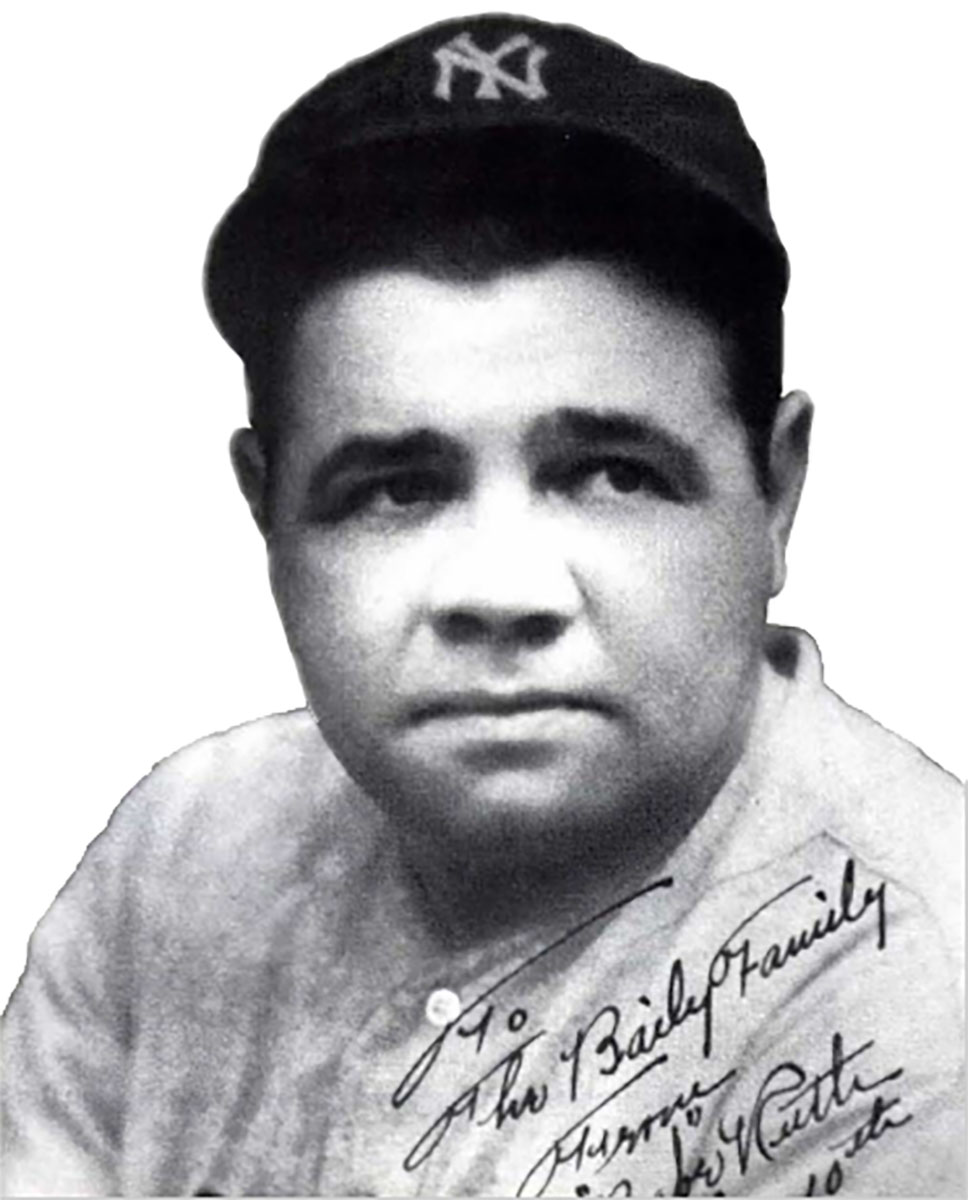

Babe was as close to being a Greek god as this country will ever know, his mythology constructed on the foundations of urban America. Big league baseball was built around big cities, after all, as were the attendant pleasures he so ravenously pursued. Yet, Ruth was also an avid hunter and a fisherman, though his life as an outdoorsman is today not only overshadowed by his uptown escapades, but also seems incongruous in contrast to them.

Babe was as close to being a Greek god as this country will ever know, his mythology constructed on the foundations of urban America. Big league baseball was built around big cities, after all, as were the attendant pleasures he so ravenously pursued. Yet, Ruth was also an avid hunter and a fisherman, though his life as an outdoorsman is today not only overshadowed by his uptown escapades, but also seems incongruous in contrast to them.

Ruth, though, was paradox personified. He rose to stardom from humble beginnings at St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys, a Catholic reformatory in Baltimore. By 1920 his incomparable style and brilliance with the bat had transformed him from an “incorrigible” street kid into America’s golden boy. The public couldn’t get enough, and through the press they followed his every move. One 1927 article on Babe’s hobbies claimed he hunted because he “was born to it.”

But the former urchin from the dockyards of working-class Baltimore was most certainly not born to field sports. While hard to pin down with certainty, Babe probably took up the hunting life in the fall of 1916. At the invitation of a sporting goods manufacturer, Ruth and his first wife, Helen, traveled to New Hampshire to a backwoods camp near Lake Squaw. The couple roughed it, sleeping on birch cots under thick blankets, relaxing around a fire, traipsing through autumn woods dappled like red apples and honey. It was the antithesis of his fast-paced urban life, and Babe loved it. Only his voracious appetite followed him from the city. (On this trip it was rumored Babe ate half a pig at one sitting).

The pair soon after purchased a farm in West Sudbury just south of Boston, where Ruth would emulate the life of “a country gentleman,” while Helen, no doubt, prayed the rural setting might corral the beast in Babe. Though Helen had little luck with the latter, Babe enjoyed squiring it up — hunting, fishing, chopping wood and raising livestock. He became a serious ice fisherman and enjoyed fox hunting with courtly teammate Herb Pennock. One photo of the period pictures Babe in plus fours and tweeds, dandy as any English grouse shooter. In another, he is resplendent in knee-length leather boots and a carefully tailored shooting suit.

The Babe with fellow sportsman Pierre McCormick and their bag of pheasants and rabbits.

Not all of Ruth’s early sporting experiences matched his sartorial splendor. On one well-chronicled outing at Sudbury, Babe and his guests drank heavily until late in the evening when they donned hunting togs and grabbed their guns. Soon the night was alive with gunfire; down at the pond Ruth and friends were making short work of the estate’s amphibian population, blowing bullfrogs to bits with their shotguns.

Another time in 1921, Ruth spent a day riding a thoroughbred after foxes with Herb Pennock. That evening they went coon hunting, where Ruth proved helpless in the face of his legendary late-night appetite. Lacking other sustenance, Babe grabbed an ear of corn off a stalk, then devoured half of it raw as eagerly as he might a ballpark hotdog.

During his halcyon days with the New York Yankees, from 1920 to 1932, Ruth refined — or at least broadened — his sporting tastes around the country, hunting in the months after each ball season and fishing during the summer. As Babe’s second wife, Claire, noted, Ruth and teammate Lou Gehrig were equally “mad” about fishing. They were commonly seen together on piers and charter boats around New York. While in spring training each year in St. Petersburg, Ruth avidly fished Florida’s waters.

Another southern haunt was at Dover Hall in Georgia, a hunting hangout for baseball’s royalty It was here that Ty Cobb, a bigot and rabid rival of Ruth, made his infamous comment about the origin of Babe’s swarthy complexion and flaring nostrils. Cobb complained after being told the pair would share lodging, “and I am not about to begin now in my home state of Georgia:’ Cobb was as ugly a racist (and wrong in this case) as he was great a baseball player.

In his prime, the press breathlessly followed Ruth’s exploits, including those afield. Babe was often photographed in his ubiquitous tan camel’s hair coat clutching game of one sort or another. While quail hunting once in south Florida, Babe, George Pipgras and several other Yankee players were “attacked,” as the New York Times wrote, by a large rattlesnake. “Ruth stepped within striking distance of the curled rattler,” the Times chronicled. “Babe heard the snake’s warning but before getting out of range Pipgras’ hound dog jumped at the reptile as its truck at Babe and received the snake’s fangs in its leg.”

The Bambino’s reaction was typically Ruthian. “Whirling around as he leaped,” the reporter wrote, “Ruth fired, blowing off the snake’s head.”

The vigor of field sports were no doubt appealing to a man who craved action and constant physical pleasure, be that from batting balls, eating and drinking in excess, or from the pursuit of sex. Babe also loved the camaraderie of the campfire; the drinking, cursing, spitting in the fire, pissing in the woods. The forest, too, offered sanctuary from rules and regulations, which Ruth despised. In a real sense, the whole hunting ritual of “getting away” codified and legitimized Babe’s headlong flight from societally imposed restraints.

Of course, hunting and fishing were also fashionable pastimes for the wealthy, particularly the Old Rich, the distinguished gentry of the countryside to which Ruth occasionally aspired. While all of this partially explains Ruth’s participation in field sports, none of these factors alone completely explain the passion with which he pursued them. No one endures ice fishing willingly, after all, unless they truly enjoy it.

Though he was never considered a reflective man, I think Ruth simply found hunting and fishing engaging and intensely absorbing — just as mortal nimrods did (and do). For Babe, the backwoods were probably restorative, at least if you believe what he told the newspapers. Following his disastrous 1925 season with the Yankees, a debauched Ruth left for a three-week hunting trip to New Brunswick to purify himself of urban excesses. He was said to have returned “a new man” and one companion spoke of an energized Babe embarking upon a 40-mile hike through the wilderness. His trainer, however, offered a different opinion upon the slugger’s return, declaring Ruth a “physical wreck.” Whatever the truth about this trip, hunting and fishing kept Ruth relatively fit while the baseball stadiums were empty.

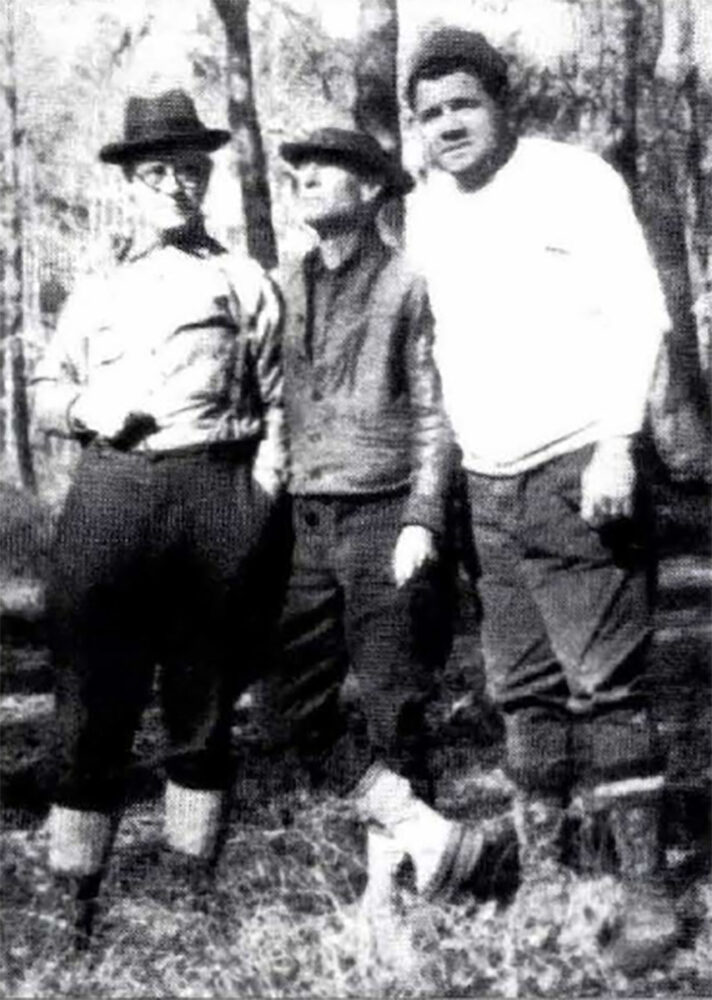

In the latter half of his career with the Yankees, one of Ruth’s favorite hunting retreats was Camp Bryan, near New Bern in eastern North Carolina. Camp Bryan still exists — smaller now after considerable club property was sold in 1948 to become national forest — but it remains an exclusive hunting and fishing retreat for some of North Carolina’s wealthiest and best-connected citizens.

Today, members of Camp Bryan have their own individual cottages — some simple, some sumptuous but in the 1920s lodging was little more than a pair of primitive shanties set amongst 50,000 acres of swamp forest. The camp was founded in 1898 by wealthy locals, including George Nicoll, a rich Bostonian transplanted to North Carolina. Nicoll had, in turn, recruited some of baseball ‘s elite, notably Frank Stevens — the “Hotdog King” — whose family business operated concessions in many of the major ballparks of the day, including the Polo Grounds and, later, Yankee Stadium.

Frank was to become one of Babe’s life-long hunting partners and through his influence, Camp Bryan became a winter pilgrimage for famous writers and baseball players: wordsmiths like Irvin Cobb, Rex Beach and Bud Fisher (of Mutt-and-Jeff fame) and baseball legends like Christy Mathewson, Charlie Keller, Lou Gehrig, George Sugg and, of course, Babe. Ed Barrow, general manager of the Red Sox and, later, the Yankees, was another winter habitué.

Ruth began visiting in 1927 or ’28 and hunted the camp for at least the next five winters. He fell in love with its homey atmosphere, and particularly the cornbread, collards and com “likker” plied by camp cook Dave Sampson, an ex-slave whose game cooking and cheese biscuits are still recalled reverentially Sampson, apparently a raconteur of first order, was beloved by members and guests alike, and Ruth became immensely fond of him.

Babe at a shooting preserve in California with several Yankee teammates including Lou Gehrig, third from left.

At camp, baseball business and intrigues were quickly forgotten. When asked in 1932 by visiting reporters about planned Depression-induced salary cuts, Babe gave a “huge and prolonged yawn” and replied, “I have nothing to say.” Days were instead spent hunting while evenings were given over to drinking, card games and resting around a huge fireplace. The guests rarely shaved and their dress, observers noted, would have shamed a hobo. Dave Sampson kept the table well-lardered with Southern delicacies, providing Babe a stage to display his ample talents with knife and fork.

“Ruth’s Prodigious Appetite Amazes Cook” was the headline from his 1932 trip. The camp’s Sunday dinner that year featured a wild turkey shot by Ruth, roast ham, boiled ham, Irish potatoes, sweet potatoes, collards, cornbread, toast, coffee, cake and pies. “He didn’t eat as much breakfast,” the cook told the newspapers. “Only two eggs, when he usually eats five or six — and two or three links of sausage and I don’t know about how much bacon and about a loaf of bread made into toast.”

Mornings began with a deer drive and afternoons were spent shooting doves, turkey, quail or reared pheasants. Other days featured duck and goose hunts on some of the camp’s five natural lakes. When the guests wanted open-water gunning, they would travel to the towns of Oriental and Davis on nearby Core and Pamlico Sounds to shoot divers, brant and geese from stake blinds. One morning’s hunt on the Sound with Frank Stevens yielded over 40 ducks.

Ruth particularly enjoyed hunting deer from a tree stand and was described as “an inveterate climber.” According to published accounts, the Bambino was an excellent wing shot, once dropping five birds in as many shots at Camp Bryan. As with any mythic figure, it is not always easy to winnow legend from reality, in this case Ruth’s actual skills as an outdoorsman. One living eyewitness to Ruth’s hunting feats is the son of Rolan Taylor, who was the caretaker at Camp Bryan from 1928 to 1935. The son, who today lives in South Carolina but wishes to remain anonymous, helped his father maintain deer stands, duck blinds and the roads. He often accompanied Ruth into the woods.

“He was a better shot with his bat than with a gun,” Taylor told me. “Of course, it may have been the circumstances.” On the specifics of those “circumstances” the caretaker’s son remained guardedly mum, but one suspects Ruth’s campfire indulgences — notably Dave Sampson’s moonshine — may have soused his shooting eye on more than one occasion.

Taylor chuckled about one of Ruth’s adventures. While deer hunting one Saturday, an eight-point buck slipped by Ruth unnoticed and began wading the shallows of Little Lake in an effort to escape the pursuing hounds. The boy, then accompanying the dog handler, pointed out the escaping buck. “Hey Babe! That deer got by you!”

The trio gave chase in a small boat with Babe in the bow, the caretaker’s son in the middle and the guide poling on the stern. As they closed on the buck, it began leaping through the shallow water. Babe stood up and cut loose with his rifle — firing seven shots from a .35 Remington. The guide, too, also began firing.

“Both men were missing the deer so I decided to take a shot,” Taylor said. “Ole Babe was standing up straddle-legged in the bow and I was sitting so close that I couldn’t shoot around him. So I took my little .22 rifle and stuck it (unnoticed) between Babe’s legs. When the deer jumped and fell back to the water I fired. The buck jumped a couple more times and fell over.”

Babe, absorbed in the excitement and distracted by volleys of gunfire, yelled, “Damn it, I got him! I got him!” As they dragged the buck into the boat, the boy felt for the killing shot — one tiny bullet hole in the chest with no exit wound. “After that I knew doggone well who got that deer,” Taylor laughed. The next day, though, the local paper proclaimed, “Babe Gets Eight-Pointer.”

But it would be inaccurate to suggest that Ruth was nothing but a buffoon with a shotgun in one hand and a shot glass in the other. Babe could be a serious hunter, and a good one too. In her book The Babe & I, Claire Ruth wrote that Babe was as proud of shooting one big wild turkey as he was of any of his “diamond exploits.” Another time he spent seven hours in the Georgia woods carefully stalking a gobbler before dispatching it with a single shot.

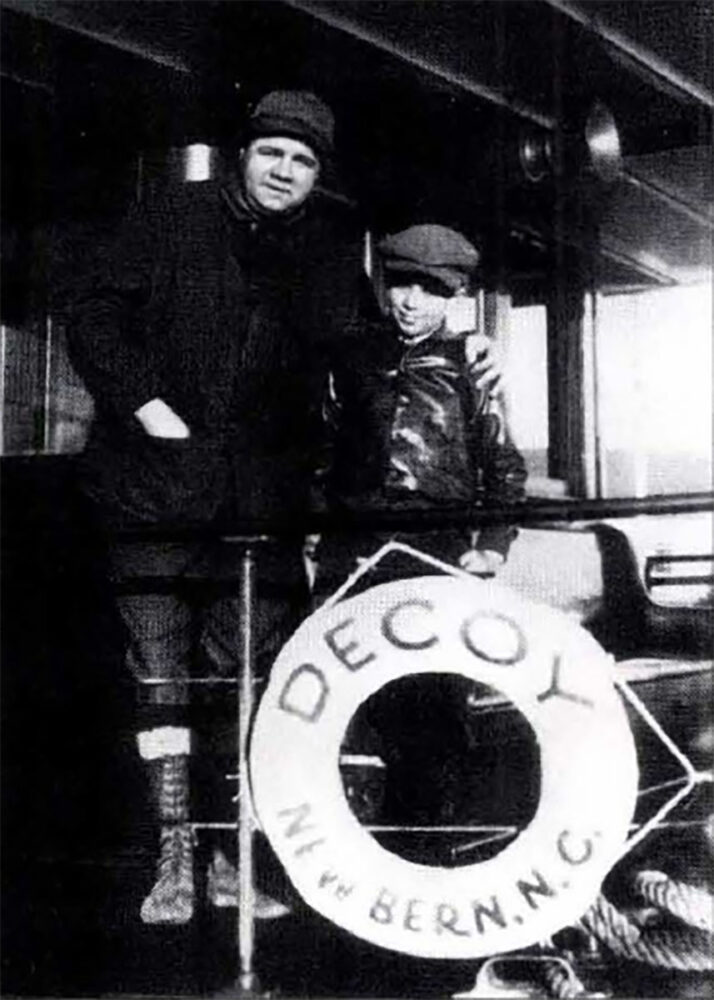

Babe Ruth with Fred Sutton, Jr., the son of a wealthy Camp Bryan member. Babe’s love of kids was no act; he was friendly even when the cameras weren’t around.

Babe, the perpetual showman, reveled in displaying his trophies. In November 1937, he was photographed next to his blood-spattered car in Manhattan just back from a trip to Nova Scotia, one deer strapped across the front bumper, two more on the fenders and a black bear bulging from the bumper seat. Ruth had shot a huge 13-point buck, and he asked reporters, “Did you get a slant of that 13-pointer? Some baby!” Then, commenting about an upcoming charity golf game, “I hope I can drive and putt as well as I can shoot a gun.”

Though a man of Babe’s financial means could have afforded a matched pair of Purdeys and more, the “Sultanof Swat” preferred raw firepower to the subtleties of hand-made English guns. He was usually photographed with repeating firearms — a plain Browning Auto 5 his shotgun of choice.

Ruth enjoyed eating what he shot. Claire wrote of Babe’s pride in carving venison and other game for guests, recalling his pleasure at “showing off his unexpected skill” with the knife. He would concoct barbecue sauce “by the gallon” to take on trips afield. Claire occasionally accompanied Babe, once even to primitive Camp Bryan, but soon gave it up after deciding “hunting was for the boys.” Her brothers, however, remained some of Babe’s favorite hunting companions.

After his skills with the bat slipped in 1933 and 1934, Ruth hoped to transition from player to big league team manager— baseball was, after all, still his life, the basis of his entire persona, public and otherwise. He actively courted a managerial position with the Yankees but Ed Barrow remarked, “How can he manage other men when he can’t even manage himself?” In winter 1935, Ruth’s last days as a Yankee, reporters asked about his future plans. Babe told them he was off to upstate New York to “shoot some peasants.”

“You mean pheasants.” they corrected.

“I guess so — birds, anyway.”

But the malapropisms and impulsiveness that delighted the masses endeared him not to team owners. After one final ill-considered season with the Boston Braves, Babe retired in June 1935, then waited in vain the rest of his life for an offer to manage that would never come.

Baseball had turned its back on Babe — a devastating personal tragedy for the aging Bambino. He repressed his self-described “despondency” with golf, bowling and hunting and fishing. Whereas field sports once offered Babe refuge from the bright lights of the ball field, they now distracted him from the void left by baseball’s absence. In truth, the links, the woods and the water supplied solace, but probably never brought Babe any real peace. Still, his stature as a demigod assured his hunting grounds would continue to be the country’s finest, his companions governors, sportscasters and the nation’s richest men.

His tastes afield were catholic; with equal aplomb he pursued bear and deer in New Brunswick, ducks and woodcock in Nova Scotia, trout and salmon in Maine, rabbits and pheasant in New York, and blue-water species in Hawaii. Babe and Claire loved Florida and in retirement wintered each year in St. Petersburg. He continued to fish the Gulf waters with enthusiasm.

Despite a growing bitterness for organized baseball, Babe remained a “humanitarian beyond belief,” as Robert Creamer noted. His love of kids was legendary and genuine. Far from the cameras, at remote outposts like Camp Bryan, his charity to kids and to those less fortunate never dimmed. To the sons of Camp Bryan’s caretaker, he gave a dozen autographed baseballs. “Babe always took time to horse around with us,” Taylor remembered. “He was very personable.”

His appearances in nearby Morehead City, Havelock and surrounding North Carolina towns drew throngs of kids; school was even let out early one day so students could see Babe. The sons of waterfowl guides vied for the honor of carrying his guns, gear and game. Babe is still remembered locally for his friendliness to children, his smile, his lavish tips and his drinking.

Carl Goerch, publisher of The State magazine, was a guest at Camp Bryan when Ruth visited. He recorded Ruth’s reaction when told Dave Sampson was mortally ill. Cursing, Ruth demanded to be taken to Sampson’s cabin, where he found the black man in his rocking chair, weak and ailing. “Dave you old (expletive),” Babe roared. “What in the hell do you mean loafing here at home when you ought to be down at the camp cooking me some buckwheat cakes!”

Babe pulled up a chair and sat joshing with his friend for 15 minutes. “It was evident that he had a deep affection for the old cook,” Goerch wrote. “Babe watched for his opportunity when he thought neither Fred or I were watching and then slipped two or three bills into the old man’s hand.”

“Lord bless you, Mister Ruth.”

Babe with Frank Stevens and George Nicoll at the exclusive Carolina retreat.

Babe played the sportsman through his last decade, even after cancer began to gnaw away his health. One of the saddest photos pictured the cancer-ravaged Babe in Florida in April 1947 next to a 50-pound sailfish whose 30-minute struggle left him “whipped.” Still, the smile is there, as well as a cigar clamped defiantly in his hand. In mid-May of the following year, Ruth and Claire returned to Florida where Babe golfed, basked in the sun and fished the Keys a final time. In three months, the great man would be dead.

Sportsmen cherish friendships forged in the outdoors because true character reveals itself so clearly through the rituals of field sports and their unwritten codes of behavior. Babe’s backwoods exploits are edifying not so much for what they revealed as for what they did not. There was no hidden malignity laid bare in a duck blind or deer stand, after all. Ruth was hardly perfect afield — he wasn’t anywhere — but he was never out of character. He was complex, paradoxical, sublime, sometimes sorry, but most of all he was a man who anyone would have loved to meet — on the baseball field with a bat or in the woods with a gun.

Author’s Note: I must thank the following for their kind assistance with this article: Robert Creamer, author of The Babe, Billy Arthur, North Carolina news legend; Courtney Mitchell, Jr. for a tour of Camp Bryan; and especially Jack Dudley, author of Carteret Waterfowl Heritage, for his generosity with references and photos.

A superb collection of stories that captures the very soul of hunting. For hunters, listening to the accounts of kindred spirits recalling the drama and action that go with good days afield ranks among life’s most pleasurable activities. Here, then, are some of the best hunting tales ever written, stories that sweep from charging lions in the African bush to mountain goats in the mountain crags of the Rockies; from the gallant bird dogs of the Southern pinelands to the great Western hunts of Theodore Roosevelt. Great American Hunting Stories captures the very soul of hunting. With contributions from: Theodore Roosevelt, Nash Buckingham, Archibald Rutledge, Zane Grey, Lieutenant Townsend Whelen, Harold McCracken, Irvin S. Cobb, Edwin Main Post, Horace Kephart, Francis Parkman ,William T. Hornaday, Sc.D, Rex Beach, and more. Buy Now

A superb collection of stories that captures the very soul of hunting. For hunters, listening to the accounts of kindred spirits recalling the drama and action that go with good days afield ranks among life’s most pleasurable activities. Here, then, are some of the best hunting tales ever written, stories that sweep from charging lions in the African bush to mountain goats in the mountain crags of the Rockies; from the gallant bird dogs of the Southern pinelands to the great Western hunts of Theodore Roosevelt. Great American Hunting Stories captures the very soul of hunting. With contributions from: Theodore Roosevelt, Nash Buckingham, Archibald Rutledge, Zane Grey, Lieutenant Townsend Whelen, Harold McCracken, Irvin S. Cobb, Edwin Main Post, Horace Kephart, Francis Parkman ,William T. Hornaday, Sc.D, Rex Beach, and more. Buy Now