I admit, that, like most fox hunters, what attracted me was the excitement of being able to gallop over big fields and jump big fences out in the real world.

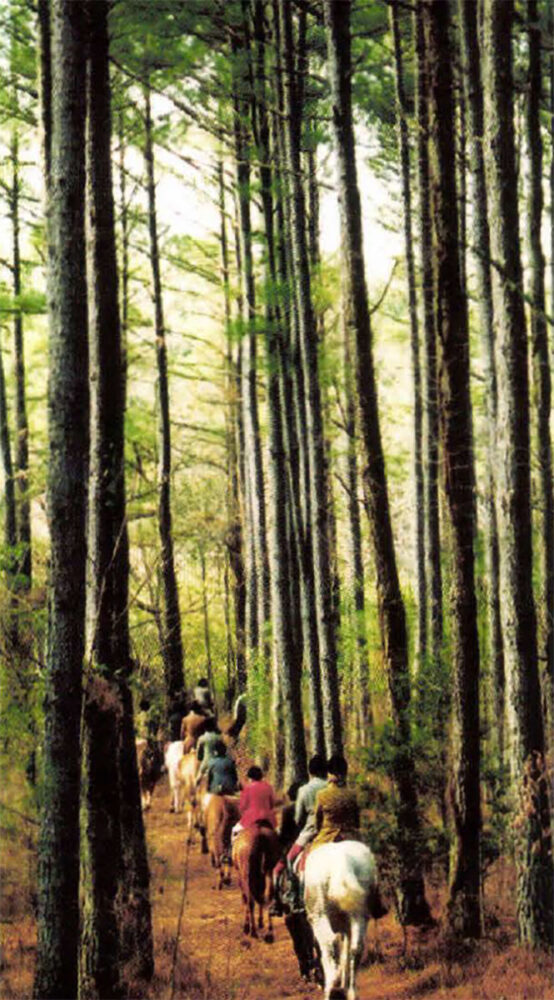

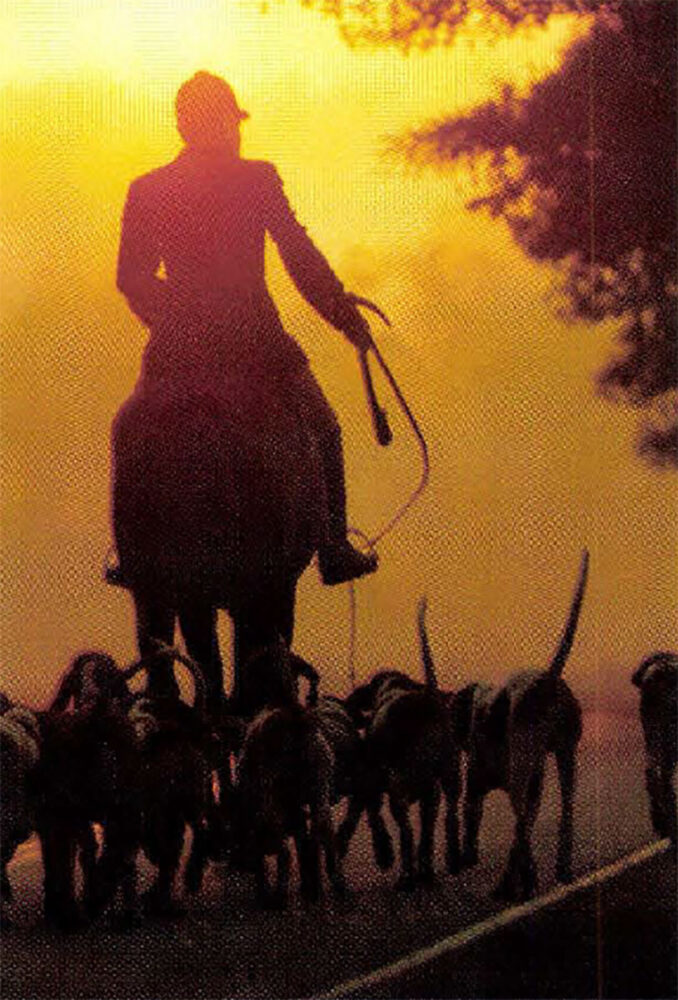

When I dream about horses, as I sometimes do, I often dream about my own horse, a large and touchy palomino, on the one day in ten years of fox hunting when everything went right. On that October day, the red-tailed hawks whistled overhead, the soft early sunlight angled through the mist rising from the woods, the autumn smells of sumac and fallen leaves and damp earth filled the air, and my horse was the palomino Pegasus. He soared over every fence as if he had wings. He never pulled at the bit or crowded the horses in front of him or embarrassed me by running wildly past the master as all the field looked on. He didn’t fidget and paw and buck at a halt and force me to walk him nervously around in a circle. He didn’t stop suddenly at a jump and send me soaring over the fence as if I had wings. He stood neatly to the side when the huntsman with his red coat and the hounds with their heedlessness came dashing toward us on a narrow path in the woods, not blundering into their way at the last second owing to that perverse quirk of human and equine psychology that all too often leads us somehow to signal, and horses somehow to heed, the one thing we are trying with all our conscious might to tell them not to do. He was, in short, the perfect horse on the perfect day.

When I dream about horses, as I sometimes do, I often dream about my own horse, a large and touchy palomino, on the one day in ten years of fox hunting when everything went right. On that October day, the red-tailed hawks whistled overhead, the soft early sunlight angled through the mist rising from the woods, the autumn smells of sumac and fallen leaves and damp earth filled the air, and my horse was the palomino Pegasus. He soared over every fence as if he had wings. He never pulled at the bit or crowded the horses in front of him or embarrassed me by running wildly past the master as all the field looked on. He didn’t fidget and paw and buck at a halt and force me to walk him nervously around in a circle. He didn’t stop suddenly at a jump and send me soaring over the fence as if I had wings. He stood neatly to the side when the huntsman with his red coat and the hounds with their heedlessness came dashing toward us on a narrow path in the woods, not blundering into their way at the last second owing to that perverse quirk of human and equine psychology that all too often leads us somehow to signal, and horses somehow to heed, the one thing we are trying with all our conscious might to tell them not to do. He was, in short, the perfect horse on the perfect day.

And then he threw a shoe, and I took him home. I have not taken a survey among fox hunters, but I think one (almost) perfect day in ten years is well above the mean.

There are few sports in which image and reality are as far apart as they are in fox hunting. The literature of fox hunting is all noisy insiders’ bluster; the public spectacle is all anachronism and pomp; the politics (here in America less so, but ineluctably in animal-loving and class-resentful Britain) is all about privilege and cruelty. The reality is none of these things. Fox hunting is essentially an inner struggle against dashed hopes. It is an elemental experience for horse and human being alike. For the coddled horse it is a day of behaving like the herd animal that a horse fundamentally is — a day of milling about with a few dozen other horses and then (what horses do best), stampeding. For the coddled human being, used to controlling at least somethings in his modem life, it is a raw exposure to all the powers of fate and misadventure that used to constitute human existence and for which we were not always the worse.

I don’t mean danger, necessarily, though there is some of that. What I really mean is things not going right. Things never go light in fox hunting. I could write an epic of dashed hopes on the subject of horseshoes alone. And as for getting over fences, one lifetime would scarcely be enough to record all the heartbreak that fences represent.

To outsiders, fox hunting probably seems incomprehensible, or at least very odd. There are 168 organized fox hunts in the United States, nearly all supported by their dues-paying members, many of which hire a professional huntsman to take care of, train and hunt the hounds two or three days a week during the season, which runs from fall to early spring. Its elitist image notwithstanding, even in 18th century England hunting was quirkily egalitarian: farmers and dukes rode side by side, and the Prince Regent could tell a tall but not actually implausible tale of having gotten into a scuffle on the hunt field with a Brighton butcher who had “rode slap over my favorite bitch, Ruby.”

In some ways, American hunting in the early 20th century, when it became officially organized with associations and “recognized” hunts, was more English than the English, a way for nouveau riche northern plutocrats and faded-glory southern gentry to burnish their self-styled aristocratic images. But that has all been more or less swept aside, not so much by American democracy as by the American middle-class enthusiasm that is the chief characteristic of most participatory sports these days. The people who were in it for the social cachet have long since found easier ways to make a social statement. In most hunts, well over half the members are women, mirroring the general demographics of equestrian enthusiasm. And hunting is no more expensive than golf or skiing or sailing — other pursuits once exclusively for the idle rich.

About half the foxhound packs in North America hunt coyotes, which are rapidly taking over the habitat of the red fox. In American hunting, it is far and away the exception for hounds actually to catch and kill a fox (there are U.S. fox hunts that have hunted for thirty years without making a kill), and foxhounds almost never catch a coyote (coyotes are faster than hounds, and woe betide any hound that does manage to catch up with a coyote).

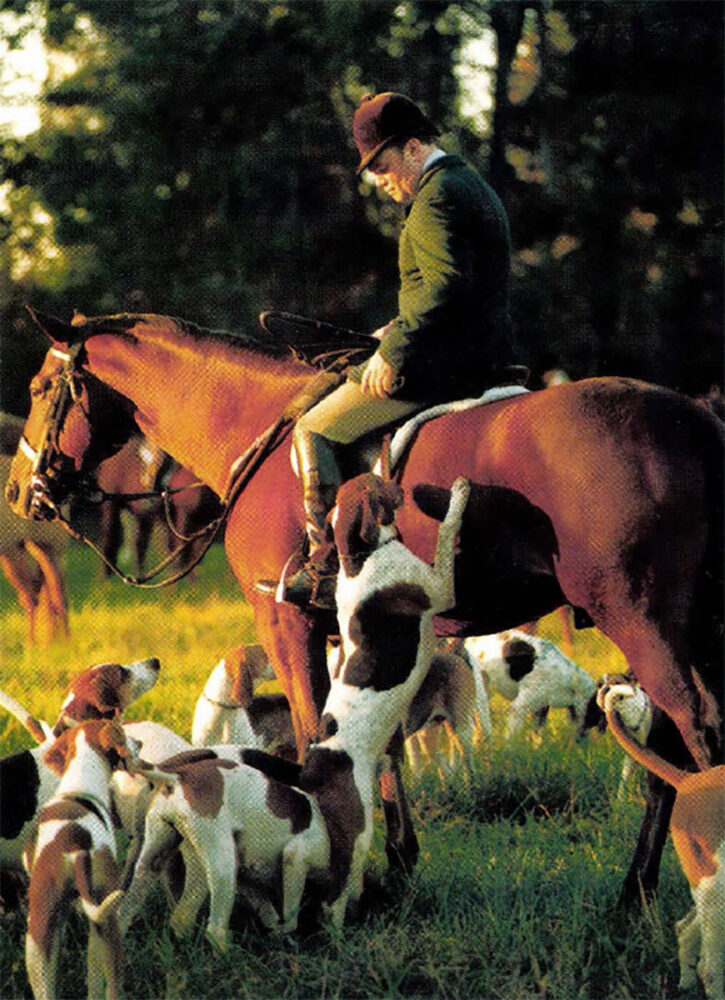

Serious hunters talk about the pleasures of watching hounds work a line of scent and of hearing them “speak,” and they are not talking through their hats. I thought that one woman who rides with my local hunt, a nurse who arranges her shifts in the pediatric intensive-care unit around her hunting schedule, was putting me on when a hound a quarter mile away would speak and she would name him, but I soon discovered that she did in fact know every one of 50 or so hounds both by looks and by sound. Hounds differ not only in looks and sound but in personality, too, and part of why experienced hunters make a point of getting to know the members of the pack as individuals is that some hounds are notably more reliable than others in speaking when they pick up a true scent – and in not going after a false trail, or worst of all, plunging off at high speed after a deer. Yet there is also a sort of almost group consciousness that comes into play in the work of hounds and huntsman: The huntsman calling on his instinctive knowledge of the lay of the land and the habits of foxes and hounds to judge when to call the pack off and where to cast them when they lose the scent; the hounds’ attentive not only to what their own noses are telling them but to the movements and cries of their pack mates.

I admit, though, that, like most fox hunters, what attracted me was the excitement of being able to gallop over big fields and jump big fences out in the real world. Fox hunting is an experience unlike anything available at the Merrymount School of Equitation, where riding around a ring in a horse show is as exciting as it gets. In the ring, with a raked, stone-dust footing and nicely painted standards holding a cross rail that obligingly drops to the ground if your horse’s foot so much as brushes against it, you might, after years of lessons, jump a three-foot-high fence. In hunting, there are four-foot jumps made of the most unforgivingly solid materials in the most awkward of spots: uphill, downhill, into the woods and out, some with extra rails on top to keep the cows in, some with a two-foot drop down a bank on the landing side. The fences that one jumps in the hunting field these days are usually modified for the purpose of jumping, but even so, no two are alike in how they need to be ridden or in the ways they can cause trouble.

In the old days, fox hunters just followed the hounds wherever they led, and when the horses came to a stone wall or a post-and-rail fence, they jumped at any likely spot. Then came wire fences, which only the borderline suicidal try to jump — horses have a hard time seeing a wire from a distance or judging its position in space, and so the likeliest outcome is that the horse stops short when he reaches the fence. The worst outcome is that he goes ahead and jumps, and misjudges it and catches a foreleg. When a 1000-pound animal trips in midair, a soft landing is not generally possible.

In the old days, fox hunters just followed the hounds wherever they led, and when the horses came to a stone wall or a post-and-rail fence, they jumped at any likely spot. Then came wire fences, which only the borderline suicidal try to jump — horses have a hard time seeing a wire from a distance or judging its position in space, and so the likeliest outcome is that the horse stops short when he reaches the fence. The worst outcome is that he goes ahead and jumps, and misjudges it and catches a foreleg. When a 1000-pound animal trips in midair, a soft landing is not generally possible.

With the coming of wire, fox hunters sought farmers’ permission to build short panels of wooden fencing into the fencelines, the most common pattern being the “coop” — two sloping wooden panels that straddle the wire in the shape of an inverted, rather like an old fashioned chicken coop. Coops are solid and have a clearly visible groundline, which horses require to judge the location and depth of an obstacle properly. With only one jumpable spot per fenceline, riders can’t always follow the hounds in a straight line, but at least the jumps offer a way of getting across at some point.

Before paragliding, bungee jumping, snowboarding and sky surfing, there was fox hunting. The appeal in all cases is much the same. A retired Air Force pilot whom I used to see out hunting many Sundays — a kind and sympathetic man well into his 70s, who took pity on a struggling beginner and would always let me ride right along with him and never said a word even when I was much too close behind him — one day turned to me after we had galloped over three huge coops and said, ”You know, it’s just like flying a fighter plane.” When everything goes right, it is blissful.

When things go wrong, you fall off. There are many ways to do that. The easiest is when your horse decides not to jump and slams on the brakes at the last instant; in accordance with Newton’s First Law of Motion, horse stops but rider does not. I have more than once done a 360-degree airborne flip and landed on my feet during this maneuver — something that a relatively unathletic six-foot, 185-pound man is likely ever to manage in ordinary life. I have been dumped right into a coop this way, but one time I actually cleared the fence, almost landing on my feet on the other side and still holding the reins and I stood there imagining the ignoble scene that was to follow (climb back over the coop, snuggle back into the saddle, have another go at the fence with the same result, repeat until I slink away in shame or am carded off on a stretcher). My horse took a look at me standing there, decided that the fence mustn’t be so bad after all, and leaped over to join me.

When things go wrong, you fall off. There are many ways to do that. The easiest is when your horse decides not to jump and slams on the brakes at the last instant; in accordance with Newton’s First Law of Motion, horse stops but rider does not. I have more than once done a 360-degree airborne flip and landed on my feet during this maneuver — something that a relatively unathletic six-foot, 185-pound man is likely ever to manage in ordinary life. I have been dumped right into a coop this way, but one time I actually cleared the fence, almost landing on my feet on the other side and still holding the reins and I stood there imagining the ignoble scene that was to follow (climb back over the coop, snuggle back into the saddle, have another go at the fence with the same result, repeat until I slink away in shame or am carded off on a stretcher). My horse took a look at me standing there, decided that the fence mustn’t be so bad after all, and leaped over to join me.

Falling off is sometimes dangerous, occasionally fatal and always humiliating. In all my years of taking riding lessons, I was so determined never to fall off that I never did; even the times I should have, my instructor would look over to see the spectacle of a man half out of the saddle defying the force of gravity by clutching his horse’s mane with grim determination.

Then I started hunting, and fell off every other time I went riding. It never really worried me until recently, when the huntsman of one of the local hunts, schooling a horse he had ridden a hundred times, jumped a three-foot-high row of rails that he had jumped hundreds of times (one that I have jumped probably a dozen times), and his horse went one way, and he the other. He ended up rocketing headfirst into a tree and breaking two vertebrae in his neck; he’s now paralyzed from the chest down.

As with all such sports, the whiff of danger is no doubt an element of the appeal, but that’s more danger than I had bargained for. Still, along with the thrill comes an almost Zen dimension to jumping — or at least so I tell myself, for that is probably the only way to cope with day after day of frustration.

As with all such sports, the whiff of danger is no doubt an element of the appeal, but that’s more danger than I had bargained for. Still, along with the thrill comes an almost Zen dimension to jumping — or at least so I tell myself, for that is probably the only way to cope with day after day of frustration.

In the perfect jump the rider feels as if he is the one soaring through space in a parabolic arc; the horse is just something below Swiveling on gimbals, leaving the rider’s balance unaffected. To achieve that result, the rider must maintain his balance with supple knees and ankles — he must be, in effect, independent of the motion of his horse. Yet he can achieve that only by being fully aware of and at one with the horse’s motion — and, indeed, the horse’s anticipation.

The difference between a good jump and a bad jump is like the difference between playing in tune and playing out of tune — even a little bit off is awful. But in hunting there is the compensation, the wonderful compensation, of practicality: jumping over fences has the genuine purpose of getting from here to there. After years of brooding darkly over my imperfect days in the saddle (that is, all of them), I in realism adopted the binary system for rating my jumps. Forget the Olympic 10-point form scale; mine was one or zero — either I made it to the other side and was still in the saddle or I did not. (The time I got over and then immediately fell off into a pond I decided to score as a two.)

Living on a farm, and having seen a good measure of what nature routinely dishes out, I have never taken seriously the claims of cruelty leveled against foxhunting by animal-rights activists. In 10 years of fox hunting, I have seen far more foxes killed on the road by cars than killed by hounds. And foxes, themselves predators, are almost insouciant about being chivied around the woods, often doubling back to lay a confusing trail. I have even seen a hunted fox stopping to hunt mice when he had put a few minutes between himself and the hounds. For the most part, American fox hunting has escaped the wrath of animal lovers, because of its emphasis on the chase over the kill, and because fox hunters are in many rural areas a major force for the preservation of open space and wildlife habitat.

Living on a farm, and having seen a good measure of what nature routinely dishes out, I have never taken seriously the claims of cruelty leveled against foxhunting by animal-rights activists. In 10 years of fox hunting, I have seen far more foxes killed on the road by cars than killed by hounds. And foxes, themselves predators, are almost insouciant about being chivied around the woods, often doubling back to lay a confusing trail. I have even seen a hunted fox stopping to hunt mice when he had put a few minutes between himself and the hounds. For the most part, American fox hunting has escaped the wrath of animal lovers, because of its emphasis on the chase over the kill, and because fox hunters are in many rural areas a major force for the preservation of open space and wildlife habitat.

I worry more about the charge of affected quaintness: fox hunting when you hardly ever kill a fox, and when you haul your horse in a trailer behind a Ford pickup truck to the spot where you can ride, and when you jump panels that have been built into lines of wire fence expressly for the purpose of giving fox hunters a place to jump, is, as charged, contrived and anachronistic. But there is anachronism and anachronism: there is the kind in which you dress up as somebody’s idea of a Renaissance character and go around saying “forsooth” for the tourists, and there is the kind in which you find a real bit of woods and field and submit yourself, if only for a few hours, to the full force of untamed pre-20th century nature. Falling off and breaking your neck is a melodramatic way to make the point. But there are far worse ways to spend an autumn morning than leading your horse across three miles of fields and woods after he’s thrown a shoe. You’d feel like a fool setting out to do that on purpose (“uh, just taking my horse for a walk”), but you never cease being grateful for such mornings.

When scent or hounds or foxes fail to cooperate, there are days when nothing happens and you stand mound for three hours scarcely going anywhere, but there are worse ways, too, to spend a morning than to be sitting on horseback on a hillside while the rest of the world is listening to traffic reports on the radio.

And there is nothing contrived about the work of the hounds in following a scent and the reality of wind and weather and the huntsman’s knowledge of every copse and path and the fact that one’s day is in the lap of fortune. Hunts that spend most of their time puttering through the back yards of 6,000-square-foot mansions are starting to seem like trail rides with dogs, but when the hounds can do their work, they force us to think like dogs and to think like foxes; they turn us from passive spectators and consumers of nature into participants. There are hunters who can hear a hound’s cry and read a whole tale from it, hunters who while the chase is on live through the eyes -or noses – of the hounds. Thoreau wrote of taking “rank hold on life” and living more as the animals do, of spending days fishing and hunting in order to approach nature with an honesty that philosophers and poets “who approach her with expectation” lack.

In this age of spectators, I am not even sure that anyone would understand if fox hunters uttered the truth about what they do and why they do it. The friends of nature say they want wild, untouched nature, but what most people are really after is tame, pretty nature and those who glower darkly out on a wood through the eyes of hounds and foxes are strangely out of keeping with the spirit of a time whose representative nature-goers are those nice extroverts in the L.L. Bean catalogue.

I realized recently that the breezy sportsmen’s reports that pass for the literature of fox hunting are a fraud that hunters perpetrate on one another, a way to pretend that what they do is ordinary, routine, something like golf or woodworking, a pursuit for enthusiasts that is reducible to conventional narrative. A true narrative of the internal experience of a fox hunt would bear no resemblance to external appearance. The formal rituals of hunting — the black and red coats, the polished boots, the saddle-soaped tack, the well-brushed horses that immediately get muddy and disheveled — are there to keep the disguise propped in place. But then it slips, and the truth is out. I will never forget the honor and wonder and delight I felt the day the truth came to one huntsman, a man of decades of experience, a man whose living room is filled with silver trophies and plaques he has won for steeplechase racing, a man who knows hunting and hounds and every fence in the woods. I will never forget the words he shouted as he tumbled from his horse, a sudden burst of fury and truth. “Just one day! Just one day!” He, too, wondered why there can’t be just one day when nothing goes wrong.

I realized recently that the breezy sportsmen’s reports that pass for the literature of fox hunting are a fraud that hunters perpetrate on one another, a way to pretend that what they do is ordinary, routine, something like golf or woodworking, a pursuit for enthusiasts that is reducible to conventional narrative. A true narrative of the internal experience of a fox hunt would bear no resemblance to external appearance. The formal rituals of hunting — the black and red coats, the polished boots, the saddle-soaped tack, the well-brushed horses that immediately get muddy and disheveled — are there to keep the disguise propped in place. But then it slips, and the truth is out. I will never forget the honor and wonder and delight I felt the day the truth came to one huntsman, a man of decades of experience, a man whose living room is filled with silver trophies and plaques he has won for steeplechase racing, a man who knows hunting and hounds and every fence in the woods. I will never forget the words he shouted as he tumbled from his horse, a sudden burst of fury and truth. “Just one day! Just one day!” He, too, wondered why there can’t be just one day when nothing goes wrong.

Copyright 2000 by Stephen Budiansky, as adapted from an article originally published in The Atlantic Monthly.

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski.

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski.

Acclaimed as one of America’s premier dog and sporting artists, Sulkowski shares his personal conversation with the outdoor life in a style of Poetic Realism. Influenced and guided by the hands of the Old Masters, he creates fluid brushstrokes that imbue his canvases with a compelling blend of light, atmosphere, and spatial effects that bring his passion for the sporting life into vivid focus for the viewer. Buy Now