The bear pounced on him like a dog on a gopher and was soon shaking and mauling both Earl and the canvas.

Some of the best hunting in North America is to be found south of the Mexican border along the Sierra Madre Mountains, from western Chihuahua and extending down to Tepic. It’s full of big game, including some king-size grizzlies. They average larger than our Rocky Mountain bears. In fact, they resemble our old California grizzly, which was reported to have weighed as much as 1,100 pounds.

Some of the best hunting in North America is to be found south of the Mexican border along the Sierra Madre Mountains, from western Chihuahua and extending down to Tepic. It’s full of big game, including some king-size grizzlies. They average larger than our Rocky Mountain bears. In fact, they resemble our old California grizzly, which was reported to have weighed as much as 1,100 pounds.

Earl Boyles and I had a clash with these Mexican grizzlies in 1913 that I still remember as clearly as if it happened last season. We hired a guide named Sow and arranged for a hunt in the wild and rugged country west of Tepehuanes. A branch railway runs to this little mining town from Durango. We were told that this part of the country was infested with bandits, which local officials admitted, and as the government refused to give us any protection, our guide Sow reluctantly refused to go.

We were cussing our hard luck in the lobby of the hotel in Durango when a stately looking Spaniard came in and Registered. I saw Soto perk up. He recognized the man and went over and talked to him. Soon the two went into the dining room, and when they reappeared half an hour later Soto’s face had lost its gloom.

He introduced the man as Mr. Garcia, who said immediately, “My friend Mr. Soto tells me you gentlemen want to hunt. Bears are killing many of my cattle and I will furnish you horses from my remuda and supplies from my commissary to hunt on my ranch for as long as you can stay.” He admitted there were bandits, but said they worked mostly along the San Bias trail and on north. We’d hunt south of the trail, and besides, Garcia said he kept on good terms with the outlaws by giving them beef and tobacco — a sort of combined tribute and charity.

“Are there many bears?” we asked. “Too many!” he said. He went on to explain that Soto had been his foreman for seven years and knew where the bears ranged. Garcia said he was taking out a 12-mule packtrain next morning.

“You mean there are no roads!” I asked. Garcia shook his head sadly.

“Only trails.”

The hotel manager helped us get off next morning, and made it a point to warn us abut the bandits: We should never trust any of them. If they got the drop on us, they would kill us for our guns and whatever other valuables and money we had.

It took us three days’ packing over rough, scenic country to reach the Garcia rancho. There was a large adobe hacienda surrounded by a high rock-and-adobe wall. Walls four feet thick protected the servants’ quarters and huge supply buildings. The ponderous doors were locked with huge keys which reminded me of an ancient castle. The place was a fortress.

Bright and early next morning Garcia showed us a cow that had been killed by a grizzly. As we approached the kill a black bear raised up from behind the carcass. Garcia cried out, “Get him! He is kill cow!”

Soto was about to shoot when I stopped him. “That little bear didn’t kill that cow,” I said, “and if you kill him he may disturb all the sign around the carcass. We’re after a much bigger bear than that. “The old rancher was disappointed, thinking we’d pardoned a grizzly, but we went on up and found the tracks of a much larger bear, the grizzly that evidently had killed the cow. We showed Garcia the difference between grizzly and black bear tracks and assured him he had made no mistake when he reported a grizzly had done the killing.

He showed us three old-style beartraps built of logs. One had been tom apart and the logs scattered. Garcia said a foreman had found a grizzly in the trap and had made the mistake of shooting him inexpertly with a .30/30 rifle. The wounded bear tore through the logs as if they had been matchsticks. Later they found the foreman dead; the grizzly was gone, leaving a blood trail. That had happened seven months before and there had been no traps set since. Nor any grizzlies killed, for that matter.

In two days’ riding we saw lots of tracks and several kills but no bears. Garcia admitted that only a few kills had been made near the ranch house, and Soto agreed that most of the bears were on the southern end of the place — which was 30 or 40 miles away.

It’s always been my policy, when after any kind of big game, to go where they are the thicket and if necessary live there for a while. So I had Soto bring in four pack burros and outfit them for a trip south.

We got started about 10 am and began to see game almost immediately. We’d gone perhaps 10 miles through some of the finest country to be found anywhere when 30 or 40 wild turkeys trotted across the trail and stopped in a clearing not more than 60 yards ahead of us. Earl took his rifle from its scabbard and dismounted. The turkeys were so innocent of men they didn’t even run when Earl walked toward them. A white gobbler stepped out of the bushes and stretched his longneck, and Earl shot him. Between Monterrey and Tampico I have seen whole flocks of wild white turkeys, but in the Sierra Madre we seldom see more than one or two whites in a hundred.

Soto tied the turkey on one of the pack saddles and we went on. Topping a little ridge, we came to a forest of giant oaks with gray and golden squirrels everywhere and large acorns plentiful. It was typical bear country. A little farther on, we flushed a herd of whitetail deer with their stern flags flying the up-go and down-stop signals. Then several more flocks of wild turkeys. We also saw grizzly sign and all sorts of cat tracks.

This oak forest extended for miles and ended in a beautiful green meadow with a brook running through it. Earl remarked he’d seen a lot of hunting country but this was the nearest to paradise he could remember.

Soto called a halt here, saying we could easily reach the site he’d planned for our permanent camp at Cavernas de Agua (Water Caves), which was at the extreme southern end of the range of mountains we were following. He made a fire and put the pot on while Earl and I unpacked the burros and unsaddled our horses, hobbling all the animals and putting bells on them. The bells weren’t so much to enable us to find our stock in the morning a to keep the cougars, grizzlies, jaguars and wolves from killing it.

By the time we got camp in shape and unrolled our sleeping bags, Soto had the turkey in the large Dutch oven and biscuits in the smaller one. Cooked to a turn with just the right amount of chili to give it zest, that turkey was really something to satisfy the inner man.

As night came on, we lay among the oak leave or on our bed rolls smoking and dozing in the flickering light of the fire. It was hardly dark before the wildlife began calling deep in the west fork of the antiago River not far away. Two jaguars began their peculiar cough like talk, ending with coarse, vicious growl. Wolves howled their lonely plaint, and a little later some owls flitted in through the firelight as if to see what manner of creatures had invaded their domain.

We rolled into our beds and I was soon asleep, though none of us had forgotten the outlaws. Earl seemed especially nervous. We all slept with our side arms on.

The last thing I remembered was the faint tickle of the bells on our saddle and pack animals. Next thing I knew a roar was echoing in my ears and the ground was vibrating around me as if from a small earthquake. When I finally got free of my bedding, I found the horses and burros milling around the camp, apparently having been badly frightened by some beast. It was remarkable that none of us had been stepped on. Whatever caused the panic wasn’t to be seen. It probably lost its nerve before all that human scent as it approached the campfire. But within a few minutes the animals calmed down and started working their way back into the timber. We went to sleep again.

It was daylight when I awoke. Earl and Soto were still asleep, and Soto had his head covered and his bare feet sticking out. I tickled his feet, or tried to, but the naked soles of those feet were about half an inch thick and nothing short of a branding iron would have had any effect. But when I uncovered his head he came to life pronto. He’d gone to bed fully dressed, six-shooter and all.

He went to the creek to wash his hands and face while I placed some dry leaves and twigs on the oak-wood coals that were still alive. We soon finished breakfast and were on our way.

Arriving at the caves about 2 p. m., we found ourselves on the edge of a small version of the Grand Canyon. Five tributaries of the Santiago River converged in the distance. There was water in the cave nearest us, and a spring flowed only a few feet from its mouth. Sow said it was the only water for some miles, and that’s why he proposed we camp there.

Arriving at the caves about 2 p. m., we found ourselves on the edge of a small version of the Grand Canyon. Five tributaries of the Santiago River converged in the distance. There was water in the cave nearest us, and a spring flowed only a few feet from its mouth. Sow said it was the only water for some miles, and that’s why he proposed we camp there.

I took a good look at the animal tracks around the spring at the cave’s mouth and chose a campsite about 50 yards back from the water. There werewolf, jaguar, lion, lynx, deer and turkey tracks around the water, and some of the largest grizzly tracks I’ve ever seen anywhere. For the next day or two we never went near that spring at night, and when we went for water during the day we could expect to see almost anything from wild turkey to grizzly.

Camp was under a big, spreading live oak tree. While we were setting up, a pike whitetail deer came in for a drink and we had camp meat. Soto dressed out the deer and hung the carcass about eight feet off the ground on a limb of the oak beside our bed. I should have known better than to permit that. Soto himself was rarely so careless, but he had decided there was so much game in this area the big meat-eaters wouldn’t bother raiding our camp meat.

We spread our sleeping bag across a 14-foot, 18-ounce tarp, folding seven feet of the tarp back over the bags. That made a bed that would stay dry in rain or snow.

We were many miles from the normal range of bandits, yet we didn’t relax our guard. It may have been fear of bandits that got us in trouble that night.

There was pretty moonlight, and I lay awake for a long time listening to the wild animals. I could hear fighting going on and once the bells of the stock tinkled. Then some of our animals wandered through camp between the spring and our beds. I never suspected they were in trouble.

Finally I dropped off to sleep, and awoke sometime later to hear the thudding sound a boxer makes punching a heavy bag. I screwed my head around cautiously. A huge bear was clawing and slugging the deer swinging from the tree be ide us. The venison would be easy to replace, so I had no intention of disturbing the bear at such dangerously close quarters. Deciding we wouldn’t be bothered if we acted cautiously, I nudged Earl.

I nudged him twice before he moved, but it didn’t occur to me to speak a warning. I should have, because Earl awoke with bandits in mind. Before I knew what he was about, he raised upon his elbow, drew his .45 revolver and shot at the erect silhouette of the bear. I had a feeling right then our goose was cooked.

The grizzly jumped and made a sound like a man’s “Oh! ” at the impact of the bullet. He probably thought a bee had stung him, but Earl, only half awake, fired again quickly. At the second shot the bear looked our way.

I’d already crawled from under the covers with my rifle, and from a kneeling position I fired at the huge bulk as it came hurtling toward us. The shock of the 8 mm. rifle bullet stopped him momentarily. I saw that Earl was hopelessly tangled in his bedding and I yelled, “Roll up in the canvas!” He did, and that’s what saved him.

The bear pounced on him like a dog on a gopher and was soon shaking and mauling both Earl and the canvas. I placed the muzzle of the rifle against the bear’s shoulder and fired. The bullet penetrated both shoulders, rendering the great forearms useless. The first shot had torn away the upper part of the heart.

The grizzly fell on his side on top of Earl (who no longer struggled) roaring and growling with rage and trying over to fasten his teeth in whatever was under the canvas. When the grizzly’s struggle finally stopped, I became aware of Soto standing a little away from me with his six-shooter in hand trembling like a leaf.

Together we rolled the bear off Earl, whom we found alive and miraculously without any broken bones. For that matter, he had no open wounds. His hurts didn’t show till morning, but the bedding was so badly soaked with bear blood sleeping in it was impossible. We made a fire between the campsite and the spring and sat up for the rest of the night. By daylight Earl could hardly move. There was scarcely a place on his body that wasn’t bruised black and blue.

We couldn’t find the deer carcass that morning. Some animal had evidently come in boldly after we retreated to our new site and carried away the carcass of the deer while we sat by the fire. The only tracks we found other than grizzly prints were of a very large cat.

Then we tackled the grizzly carcass. Sow and I had managed to get it off Earl during the night, but we couldn’t budge it off our bed. It was cold and stiff now and the legs stuck out like bedposts. We had to saddle two horses and drag the carcass out of camp with lariat ropes.

At noon, only three burros came in for water and I thought immediately of the tinkling bells I’d heard during the night. Backtracking the stock, we found what had taken place. As a rule burros don’t help each other, as many animals do, but they are terrible fighters when cornered. Ours had fought a pack of wolves. There’d been a lot of blood spilled and the wolves had killed, eaten, or dragged away most of our pack animals. We found one dead wolf and a crippled one that we killed.

While Earl convalesced, we killed another deer and hung it in a tree well out of camp. The next morning it, too, was gone. We trailed and killed the raider this time — a large jaguar.

It was several days before Earl could walk or ride, and, in the meantime, Soto showed me the country. There were no kills around the spring but within half a mile of there we found many old kills and some fresh bone. Then he took me southeast nearly a mile from camp to where a steep, narrow trail came up out of the great canyon basin. In some place this trail was so narrow a critter would have had difficulty turning around. If a large animal slipped here it would roll for at least 50 yards. There were bleached bones all over the steep sidehill, as well as some fresh ones. I knew the explanation. We’d had a similar set-up on the west lopes of San Francisco Peaks, just a few miles north of Flagstaff, Arizona. A grizzly there would ambush cattle on the narrow trail and knock them over a deadly drop-off.

“Do these bears do this in daylight?” I asked Soto. He thought they did, but mostly in the evening or early morning.”

The trail was crooked and a little brushy point jutted out less than 50 yards from where most of the killing had been done. There was still another place farther down that was completely hidden from our view. It was getting late now, and the trail was in shadow. The upper side was just gloomy enough to hide a bear and the wind was right for us also. I saw trees and brush enough to conceal half a dozen grizzlies. Far down the trail we could see a small herd of cattle slowly working their way up to water. They were so far away, I had my doubts they would reach us while it was still light enough to shoot, but we decided to wait anyway.

Earl, back at camp, had said he was going out with his .30/30 rifle and a .22 to try for a deer and young turkey at the spring. Even now Soto and I heard turkeys somewhere above the trail. I got out my wing-bone call and began making turkey talk. They answered and came down on the trail. When they failed to locate the calling turkey, they went on up the trail where we knew Earl would be waiting. We figured that if the turkeys had been unable to locate us, no bear ever could.

The turkeys had only been gone for a few minutes when Earl’s .30/30 rifle sounded in the distance. But that wouldn’t alarm either the turkeys or a bear for long. Shooting in a country seldom hunted, where thunder showers are frequent, disturb game little. Soto and I had just made cigarettes when we heard a slight sound in the bushes above the trail and saw the scrub oak bushes move. No sooner had we ground out our cigarettes than around the curve came a long-horned, spotted steer and three cows. This wasn’t the same bunch we’d seen below. These apparently had been on one of the many invisible curves in the trail, and much nearer us.

Just then the lead steer snorted and sprang forward as a grizzly jumped out of the brush and with one smashing blow broke the second animal down in the hindquarters. The last cow reared on her hind legs, spun around like a top and ran. The second cow was lower in turning and the bear raised up on his hind legs to land a steak maker. We both shot at that instant. One bullet took effect in the bear’s left shoulder, and his cow-killing blow never landed. The cow completed her turn and ran.

The old grizzly roared and wheeled about, looking for his enemy, but finally lost his balance and rolled down the rocky slope to join the crippled cow below. He was dead when we got to him. We shot the maimed cow.

In the ensuing days we killed seven more bears in the vicinity. Earl still carried bruises from his mauling when he got back to Durango. It was the first and last time he ever picked a fight with a grizzly with only a .45 revolver to defend himself. It’s dangerous to dream of bandits when there are grizzlies about.

In the ensuing days we killed seven more bears in the vicinity. Earl still carried bruises from his mauling when he got back to Durango. It was the first and last time he ever picked a fight with a grizzly with only a .45 revolver to defend himself. It’s dangerous to dream of bandits when there are grizzlies about.

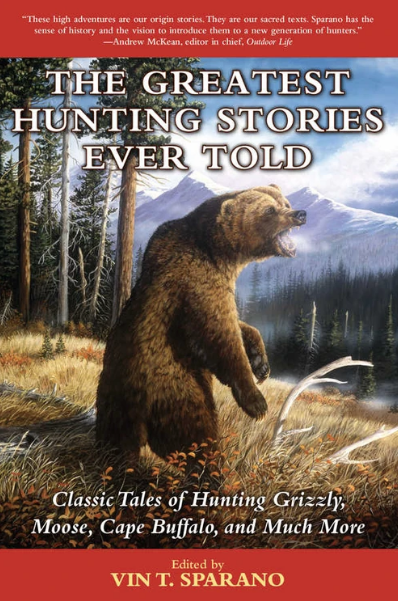

Elephant. Bear. Moose. Rhinoceros. Buffalo. Lion. Since prehistoric times man has hunted. An elemental part of life, seeking out and overpowering large, strong, and fast animals has been a pivotal part of human evolution.

Elephant. Bear. Moose. Rhinoceros. Buffalo. Lion. Since prehistoric times man has hunted. An elemental part of life, seeking out and overpowering large, strong, and fast animals has been a pivotal part of human evolution.

In later times, when hunting for food wasn’t necessary, man still tracked down his prey. Following an instinct for adventure, for the thrill of defeating formidable opponents, man hunted.

Now, for the forty million Americans who hunt, here is the perfect companion. The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game. Buy Now