Your chances will be fewer, but traditional spot-and-stalk bear hunting on horseback enables you to see more of the countryside and its wildlife.

There’s nothing quite like the romance and tradition of hunting from horseback. Rather than concentrating on where you need to put each foot, traditional bear hunting gives you the chance to truly observe the scenery and topography of the country you’re in. That’s especially important when hunting through the astounding scenery of Idaho’s Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness. The largest contiguous designated wilderness in the United States (outside of Alaska), the area encompasses more than 2.3 million acres of pristine habitat.

I had long wanted to visit the U.S. and hunt black bears there. It’s not for the faint of heart, for not only is the terrain steep and treacherous—frequently too steep for the sure-footed steeds we were using—you are also completely out of touch with the outside world. A digital detox of the best possible sort.

I had long wanted to visit the U.S. and hunt black bears there. It’s not for the faint of heart, for not only is the terrain steep and treacherous—frequently too steep for the sure-footed steeds we were using—you are also completely out of touch with the outside world. A digital detox of the best possible sort.

The black bear is not as ferocious as the grizzly or brown bear, and in this area they’re smaller than in other regions; a full-grown male reaching only five feet or so. These black bears are also known to defy their own name. Around 20 to 25 percent are not black, but range in color from pale to sandy brown to the deepest auburn.

As Adam Beaupre, my guide and owner of Horse Creek Outfitters, explained, “If you see one that’s three hundred pounds and six feet, it’s big for us.”

Given that we were hunting in the spring when the bears had just emerged from hibernation, Adam told me they were likely to be even lighter than usual.

High-quality rifles and optics were essential for pinpointing the distances the hunters would have to shoot.

“They’ve burned off all their fat, so they’ll be slimmer than later in the year when they’ve made up the weight. They don’t tend to go too far in the spring, and often a bear will work the same 200-yard area for insects and vegetation. They do scavenge, but only around ten percent of their diet is meat. Their paws will still be tender, and they need to build up their strength.”

We’d used horses and pack mules to carry our supplies and us in for the week to our camp on Horse Creek. Adam has a herd of around 26 quarter/draught-cross horses, which range from 15 to 17 hands high, though he generally prefers mules.

“They’re lower maintenance and smarter. It does mean that if you’ve got a bad one, it’s smart and bad—a tough combination—but they’re generally easier than the horses.”

The other advantage of traveling on horseback is that you see more wildlife and disturb fewer animals, though Adam says the method is being used less frequently than in the past.

“Hunters often hike in these days, carrying their packs or use backcountry dirt bikes. I’m not too keen on those.”

One can see why given the disturbance that must cause. But despite entering the area on horses, setting up camp pushed any bears away from our direct surroundings, so we had to climb up the sides of Horse Creek canyon to reach better vantage points. Working the canyon meant that any shot was likely to be at relatively long range, between 200 and 500 yards.

It certainly puts into perspective one of the differences between European and American hunters, for while many sportsmen from the U.S. practice and are comfortable shooting at longer distances, in Europe we tend to shoot at far shorter ranges. Interestingly, the reverse is true of running game, and many American hunters are unfamiliar with the idea of shooting driven boar and other mammals.

For longer-range shots, there are a few essentials: be practiced and competent at a variety of distances, carry trusted and quality equipment, and have plenty of experience.

Given we were using the spot-and-stalk method rather than sitting in a treestand and baiting bears, our chances would be fewer, but the hunt would be just as I’d always imagined for my first bear. We’d see more of the challenging terrain, as well as the rich and diverse wildlife, which, for an out-of-towner like me, is just as important.

Sure enough, as the week wore on, we were lucky enough to see bighorn sheep, mule deer, elk and mountain goats, all of which took little notice of us when we were on horseback in search of bears. The bruins, however, were proving elusive.

After a day on horseback, the guides and hunters set up their camp next to Horse Creek in Idaho’s Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness. A look at the map revealed the steepness of the terrain.

The nature of the topography meant that we often had to leave the horses at camp, setting off on foot and covering miles of the steep ground each day to spy the opposite side of the canyon—some of the hardest hunting I’ve ever experienced internationally, bar none.

I can’t remember the last time I’ve been properly frightened. The fear didn’t come from bears but from the perceived physical danger I had put myself into. Scrambling across rock faces with sheer drops or using slippery fallen trees as bridges to cross ice-cold meltwater rivers quickened my pulse daily. It was managed risk for the guides; crossing a road in a city is a higher risk for them. But for me, being in an unfamiliar environment gives me perspective on how risk-free my day-to-day life is away from the wilderness.

Risk and, ultimately, fear put me directly in the moment and rebooted my mind. That feeling is one of the main reasons I like to hunt in the wilderness, and my Idaho hunt more than satisfied that lobe of my brain. It was my mental version of control, alt, delete.

By the fifth day in camp, we’d come close to a shot twice but hadn’t managed to close the gap quite enough. As Adam was guiding fellow hunter Jeff Johnston and me up a particularly difficult rocky outcrop, I made the mistake of looking down. I froze, paralyzed and suddenly acutely aware of my mortality. It took all my mental and physical strength to move on, with Adam’s helpful grip pulling me up to the next ledge. With adrenaline coursing, I pushed on up another step and another, this time hands and legs working like a dog with four points of contact, until I got to a spot where I could sit. My breathing was ragged and my hands were trembling, but the feeling of being so close to danger was intoxicating.

Adam and Jeff were nimbler than I in this environment, both pushing along the next ridge to spy across the opposite slopes of the canyon while I stayed and took my binoculars to do the same.

I don’t know if it was the adrenaline, because certainly my hands, shaky as they were, didn’t help, but within seconds I spotted a bear. Bright cinnamon, the animal’s pulsating movement reminded me of a caterpillar with his peculiar rolling motion. Backlit by the morning sun, it was silhouetted with a halo of light and looked unmistakably bear-like. I quietly called to Adam to take a look, but by then the animal had once more disappeared into a vein-like undulation and I could not spot it again. Never has high-quality glass been so important; moving inch by inch, then repeating the process, we scoured the hillside.

It took a while, but finally we spotted the bear once more. Now came the hard part: trying to get closer. The bear was some 1,500 yards away, so we needed to close the gap. Not only that, but it was moving at considerable speed. Jeff and Adam set off, stopping to check on its position every few yards but trying to move at a good pace themselves. I stayed in position to keep spotting. I, being cameraman that day, was carrying a pack with 50 pounds of photographic equipment on my back—which didn’t help my balance or progress.

After what seemed like hours of trying to keep up with the bear, Jeff and Adam came to a narrowing of the canyon. Here was their chance.

Looking from one side of the gorge to the other was the daily routine. Gaining elevation made it easier to see more of the landscape and hopefully more bears.

I watched as Jeff found a suitable rest, set up the shot, adjusting for windage and the 300-yard distance thanks to the ballistic calculator in his Geovid rangefinder, and waited for the bear to stop, if only for an instant. It did, and Jeff didn’t hesitate. The rifle boomed out across the canyon, and, watching through my binoculars, I saw the impact. The bear dropped on the spot.

The hard work was hardly over, though. While Idaho doesn’t have a “wanton waste” law for bears (which would make it illegal not to take the meat), we wanted the meat for camp.

This fresh track was surprisingly close to camp.

We made our way down to the base of the canyon where Horse Creek rushed along wide and wild. Luckily, with a guide such as Adam, you know there’s a plan. He knew exactly where to find a strong tree that had fallen to make a natural bridge, which he shimmied across. He then dragged the bear to the tree, trussed it with a strong rope and brought the end of the rope back over to our side so we could haul it across. Once it was on our side, Jeff could admire his bear properly.

Bright cinnamon, the animal was, at Adam’s best reckoning, five years old and a decent size for the area. That night, as we tucked into some hearty camp fodder, Adam told me how he’d ended up in the outfitting business.

“I bought Horse Creek Outfitters six years ago,” he said. “I’d been working in the corporate world and got to a point in life where I realized that I had to do something I was passionate about, so I went on a road trip with my wife, and we found this. There’s no contest!”

I have to admit, I found it hard to picture Adam, a consummate outdoorsman, in a suit juggling figures—but he does say the six years he spent in finance have put him in good stead.

“You really get to see people’s true colors when you are looking after their money! In seriousness, though, you learn to be a good people person and, no matter how good a hunter, horseman or hiker you are, if you aren’t good with people, you won’t be good at outfitting. You’re keeping people safe, as well as managing their emotions and expectations during a trip that can be scary, exciting, disheartening, elating and disappointing.”

Adam is right. Rarely on a hunt, particularly one in which I didn’t succeed, have I felt so many emotions, fear perhaps topping that list. It put into sharp perspective how safely we lead our lives and how rarely we are truly fearful. And fear is a funny thing: it’s visceral, it wakes you up, and it allows you a reset on life. Everything comes into focus. Everything is raw.

All of this is not to say that we were being reckless—I’d describe the trip as highly successful regardless of the fact I failed to shoot a bear myself. It was my fourth attempt at a bear, and I’m still determined that one day I’ll shoot one, but I would prefer not to do so over bait. The challenge, the excitement and the skills needed for a successful spot-and-stalk hunt at these animals is worth the wait.

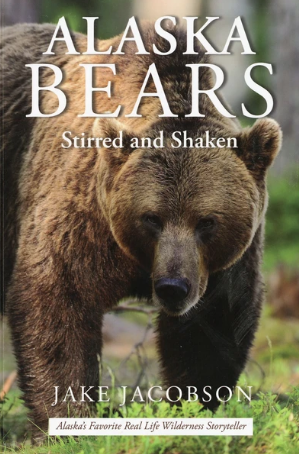

A collection of 24 stories describing Jake Jacobson’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska.

A collection of 24 stories describing Jake Jacobson’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska.

Jake came to Alaska in 1967 and among other things, he holds Alaska Master Guide license #54, a commercial Pilot license, a 100 Ton Mariner’s license, is a Benefactor Life member of the NRA and has operated from his eighty acre private land located 155 miles north of the Arctic Circle since 1969. Shop Now