Although Robert Ruark was regularly exposed to dangerous animals during his hunts, and though he had a great many narrow escapes, he only got hurt once.

This happened on shikar in 1962, in the Madhya Pradesh region near Betul in Central India. There, a wounded leopard attacked Bob and inflicted serious injuries to his arm and shoulder.

This happened on shikar in 1962, in the Madhya Pradesh region near Betul in Central India. There, a wounded leopard attacked Bob and inflicted serious injuries to his arm and shoulder.

As had been the case on a previous Indian shikar, Bob was again accompanied by Ginny. She had expressed a special wish to return to India. On his previous visit Bob had an experience that would have led one to assume he knew the dangers associated with dealing with wounded animals. At that time, he had shot three tigers, though after about half an hour, one of them got up and walked away.

On the 1962 shikar, Bob had been hunting a tom leopard with a water buffalo as bait. He had waited for hours before leaving his blind and returning to the dak bungalow. It appeared that the male leopard would not come to the bait because he was more interested in a leopard bitch in the area. As it so happened, when departing the blind Bob and his party accidentally stumbled upon the female in the middle of the road.

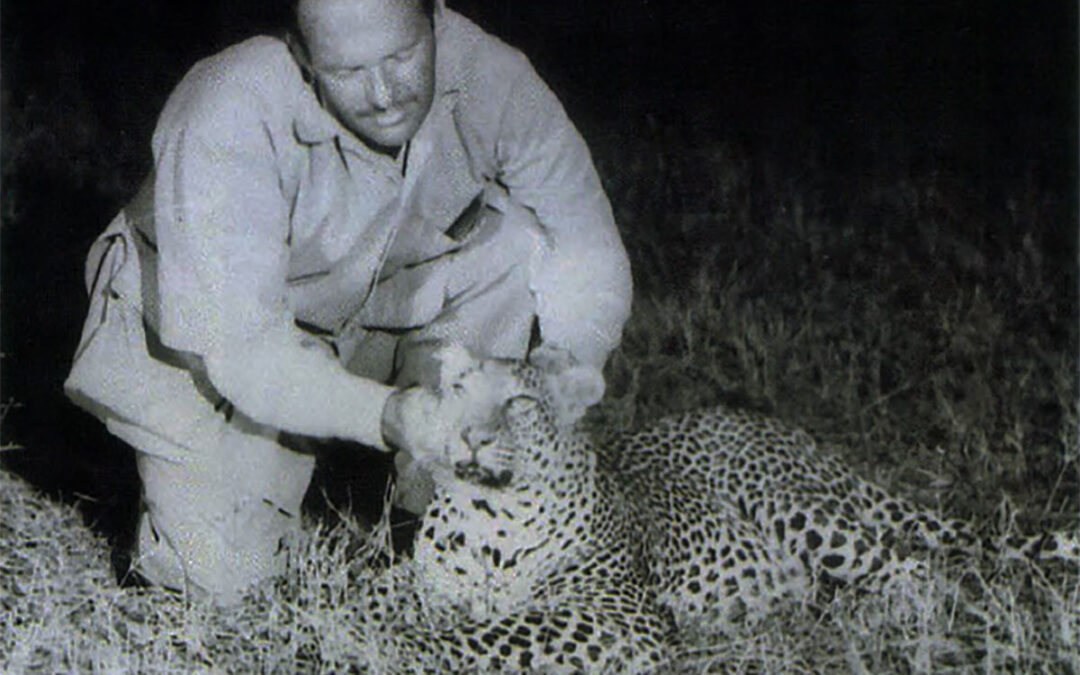

Bob afterwards said that he shot the female out of cold spite, and he admitted he broke an old rule about never shooting at night. Still, with the aid of a torchlight, he walloped her straight down the front with a rifle that had slain a hundred leopards. The animal appeared to be dead until one of the boys threw a rock. Despite the fact that two buckshot blasts had been fired into it from point-blank range of less than 10 feet, the leopard suddenly and violently came to life, flew into the air and landed on top of Bob.

Bob’s first shot had been fired from a .30-06 rifle, but the cartridge case had split and it was only with great difficulty that the jammed case was removed and another one placed in the breech. Meanwhile Bob’s companion, an Englishman resident in the area, was engaged in fending off the thrashing cat with the shotgun barrels rammed into her mouth. Bob was able to fire a finishing shot, somehow managing to hit the leopard and not his companion, who in the meantime had been badly hurt in the scramble. The Englishman probably saved Bob’s life, though the whole incident was made more hazardous by the Indian gun-bearers. At the first sign of danger, they ran away, taking the lamps with them. At the same time the moon disappeared behind a cloud.

Bob’s first shot had been fired from a .30-06 rifle, but the cartridge case had split and it was only with great difficulty that the jammed case was removed and another one placed in the breech. Meanwhile Bob’s companion, an Englishman resident in the area, was engaged in fending off the thrashing cat with the shotgun barrels rammed into her mouth. Bob was able to fire a finishing shot, somehow managing to hit the leopard and not his companion, who in the meantime had been badly hurt in the scramble. The Englishman probably saved Bob’s life, though the whole incident was made more hazardous by the Indian gun-bearers. At the first sign of danger, they ran away, taking the lamps with them. At the same time the moon disappeared behind a cloud.

By the time they killed the leopard, the two hunters were bleeding profusely. They tied tourniquets on each other and then started the 20-mile midnight drive back to camp. Of course, the wounds were bad enough, but serious infection was likely to follow. The more maggoty a kill becomes, the better a leopard likes it, so their fangs and claws are full of every possible disease.

On this Indian shikar many things were lacking, including a proper medical kit. So even after the men reached camp, the best that Ginny could do was to feed them gin to drink and use it to sterilize their wounds. Nothing else was available. They went to sleep in a drunken condition and naturally the next morning their wounds were terribly inflamed. Fortunately, there was a Swedish Lutheran mission in the little town of Padhar about 30 miles away. It was run by a British minister who stitched them up and supplied them with penicillin and tetanus shots, which undoubtedly saved their lives. Still, Bob had a very bad arm for many weeks afterward.

This whole fiasco could be directly blamed on faulty local ammunition. Afterwards, they found that the buckshot had barely penetrated the leopard’s skin. Not surprisingly, Bob was quite displeased with the way this shikar had been run, and not only because of the incident with the leopard. Before it happened, he had been out hunting at night and was frantically told to fire at something the Indian hunter had pointed out. Bob didn’t do it as he couldn’t see anything to shoot. After a little investigation, it was discovered that there was a dead leopard planted for him to shoot at. This was an insult to his intelligence as a hunter, and he was furious.

Owing to a general disagreement with the Indian shikar owner, it was necessary for Bob and Ginny to leave in a hurry. A heated argument about how much money Bob owed under the circumstances of a badly arranged, badly run hunt led to their hasty departure. According to Ginny, the shikar manager was off attending to other business instead of looking to the requirements of his clients.

So they made their way to a distant railway station with the intention of getting out of India as quickly as possible. They decided to carry out their original plan and make for Kenya, where proper medical attention would be available. Bob’s wounds were developing into a very serious infection and, as he said afterwards, “the liquor laws were more flexible.”

To relieve his general annoyance at the shikar, Ruark unleashed his wrath against a U of India. He wrote a number of political pieces criticizing the country and the fact she continued to beg from the U.S. even while having more gold tucked away secretly than any country in the world.

These pieces were dictated from his hospital bed in Nairobi. He figured that his series on gold hoarding cost India a quarter-billion dollars in aid from the United States, as at the time there was a bill being debated in the Senate that was defeated.

Bob advised all tourists to avoid India because of the country’s ludicrous prohibition laws, excessively suspicious customs and a booking system for trains that required constant and considerable bribery to get anywhere at all. He didn’t like the unusually slow system of state banking, and among other things noted that there was a tendency for Hindus to give short weight and supply shoddy goods.

When vexed, Bob could be quite ruthless in his criticism, but on the other side of the coin he wrote a column praising the work of the mission where he had been treated for his leopard wounds. Here quested financial help to build a new hospital at the mission, and this got some response from donors. A complimentary reference was also made concerning the American Consular Service in Bombay, which had helped him get out of the country.

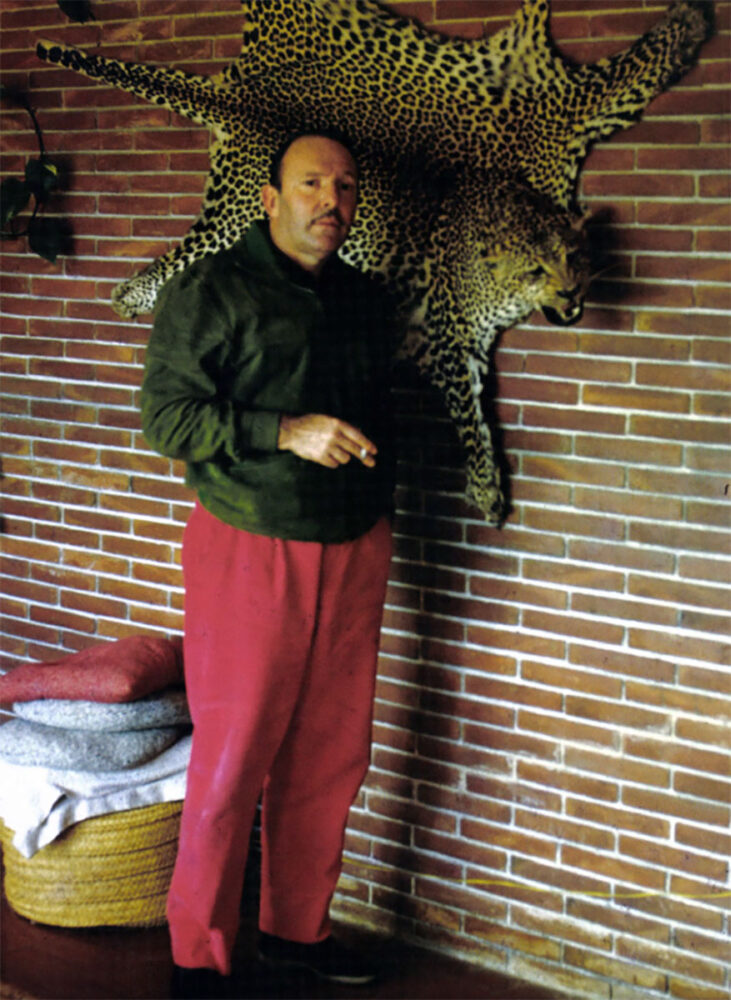

All the unfortunate occurrences on this Indian trip notwithstanding, he subsequently got a great deal of mileage out of the leopard attack. He not only wrote numerous pieces about animals that fight back, but often, when showing his war wounds, he would also include his leopard scars. This always seemed to finish any discussion as to who had seen the most action.

All the unfortunate occurrences on this Indian trip notwithstanding, he subsequently got a great deal of mileage out of the leopard attack. He not only wrote numerous pieces about animals that fight back, but often, when showing his war wounds, he would also include his leopard scars. This always seemed to finish any discussion as to who had seen the most action.

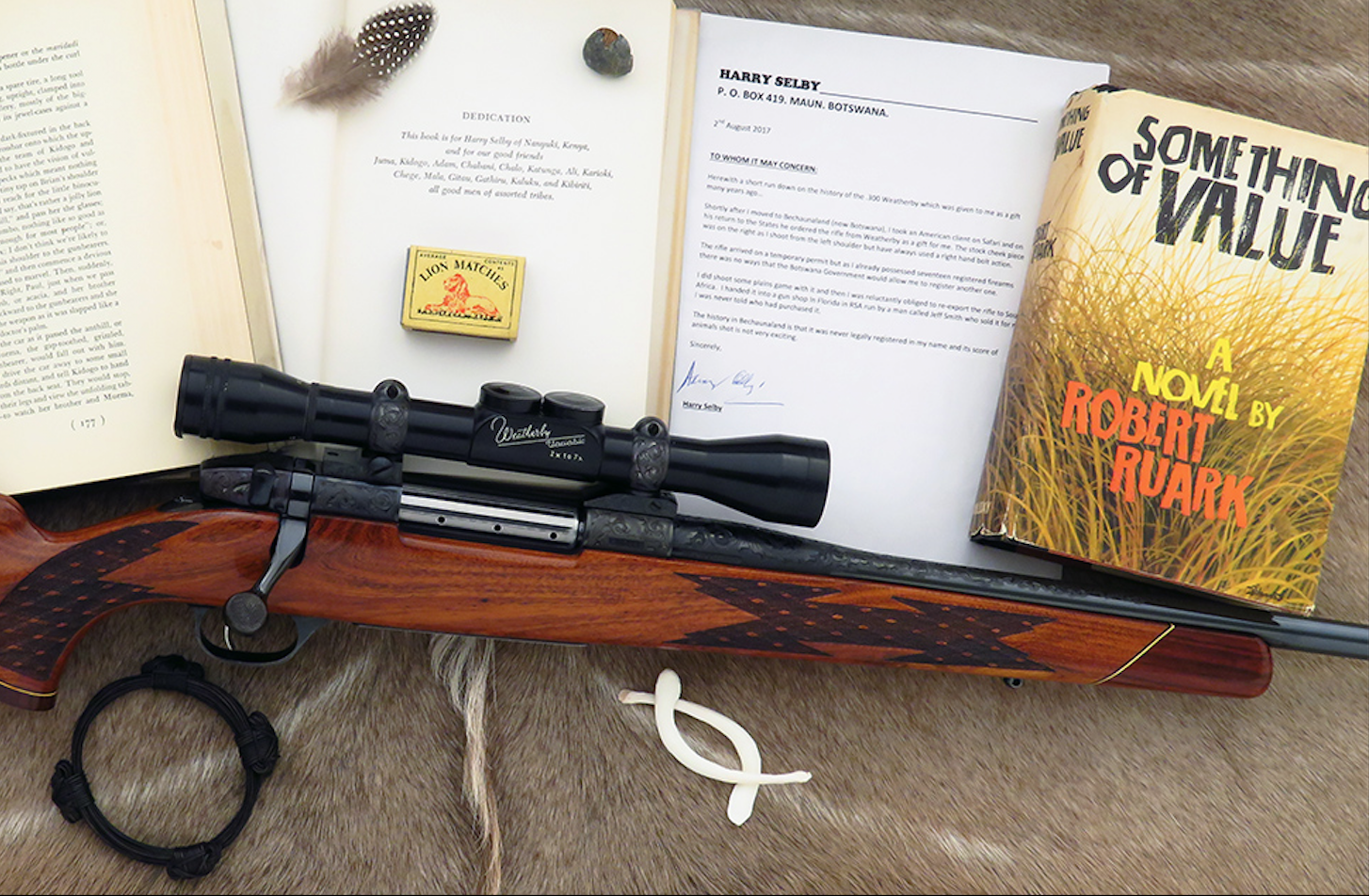

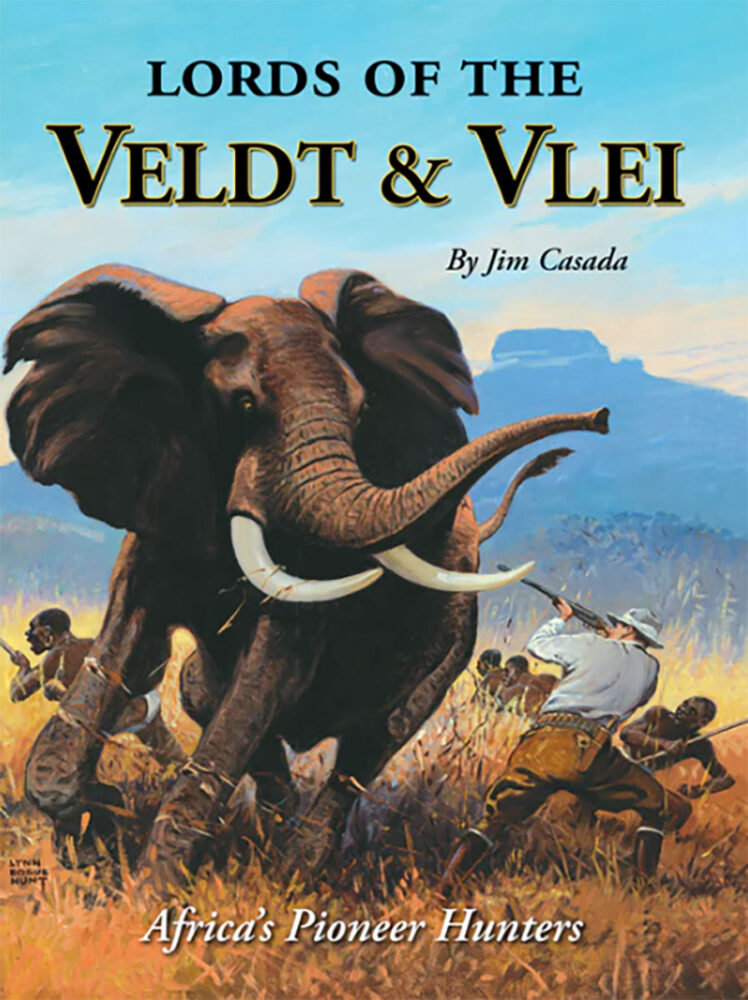

This account looks at some of the mightiest and most mesmerizing of these Nimrods, chronicling their careers while highlighting their eccentricities, delving into the factors that drove them, and sharing their achievements. Each profile is accompanied by a selection from published accounts by these pioneers of African sport, and dozens of vintage photographs and captivating pieces of art that offer a striking visual accompaniment to this saga of splendid sport. Buy Now

This account looks at some of the mightiest and most mesmerizing of these Nimrods, chronicling their careers while highlighting their eccentricities, delving into the factors that drove them, and sharing their achievements. Each profile is accompanied by a selection from published accounts by these pioneers of African sport, and dozens of vintage photographs and captivating pieces of art that offer a striking visual accompaniment to this saga of splendid sport. Buy Now