“My work has evolved a great deal in recent years, particularly in the way I apply paint to canvas. I hope that I’ll still be growing at the same rate 10 years from now.”

These words by John Banovich appeared in an article by Editor Chuck Wechsler in the March/April, 1996, issue of Sporting Classics. Though now it’s closer to 27 years, Banovich has taken the kinds of leaps musts dream about. And true to his early aspirations, his work seems to be progressing and rising to levels where the lines between the must, the art and the subject blur beyond capturing a moment on canvas.

These words by John Banovich appeared in an article by Editor Chuck Wechsler in the March/April, 1996, issue of Sporting Classics. Though now it’s closer to 27 years, Banovich has taken the kinds of leaps musts dream about. And true to his early aspirations, his work seems to be progressing and rising to levels where the lines between the must, the art and the subject blur beyond capturing a moment on canvas.

I had the pleasure of working with John on his first book, BEAST, and I came to know a man who believes. A man with passion and humility — a man who does nothing halfway.

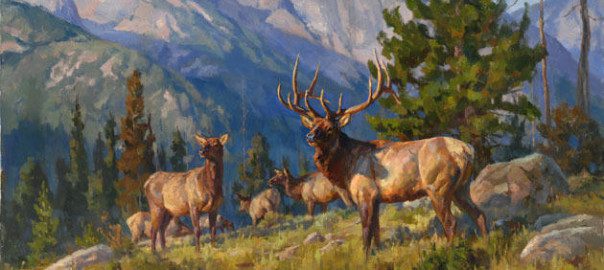

A mesmerizing journey through BEAST allows reader sand art aficionados the chance to experience how John and his work have changed over the years — how each brush stroke reflects his maturity and increased confidence as an artist. His skill at using light and dust and fog to convey mood has always been one of his strengths, but his better understanding and connection to his subjects has elevated his art from a visual experience to one where viewers feel the painting at a more visceral level — as if they are engaged within it.

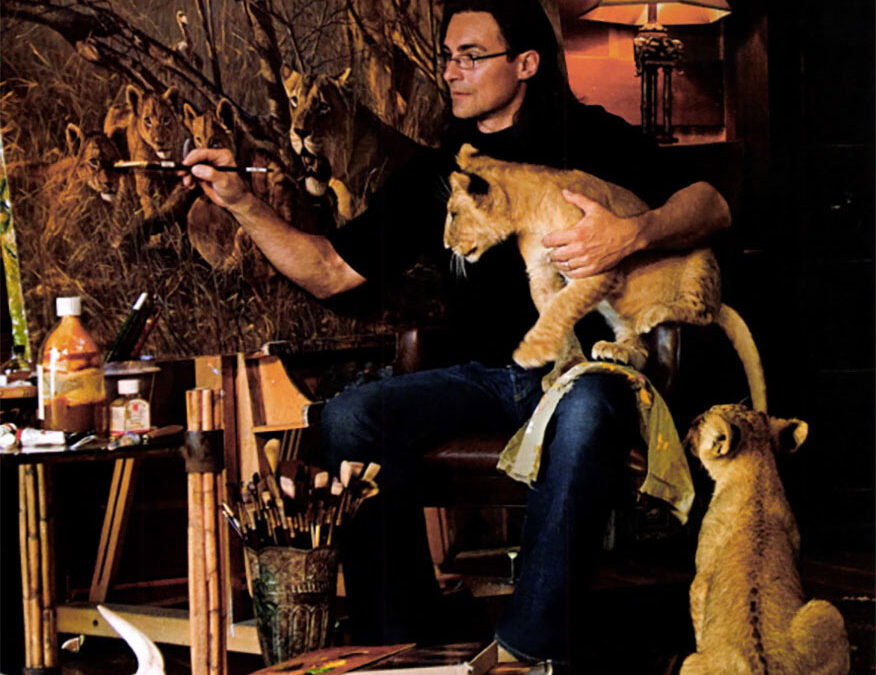

John’s talent and work ethic push the limits of capability because of a devotion that drives him beyond art. He lives what he paints. He tracks lions for research. He digs through the remains of a tiger kill to better understand how it survives. He spends weeks with scientists as they investigate the movements and habits of a snow leopard they may never see. Through this study, he has developed a deep and lasting bond with wild creatures that requires action.

Too Good to Resist

“Though I always considered conservation an important part of my work, I gained insight into the challenges wildlife faces during my research,” John explains. “As I spent time with scientists, conservationists, government officials and hunters, the urgency rang louder and louder in my years. There is a great responsibility in knowing. You just can’t tum away when you know.”

For John, a clear line linking his art and his passion for conservation exists without question. ‘We have been entrusted to be good stewards of God’s precious gifts. Through my work, I want to protect wildlife because it’s the light thing to do.”

John immerses himself in his subject’s world. Although he observes a strict, hands-off approach, he has learned how to interact without being invasive. He wades into their watering holes. He studies the way they stalk prey or behave toward outsiders. And he participates in field research and other conservation programs. All this firsthand knowledge supports his unique talent to uncover what an animal truly is as opposed to what it looks like. A painting like Man Eaters of Tsavo, for instance, reminds you that to hungry lions, anything is fair game.

As these stories unfold before him, he begins to better understand the creatures he paints and the challenges they face in a world where humans consistency spread across traditional habitats. It always leads him to the same conclusion: The people who live with wild animals must be part of the solution. In most cases, the only viable solution includes a plan where local residents actually benefit from the animal’s existence.

Grizzly Encounter

“Wildlife utilization is all some communities have beyond a little cash crop to improve their lives,” John says. “In some regions on earth, saving wildlife means saving people.”

Knowing he had to do more, John started Banovich Wildscapes Foundation (BWF) in 2003. Since then the time, money and effort he devotes to conservation have multiplied. “Today, 20-25% of my work is dedicated to conservation.”

With his unique standing among hunters and non-hunters alike, and his understanding of the people and organizations representing differing interests, John finds success where others often struggle. Conservation organizations, whether hunter-based like Safari Club International or those whose memberships are dominated by non-hunters, often share similar motivations —conserve the world’s wild places for future generations. Why not allow them to coexist in a safe environment?

With BWF, John has created such a place. Part of its mission statement reads, ‘’We foster cooperative efforts to conserve the earth’s wildlife and wild places to benefit the wildlife and the people who live there.”

Palindaba

With the help of sportsmen and other conservationists, John offers solutions that give local people a stake in how their natural resources m-e used. Any successful long-term solution needs that ingredient.

John called BWF’s first major cooperative initiative Kunta Mi — Conserving the Amur Tiger.

One of the most endangered big cats in the world, only an estimated 450 Amur tigers remain in the wild, all of them in the Russian Far East. Only 20% of the tiger’s habitat is protected. Hunting lands comprise the remaining 80%. The responsibility to manage the prey species tigers depend on falls on local hunters.

“As the only people who can legally carry firearms into the forests, these hunters will determine the fate of the Amur tiger. The long-term viability of its survival lies in hunting leases.”

Jumbo

John is part of a cooperative effort to educate Russians on the important role tourist hunters can play. Too often, the only value tigers have relies on ancient Asian beliefs that involve consuming parts to improve virility or cure some other malady. If an alternative means of income linked to the presence of tigers exists, he believes it will go a long way to curb the poaching epidemic.

Along with the Wildlife Conservation Society, BWF has helped these Russian hunters develop a plan that includes trophy hunting as a source of much-needed revenue. They believe that the draw of high-quality trophy potential, a deep wilderness experience, and the chance to stalk game where the earth’s greatest predator lurks will entice many from the international hunting community to “hunt in the shadow of the tiger.”

John believes that once word spreads, hunters will come. “They will come to pursue red stag, roe deer, giant wild boars, Himalayan black bears and sika deer with record potential antlers. In doing so, they can be responsible for saving an animal they will not hunt. If we are successful, the rich hunting tradition of the Russian Far East and the Amur tiger can be preserved alongside one another.”

Big beasts with big teeth. John paints them as if he understands them. Maybe it’s their raw power and his background in bodybuilding. Maybe it’s his favorite childhood story, The Jungle Book, and the challenge of unraveling its most mysterious characters. Maybe it’s how the loyal efforts of a pair of hunting lions affects the heart of a man who once dove into the frigid waters of the Yellowstone River to save his aging Lab. Or maybe it’s something only subconsciously revealed in paintings such as Night Fire and Hyenas in the Distance, which conveys a significantly different side of Africa’s big cats.

Of Three Generations

“Large predators are often keystone species,” he says. “If their numbers are stable or rising, the ecosystem is healthy.”

John began BWF’s Lion P.R.I.D.E. initiative with that philosophy in mind. The acronym stands for Protection, Research, Implementation, Development and Education. Like all of BWF’s initiatives, P.R.I.D.E. finds innovative ways for local people to profit from wildlife — particularly lions. Outside of protected areas, lion numbers are dropping at an alarming rate. Without economic value, big predators are, at best, competition for resources, at worst, man-eaters.

“Local views of predators around the world often develop from the possible negative consequences of that animal’s existence. To combat that perception, wildlife has to have tangible value.”

John believes the best conservation models are mix of both consumptive and non-consumptive methods. Non-consumptive includes eco-tourism — photography and drive-through parks. Consumptive relies on hunting, with tourist, or trophy hunting, the desired form.

“Tourist hunting is the only form of hunting in which success does not rely on the quantity of animals killed.” He adds that it has a smaller impact on an ecosystem and that on a per-participant basis, brings in greater revenue.

“Mark my word, countries with consumptive wildlife utilization as a sustainable management tool will have the last places with intact ecosystems of wildlife on earth.”

Jewel of India

Kunta Mi and P.R.I.D.E are two of John’s major initiatives, but his dedication to wildlife, habitats and other charitable causes knows few boundaries. He works extensively with organizations such as Safari Club International, the Dallas Safari Club, Houston Safari Club Wildlife Conservation Society, the Murulle Foundation, the Craighead Institute and many others. His efforts have raised millions for conservation and humanitarian causes around the globe. He donates paintings for auctions. He donates his time for education and research projects. And through it all, his passion for art and conservation continues to intensify.

You do not see a Banovich painting as much as you feel it. His art pulls you into a place beyond paint and canvas. For anyone who has locked eyes with a wild lion, they know immediately that John saw what they saw, that he felt what they felt, because through his art they can feel it again. Only a handful of wildlife artists have had the ability to create something you cannot turn away from — John does it consistently.

Much has changed for John since Chuck Wechsler wrote about him 27 years ago. He now publishes all his own work. His art is recognized among the greats. His name is consistently mentioned among significant conservationists. He has seen India and Africa and Russia and so many other places the way they really are. He has seen them the way they are meant to be. He has become a man who refuses to settle and is not afraid to take on difficult challenges. He truly understands his belief system and he lives by it.

By following his two passions — wildlife and art — John has made a difference and people are taking notice. His awards include: the “Simon Combes Conservation Artist Award” from Artists for Conservation Foundation; the “Presidential Artistic Achievement Award” from the Society of Animal Artists; the “CJ McElroy Conservation Award” from SCI; and the “Coffee Table Book Award” for BEAST from the National INDIE Book Awards.

Though the awards and recognition are humbling, for John it’s about following a path that chose him as much as he chose it.

“We live in an extraordinary time,” he says. “We can still see megafauna with great freedom. We can still witness natural rhythms as old as time. It would be a shame to preserve that on canvas alone.”

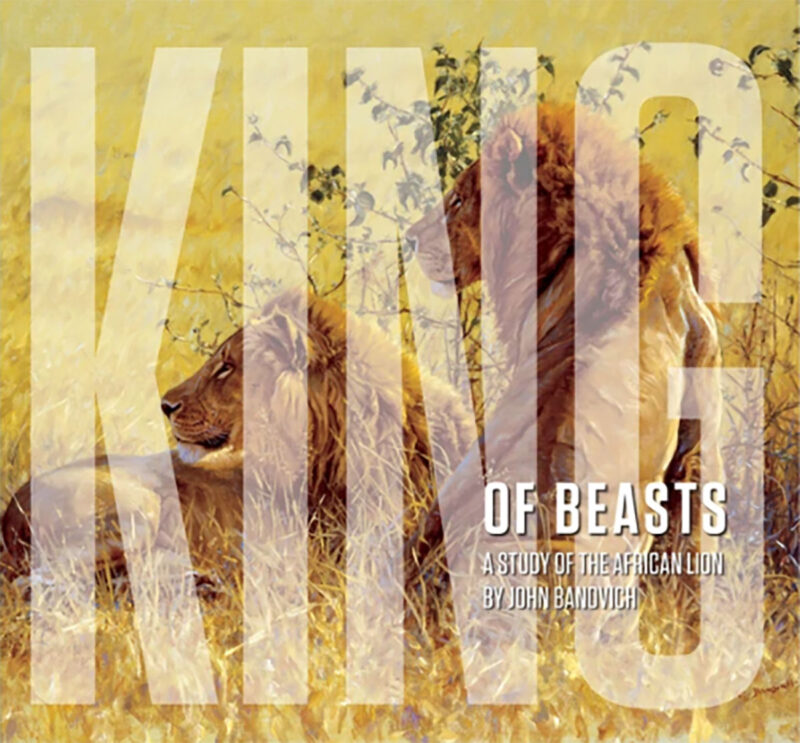

Following best seller and award-winning book “Beast” we are pleased to announce the release of “King of Beasts” by John Banovich. Featuring 208 large format pages, “King of Beasts” illustrates the dramatic artwork of John Banovich, all focused on depicting the extraordinary African Lion. An internationally recognized artist who has studied lions for decades, Banovich has selected a body of work that pays homage and explores questions about mankind’s deep fear, love, and admiration for these creatures. Buy Now

Following best seller and award-winning book “Beast” we are pleased to announce the release of “King of Beasts” by John Banovich. Featuring 208 large format pages, “King of Beasts” illustrates the dramatic artwork of John Banovich, all focused on depicting the extraordinary African Lion. An internationally recognized artist who has studied lions for decades, Banovich has selected a body of work that pays homage and explores questions about mankind’s deep fear, love, and admiration for these creatures. Buy Now