Tait worked hard at his craft, his sketches, his technique. It was this essential labor that helped him, when his imagination called, rise to the occasion.

American landscape and genre painting of the late 19th century, in which Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait excelled, is not a memorable subject aesthetically. What was then an immensely popular art is appreciated now as the flesh and blood of the nation it identified, not for any subtleties of style. But this strain of painting has vigor and variety; and look where you please, it beams with the pungency and energy of American life, in a manner that fine arts of the same era are hard-pressed to surpass.

American landscape and genre painting of the late 19th century, in which Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait excelled, is not a memorable subject aesthetically. What was then an immensely popular art is appreciated now as the flesh and blood of the nation it identified, not for any subtleties of style. But this strain of painting has vigor and variety; and look where you please, it beams with the pungency and energy of American life, in a manner that fine arts of the same era are hard-pressed to surpass.

The artists who made their marks at mid-century have been the most fortunate of any generation in our history. The nation was smitten with simple pictures; and artists of keen narrative and technical skill were able to practice the craft they loved without necessarily starving at the same time.

Among the notable lithographers who labored to meet public demand for art reproductions was the firm of Currier & Ives, active from 1835 to 1907. Over the years, this famous firm represented artists who, because of a certain innate eloquence, deserve rank above that of mere illustrators: Fanny Palmer, Charles Parsons, Louis Maurer and George Durrie, among those in the mainstream. And A. F. Tait, in his day Currier & Ives’ chief illustrator of sporting scenes, reportedly a skilled and strenuous woodsman, prolific, astute and self-taught.

Of all Tait’s good fortune, two events above any others seem responsible for sustaining him after his immigration to this country from England in 1850. The first was his discovery of the outdoors: the duck marshes around New Jersey and, more significantly, the unblemished lakes and woodlands of upstate New York’s Adirondack mountains. The vastness and vitality of the Adirondacks, very simply, inspired him; and in nature, on the periphery of civilization, he found a focus for his artistic intensity.

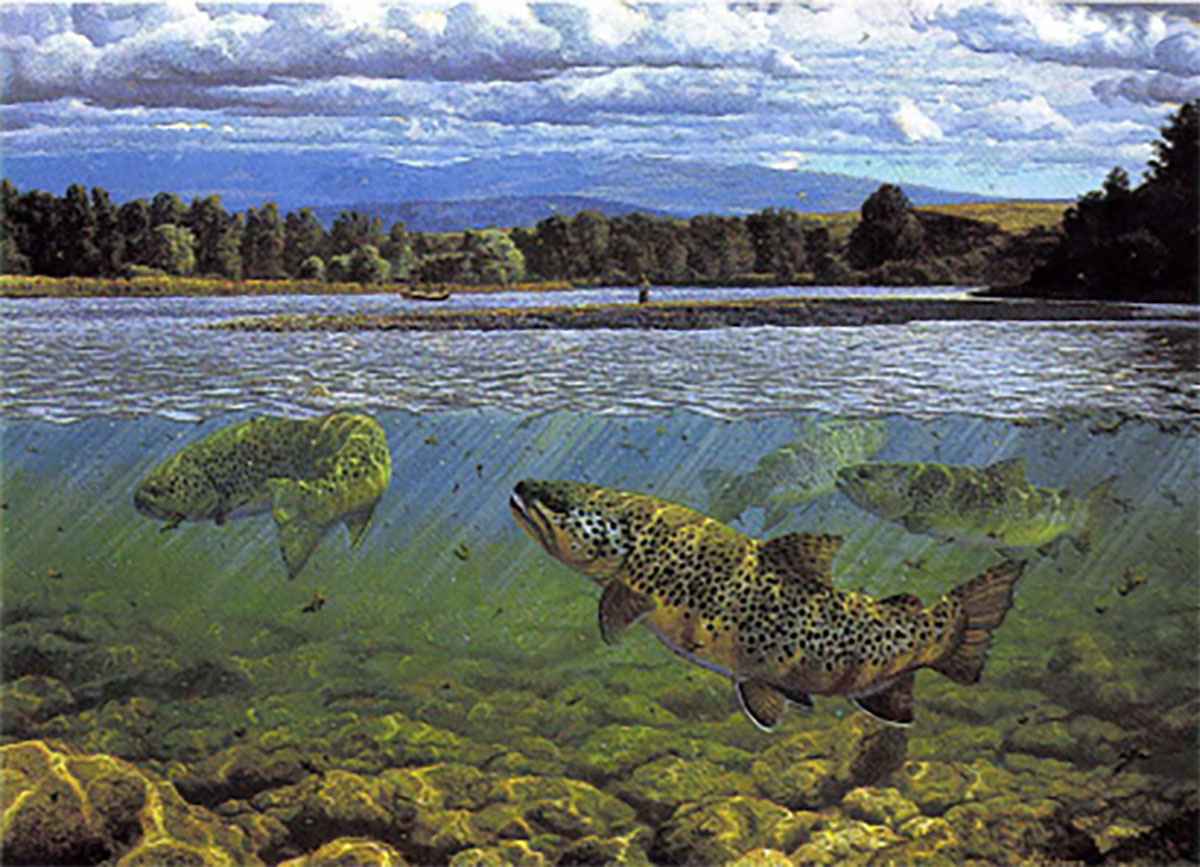

In his later years, Tait built a floating studio, a rustic houseboat which he used for solitary cruises around Adirondack lakes. He studied his subjects — deer, gamebirds, bear and trout — and sketched them in private, slowly. He did his best work amidst the quiet and purity of this wilderness.

The second incident of good fortune was Tait’s precise and uncanny collision with the spirit of his times. For a quarter of a century, his preoccupations, sometimes inadvertently, were those of his attentive public. He clarified what his viewers could only intuit; and in the public’s eyes Tait became, very rapidly, the incarnation of the American age he identified. Into his work he sifted moral sensitivity, gaiety and shrewdness, experiences from ordinary life, and to a degree, sentimentalism. In a word, he was a romantic, but marked by lucidity and directness.

Still Hunting On the First Snow: A Second Shot (1855) depicts Tait on a deer hunt in the Chateaugay Forest. Rumor has it that Mathew B. Brady, the famous Civil War photographer, is the other hunter.

Tait arrived in New York City with his wife and cousin at the age of 30, skilled in graphic arts, a minor painter and unknown. All that he knew about painting and drawing he had learned through self-instruction. He had desire. About that there was little question. At age 12, Tait regularly rose at 3 A. M. and gained entrance, through the kindness of a janitor, to the Royal Manchester Institution, where from its paintings and sculpture he first learned the fundamentals of draftsmanship.

Once in New York, Tait succeeded in selling several paintings to Williams, Stevens & Williams, a picture shop on Broadway, and to the American Art Union. But in trying to establish himself here as a professional artist, to even the marginal living he had left behind as a lithographer in Liverpool, Tait initially met with “difficulties and annoyances.” Judging from letters exchanged with his father, Tait at first perceived Americans to be woefully indifferent to art.

What exactly transpired during the first year of Tait’s residence in New York is the subject of conjecture. Information is sparse, the events simple; but his subsequent history indicates he was anything but idle. Tait quickly managed, with what must have been irresistible conduct, to get around. Within three years he had become a member of the New York Sketch Club, exhibited freshly completed sporting scenes at an exhibition by the National Academy for Design, and seen the first of some 40 of his canvases reproduced by Nathaniel Currier (later to be in partner with James Ives.)

It is known that Tait traveled repeatedly beyond the city for outdoor recreation, primarily hunting and fishing, and that upon returning from these excursions, carrying both game and sketches, he painted with oils for long hours in his residence on Spring Street. A good share of the canvases were studies of birds. Using wood ducks and mallards, snipe and woodcock, he constructed still-lifes of dead game set against a neutral background. This motif was the forerunner of the familiar hanging-game panels of Philadelphian William Hamett and his school, not to become popular until a full quarter of a century later.

In 1854, Nathaniel published a series of four prints based upon these still-lifes, entitled American Feathered Game. These are quiet paintings, simple and richly colored. They seem a commemoration of the new direction Tait sensed his life was about to take.

One of the first New York artists befriended by Tait was William Ranney, another sportsman and painter of outdoor subjects. Ranney, a man of wide travel, worked out of a studio cluttered with artifacts from the American West, a region which Tait understandably regarded with fascination. Intrigued, and with the necessary props at his disposal, Tait proceeded to experiment with several compositions using a frontier theme. The result was a series of dramatic paintings, usually involving trappers, buffalo and Indians. They are vivid creations, set in broad landscapes and wholly plausible, though Tait never visited the region he was painting.

Tait’s infatuation with western subjects was brief. He painted only 22 canvases, eight of which were reproduced by Currier & Ives. But these were his first paintings to truly stir the public’s imagination.

Duck Shooting With Decoys (1861) shows two Long Island waterfowlers.

They are exciting, with fierce Indians in pursuit of frontiersmen and buffalo charging before prairie hunters across open grass plains. They were successful in Tait’s time and have been so to this day, remaining among his most popular achievements. In 1980one prairie scene brought $200,000 at auction.

In his own day, Tait’s Currier & Ives reproductions, usually done in large folio and hand-colored, sold from $1.50 to $3.75. For his originals, he typically received $200. Beyond the generous fee, Tait enjoyed wide exposure. Currier & Ives lithographs accounted for three-fourths of the American print market and were circulated in the thousands.

Throughout the 1850s, Tait summered in the Chateauguay region of the Adirondacks. He stayed either in boardinghouses or camps, as long as they were remote, and made excursions afield under the auspices of one or more native guides. In what probably amounted to reciprocal attraction, Tait kept company with spirited, competent men. Certain of the guides, the Bellows brothers, Paul Smith, Jim Blossom and James and Seth Wardner are remembered to this day, in part for their association with Tait. They initiated him into the fabric of the region, its particular nuances. They taught him woodcraft, when and where to find grouse, to stalk deer, to make himself unobtrusive before rising brook trout. By the close of the decade, of the numerous tourists and artists who had begun to visit the Adirondacks, Tait was regarded by locals as the genuine article, a rugged, keen outdoorsman. That he had, by that time, achieved a national reputation as an artist, was incidental.

Tait necessarily encountered a lot of subjects. Some of them, specifically the white-tailed deer, he seemed disposed to use as a motif in his paintings repeatedly, to the point of excess. (Tait executed over 200 deer paintings.) Other subjects were rarely painted, with commensurately greater effect. One was the American black bear.

The bear of the Adirondacks unquestionably impressed Tait; some inscrutable characteristic in the animal moved him, compelling him to paint unsurpassingly well.

To obtain a specimen for close observation, Tait was willing, at least on one occasion, to circumvent his scruples. During one of his boat trips, in this case with his young son and the guide Captain Parker, probably on Long Lake, Tait encountered a swimming and therefore vulnerable bear. On her back was a cub.

Tait weighed the situation at hand. He was renowned for his sensitivity to animals, but he made a decision to close in and make a kill. It is interesting to speculate what sort of arguments, on the spur of the moment, he was constrained to wrestle with. Tait rationalized, one guesses, that for all art there must be a variety of sacrifices.

Motherless, the cub was taken home and used as a model. As it reached maturity, the bear, predictably, began to ignore its chain and victimize sheep and chickens. Until then, however, the half-tame bear was the subject of a variety of anatomical sketches and intimate study. It was this kind of scrutiny which enabled Tait, in the words of historian and critic Samuel Benjamin, to paint game “with remarkable truth.”

Motherless, the cub was taken home and used as a model. As it reached maturity, the bear, predictably, began to ignore its chain and victimize sheep and chickens. Until then, however, the half-tame bear was the subject of a variety of anatomical sketches and intimate study. It was this kind of scrutiny which enabled Tait, in the words of historian and critic Samuel Benjamin, to paint game “with remarkable truth.”

Tait must have studied the bear with unusual intensity, for his most mysterious, and to this author’s eye, riveting painting, is a portrait study. Entitled, without any embellishment, American Black Bear, it is an oddly surreal piece of realism. The bear is sprawled against a seamless white background, inert, eyes closed, with mouth parted slightly. A brown shadow line is the strongest suggestion of a third dimension. Almost abstract, this painting is a departure from and unlike any other painting of his career.

Tait worked hard at his craft, his sketches, his technique. It was this essential labor that helped him, when his imagination called, rise to the occasion.

Tait had heard the tale of two hunters and a black bear who had encountered one another in the Adirondack woods. The possibilities of the scene excited him. The bear, as the story was related to Tait, closed on the nearest hunter, who drew his knife. A fight ensued in the deep snow, during which, as Tait’s subsequent interpretation would have it, the poised hunter suffered clawing blows across one shoulder. The second hunter reportedly scrambled from the fray, with gun in hand, and waited for a clear shot. Behind them loomed an in finite forest and silence.

In 1861 Currier & Ives commissioned a painting from Tait based upon this incident. It became The Life of a Hunter — a Tight Fix, now the rarest and most valuable of some 7,000 different lithographic prints issued by Currier & Ives during the firm’s existence.

Apart from this distinction, the work is a sterling example of Tait’s reserved narrative power. The painting is dramatic without being theatrical. The bear’s claws are not dripping red; the man is not grimacing. Tait had the ability to discipline himself with restraint and discretion; and in the end, he turned what could have been a briefly startling image into a painting of unity and strength. It was the sort of achievement which had come to be expected of him by the New York art fraternity.

The Robber was exhibited in the National Academy of Design 27th Annual Exhibition under the title The Robber more Bitter than Sweet.

Tait’s prestige was on the upswing. Nearing middle age and with ten years in America behind him, he had already come and gone from, first, his Spring Street residence and next an apartment at 600 Broadway, an enviable Manhattan location in the midst of some 70 artists and their studios, print and picture dealers, and art supply shops. Tait had become an American citizen (1859). He was also a full member of the National Academy of Design and served as one of six men on the Hanging Committee, which gave him a hand in screenings and selections for major annual exhibitions. Currier & Ives was giving him steady work. Patrons and art entrepreneurs were buying his paintings. His work was selling at public auctions. It was a prosperous, happy period for Tait which was not to last.

One of the reasons Tait’s Currier & Ives reproductions are prized in this age is the quality of their printing. He pushed, when possible, for heavy paper and superior coloring.

As an experienced lithographic journeyman (from his younger years in England), Tait understood the medium precisely. He knew which details or peculiarities in his paintings would benefit from the lithographic process, and which would not. He painted his Currier & Ives assignments accordingly, with a view toward the end product. Tait insisted on reproductions that were faithful to his originals.

Apart from high technical demands, Tait was sensitive on the issue of form. Throughout his career, he never permitted a printmaker to alter one of his compositions.

The penalty — and distinction — of his standards proved expensive. In 1867, Currier & Ives took the liberty of reworking one of his animal prints and issuing it in a small, signed, inexpensive edition, without Tait’s permission. The artist took a dim view of this transgression and there after refused to conduct business with the firm, ending a fruitful, 12-year relationship.

It was a separation in which both suffered. In the previous decade, the popularity of one, to be sure, had grown with the other. Currier & Ives and Tait were mutually indebted.

In subsequent years, Tait turned to alternative markets. In the 1870s he learned that Laflin & Rand Company was considering the use of an illustration to assist sales of their “Orange Sporting Powder.” When offered the commercial art commission, Tait accepted and, unwittingly, became one of two eminent artists to first assist firearms and ammunition companies with advertising in this country. (The other was George Catlin, of Indian portraiture fame, who in midcentury produced six illustrations for Colonel Samuel Colt and his matchless handgun.)

An Anxious Moment (1880), painted for a doctor in Springfield, New York, is probably the only Tait canvas to depict an Adirondack guide boat, a watercraft indigenous to the region. The good doctor paid $300 for the painting, plus $35 for the frame.

The painting used for the poster show a buck swimming through a marsh, with three startled ducks rising into a mist. It is a simple but effective image, suggestive of the hunting camp art by painters like Frederic Remington which began to flourish later, in the 1890s.

In 1869, at age 50, Tait’s productivity waned miserably. He painted only 16 canvases that year, and was often uncomfortable, in poor health and frustrated by the inroads which had been made by summer tourists into the Raquette Lake region of his beloved Adirondacks. His old companion guides became more difficult to obtain, as other artists and Gilded-Age visitors began to request their services. Lodges were overcrowded; unoccupied camps became harder to find. Much of this was the consequence of a best-selling book published by a clergyman, William Murray, Adventures in the Wilderness, which amounted to a glorification of Adirondack camp life. Tait, at last, became disgusted.

In the summer of 1870, Tait chose to move farther northward into the Adirondack wilderness, to Long Lake. Using a boarding house as a base, he wandered restlessly, searching for that synthesis of land, tranquility and spirit which he had cherished in earlier summers. He found it, finally, at South Pond, a nearby but isolated area of solitude and superb fishing.

Tait went to work and built a small lodge at water’s edge, as a retreat for the summer of 1871. Here, the following year, he began to recover his vigor, and soon he was functioning again as “one of the most skilled sportsmen on these waters,” in the words of a visiting journalist.

Tait stayed in his rustic, lakeside quarters late into October, fly fishing and float-hunting for deer. He was struggling now with a new painting, Autumn Morning, which was to become, at three by six feet, the largest canvas of his career. Back in New York City, he worked all winter on the painting, which was completed in time for the annual spring exhibition by the National Academy of Design.

Mallard and Canvasback appeared as a hand-colored lithograph in 1854.

It is a luminous landscape, crystalline and calm, with a level of grandeur that is rare for Tait. Some critics consider it his finest piece.

Tait sensed the accomplishment of Autumn Morning. For the exhibition, he marked it with the lofty price of $1,250.

Soon after the exhibition Tait lost his wife, his companion for 34 years, in an unexpected death. Bereaved, he made a short trip to England, returned, remarried and purchased a spread of 100 acres on Long Lake. In exchange for a painting, the New York architect J. Cleveland Cady designed a house for the site. (It has now perished, but some of Cady’s other work survives, including the American Museum of Natural History and the Metropolitan Opera House.)

In the spring of 1874, Tait moved into his new home in the Adirondacks to live year-round. He moved, in part, to improve his failing health, in part to escape certain anxieties associated with life in bustling Manhattan, not the least of which was the concern among artists that new European painters were ominously encroaching upon their home market.

Tait painted more than 100 canvases of white-tailed deer. Almost all of these paintings, such as Autumn Morning, Raquette Lake (1872), show the animals in and around water.

For the next three years, Tait lived happily, if marginally, shipping paintings to dealers, exhibitions and on infrequent occasions to private patrons, including Cornelius Vanderbilt. He also did a limited amount of advertising work. Besides the Laflin & Rand commission for “Orange Sporting Powder,” Tait completed a painting of dogs rollicking in a wine cellar, among bottles, straw and a number of cases of Piper-Heidsieck champagne, for which he received $500 from Frank Osborne, the New York importer of Piper-Heidsieck.

But Tait was not solvent. He was selling an insufficient average of two dozen paintings annually, applying some of the proceeds against old debts. In 1881 the 60-year-old artist put his Adirondack home and furnishings on the market and returned sadly to Manhattan, entering a period, in contrast to his first remarkable decades, of hard times for the nation’s sporting painters.

American tastes in art were changing. Economically, popular national art was losing ground to new styles from Munich and Paris, and painters in Tait’s vein were forced, sometimes abruptly, to start counting pennies. The landscape, sporting and genre market, at least within New York City, had become badly depressed.

To support himself. Tait worked for a time as an art instructor. It suited him badly, and in any case seemed to help little. He was still forced to trade off some of his painting for such essentials as rent, shoes and household goods.

Distressed, he finally made two astute moves to regain his financial security. First, he switched almost exclusively to the painting of domestic as opposed to wild animals, which he knew would appeal to a wide rural audience; and second, he began to market his work outside of New York City, in less cosmopolitan areas where attitude toward art were unsophisticated. From an aesthetic viewpoint, it was a disappointing transition. Thereafter, his work became predictable, repetitive and pedestrian. But he at least remained productive and no longer had to barter his works for objects of clothing.

Distressed, he finally made two astute moves to regain his financial security. First, he switched almost exclusively to the painting of domestic as opposed to wild animals, which he knew would appeal to a wide rural audience; and second, he began to market his work outside of New York City, in less cosmopolitan areas where attitude toward art were unsophisticated. From an aesthetic viewpoint, it was a disappointing transition. Thereafter, his work became predictable, repetitive and pedestrian. But he at least remained productive and no longer had to barter his works for objects of clothing.

In August of 1888 Tait packed together his family and made a final visit to the Adirondacks. He painted his last Adirondack scene, a canvas depicting deer along Raquette Lake, and checked out of the hotel in time to escape the hard mountain winter, signing the register, “Going home.” Tait died on April 28, 1905, in New York.

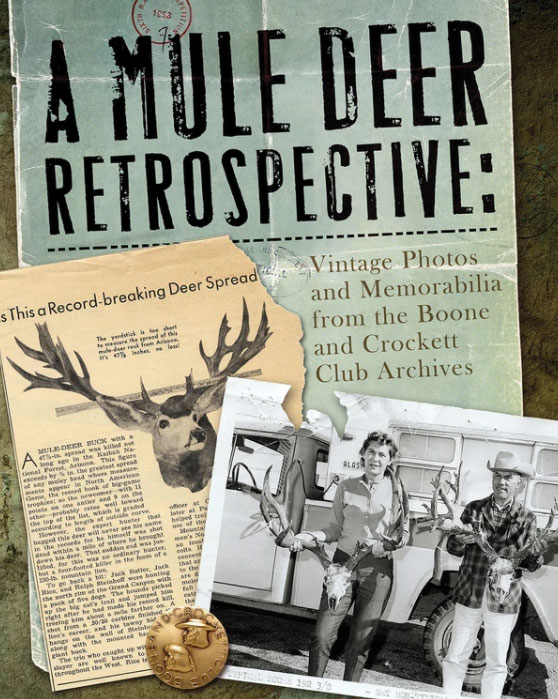

Sportsmen with an eye for the good ol’ days of big game hunting will delight in B&C’s visually stunning book focusing on the iconic mule deer of the West with hundreds of vintage photographs and score charts. Also included are chapters about the status of mule deer, the history of the Kaibab Plateau, women deer hunters, and detailed accounts of dozens of noteworthy mule deer trophies recognized by B&C. No one can deny that the Golden Era of mule deer hunting happened decades ago with nearly 80 percent of the top 50 mule deer recognized by the Boone and Crockett Club being taken before 1976—some taken as far back as the 1800s. With the vast amount of photographs, entertaining correspondence, and historical trophy data, A Mule Deer Retrospective will not disappoint! Buy Now

Sportsmen with an eye for the good ol’ days of big game hunting will delight in B&C’s visually stunning book focusing on the iconic mule deer of the West with hundreds of vintage photographs and score charts. Also included are chapters about the status of mule deer, the history of the Kaibab Plateau, women deer hunters, and detailed accounts of dozens of noteworthy mule deer trophies recognized by B&C. No one can deny that the Golden Era of mule deer hunting happened decades ago with nearly 80 percent of the top 50 mule deer recognized by the Boone and Crockett Club being taken before 1976—some taken as far back as the 1800s. With the vast amount of photographs, entertaining correspondence, and historical trophy data, A Mule Deer Retrospective will not disappoint! Buy Now