They were among the most peaceable Indians, the papers all said, but they had a grievance. This is the story of the Battle of Sugar Point.

Wild rice. It’s good alright, mighty good, cooked long and slow in moose broth, with maybe morel mushrooms and fine-chipped yellow onions. Stuff it in a mallard, stuff it in a grouse, a goose, even a teal.

How about bone-in, wood-grilled venison chops and cranberry jelly with a bed of wild rice on the side? You might jostle your brother-in-law should he linger too long with a serving spoon, but would you shoot him over his hoggishness? I’ve had brothers-in-laws like that, maybe you did too. But there was a time when men died over wild rice.

Most of the wild rice these days is commercial paddy grown, uniform black grains from California, Wisconsin or Minnesota, but the best is still Indian harvested the old way, a man poling the canoe though the rattling rice, the woman gently bending the canes over the gunnel, rapping them with a stick, while the ripened kernels cascade into a tarp in the boat bottom. The wood-parched product is speckled green, brown and black, even better than the commercial strain, if you even imagine such a thing.

Most Ojibwe live in Minnesota now, but they were originally from Canada where they had early contact with the French Voyageurs. The Ojibwe swapped beaver pelts for knives and muskets and soon became the dominant tribe in the region, pushing south and west, doing battle with the Sioux who were woods Indians in those days.

The Ojibwe were not even Ojibwe back then. They called themselves Anishinabe, “the original human beings” and the Sioux were not Sioux either, but Lakota or Dakota, “Sioux” being an epithet from the French Nadoussioux,“little snakes.” No love lost there.

The Lakota were routed from their fish, moose, deer and wild rice and exiled to the prairie where they domesticated Spanish mustangs and took up buffalo hunting instead. When Lewis and Clark encountered them in 1805, they had only been there three or four generations. And meanwhile, the Ojibwe had trouble holding on to what they had won with French iron and steel.

St. Paul was a brewery and a brothel named for its proprietor, a Frenchman everybody called Pig’s Eye. Just upriver was St. Anthony Falls, waterpower to saw lumber and grind wheat. They called the new town Minneapolis, “water city” in an unlikely conjunction of Lakota and Greek.

Trouble was, spring freshets washed out the machinery and the trickle during fall droughts would scarcely turn it. In 1881, milling interests petitioned the politicians who appropriated funds for two dams upon the Mississippi headwaters to regulate the seasonal flow. The largest of these at Leech Lake in north central Minnesota, was 3,500 feet long and raised Leech Lake water by four feet, drowning out the wild rice beds upon which the Ojibwe depended for sustenance.

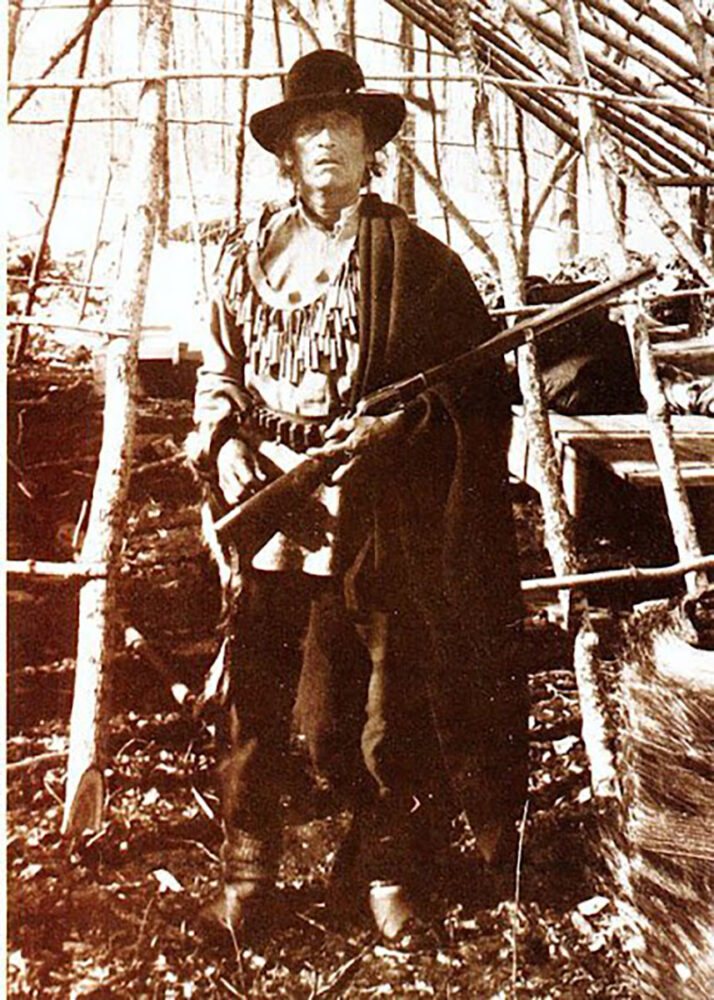

Old Bug

The government men listened intently to the complaints and asked questions. “How many bushels before the dam and how many afterwards? And what was the value of the bushels lost?”

The Ojibwe were stumped. Nobody kept count of the bushels. And mahnomen, “the good berry” was a gift from the Great Spirit. It fed the people and was beyond monetary value. Negotiations stalled and the debt lay unpaid for 90-odd years until the Nixon administration finally anteed up.

Meanwhile, resentment festered until September of 1898 when one Buganegeshig was arrested by U.S. marshals for failure to answer a summons for bootlegging. His name translates “Hole in the Day,” a puzzlement, but most likely his birth coincided with a solar eclipse, of which there were many in the mid-1800s, July 18, 1840, being a most likely candidate. The whites, weary of tongue twisting Ojibwe names, simply called him Old Bug.

The marshals lay a trap, waiting for Old Bug to show up to collect a cash allotment, an annual stipend for some previous land swindle. They had him and another Ojibwe in custody when Bug cried out for help. Fifteen Ojibwe rushed the marshals and freed the captives, and all melted away into the forest. The marshals hot-footed it to the telegraph in nearby Walker and called in the U.S. Army.

The Third U.S. Infantry at Ft. Snelling dispatched 100 men, some fresh back from Cuba, others who had joined too late to get into “the splendid little war.” All were waiting to be mustered out of service. The men boarded an express train, headed north, the first 20 straight to the village where the wardens were overwhelmed. Mostly women and children about, a bad sign if the troops were savvy to Indian ways, which they weren’t.

“Why are you here?” the women asked.

“We are going to hunt ducks,” the lieutenant replied.

The women knew better. They laughed, waggled fingers and tongues. “You come for war,” they said, but they fed the soldiers fish anyway.

The last of the troops arrived in Walker on October 4. A detachment was sent to guard the hated dam lest the Ojibwe blow it up and 80 men embarked upon several small steamers and a barge, crossed Leech Lake in pursuit of Old Bug and the men who had freed him.

St Paul Globe October 7, 1898: Portrait of Melville Wilkinson

Another curiosity: A typical infantry company is 100 men, commanded by a captain, but the detachment included Major Melville C. Wilkinson and Brigadier General John M. Bacon. Why? They were Civil War veterans. Wilkinson was over 60 years old and Bacon was 54, both too old for the Cuban campaign. Wilkinson was decorated for his use of the Gatling gun, mowing down Indians on the plains. He requested a Gatling for use against the Ojibwe. He got it, and also a Hotchkiss rapid fire cannon. Both men were itching for one more fight to crown their careers.

It was a bad idea.

On October 5, the troops landed at Old Bug’s cabin at a place called Sugar Point, a clearing where the Ojibwe had boiled down maple sap for generations. As you might expect, Old Bug was not home. Both the Gatling and the Hotchkiss were too cumbersome for transport by boat and were left behind, as well as tents and rations. Officers carried sidearms and the men Krag–Jørgensen five-shot bolt-action rifles, the Army standard in those days, and each man had 100 rounds of ammunition. General Bacon sent out a reconnaissance detail to search for hostiles, set the other men to digging trenches and rifle pits. The detail came to a creek and didn’t want wet feet, so they returned with news of sighting two Indians armed with deer rifles but running the other way. General Bacon was convinced there would be no fight. Reporters from the St. Paul papers had been allowed to tag along. They found an old war drum in the cabin and began beating it in mockery.

Another bad idea.

What happened next is open to speculation. Bacon ordered no fire unless fired upon. In a war council, the Ojibwe decided the same. But there was a shot, a single shot, and that’s all it took to set-off this wild rice shoot-out. Some say one of the civilians left aboard a steamer took a long poke at two women rounding the point in a canoe. Others say there was an accidental discharge when a pyramid of stacked rifles collapsed. Unbeknown to the soldiers, perhaps 30 Ojibwe had followed the reconnaissance detail back to Sugar Point and lay in heavy cover on three sides of the clearing. Once that first shot was fired, the Ojibwe opened up with their Winchesters.

The effect was immediate and deadly. One private killed on the spot, two more wounded. Major Wilkinson got a nick in one arm, took a bullet though a leg. A medic hauled him to shelter behind the cabin, patched him up. Wilkinson returned to the fight when an Ojibwe swam 200 yards through icy water to take the shot that killed him. “Give ’em hell, boys!” were Wilkinson’s last words. A sergeant attempting to bring word to General Bacon took a bullet in his brain.

The first fusillade lasted 30 minutes and firing continued sporadically until the middle of the afternoon. The troops pinned down, the Ojibwe turned their sights on the steamers. Wooden hulls offered little protection. Several men caught splinters and one pilot lost an arm while everyone groveled in the bilges.

The rattle of the battle was plainly heard in Walker, the crack of the soldiers’ Krags and the boom of the Indian Winchesters. When the firing tapered off, townspeople feared the worst. The telegraph hammered out rumors, a massacre with General Bacon dead. All over the Upper Midwest, the U.S. Army began to mobilize, slow but sure, more Gatling guns loaded onto flatcars, soldiers packed into coaches. The “moccasin telegraph” was busy too. Runners were dispatched to far-flung bands of Ojibwe. Will you join us against the whites?

The troops spent a miserable night in bitter cold, no shelter, no rations. First light, Private Daniel F. Schwallenstocker ventured into Old Bug’s garden to dig potatoes. He was shot dead, by Old Bug’s son some say. Remember his name if you can, he was the last American soldier to die in the Indian Wars.

A relief steamer was dispatched to land supplies and bring off the wounded, but hostile fire drove it away after it got only one man aboard and a single barrel of rations ashore. By afternoon, the firing had ceased and the men were able to make biscuits and bacon, their first meal in two days.

Portraits of six fatalities and wounded US Army casualties displayed in the St Paul Globe October 9, 1898.

The rail line at Walker was finally reinforced on October 7 with 200 more troops from the Third Infantry. Later that same afternoon, Bacon and his men were extracted from Sugar Point by the steamers and barge. The score: Six soldiers and one Indian policeman dead, nine wounded. The Ojibwe had suffered no casualties. Yet in his first report to Washington, Bacon insisted he had won the battle and steadfastly maintained that delusion afterward.

Most Ojibwe wanted no part of the fight, but some did. “[A]s many as leaves in the forest,” one hostile chief bragged. The government tread lightly. Winter was on the wind, the lake would soon freeze and the steamers would be useless. It might take 5,000 men to find and defeat three dozen hostiles and the efforts would surely create more hostility. If those 15 Ojibwe who had assaulted the marshals and freed Old Bug would turn themselves in, there would be no war. General Bacon was furious. He wanted another crack at those Indians. But various chiefs agreed to round them up and send them in, which they did.

A dozen Ojibwe served from two to 10 months but not Old Bug. He returned to his cabin and picked up the soldiers’ empty shell casings, which he fashioned into a necklace which he proudly wore until his death, some 18 years after the shoot-out. He was never arrested, never again subject to any white man’s papers. The government decided to leave him alone.

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself. Featuring both fictional and true-to-life adventures, these astonishing stories are from the creative minds of such legendary authors as Peter Capstick, Archibald Rutledge, Gene Hill, Mike Gaddis, Roger Pinckney and John Madson. Buy Now

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself. Featuring both fictional and true-to-life adventures, these astonishing stories are from the creative minds of such legendary authors as Peter Capstick, Archibald Rutledge, Gene Hill, Mike Gaddis, Roger Pinckney and John Madson. Buy Now