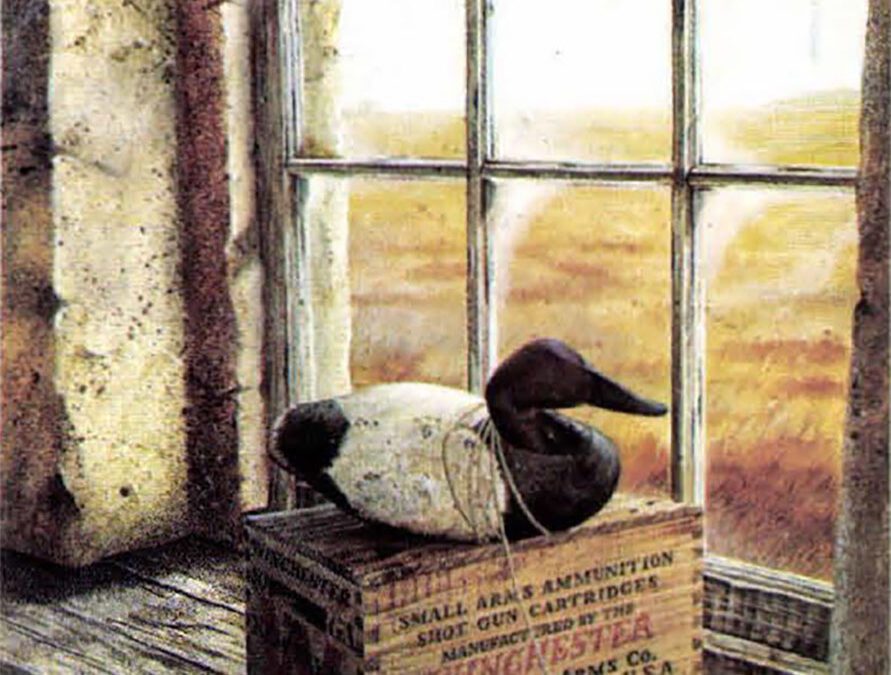

Some collector prints have greatly increased in value in the last few years, but are prints really good investments?

Mockingbird by Ralph McDonald, 1972. Edition of 500, original price $25.

There was something wrong with Ralph McDonald’s mockingbird print, and he couldn’t decide what it was. The year was 1972, and the Tennessee artist had just finished a commissioned painting of the Tennessee state bird, a painting he now claims is the most significant of his career.

Days before he actually began the work he had puzzled over the composition, finally deciding on a rural setting. “I saw an old plow handle sticking up in a patch of blackberries, and there was an old shed in the background. I knew that had to be it, because I could just see a mockingbird lighting on that plow. Everything was there. I had worked hard on it, and I felt I had done a good job,” he said. “But something was missing. It was stiff and seemed to lack feeling.

Bengal Tiger by John Ruthven, 1968. Edition of 1,000, original price $80.

“I went outside and walked around some, and just tried to forget about it. When I came back inside, I knew what it was the first time I looked at it. It was the bird. The bird was just sitting on the plow handle. I threw it out and started over. This time I painted the bird just as he was reaching out to light, and I knew it was a lot better.”

Wolf Pack in Moonlight by Robert Bateman, 1978. Edition of 950, original price $95

A lot better was right. He issued 500 signed and numbered prints, and another 2,000 signed prints were issued bearing the state seal. Today, the signed and numbered prints that sold for $25 in 1972 are bringing over $500 on the secondary market.

No one knows why that print did so well, not even the artist, who claims it was the most significant one of his career. “Of course I didn’t have any idea what it would do, but I knew it was a good piece,” McDonald says. “I wasn’t very well known then, but they sold the print through the state parks. When people bought them and took them into galleries to get them framed I began to get calls from dealers, and things really began to move.”

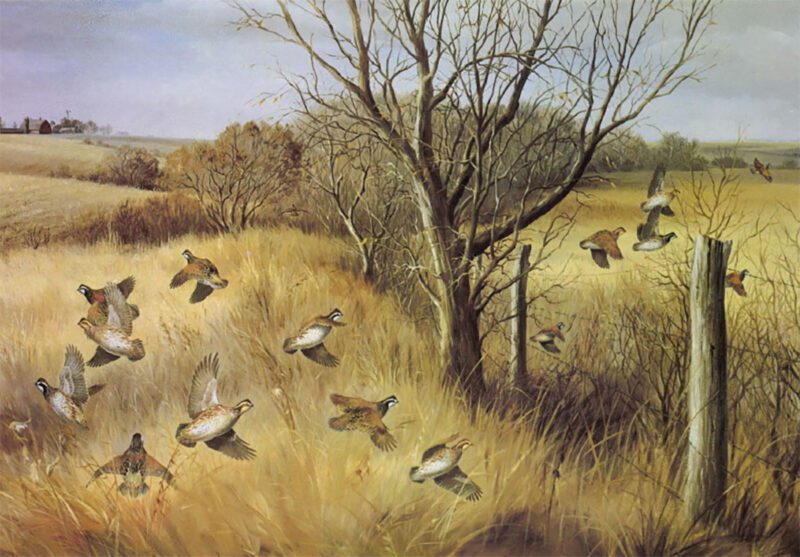

Covey Rise by Maynard Reece, 1977. Edition of 950, original price $150.

How unusual is it for a print to increase in value like that? Not very unusual at all. In fact, there are literally hundreds of prints that have more than doubled in value over their original purchase price, and some have gone up ten, even 20 times over their original purchase price!

Wind River Man by David Wright, 1980. Edition of 1,100, original price $50.

Talk to some, even those in the business, and they will tell you that prints cannot be sold for the kind of prices that are commonly quoted in price guides and certainly not for the secondary prices that some publishers quote for their issue. Others say that’s bull, they have indeed sold prints on the secondary market for the quoted price, and even higher.

Where does the truth lie? It depends on many variables. Prints, like anything else, are worth only as much as someone is willing to pay for them. And that depends on the region of the country, the current demand on that artist’s work, the time you have to sell the print, the availability of the artist’s work on the secondary market, and a thousand other things.

Wood Ducks by Larry Hayden, 1977. Edition of 500, original price $45.

Many people in the print business, even some publishers, are having a hard time believing that their prints are in such demand on the secondary market, and people are willing to pay those prices. It’s almost like some of them are waiting for the bubble to burst, and we’ll all come back to the real world. For those who display poor judgment and bad business sense, perhaps the bubble will burst. For others, the bubble will solidify and they and their artists will continue for years to enjoy one of the better of all worlds, the creation of instant collectables.

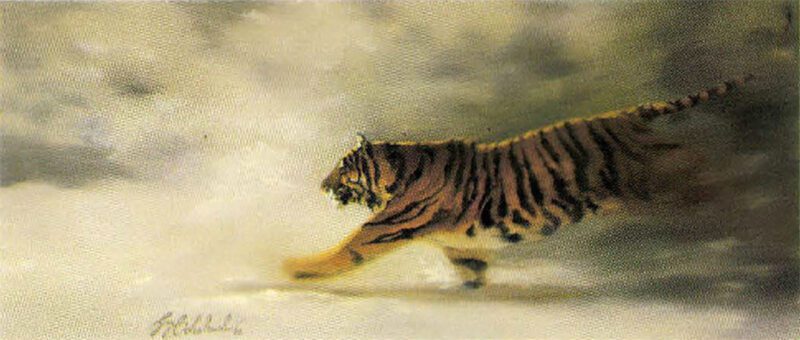

Siberian Chase by Guy Coheleach, 1979. Edition of 850, original price $180. (set)

Wildlife and sporting prints are certainly nothing new. What’s new is the way they are being produced and sold. The old timers, such as Audubon, sold their work as “prints,” but they all had something of themselves in every copy, since they were hand colored. Even after color printing came along the issues were small, and while they certainly weren’t as exclusive as an original the owner of a print would hardly expect to see another one hanging in his neighbor’s house.

Siberian Chase by Guy Coheleach, 1979. Edition of 850, original price $180. (set)

Today most prints are produced in the 500 to 1,000 range, with some editions going as high as 5,000 copies, and some would say there is certainly nothing “limited” about that. But before we condemn modem print issues as too large, let’s consider another factor. In the old days I wonder how many prospective buyers an artist really had. He certainly couldn’t advertise in magazines, because there was no color printing. He was even limited in the number of people he could show them to, travel time and economics being what it was. If he did find people who liked his work, a far lower percentage of everyday folks could afford to pay $25 for a print in 1900 than the percentage today that could come up with $75 or even $125 for something they wanted.

Eagle & Osprey by Ray Harm, 1964. Edition of 500, original price $75.

For every true prospect an artist had in 1920, there would be 50 today, given modem society’s better education and greater appreciation of art, not to mention today’s wide option for advertising that enables a publisher to reach literally thousands of prospective buyers.

Many are aware of the phenomenal increase in the values of duck stamp prints, such as the 1972-73 print of Cinnamon Teal by Maynard Reece that sold originally for $75 and is now bringing $4,500 in just 10 years! Of course, this much increase is unusual even for this series. This is a subject we can address in another article, as they seem to be in a class by themselves.

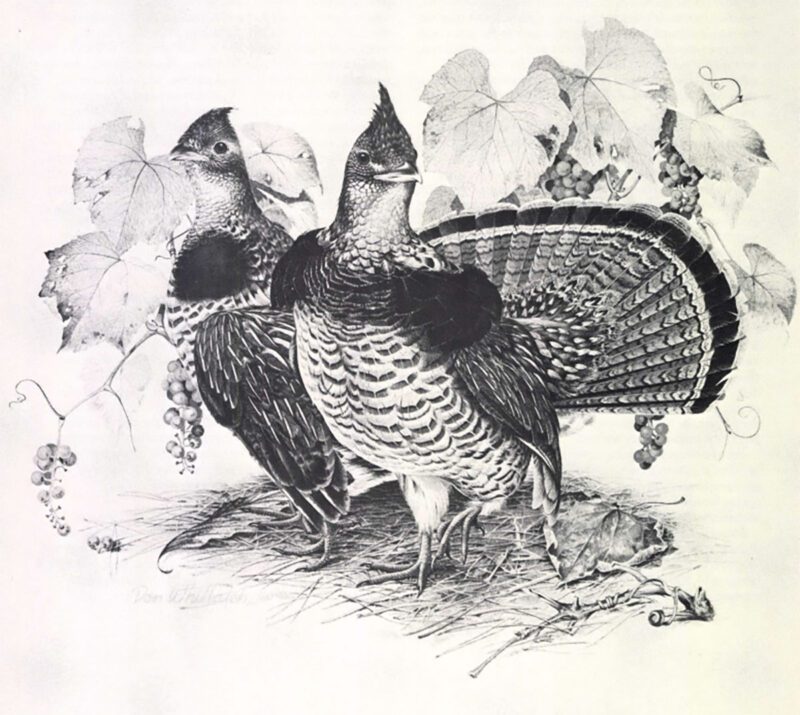

Ruffed Grouse by Don Whitlatch, 1970. Edition of 1,500, signed and numbered, $30.

Then there are the earlier artists, such as A. B. Frost, and Mark Catesby, who sold his prints as a set in the 1720s called “A Natural History of the Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands.” This set, which sold then for less than $50, will bring $60,000 today in good condition, if you can find them. But the all-time champ would have to be John James Audubon, who sold his set of prints in the 1830s for $1,000, which was a great amount of money back then even if they were hand colored. Today, if you managed to find every one of the 435 prints in the set, the total cost would be over a half million dollars.

Long Eared Owl by Guy Coheleach, 1967. Edition of 400, original price $30.

Audubon’s turkey gobbler, the most expensive print in the collection, today commands a price in excess of $20,000. All this is fine if you had a great-great grandaddy who liked prints and looked out for you, but if he didn’t, should you expect a reasonable return on your investment without waiting a hundred years? And in this day of double-digit inflation, when everyone is looking for somewhere to invest their money to protect themselves, how smart an investment are limited edition collector prints?

Long time-gallery owner and print expert Ruth Pollard, author of the “Official Price Guide Collector Prints,” says there is no way to predict the value of a print two or three years after it is issued, but she believes there are some things consumers can do to get the odds on their side. “I think the single most important thing to consider is the amount of advertising the publisher does on the artist. A lot of people believe it’s the artwork that sells the print, but that’s not true. Of course, the artist must be good, but it’s the publisher and the amount of money he is willing to spend that determines the success of a print or in fact, the success of an artist.

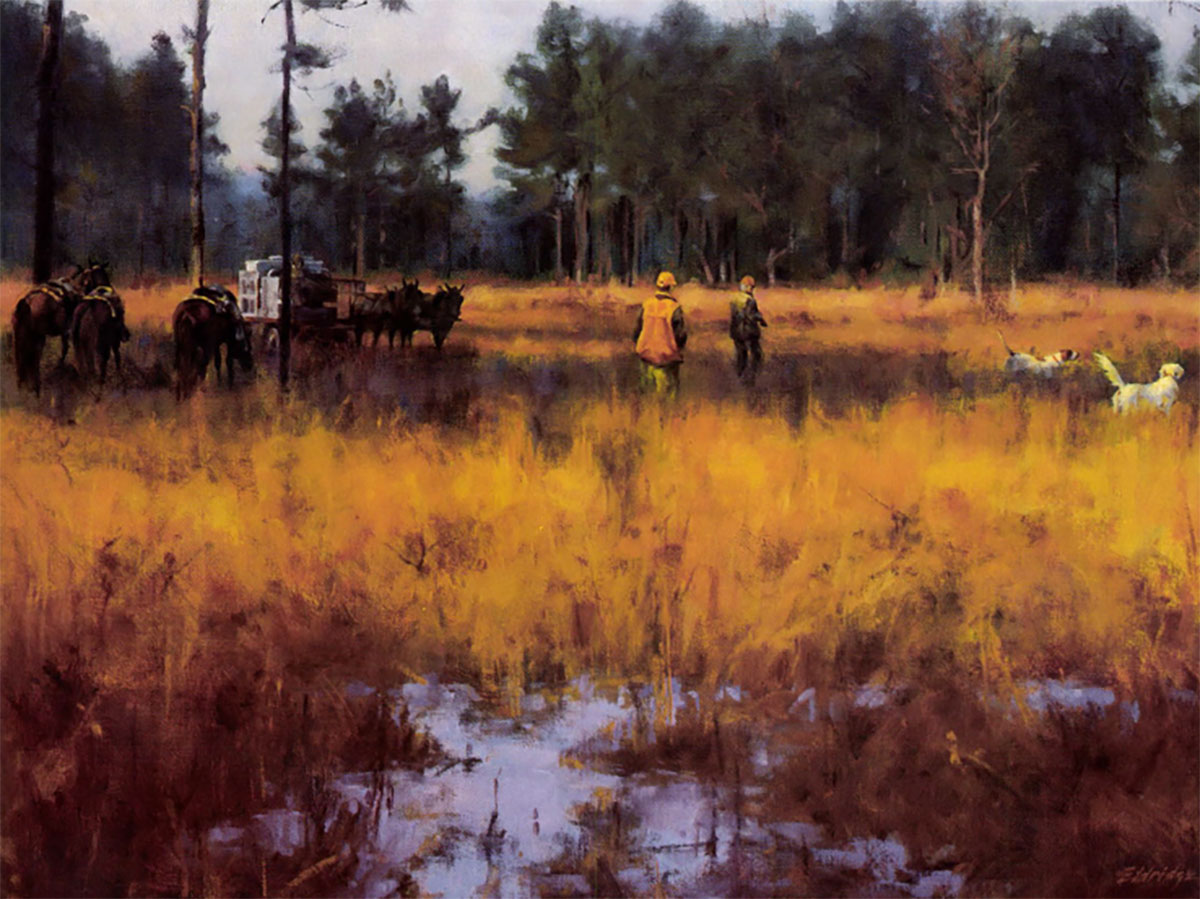

Windfall by Robert Abbett, 1974. Edition of 550, original price $55.

“The artists are not the ones who make this business,” she said. “It’s the publishers. Without the right kind of promotion, they get nowhere.”

To the person buying for investment she recommends sticking to editions of less than 1,000 and buy only from a reputable gallery. “Buy from people you can trust and they will help you move the print if you decide to sell it later or they will take it in trade for a more expensive print. You should expect the gallery to take from 25 to 30 percent on a sale.”

Are prints good investments? “You bet they are,” she says. “Not all of them appreciate in a spectacular fashion, but a good print almost always goes up, and some of them do extremely well.

“I have also advised publishers not to issue too many prints by one artist in a given year. I think the market can be overloaded with one artist, and when that happens the chances of any of the prints gaining value rapidly are slim. Personally, I don’t think any artist should issue more than five prints in a calendar year.”

Jim and Lucille Prevost, owners of the International Gallery in Vancouver, Washington specialize as print brokers. They take prints on consignment, advertise them for bids, and take a percentage of the sale. “We are definitely getting the prices now on collector prints,” Lucille Prevost said. “In fact, in many cases we are getting more than the so-called established prices.”

She said their business has picked up 500 percent over last year, both on new and secondary markets. “I think one reason prints are doing so well now on the secondary market is because of the economy. People are also learning that prints can be good investments.”

Prevost says the seller could establish a minimum price he will take for a print, and if it’s a good price, they could move it quite fast. “It’s really no way to tell,” she said. “Sometimes they move the first day, others take a little longer. As a general rule higher-priced prints move slower, but of course that’s not always true. A complete series or large collection of a single artist will be slower to move because the price is so high. These things can run into thousands of dollars and we have to find someone who has that kind of money.

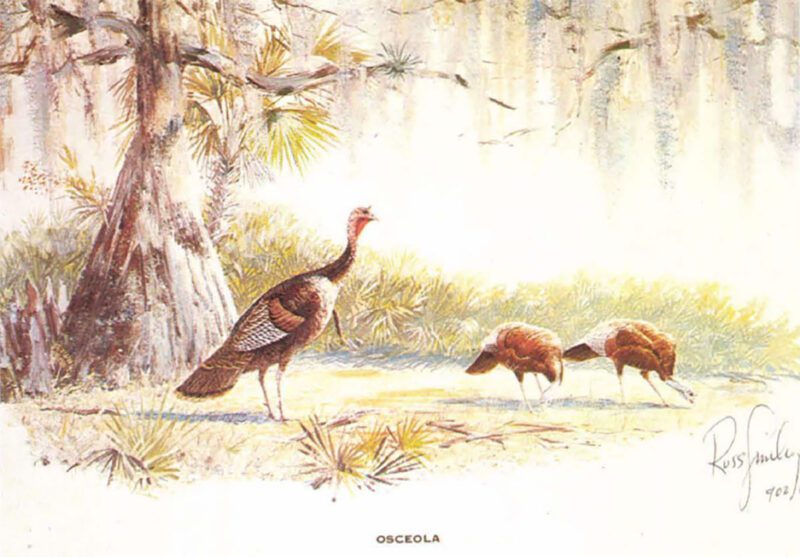

Osceola by Russell Smi!ey, 1976. Edition of 1000, original price $60.

“Prints do best when a good artist has a good publisher and they work together well.” Talk to any reputable publisher about secondary market values. He or she will quickly go into a defensive position and start issuing disclaimers. It’s almost an international creed among publishers: “We always tell people to buy what they like, and if it appreciates in value that is just an added benefit.”

In fact, one publisher says he tries to discourage all their dealers from telling buyers that their prints will go up in value.

It makes good business sense. All prints don’t appreciate in value: in fact, some of them are virtually worthless on the secondary market if not sold as a complete edition. A publisher can have an educated “feeling” about a print and its prospective demand among the buying public, but that’s all, a feeling. Certainly no publisher would ever issue prints of a subject that he didn’t think would sell, but he never knows.

So much in this business is riding on reputation, from the standpoint of artists, publishers, and galleries, that they can’t afford to issue predictions that may not come true.

But where does the real truth lie? A good many artists are just like money in the bank. John P. Cowan, for instance, has issued some 28 prints through Meredith Long Galleries in Houston that are listed in Pollard’s “Official Guide.” Out of the 28, every single one an edition of 600, and all selling initially in the $40 to $75 range, there are 12 currently valued over $600, seven more that have doubled in price, and every single one has gone up enough to classify it as a “good” investment by any standard.

Misty Morning Mallards by David Maas, 1975. Edition of 580, original price $85.

David Maas’ Misty Morning series, six prints issued from1972 through 1976, sold originally for $50 to $85, now bring $900, $700, $700, $650, $600, and $400 on the secondary market! And the list goes on and on.

It would seem then that we should invest our money in the established artists working with a strong, creative publisher. I can’t disagree, but some of the more spectacular investments have been the early prints of virtually unknown artists. Had we been lucky enough to come across little-known Guy Coheleach’s Long Eared Owl in 1967, we could have bought a copy for $30 and today sell it for $1,000 — if we were so inclined, which we probably wouldn’t be. Coheleach’s talent was apparent then, just as there are new artists today whose work will likewise grow in value.

Then there are unique situations we should watch for. The National Wild Turkey Federation started its print and stamp program in the late seventies to raise funds for the organization. Its first print, Oceola, was done by Russ Smiley, and sold for $60. Today, just five years later, it’s bringing $2,300 on the secondary market.

Prints aren’t always easy money, however. For every one that show a spectacular increase, there are 10, or 15 that do not. What we can do is show judgment in art, buy only quality reproduction from publishers with good reputations, and deal with a gallery we trust.

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared in the 1981 September/October issue of Sporting Classics.

Aesthetically, you’ll find a design with plenty to like: a hi-visibility “Antarctic Survey Orange” front cover and “Polar Night Black” back cover, with a subtle varnish effect featuring a topographic map of Antarctica. The body pages feature our popular dot-graph paper printed in light gray. Note: Synthetic paper is nonporous and does not absorb ink like our conventional papers. Ballpoint pens, pencils, or fine tip Sharpies work best. Buy Now

Aesthetically, you’ll find a design with plenty to like: a hi-visibility “Antarctic Survey Orange” front cover and “Polar Night Black” back cover, with a subtle varnish effect featuring a topographic map of Antarctica. The body pages feature our popular dot-graph paper printed in light gray. Note: Synthetic paper is nonporous and does not absorb ink like our conventional papers. Ballpoint pens, pencils, or fine tip Sharpies work best. Buy Now