Two hours after leaving camp we came across the fresh trail of a small herd of perhaps 10 or 15 elephant cows and calves, but including two big herd bulls.

At once we took up the trail. Cuninghame and his bush people consulted again and again, scanning every track and mark with minute attention. The sign showed that the elephants had fed in the shambas early in the night, had then returned to the mountain, and stood in one place resting for several hours, and had left this sleeping ground some time before we reached it.

After we had followed the trail a short while we made the experiment of trying to force our own way through the jungle, so as to get the wind more favorable, but our progress was too slow and noisy, and we returned to the path the elephants had beaten. Then the ’Ndorobo went ahead, traveling noiselessly and at speed.

One of them was clad in a white blanket, and another in a red one, which were conspicuous, but they were too silent and cautious to let the beasts see them and could tell exactly where they were and what they were doing by the sounds. When these trackers waited for us they would appear before us like ghosts. Once one of them dropped down from the branches above, having climbed a tree with monkey-like agility to get a glimpse of the great game.

At last we could hear the elephants, and under Cuninghame’s lead, we walked more cautiously than ever. The wind was right, and the trail of one elephant led close alongside that of the rest of the herd, and parallel thereto. It was about noon. The elephants moved slowly, and we listened to the boughs crack, and now and then to the curious rumblings of the great beasts. Carefully, every sense on the alert, we kept pace with them. My double barrel was in my hands, and whenever possible, as I followed the trail, I stepped in the huge footprints of the elephant, for where such a weight had pressed there were no sticks left to crack under my feet.

It made our veins thrill thus for half an hour to creep stealthily along, but a few rods from the herd, never able to see it, because of the extreme denseness of the cover, but always hearing first one and then another of its members, and always trying to guess what each one might do, and keeping ceaselessly ready for whatever might befall. A flock of hornbills flew up with noisy clamor, but the elephants did not heed them.

It made our veins thrill thus for half an hour to creep stealthily along, but a few rods from the herd, never able to see it, because of the extreme denseness of the cover, but always hearing first one and then another of its members, and always trying to guess what each one might do, and keeping ceaselessly ready for whatever might befall. A flock of hornbills flew up with noisy clamor, but the elephants did not heed them.

At last we came in sight of the mighty game. The trail took a twist to one side, and there, 30 yards in front of us, we made out part of the gray and massive head of an elephant resting his tusks on the branches of a young tree. A couple minutes passed before, by careful scrutiny, we were able to tell whether the animal was a cow or a bull, and whether, if a bull, it carried heavy enough tusks. Then we saw that it was a big bull with good ivory.

It turned its head in my direction and I saw its eye, and I fired a little to one side of the eye at a spot which I thought would lead to the brain. I struck exactly where I aimed, but the head of an elephant is enormous and the brain small, and the bullet missed it. However, the shock momentarily stunned the beast. He stumbled forward, half falling, and as he recovered I fired with the second barrel, again aiming for the brain. This time the bullet sped true, and as I lowered the rifle from my shoulder, I saw the great lord of the forest come crashing to the ground.

But at that very instant, before there was a moment’s time in which to reload, the thick bushes parted immediately on my left front, and through them surged the vast bulk of a charging bull elephant, the matted mass of tough creepers snapping like packthread before his rush. He was so close that he could have touched me with his trunk.

I leaped to one side and dodged behind a tree trunk, opening the rifle, throwing out the empty shells and slipping in two cartridges. Meanwhile Cuninghame fired right and left, at the same time throwing himself into the bushes on the other side. Both his bullets went home, and the bull stopped short in his charge, wheeled, and immediately disappeared in the thick cover. We ran forward, but the forest had closed upon his wake. We heard him trumpet shrilly, and then all sounds ceased.

The ’Ndorobo, who had quite properly disappeared when the second bull charged, now went forward and soon returned with the report that he had fled at speed, but was evidently hard hit, as there was much blood on the spoor. If we had been only after ivory we should have followed him at once, but there was no telling how long a chase he might lead us, and as we desired to save the skin of the dead elephant entire, there was no time whatever to spare. It is a formidable task, occupying many days, to preserve an elephant for mounting in a museum, and if the skin is to be properly saved, it must be taken off without an hour’s unnecessary delay.

So back we turned to where the dead tusker lay, and I felt proud indeed as I stood by the immense bulk of the slain monster and put my hand on the ivory. The tusks weighed 130 pounds the pair.

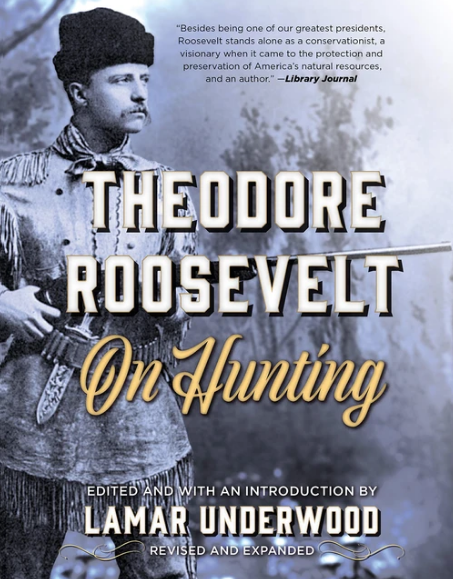

There have been few hunters as daring, as powerful, and as articulate as our twenty-sixth president, Theodore Roosevelt. From his ranching years in the Dakota Territory to the famous African adventures, Roosevelt’s tales are unparalleled stories of the hunt. The best of them are collected here.

There have been few hunters as daring, as powerful, and as articulate as our twenty-sixth president, Theodore Roosevelt. From his ranching years in the Dakota Territory to the famous African adventures, Roosevelt’s tales are unparalleled stories of the hunt. The best of them are collected here.

Of Roosevelt’s many volumes of hunting and exploration, two reader favorites have always been Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail and African Game Trails, both excerpted here. During his ranching years, Roosevelt ranged far and wide, and his African trips were also famously bold. In all his expeditions, Roosevelt reveals in detail hunts that were incredible journeys of both pursuit and discovery, for wherever he went in the outdoors he assumed the dual roles of hunter and naturalist. Buy Now