A. B. Frost’s paintings captured all the tenseness & humor of sporting situations while retaining the natural characteristics of the hunter & the hunted. Because of the artist’s familiarity with human nature, his love for the sport and the creatures of the field, the storytelling quality of his work has never quite been equaled.

In the history of art, the years between 1880 and 1920 have become known as the “Golden Age of American Illustration;” among the spheres of illustration to hit zenith in those years was the sport scene, which was a particularly popular part of periodicals; and the man recognized during his lifetime as well as today by most authorities and collectors of sports scenes as the outstanding sporting artist of the Golden Age is Arthur Burdett Frost. Frost’s prodigious output as an artist covered many fields, but his sporting pictures, particularly those of men with guns and hunting dogs, are among his most noteworthy works. His “Shooting Pictures” portfolio, a set of twelve lithographs in color of various hunting scenes involving upland game and shorebirds —grouse, woodcock, quail, rabbits, ducks, rail, prairie chickens, snipe — was published in 1895 by Charles Scribner’s Sons and established A.B. Frost without question as America’s premier sporting artist. Prints from “Shooting Pictures” are eagerly sought and valuable collector ‘s items today, as are prints from other of Frost’s sporting groups.

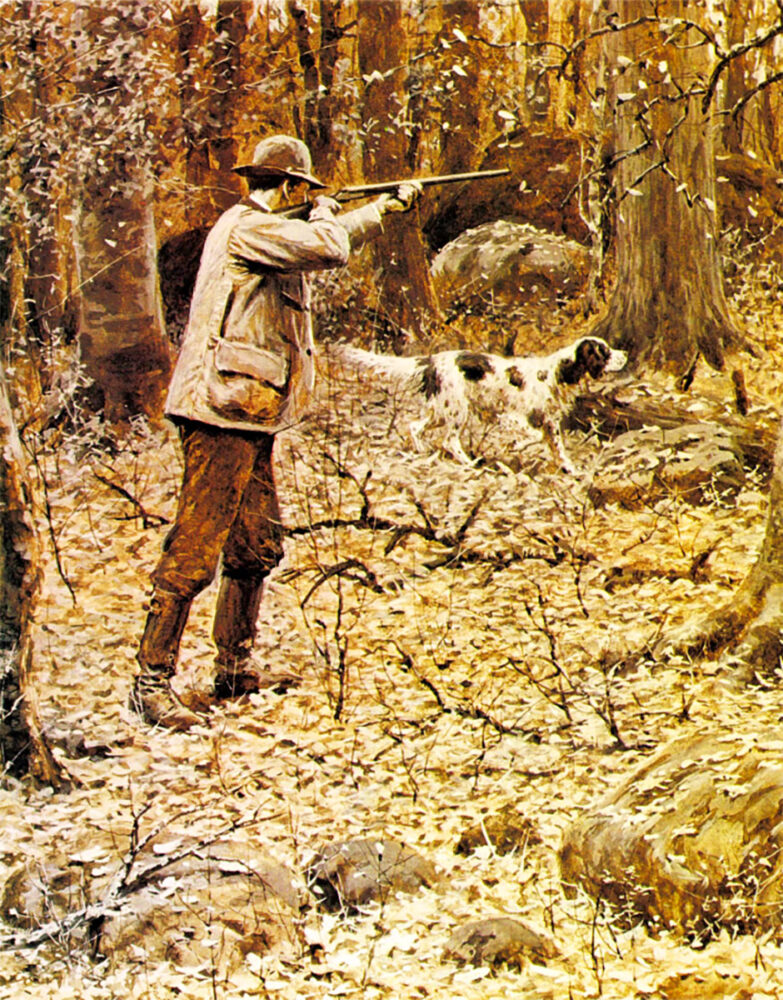

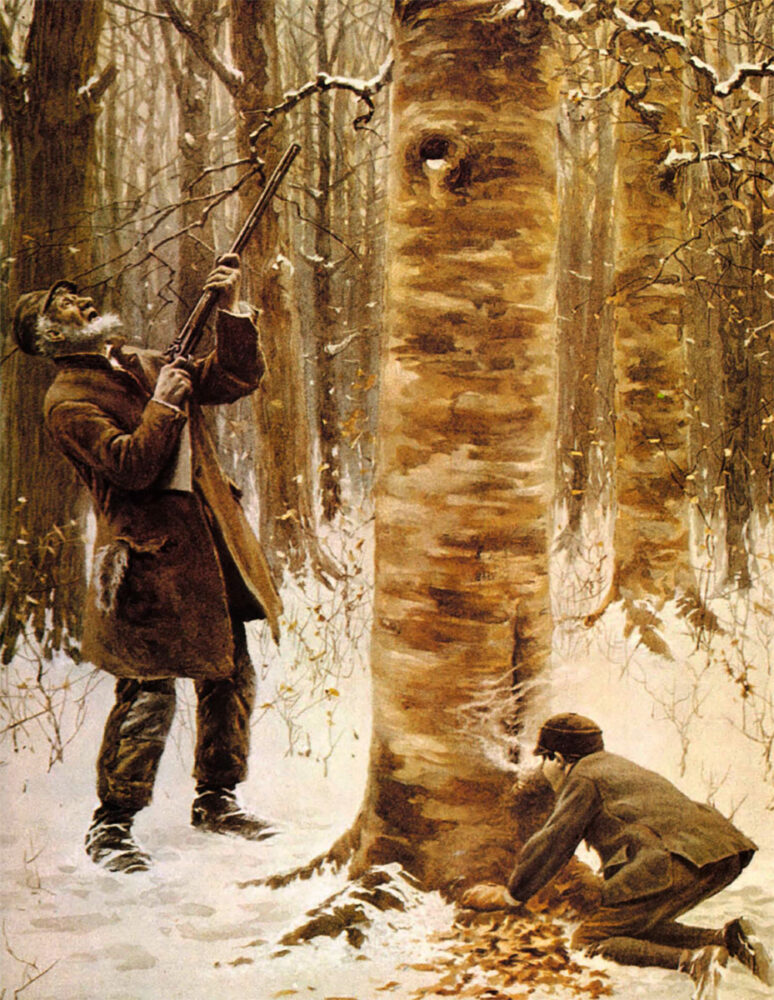

Grouse Hunting, 1916. This illustration

appeared as one of a series of bird hunting scenes by Frost in the November 1916 issue of Scribner’s magazine .

Members of the sporting community, who began calling Frost “The Sportsman’s Artist” in the last decade of the nineteenth century because of the intense pleasure they derived from viewing his scenes, agreed that some artists excelled in depicting mood, some detail and some authenticity of sporting scenes, but that A. B. Frost, himself an ardent sportsman, exceeded the lot in depicting all three. Whether the artist was capturing the instant a quail was flushed by a pointer, or ducks were circling as they made ready to “stool in” over a hunter’s decoys, or a deer was emerging from a thicket, or a rabbit hopping through the snow, or a fish surfacing, or a moose or elk falling, the scene perfectly translated to the viewer the actions and reactions of the animals and the feelings of suspense and excitement of the picture’s human subjects.

One of Frost’s contemporaries wrote that he’d heard a man enthusiastically describe “the look on the face” of a hunter in a Frost picture when, actually, only the subject’s back appeared. Another claimed, “No one can put more expression in an animal — including the creature’s legs — than A. B. Frost. He manages to capture all the tenseness and all the humor of sporting situations, without changing the natural characteristics of hunter or hunted.” Indeed, Frost’s sportsmen and his beasts were often comical, but they were never caricatures. He treated his characters with a directness and honesty which showed his sympathetic understanding of them and his intimate knowledge of nature.

Pen and ink self-portrait.

Frost’s pictures have an extraordinary storytelling quality, but he did not have to have actual hunting action in his scenes to portray a fine, warm hunting tale. Two of his pictures, one a hunter and his dog starting out for a day’s sport and the other the same pair returning at day’s end, tell volumes even to the non-hunter. In the first, the man and dog are quick and bright and full of pep and anticipation; in the second, the two are tired but contented after a long, satisfying day in the woods — with Frost telling all this in a few strokes by the way the hunter’s foot springs from the ground or drags, the angle of his hat on his head and the like; and by the “expression” of the dog’s body, from the carriage of his head to the droop in his tail.

Joel Chandler Harris appreciated the fact that enjoyment of Frost’s pictures did not involve any knowledge whatsoever of the technique of art. Harris thought that one of the qualities which gave the artist’s work “a color and pungent flavor of its own” was flits persistent and ever-present humor — the humor that makes first cousins of all mankind.” Harris wrote the introduction to Frost’s” A Book of Drawings,” published in 1904, and in it commented on the artist’s great gift for telling a hunting story, as illustrated by the several hunting prints included in the “Drawings”:

“Brer Rabbit,” 1892.

From this early pencil sketch evolved the unforgettable characters of Joel Chandler Harris’ Uncle Remus andHis Friends.

“For him (Frost) life and its activities have a perpetual charm. Human nature appeals to him in all its manifold ramifications and possibilities; he would pluck the heart out of the mystery of character and individuality. He is familiar with the creatures of wood and field, and he carries with him that love of sport that good men and healthy boys have in common; but even when the hunt is at its height-when the dogs are in full cry, and the horses running free-he is interested in the fate of the cautious gentleman, who, too timid to face the fence, has dismounted to lower the bars, and, as his horse takes to his heels, comes face to face with Brother Bull, whose good humor is not proof against the irritation of a red coat. The situation is dramatic and full of humor. We feel that the frightened gentleman will live to hunt another day, for Brother Bull is not as angry as he might be; he has come forward to investigate, and by the time he shakes his head preparatory to using his horns, the hunter will have scaled the bars.”

Arthur Burdett Frost grew up as a member of a family with a fine reputation but little money. His father, Harvard-educated Professor John Frost, had spent his early maturity as a schoolteacher, but by the time of Arthur’s birth, in Philadelphia on January 17, 1851, had been for some years devoting his time exclusively to writing histories and biographies. Professor Frost died before Arthur reached his ninth birthday. The boy was one of ten children but only one of his brothers and one of his sisters survived beyond Arthur’s teenage years. The sister, Sarah Annie, wrote a few books, one of which Arthur illustrated. The brother, Charles, became an author under the pseudonym C. S. Ribbler, as well as owner of Godey’s Ladies Book; he wrote the jingles for A. B.’s first book of drawings, Stuff & Nonsense.

Young Arthur Frost, from age 15, was thrown on his own resources. He worked at engraving and lithographing, and, after job hours, studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. He later studied for about a year in London, but for the most part he was self-taught.

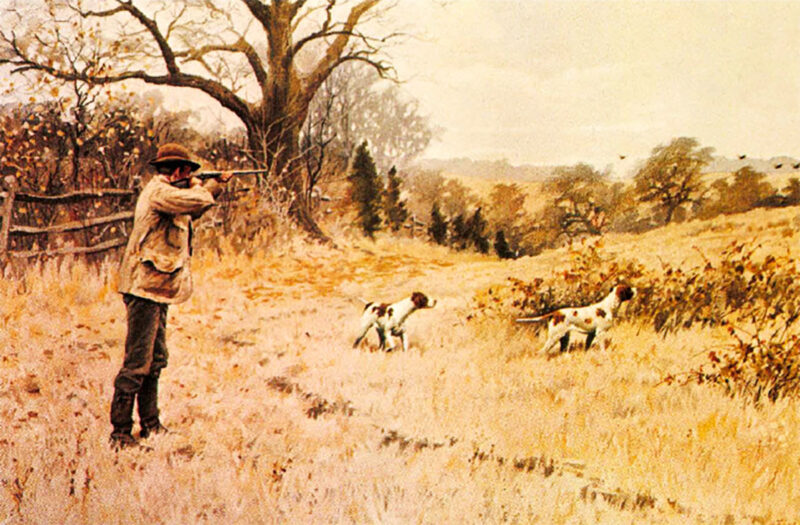

“Quail – a Covey Rise,” 1895. This colored lithograph is one of a set of twelve sporting prints published in Frost’s first portfolio, “Shooting Pictures.”

In 1874 Frost, at 23 still a struggling, poorly paid lithographer, had a stroke of luck. Humorist Charles Heber Clarke, who wrote under the pseudonym Max Adeler, suggested the young man “do a few sketches” for his forthcoming book, Out of the Hurly Burly. The book was published with 379 illustrations, almost all of them by Frost. It enjoyed immediate success, and the review of it in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin included these remarks:

“The illustrations are much the best that have ever been given in any American book of humor. There are nearly four hundred of them, most of which were designed by Mr. Arthur B. Frost, a young man whose genius has had its first good chance in this work, and who is sure to become famous as a designer, especially in the line of the grotesque and comical.”

The Wilmington Commercial said Frost’s illustrations were “excellent in design and execution” and that the artist’s success was “such as to put him at once in the foremost rank of American humorous artists.”

“Good Luck,”1903. Included in Frost’s second published portfolio, this painting was one of a pair of duck hunting scenes entitled “Good Luck” and “Bad Luck.”

In 1875 Frost went to New York City and secured employment on the New York Graphic, and the next year began to work in the studios of Harper and Brothers. On the strength of the success of Out of the Hurly Burly, he was sought as a book illustrator and began the climb to the top in that field. Through the years, he illustrated close to 100 books, many of them by famous authors, including Lewis Carroll, Charles Dickens, Joel Chandler Harris, Mark Twain, Theodore Roosevelt, Frank Stockton and William Thackeray.

Frost’s drawings for Joel Chandler Harris’s much-loved Uncle Remus — Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox, Tar-Baby, Mr. Possum, Mr. Bear, Mr. Bull-Frog, Mr. Wolf, Mr. Buzzard, Miss Cow, Mr. Terrapin, Mr. Jack Sparrow — are among the most famous of the artist’s book illustrations. He was drawing illustrations for Harris’s short stories in Century magazine as early as 1884, but his first Uncle Remus characters were not drawn until 1892; his last Uncle Remus drawings were made a quarter of a century later. Joel Chandler Harris dedicated the 1895 revised edition of the book, which carried over 100 Frost drawings, to the illustrator. In the dedication the author said he expected the new edition to be more popular than the old one, and continued, addressing the artist:

“Do you know why? Because you have taken it under your hand and made it yours. Because you have breathed the breath of life into these amiable brethren of wood and field. Because, by a stroke here and a touch there, you have conveyed into their quaint antics the illumination of your own inimitable humor, which is as true to our sun and soil as it is to the spirit and essence of the matter set forth. The book was mine, but now it is yours, both sap and pith.”

From the beginning of Frost’s career as an illustrator he was known as “a master draughtsman.” His drawings for Out of the Hurly Burly in 1874 were done with pen and ink on wood; they were then cut by the engraver and printing was done from the original wood block. By the time he was drawing the Uncle Remus characters the tedious woodcut process had been superseded by much improved methods, with resultant improvement in his pen-and-ink illustrations as finally printed.

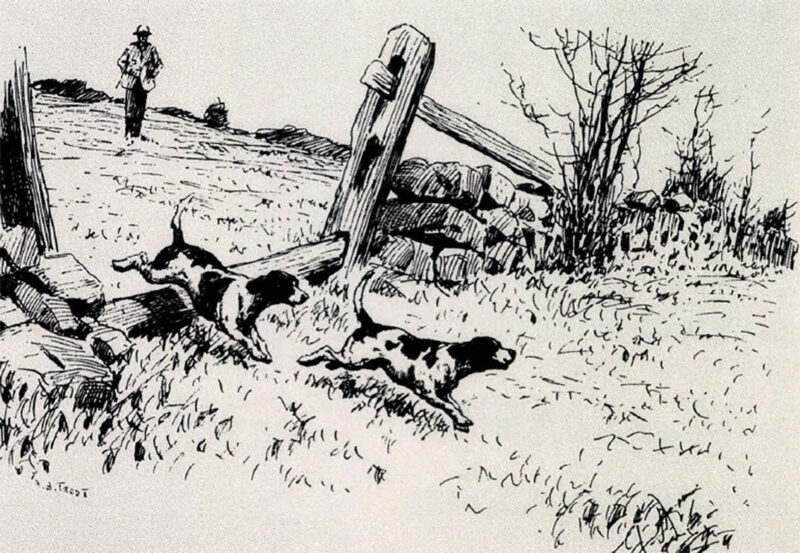

Pen and ink hunting scene.

Frost did his first work in oil in 1884, and in less than a year was painting striking oil canvases which were used as magazine illustrations. His illustrations, regardless of the medium he was using, were in increasing demand for Harper’s Magazine, Scribner’s, Collier’s and other periodicals. His sports pictures-hunting, fishing, camping, hiking, bicycling, baseball, ice-skating and other out-of-doors activities-all had strikingly appropriate and effective, and often quite beautiful, landscape backgrounds. In some of his pictures of hunters in pursuit of waterfowl, for instance, great stretches of misty marsh under deep, cloudy skies make the landscape a smoothly natural part of the sporting subject.

In 1883, A. B. Frost, in addition to filling three books and a number of magazine illustration assignments, was holding down a staff job at Harper’s. His path crossed that of pretty Emily Louise Phillips, the daughter of a wealthy Philadelphia industrialist, who had studied art in Germany and was currently working part-time filling spot illustration assignments for Harper’s. In October, 1883, 32-year-old Arthur and 31-year-old Emily married and soon set up housekeeping in Huntington, Long Island, whence they commuted to New York City.

The couple had two sons, Arthur Burdett, Jr., born in December, 1887, and John, born early in 1890. In the summer after John’s birth, the Frosts decided they needed larger quarters and bought a 120-acre country estate which had a huge and stately, but somewhat rundown, main house, at Convent Station, New Jersey, in the vicinity of Morristown. A. B. Frost named the new homestead “Moneysunk,” and plunged into an enormous output of illustrations to pay for the major repairs the place required.

“Smoking Him Out,” 1903. This painting was included in Scribner’s second portfolio of Frost’s sporting prints entitled “A Day’s Shooting.”

Frost said many years later that the 16 years the family lived at Moneysunk were the happiest of their lives. As Frost’s financial pressures eased up, and as the boys grew, the artist began to spend a lot of time teaching them to draw and paint. He was delighted that both showed great talent and that they accepted his instruction with enthusiasm while awaiting the proper time for more formal art lessons. The “Master of Moneysunk” was far less successful in his farming efforts; his “total lack of prowess with field, seed and plow” did, however, come through his pen and brush into some funny rural scenes.

In the 1890s interest in the game of golf was spreading rapidly throughout the United States, and in 1895 a Golf Club was established just a 15-minute walk from Moneysunk. A. B. Frost took up the new game with zeal, and the countryside was soon ringing with amusing tales about the red-headed, red-bearded artist’s outbursts of temper and capers on the golf course. Soon after Frost started playing the game, he began drawing humorous golf pictures for Harper’s. They were so well received that he and one of his golf partners, W. G. Van T. Sutphen, collaborated on a book, The Golfer’S Alphabet, for which Sutphen wrote a jingle and Frost drew a golf sketch representing each letter of the alphabet. The book, published by Harper and Brothers in both New York and London, was hilariously funny and enduringly successful. Frost kept on drawing golf sketches, but he continued to produce his favorite hunting and fishing scenes, and other sports pictures as well.

In the summer of 1906 Frost sold the estate at Convent Station and the family sailed for Europe. A. B. had been working very hard and saving money for some time with the idea that he and Emily would take Arthur, Jr., and John abroad to study. The boys, by then 18 and 16 years old, had studied at art schools in New York and under private tutors prior to that time.

By September the Frosts were settled in Paris. Arthur and John shared a studio and Arthur, Jr., established a small one for himself. Both boys were enrolled in the Academie Julian. The elder Frost had planned to do some “serious” painting, but he put that off and concerned himself with filling assignments sent from America. In 1907 the family established a country home in a picturesque little “artists’ town” a few hours from Paris by train. There A. B. painted some exquisite water-color landscape studies, but he wasn’t very pleased with them. “I paint,” he wrote from France, “but not with the idea of ever making a painter; I paint for fun.”

A. B. was delighted with the splendid work John was doing, but quite displeased that Arthur, Jr., was falling under the influence of the Modernists. A. B. Frost could not understand how a true artist could abandon realism in favor of forms created by color-and light-emphasis and far removed from nature. He was distressed that his son was turning away from his early academic training.

In the spring of 1911, Frost’s displeasure with his older son’s art faded into the background when the family was hit with dreadful news: both 23-year-old Arthur, Jr., and 21-year-old John, who’d been thought to have colds, actually had tuberculosis.

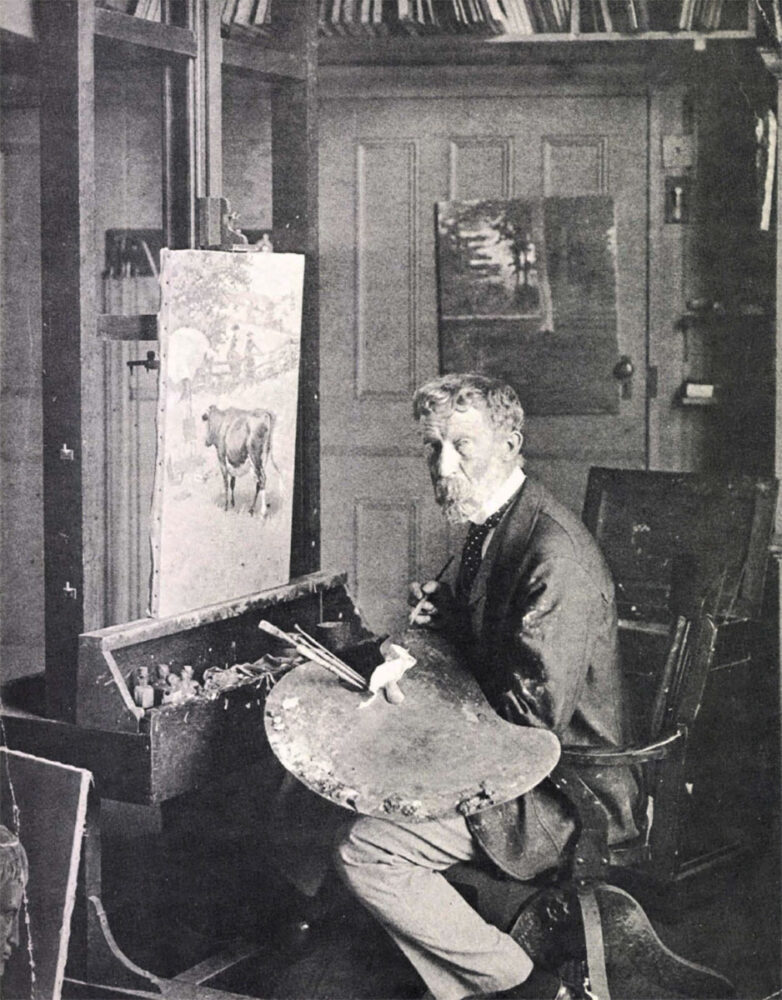

Arthur Burdette Frost in his studio, 1904. The painting on the easel is entitled “The Horrid Thing.”

The Frosts moved to Davos-Platz, Switzerland, where, on the advice of Paris specialists, the young men were installed in a world-famous sanatorium. A. B. and Emily moved into the Hotel National in Davos-Platz-and the artist gave thanks for well-paying assignments from America. “Serious painting for fun” forgotten, he worked at illustrating with redoubled effort. After long stays in the sanatorium the younger Frosts were dismissed, and A. B. made ready to return to America with his family Arthur, Jr., however, was determined to remain in Paris; he attained a degree of success and was among the first Americans to experiment with scientific color theories. The other three Frosts sailed for home in May, 1914.

The Frosts settled in Wayne, Pennsylvania, and, after a time, Arthur, Jr., returned to America and established a studio in New York City. He died there — of “Bohemian dissipation,” according to one account — in December, 1917, four days before his 30th birthday. For a year, A. B. Frost was devastated with grief, and he never completely recovered from Arthur, Jr.’s death.

It was largely Frost’s pride in his son John, who had a fine career as an artist, that renewed his spirits and made him “wild to work again.” In December, 1919, John’s doctor told him he must live in the Southwest, and he moved, along with his parents, to California. A. B. and Emily settled down in Pasadena for the rest of their lives. John acquired a lovely wife, a reputation as the finest landscape painter on the West Coast and, later, recognition as a first-rate sporting artist. He lived to be only 47, but his father was spared that grief.

Arthur Burdett Frost, aged 77, died in his sleep June 22, 1928, at his Pasadena home, and was buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia. Emily, who had been close by his side in happiness and tragedy, survived him less than six months.

Newspapers from coast to coast sang the praises of A. B. Frost as painter, illustrator, humorist; and some referred to him with that old appellation that had always pleased him most: “The Sportsman’s Artist.”

Editor’s Note: This article, authored by Peggy Robbins, originally appeared in the Premier Issue of Sporting Classics in 1981.

Considered by many as the world’s foremost sporting artist, Eldridge Hardie has been painting hunters and anglers on the water and in the field for more than three decades.

Considered by many as the world’s foremost sporting artist, Eldridge Hardie has been painting hunters and anglers on the water and in the field for more than three decades.

Now, in his new large format, 12 x 10 inch book, The Sporting Art of Eldridge Hardie, the gifted artist presents 150 paintings of upland bird hunters, waterfowlers and anglers. Readers will love his detailed depictions of many different breeds of gundogs. Buy Now