Cooking on wood is like blowing a goose call or a trombone. Showing you is easy, telling you is hard.

The scud stacked up over the northeast, a gray washboard above the sea, to the horizon and beyond. Too late for a hurricane, but the wind didn’t care. Raindrops big as dimes on roofing tin and window glass, a racket like the devil beating some hellish rhythm on a snare drum. You never heard such.

The power flickered, faltered, failed.

No worries.

A generator ran most of the house, Colemans and kerosene took up the slack. And then there was the wood stove, an old-fashioned range, the kind your grand-mammy likely had if you came up Southern and rural like me.

There was a bushel of wind-fall hickory right handy, a handful of fat lighter on top. I opened damper and draft, struck a match. About three minutes into the satisfying roar, I closed the controls. The stove shuddered, mumbled, popped, clicked, ticked and vibrated as the heat rolled across the kitchen in a great comforting wave.

Venison chili for supper, biscuits on the side with a generous drizzle of cane syrup for dessert.

Blow ye winds hi ho!

Cooking on wood is like blowing a goose call or a trombone. Showing you is easy, telling you is hard.

Kinda like getting along with a woman, more art than science, forgive my candor. Every range is unique, and every chimney draws differently, ofttimes contrary, depending on what you feed it, wind direction and velocity, humidity, even barometric pressure.

Alas, telling you is hard, but I am fixing to try.

“Raise up a child in the way he shall go,” the Good Book says, “and as an old man he shall not depart from it.” I found sufficient inspiration in my granny’s kitchen. Three stoves, two wood and one kerosene. Kerosene was employed summer months when a wood range would run you clean out of the house. Of the two woodstoves, one was for cooking and the other was looped into the plumbing and provided endless hot water.

But I never remember my grandmother using any of them. She gave this marital advice to my mother: “A lady should never learn to butcher chickens, shuck oysters or split kindling.” She had Elvira Mike for all that, more family than employee for thirty years. Elvira could rattle some serious pans.

But I never remember my grandmother using any of them. She gave this marital advice to my mother: “A lady should never learn to butcher chickens, shuck oysters or split kindling.” She had Elvira Mike for all that, more family than employee for thirty years. Elvira could rattle some serious pans.

Elvira’s cousin, Booker T. Washington Stokes, ran a regular ad in the local classifieds: “Lots of wood lying around? Don’t curse. Something new, a power saw.”

It was not a chainsaw. Nobody in those days had seen, or even heard of such, but a buzz-saw mounted on the back of a Model A Ford pickup. Booker T. would jack up the rear end, remove one tire and replace it with an empty rim. A belt riding in the groove powered the saw, a wicked forty-inch open blade calculated to give an OSHA man cardiac arrest, but we did not have OSHA men in those days. My aunties kept me clear, thirty yards, at least.

It’s a God’s Wonder nobody lost an arm. Colonial cooking was on open massive brick fireplaces. Hand-forged iron eyelets set into the bricks supported a boom that supported a pot that swung over the fire and back again as needed to maintain proper temperature. Broiling was done on a rack alongside the coals with pan to catch the drippings and baking in a Dutch oven buried in hot ashes.

It was better than cooking in the yard, but not much.

An open hearth was spectacularly inefficient, expending much fuel and creating an updraft that sucked heat out of the room long after the fire was out, not to mention flying sparks to set a house afire. Ben Franklin is credited with the first fireplace insert, a response to a wood shortage in Philadelphia in 1741, a cast iron contraption that still bears his name. Most Franklins featured a flat top for stovetop cooking and some even had ovens attached to the sides.

From simple two burners in the 1840s, by the 1890s, the “Golden Age” of American wood cookery, a typical range might be a nickel, enamel and chrome-trimmed cast-iron behemoth with an oven, a broiling oven, a pair of warming ovens and a hot water reservoir, tipping the scale at upwards of a half-ton. They were, and remain expensive, though the cost was somewhat mitigated by the minimal masonry required. All a range needed was a simple flue and a fireproof floor beneath, brick or tile. By 1900, 40 million American homes depended on wood for cooking.

A child in the way he shall go. I bounced around a bit, wood cooking dreams on hold, as you do not casually drag a wood range into your typical rental unit. First house I built for myself had two chimneys, one for a wood heater, one for the range.

This is how it works. Heat rises and in the controlled environment of a wood range, combustion continues in the lower chimney. The rising and rapidly expanding column of gasses creates an updraft that sucks fresh air into the stove at the other end, oxygen to feed the fire. The hotter the stove gets, the hotter it can—and will—get. This necessitates some sort of throttle, an adjustable draft to regulate incoming air and a damper on the flue to control the chimney updraft. Ben Franklin, copying the work of several European predecessors, realized once the stove and flue were drawing correctly, the updraft was so powerful, it could even pull heat and smoke down, in an action he called “a reverse siphon.” Thus, a third control, the oven regulator.

Inside a cold stove with the oven off, flames rise from the firebox, travel across the top of the oven to the chimney pipe. Once the stove gets to ripping and roaring and draft and damper closed, close the flap atop the oven and the smoke goes down and around the oven before exiting via the flue. Some stoves have a thermometer set into the oven door, others you buy a little gizmo and hang it from the rack inside. If the oven gets too hot, which they are sometimes prone to do, just tickle the oven flap until it maintains 375 degrees, the optimal baking temperature. If you are baking a pizza, you can run it up to 425 should you like.

Brothers and sisters, I am here to testify, a wood stove will make the cheapest take-and-bake from the stop-and-rob convenience store taste like the Pride of Little Italy. And don’t ask why a cauldron of Geechie Boy’s yellow stoneground speckled grits tastes better cooked on wood rather than electric or gas, but it damn sure does.

No knobs on a wood range, but don’t let that throw you. Just slide the skillets around. Between the firebox and the oven is the hottest. Far right will keep food warm ‘til you belly up to the table. In between is whatever you want. If your stove has warming ovens, use them. Never throw a steaming slab of cornbread on a cold plate ever again.

No knobs on a wood range, but don’t let that throw you. Just slide the skillets around. Between the firebox and the oven is the hottest. Far right will keep food warm ‘til you belly up to the table. In between is whatever you want. If your stove has warming ovens, use them. Never throw a steaming slab of cornbread on a cold plate ever again.

Care and feeding? Easier than you think. Dry hardwood, cut short and split small. Think sticks a foot long as big as your wrist. Fat lighter for kindling atop wastepaper from the kitchen, three, four little sticks should do it, a bushel will last all year.

Keep close watch for the first hour or so, feed it every three songs on the radio, the city-bred wife says. After a couple of hours, once the three or four hundred pounds of cast iron gets blistering hot, check it every forty minutes. A couple sticks of greenish wood will tamp things down should the stove get too hot. Figure on hauling out the ashes every two or three days, good for the garden if you have one. There’s commercial stove polish—applied cold, of course—should you wish to spiff up your pride and joy when company comes.

As you should.

And never neglect to glory in your social responsibility. Damn fine vittles while consuming a renewable resource? Participating in a carbon-neutral endeavor while sidestepping greedy multi-national energy corporations? That’s a mouthful, but guaranteed to please the skeptical.

Heating the whole house? I’ve had wood heaters too, way up in Minus Forty Yankeeland, everything from homemade barrel stoves to a mega-dollar Jotul, a favorite of well-heeled wood heat hippies in a dozen nations. But here in the land of buckwheat cakes and Injun batter, a good range is all you really need.

I cook supper on the range while the HVAC loafs. Load the stove one final time when I turn in and long about 3 a.m., I grin when I hear the HVAC kick back in. That’s supper and twelve hours of heat on a six-gallon pail of stovewood. And here on this hurricane coast, hickory, black cherry and water oak rots before I can ever burn half of it. I have yet to cut a living tree.

If you think this is all a lot of trouble, you’re right. But fear not, you can learn it if you want and if you do, you will be mighty happy you did.

And that’s a promise.

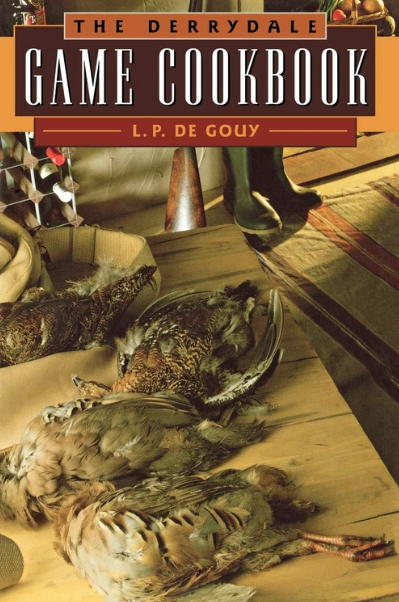

Like the hunting and fishing classics Derrydale published in the 1930s, this cookbook has only improved with time. This is a no-nonsense, practical guide to cooking virtually every kind of wild game with everything from simple recipes to gourmet-level preparation.

Like the hunting and fishing classics Derrydale published in the 1930s, this cookbook has only improved with time. This is a no-nonsense, practical guide to cooking virtually every kind of wild game with everything from simple recipes to gourmet-level preparation.

L.P. De Gouy is the author of the Pie Book, The Soup Book, Sandwich Exotica, The Derrydale Fish Cookbook and more.