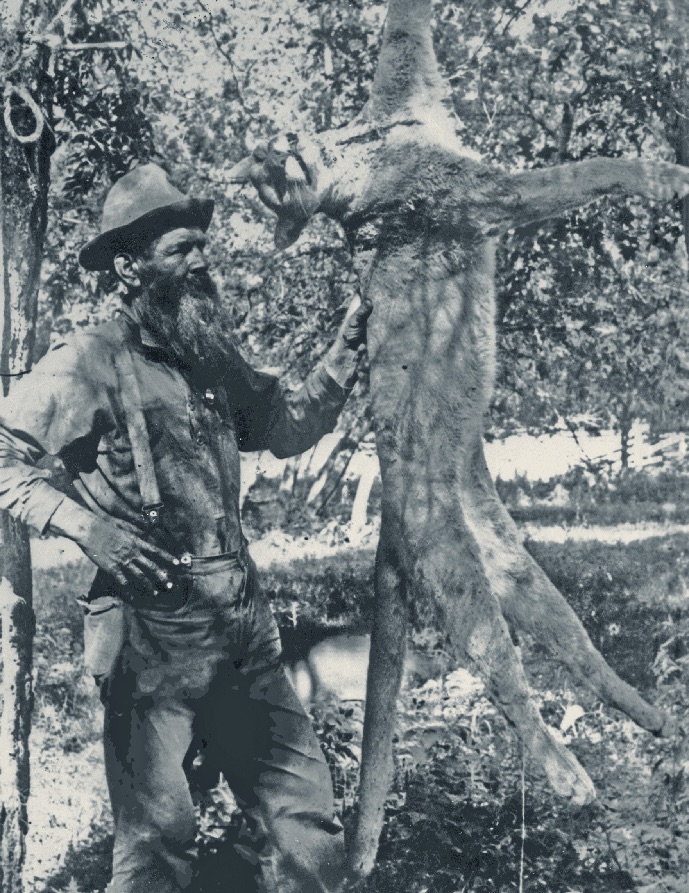

This photograph of Lilly and a mountain lion appeared in the January 1920 issue of Illustrated World magazine along with a story by Lilly.

It’s a wonder he came back at all. The marriage ended in divorce, and Lelia was later committed to an asylum. Lilly remarried in 1891 and moved to Mer Rouge, Louisiana. By the end of the century, he and his second wife, Mary Sisson, had three children.

Lilly made a stab at trading cattle and selling timber, but he began to spend most of his time in the dense canebrakes hunting deer, ’gators and waterfowl for the market and rooting out bears and the few surviving panthers that were becoming increasingly rare in southern Louisiana. Sometimes he’d be gone for weeks. He hunted black bears for their meat and panthers wherever he encountered them, simply because he believed they “needed killin’.”

In 1901, Lilly gave everything he owned to Mary and headed for the thickest Louisiana canebrakes he could find, taking only his rifle, a couple of good hounds and the clothes he was wearing. He was 45 years old.

By a stroke of luck, he soon ran into Ned Hollister, a well-known naturalist who was working in Louisiana on behalf of the Bureau of Biological Survey. Hollister collected bird and mammal specimens for the U.S. National Museum in Washington, D.C. (later known as the Smithsonian Institute). Recognizing Lilly’s great skills as a woodsman and hunter, Hollister taught Lilly how to preserve various specimens, and Lilly soon found himself engaged in a profitable new sideline that lasted for many years.

From 1904 to 1920, Lilly procured nearly 200 specimens for the National Museum, mostly mammals. The long list of species he collected first from Louisiana, and later in Texas, Mexico, Arizona and New Mexico, included several dozen whitetail deer and black bears, more than 40 mountain lions, three grizzlies (one in Chihuahua, Mexico), numerous bobcats, four ocelots, seven red wolves in Louisiana, three “lobo” wolves farther west, several coyotes and numerous species of small mammals, including raccoons, skunks, bats, squirrels and gophers.

Always trying to stay a step or two ahead of that ever-growing curse known as “civilization,” Lilly grew restless and left Louisiana around 1906.

For the next few years, he shared a hunting camp with Ben and Bud Hooks in the Big Thicket country of East Texas. Lilly and the Hooks brothers hunted down the few remaining black bears and panthers in the area. To his credit, as soon as he began making decent money collecting fees and bounties hunting panthers and bears, he sent most of it home to help support Mary and the children.

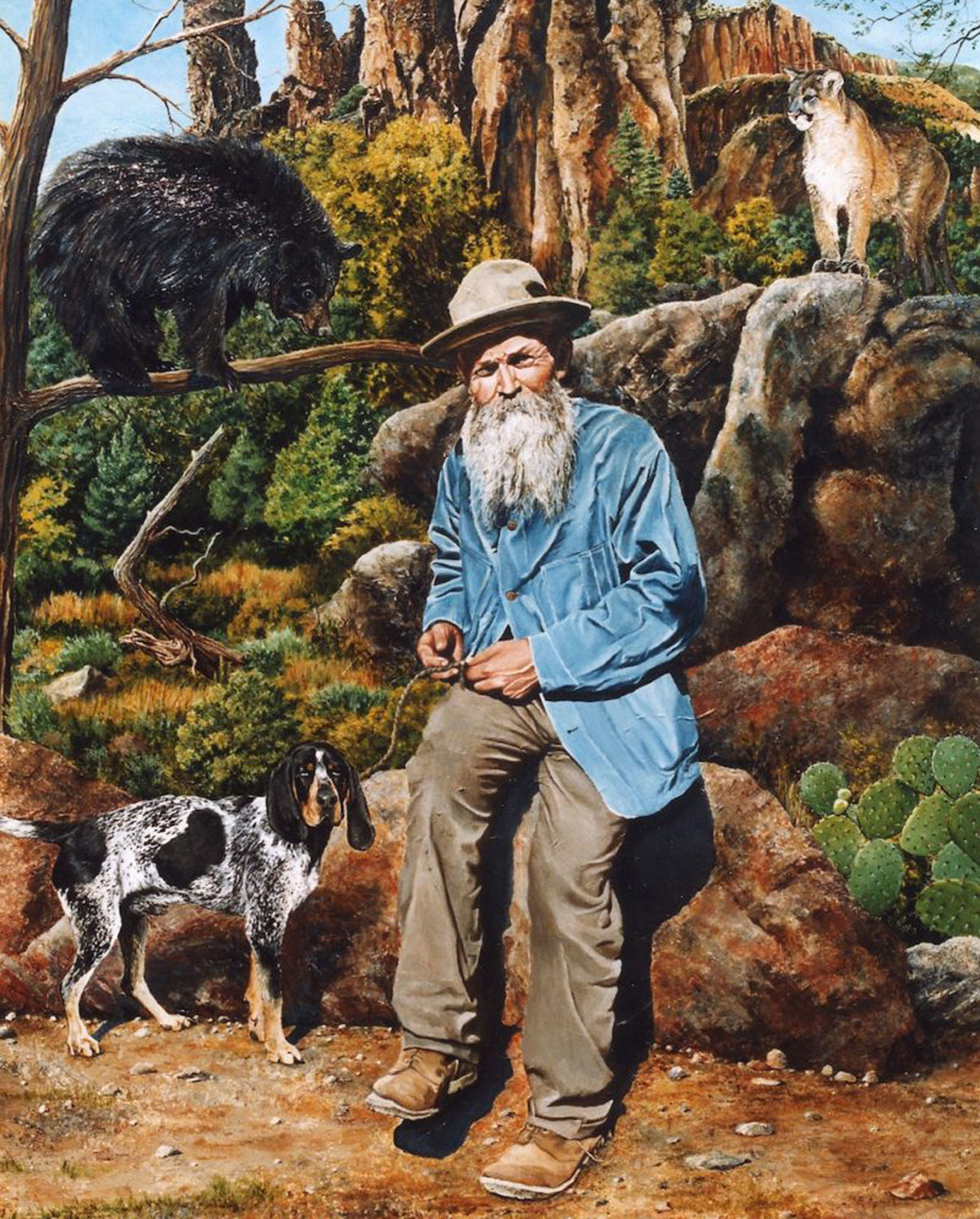

This portrait, entitled Ben Lilly, Mountain Man, was painted by Lois Duffey of Silver City, New Mexico. The original hangs in Dexter Town Hall in Dexter, New Mexico. Image courtesy of Lois Duffey.

Lilly’s reputation as a bear and lion hunter spread and, in 1907, he was asked to serve as one of the guides on President Theodore Roosevelt’s second black bear hunting expedition in the Deep South. The hunt took place in Tensas Bayou in northeastern Louisiana. Roosevelt was the guest of businessman John M. Parker, who later became governor of Louisiana, and John A. McIlhenny of Avery Island and Tabasco Sauce fame, a former Rough Rider who had fought with Roosevelt in Cuba.

Notably, McIlhenny’s brother, Edward A. McIlhenny, was the man who later edited the writings of famed turkey hunter Charles L. Jordan and, in 1914, produced the first book ever devoted to turkey hunting, The Wild Turkey and Its Hunting, which today is a much coveted classic. For more information about Jordan and McIlhenny, see Jim Casada’s outstanding book, Remembering the Turkey Hunting Greats.

After Roosevelt’s somewhat lackluster bear hunt in Mississippi in 1902, he was anxious to return to the South and try again. The ’02 hunt had garnered a great deal of publicity for the president, labeling him with the undesired nickname of “Teddy.” Three days of hunting had failed to produce a single bear, so to remedy this embarrassing situation, the guides tracked down a feeble old bear on its last leg. They tied the poor creature to a tree and summoned the president. Roosevelt took one look at the bear and refused to shoot it, aptly claiming it would be unsporting to do so.

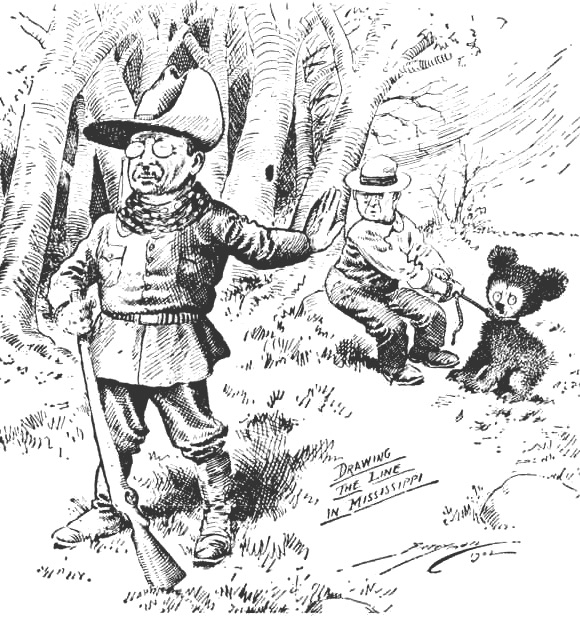

Teddy” Roosevelt cartoon by Clifford Berryman titled Drawing the Line in Mississippi.

The old bruin was put out of its misery, and the story made national headlines. Somehow in translation, the bear Roosevelt refused to shoot became a helpless young cub. A cartoonist drew a cartoon of the president refusing to shoot the bear and a candy store owner in Brooklyn, New York, saw a chance to capitalize on the situation by displaying two small handmade bear cub stuffed animals in his store window. He labeled them “Teddy’s bears.” The nickname “Teddy” caught the country by storm. From that day forward, the “huntingest” president in history would be fondly known as Teddy, although he never condoned it.