Traditional archery has a way of embedding itself irrevocably into one’s psyche, and there are a few folks for whom it goes well beyond shooting or hunting.

Grandpa loved to feed his hogs. He would trudge across the narrow tar-and-gravel coal road there in the bottom of the hollow in his high-top work shoes and old denim overalls at the end of each day, and then pick his way up the dusky wooded trail to his hog pen, the bucket of food he carried for them as full as he could manage.

He would slowly and meticulously roll a smoke from his pocket tin of tobacco as he watched them feed, and then linger there in great satisfaction— for one blissful hour alone and in control of something he could understand, free from the fragmented elements of his life that daily burdened him and that he often found difficult to manage.

It would usually be well past sunset before he’d head back down the darkened trail toward home and an always-too-abbreviated sleep, dutifully rising again in the dead of night for another day’s effort to keep his family and his hogs fed.

Each of us has one or two such small and seemingly insignificant things in our lives that provide a similarly inordinate measure of gratification and pleasure.

It might be something as simple as a tattered but comfortable old flannel shirt, one that has kept you warm from the great salmon rivers of Alaska to the high elk, deer and sheep country of the American Southwest to the rivers and plains of Patagonia, gaining ever more wear and endearment with each new adventure.

For some, it may be tying beautiful but dangerous trout and salmon flies or building fine bamboo fly rods. For others, it might be an invigorating game of chess or tennis or cribbage.

For Grandpa Altizer, it was the simple pleasure of feeding his hogs.

But for me, it’s the making of my own wooden arrows, and then shooting them from one of my old recurve bows.

This is something I enjoy profoundly, and over the years I have derived countless hours of deeply personal, even selfish, satisfaction—so much so, in fact, that many, if not most of you, will perhaps find fault in what I am about to write and may even take offense, though I assure you, no offense is intended.

In places, it will be admittedly adamant and exclusionary, even elitist, its perspective narrow, its presentation terribly biased and dogmatic to the point that I feel I should apologize right up front for my personal prejudice. The problem is, I just can’t bring myself to do it.

So, having provided proper forewarning, those who shoot a compound bow might now find it best to turn the page and move along to the next story.

Full disclosure: I still own two compound bows and parts of yet another, stashed away for years in our back storage room, and I can think of at least three more that I have given to friends over the years. There may even be a few old videos still floating around out there that show a darker-haired and much younger version of myself hunting deer and elk with such with a compound.

But my ill-considered infatuation with high-tech compound bows lasted only for a year or so, and I gave up on them decades ago. For you see, my heart always has and always will belong to the more traditional recurve bows of my youth.

Now, lest you misunderstand, let me state right up front that I have absolutely no issues whatsoever with anyone who chooses to shoot a compound bow. You are, after all, essentially doing the same as I am: flying arrows to whatever target you may choose, be it paper, straw or leaf…feather, foam or fur.

All of us who do such a thing share a certain bond of understanding, and our only differences lie in the equipment we choose. But I would no more deny you your choice of weapon than I would change my own.

My brother recently told me about meeting a fellow in Ohio who had been introduced to archery back in his late teens and began by shooting compound bows.

“It was wonderfully enlightening,” the man told him. “I had never experienced such a thing. It was like stumbling into some glorious garden I never knew existed, filled with beautiful blooms.”

Then the man continued. “But it wasn’t until I began shooting a traditional recurve bow last year that I actually began to smell the roses.”

Traditional archery has a way of embedding itself irrevocably into one’s psyche, and there are a few folks for whom it goes well beyond shooting or hunting. Some of us make our own arrows, and a few (my brother included) even make their own bows.

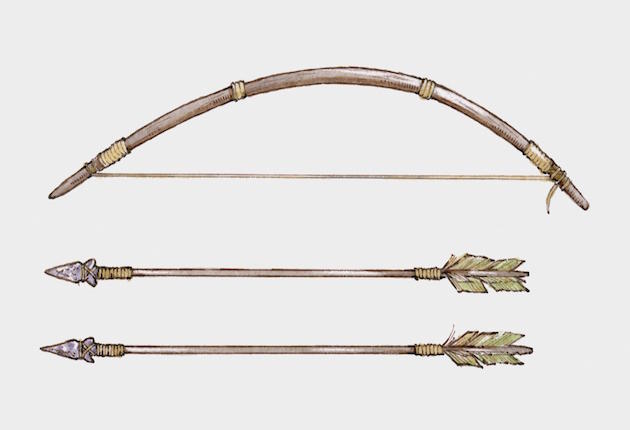

I take great pleasure in making my own arrows. Some folks make arrows in multiples, but I make them one at a time. I think of arrows as individuals, if not works of art, each deserving of my full and undivided respect and attention. For each possesses its own subtle traits and flight characteristics, even though I take great care to make them all with as much consistency of materials, weight, length and spine as possible.

Sometimes as a particular arrow takes form, I sense from its very inception that it is going to turn into something even more special than normal. It may be the fine-grained character or the sweet, cleansing aroma of the classic Port Orford cedar I have chosen for its shaft, or the latent energy I feel as I pull it raw and unfinished through my fingers and across my palm or the cut and curve of the individual barred turkey wing feathers I select for its fletching.

It speaks to me throughout the long and detailed process of straightening and finishing its wooden shaft and applying my own signature cresting and final varnish, then sculpting and tapering its ends for nock and point.

I angle each feather along its base one at a time and secure it in place with glue or sinew, finding expression and promise in the covenant between it and myself as to what we are destined to experience together once the arrow is finished and I loose it on target or game.

As it comes to life in my hands, I feel a bond with all the other arrow makers who have gone before me, whether Cherokee or Apache, Seminole or Sioux, Cree or Cro-Magnon. I imagine what they must have felt, know what they must have known, and hope what they must have hoped as their own arrows took form. And if somewhere early in the process my materials fail to speak to me in such a voice, they are likely discarded, and a new arrow begun.

There are few things more honest than a good handmade arrow. It flies true and unrepentant, its trajectory defined by the same laws of physics that govern the entire universe, its power and energy derived from the archer’s own life force. When it flies, Time becomes a meaningless element, and for that one blissful moment my arrow exists only in present tense, fulfilling its purpose, moving swiftly through the air, its angled fletching imparting spin and stability, its steel point eager for its mark.

But such an arrow has an even greater and more sublime purpose—as the perfect place to record a lyric or line or literary verse, handwritten along its smooth, wooden side in indelible ink. For, apart from deep in your soul, a handmade arrow is the most ideal repository for such treasures—a sentence from Robert Frost or Seamus Heany, a lyric from David Crosby or José Martí, a verse from the Book of Ecclesiastes or the Song of Songs—to be drawn from your quiver and read in moments of abject need or divine inspiration.

But alas, there is a time for contemplation and there is a time for action, when all the thought and effort and preparation you have invested in your arrows must finally yield to the consummate pleasure of actually shooting them, whether at some inanimate target or at a living animal, or perhaps even some winged creature thundering into the crisp autumn air.

And when your bow is drawn and the shot is taken, you want to take another— and another, and another and another still. For the blessing resides not so much in the shot but in the shooting, and in all that has led up to the moment at hand.

So, here and now, I must again confess…building and shooting my own handmade arrows from one of my traditional recurve bows is a very selfish thing for me to do, a purely personal indulgence, one which so many others in this worrisome world who are far less fortunate than I am have neither the time nor the inclination to pursue.

They are far too preoccupied with the basics of living, such as keeping safe, staying warm, providing shelter and putting food on the table.

Or perhaps even feeding their hogs.

This is a full-color edition of the very first Boy Scouts Handbook, complete with the wonderful vintage advertisements that accompanied the original 1911 edition, Over 40 million copies in print!

This is a full-color edition of the very first Boy Scouts Handbook, complete with the wonderful vintage advertisements that accompanied the original 1911 edition, Over 40 million copies in print!

The original Boy Scouts Handbook standardized American scouting and emphasized the virtues and qualifications for scouting, delineating what the American Boy Scouts declared was needed to be a “well-developed, well-informed boy.” The book includes information on The organization of scouting, Signs and signaling, Camping, Scouting games, Description of scouting honors and more. Scouts past and present will be fascinated to see how scouting has changed, as well as what has stayed the same over the years. Buy Now