Suddenly the branch snapped, and once again I experienced that awful sensation of falling. And just as suddenly, I lost consciousness.

As we left the port of Yokohama for bear hunting in Japan, dropped slowly down the bay of Yedo, passed through the Uraga channel and crawled lazily southward on our way to Hiogo, no more efficiently equipped little schooner than the Nimrodor a more jovial and sportsmanlike set of fellows than her crew were to be found in the waters of Japan.

We were bound for the hilly regions of Kioto, where Mr. Bruin has for centuries regarded himself as the principal inhabitant, specially reserving for the use of himself and family certain fastnesses among the rocks, from which he descends to levy such tribute among the vegetable gardens as the season and circumstances may afford.

Japanese coolie, resplendent in his hunting attire.

Brown and the major were old hands with the rifle, and beguiled the time with many wondrous yarns of feats performed and dangers dared in the far West. To these, Mackenzie, an Eastern veteran of mighty deeds among tiger-haunted jungles, replied with hair-raising stories of midnight shrieks and missing coolies, while Fitzgerald and I dropped appreciative or deprecatory remarks as the exigencies of the competition required.

In this agreeable manner, with an occasional snapshot at a passing gull, more for the purpose of getting our shooting eye in than with any idea of actual sport, we sighted and rounded the point of volcanic Oshima, and eventually found ourselves landing upon the wharf at the treaty port of Hiogo.

Our stay here was of brief duration and, having engaged the necessary men to superintend the conveyance of our luggage and act as guides and beaters in the drives, we bade adieu to the courteous consul and set forth.

We had the best carriages that could be procured, but the best, at that time, did not go very far in the matter of ease. They were made of rough-hewn timber, of triangular shape, mounted upon three wheels, each one fashioned from a solid piece of wood and drawn by lethargic bullocks. We had vainly endeavored to procure mounts of a more civilized character. We could have obtained ponies at fancy prices, but never a saddle was there to be had.

Numerous and exciting were the adventures we had on the road. At one time, the major had just turned to converse with Brown when his ox stepped over to the low line of rushes to reach a pool of water, and the major had to leap hastily from the rear of his cart.

Later on, Mackenzie and I were riding side by side, when from some cause unexplained, our wheels became locked, and the animals set off at a fair pace. The sides of our vehicles tilted up in extraordinary fashion, while for some minutes our joint endeavors to pull up proved unavailing. Finally, the conveyance spun around like a top and pitched heels over head into a ditch.

In due course we arrived safely at Kioto, where we were to leave the greater part of our belongings and proceed some 50 miles farther to an outlying village intended as our headquarters. In a few days more, we reached the wild mountainous regions of Omi, where we formed our camp at the dwelling of an isolated goat herder. From here, we dispatched scouts to ascertain the latest movements of Bruin & Co. and report generally upon the prospects of sport.

In the meantime, we were not idle, for the country around us literally teemed with game. We found antelope, deer and wild boar, and made many good bags of mallard, widgeon, woodcock, plover and snipe. When word reached us that traces of bear had been discovered at no great distance into the forest, we felt almost reluctant to leave camp. However, bear shooting was what we had come so far to obtain, and bear shooting we meant to have, in spite of all the other attractions.

We started the following morning, accompanied by some half-score natives and as many dogs of the remarkable fox-like species peculiar to the country.

The weather was delightful: bright sunshine smiling cheerily around us as we pushed our way up a steep gully that led to the haunts of bears in the higher parts of the forest.

At first the pathway was easy and well defined, but gradually the ascent steepened and the track became more obscure. After an hour’s work, a brief halt was called and the supply of saké was passed around. Saké, be it understood, is the national drink of the Japanese, brewed from rice, and the best qualities closely resemble pale sherry in appearance, but by no means equal that wine in other respects.

Upon resuming the ascent of the hillside, we climbed in single file through the luxuriant forest and, about noon, our guides informed us that we had reached the ranges of the bear, and that at any moment we might come across game. We therefore kept rather more on the qui vive, and were presently startled by a loud yell, which suddenly burst from the unfortunate major who occupied the post of honor in the van. Rushing over to him, we were surprised to find him standing bare-headed in the path, gazing upward and furiously gesticulating at a small, but active brown monkey that had seized and made off with his cork helmet.

I am afraid our relief at finding the matter no worse somewhat tempered condolences, but the major was not the man to tamely brook such an insult, and a shot brought the poor little author of the mischievous outrage to the ground. But the killing of the monkey did not restore the helmet, which remained up a tree for a good half-hour, until recovered by one of the natives whose climbing abilities were only second to those of the thief.

Soon after this incident, one of our men announced his discovery of a bear track, and we quickly gathered around the spot for an examination. The Japanese bear, it appears, is a sociable animal that delights in taking his wife and family with him on his various excursions in search of sustenance or diversion. The tracks showed that three full-grown animals, and two of lesser development, had passed that way, and we anticipated a lively day’s sport. Nor were we disappointed.

Carefully we followed the trail, which led in and out among the loose rocks and camphor-wood bushes. The dogs were sent to the rear until we should have need of their services if a bear declined to leave cover.

In a short time, we came upon a small open glade of bright spongy turf, across from a small stream that bubbled and sparkled. Directly in front was the opening of what appeared to be a large cavern. The open space before the cave was a veritable bear garden, in which we saw no less than seven animals—five of them full grown and of the largest size—disporting themselves on the grass or on the margin of the stream.

A hasty glance showed that we were in the wrong place for an attack, as the bears had an open retreat behind them into the cavern. We decided that the major, Mackenzie and Jones should steal ’round to the far side with half-a-dozen beaters and the dogs in order to cut off the retreat, while Fitzgerald and I remained on observation duty and in command of the only other means of escape. The signal for hostilities was to be the branch of a pine tree thrown over an intervening rock to attract the bears’ attention and announce the arrival of the flanking party at the stipulated point.

While these preliminary movements were in progress, Fitzgerald and I had excellent opportunities to observe the animals. There were three full-grown males and two females, along with two cubs from 15 to 18 months old. While the youngsters disported themselves like a couple of ungainly kittens, tossing and tumbling over one another after a stick or a loose stone, the more sedate elders lounged in the shade, occasionally chewing on a few refreshing leaves from the branch of a neighboring tree.

A large branch suddenly falling from overhead among the astonished bears apprised us that our friends were in position. I sprang through the screen of bushes and fired at the largest. To my delight, the first shot brought him down, and at the same moment the major and his party fired a hasty salute. Two large ones and one cub fell to this discharge, but the remaining two adults and the cub made a simultaneous rush at us before we could reload.

The situation was critical, and we promptly took to flight. Fitzgerald sped along the path by which we had come, while I attempted a strategic movement that I hoped would enable me to join my comrades. I clambered up a rock and, hastily reloading, was beginning to think well of my little scheme, when a panting noise and quick breath upon my ear caused me to turn rapidly and find myself face to face with a most active bear. A second brute was a few yards below, and I had only time to discharge my rifle full in the bear’s face and fly for dear life across the rock in the direction of the stream.

Here, to my horror, I ran slap into a third bear, which was toiling painfully up the only road by which I could escape. There seemed nothing for it but a hand-to-hand fight with three infuriated animals, for the beast in whose face I had fired, although severely wounded, was still sufficiently alive to account for me at least.

A Japanese coolie, or porter.

I had already grasped my rifle to use as a club, when I noticed that the branches of a tree that grew across the stream swayed within a yard of my ledge of rock. Looking down, I could see the water running merrily along some 40 feet below. I had no time for hesitation and so, dashing my rifle in the face of the advancing bear, I made a rush and a spring with arms outstretched before me.

Crash! Crash! I went through the branches, and it seemed as if I should never stop falling, when I felt myself strike a projecting limb, which I grabbed and clung to desperately. Suddenly it snapped, and once again I experienced that awful sensation of falling. And just as suddenly, I lost consciousness.

I came to in time to receive the solicitous inquiries of my friends. Fitzgerald, finding himself unpursued, had retraced his flying steps just as the two bears clambered up to the rocky ledge where I had so nearly been trapped. He summoned the others, and an organized siege ensued, which resulted in the extermination of the bears. Then they began their search for me.

We camped the night on the grassy field so lately occupied by our foes, and I was well enough next day to attempt the return trip to Kioto where, in due course I arrived, not much the worse for my adventure.

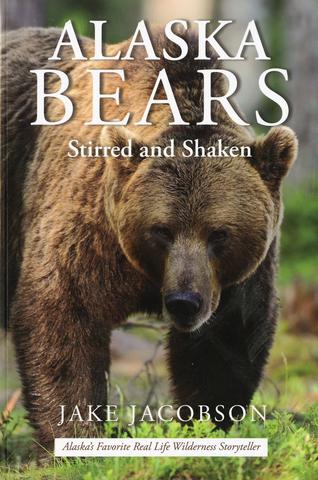

ALASKA BEARS: Stirred and Shaken is a collection of 24 stories describing Jake’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska. Buy Now

ALASKA BEARS: Stirred and Shaken is a collection of 24 stories describing Jake’s personal experience hunting and guiding for all the species of bears in Alaska. Bear biology, hunting techniques, cabin depredations and avoidance thereof, and other aspects of bear pursuits are detailed. These are true stories except for the names of some of the hunting guests from Jake’s fifty years of living and hunting in Alaska. Buy Now