Is this the world’s greatest freshwater gamefish?

Hop a Cessna Caravan and leave the city of Santa Cruz, Bolivia and its 2.5 million inhabitants and it isn’t long before you’re swallowed by millions of acres of untrammeled jungle. The forested hills and valleys surround a labyrinth of river systems full of exotic fish species ranging from 200-pound moturo catfish to saucer-sized paku that don’t so much bite a fly as they mug it. For fly fishermen in search of the greatest fighting freshwater species, however, many believe the region’s golden dorado has no rival.

The fish terrorizes the aquatic food chain the way lions haunt buffalo herds. Watching a handful of golden dorado hunt as a pack, cornering schools of sucker-like sabalo, before ripping into them with the speed and savagery of so many barracuda, is one of the world’s great predatory spectacles.

A 75-minute charter flight from Santa Cruz and visiting anglers are greeted by indigenous people who are part of Tsimane’s sustainable model. CHRIS DORSEY, DORSEY PICTURES

It’s that same viciousness they use to strike a fly, contorting and bending eight and nine-weight fly rods into question marks. What every angler who has ever hooked a golden dorado asks himself in that moment is simply: Can I land this fish?

Beyond its electric yellow color, the next feature you notice about a dorado is its outsized head and jaws. Watch a guide carefully unhook one of the fish and you’ll see how much respect they have for the dorado’s teeth — nothing but pliers are ever used to extract a fly…at least after one attempt using fingers.

Their combination of size (some golden dorado can stretch well past 30-pounds), speed, leaping acrobatics and striking mug were all the enticement I needed to see for myself if they were, in fact, the planet’s greatest freshwater gamefish species. Africa’s tigerfish, the Amazon’s peacock bass and the pike and musky of the north country rightfully contend for that crown as well.

Colorado anglers Will and Brad Coors have plenty of reason to smile after landing one of the hefty golden dorado for which Bolivia’s Pluma Lodge has become famous COURTESY OF BRAD COORS

Of all the places to find golden dorado, few rival the wilds of Bolivia for its abundance of the fish as well as their outsized dimensions. For Marcelo Perez, a 50-something Argentinean architect turned fishing lodge developer, the pristine waters of the 2.4-million-acre Isiboro Secure National Park was the ideal place to construct a series of destinations for his Tsimane Lodges, a series of premium destinations catering to anglers from across the globe — most of whom arrive from America.

I joined a group of anglers from Colorado and South Carolina as we began six days of fishing at Tsimane’s Pluma Lodge. The sprawling lodge consists of a series of well-appointed private rooms with hot showers and comfortable beds. The river winds below the lodge and consists of a series of shallow flats, riffles and the occasional deep pool. As the sabalo migrate up the river beginning in late May, the dorado follow them, never straying too far from their favorite food source. By October, the baitfish begin moving back downstream and, with that, the dorado season ends.

Tsimane’s Pluma Lodge is a sprawling and well appointed destination for anglers in the heart of Bolivia’s best golden dorado fishing. CHRIS DORSEY, DORSEY PICTURES

The first morning I head far upriver with Agustin Tettenborn, a 23-year-old Argentinean guide who is in his second season at the lodge. Our beat is a gin-clear creek framed by giant boulders, steep hills and the occasional waterfall. After a few casts, it becomes clear that this is not a destination for a beginning fly angler, for the need to make 60-to-80-foot casts isn’t uncommon. If you want to catch fish, that is. The demands of hiking several stretches of the river for long distances, moreover, requires a level of fitness on par with a day of fishing on a mountain trout stream. If you’re thinking of making the trip to Pluma, commit to getting in shape and you’ll not only improve your chances of landing more fish, but you’ll also have a far more enjoyable adventure.

While we were able to spot a few fish before casting, for the most part we spent much of the day blind casting in riffles and pockets of water where Tettenborn knew fish liked to hold. Later in the afternoon, however, we emerged into a pool half shaded by house-high boulders and a couple of tentacled almendrillo trees. As we waded into the knee-deep water, Tettenborn spotted a dorado holding on the edge of the shadowed water.

“Cast at 1 o’clock…quickly.”

Wooden boats built by indigenous people who partake in Tsimane’s guiding efforts are used to transport anglers throughout the region. CHRIS DORSEY, DORSEY PICTURES

Two false casts and I delivered the eight-inch red and yellow fly in front of the fish’s nose, stripped twice and the dorado grabbed the streamer and went airborne in the same instant. The 20-pounder transformed the pool into a blender with its airborne displays, protesting my hookset violently as it contorted skyward time after time. The first instant you play tug-of-war with one of these beasts — especially a double-digit brute — you understand why anglers travel halfway round the world to catch them.

For the typical angler who can double-haul (that is, shoot line forward and backward during the casting process), Tettenborn says you can expect to catch 15 to 25 fish in six days of angling, which was confirmed by what our group experienced. After blind casting for several days, you’re apt to feel like a baseball pitcher used a few too many times in the rotation. Ben Gay and bug spray, in the middle of the jungle, run about the same price as gold.

It is something of a miracle how a fly fisherman’s shoulder seems to recover quickly, however, at the sight of big fish. Such was the case as Tettenborn eased up to a natural rock dam on the edge of the river, with the spillover heading to a small separate channel.

“Do you see those two dorado sitting there?”

Some 50-feet ahead of us were two 20-pound (or more) dorado, parked like two submarines at port. I will have one shot to put the fly where it needs to be, or the fish will spook and the opportunity will be blown. Two false casts and I drop the fly two feet upstream from them and strip it as the current brings it past their noses.

South Carolina resident Steve Hicks hoists one of the river monsters that lurk in the waters near Bolivia’s Pluma Lodge. JOHN MACGILLIVRAY, DORSEY PICTURES

Both fish lunge at the fly with the winner leaping into the sky, the dorado being the bull and me the rider praying to hang on. Four jumps into the fight and the fish spits the hook, but when the fly hits the water, a smaller dorado pounces on it. As I begin to bring in the lesser of the two, one of the 20-pounders attacks the small fish, biting it in half. I lift the tailless dorado out of the water as the two behemoth dorado beach themselves at my feet in an effort to consume the rest of the fish. It’s as if they are killer whales desperate for a meal of seal. The dorado are oblivious to anything other than their predatory frenzy, paying no attention to me whatsoever.

In that moment, I couldn’t help but ponder again: Is this the world’s greatest freshwater gamefish? I doubt anyone who has hooked one would say otherwise.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in Forbes.

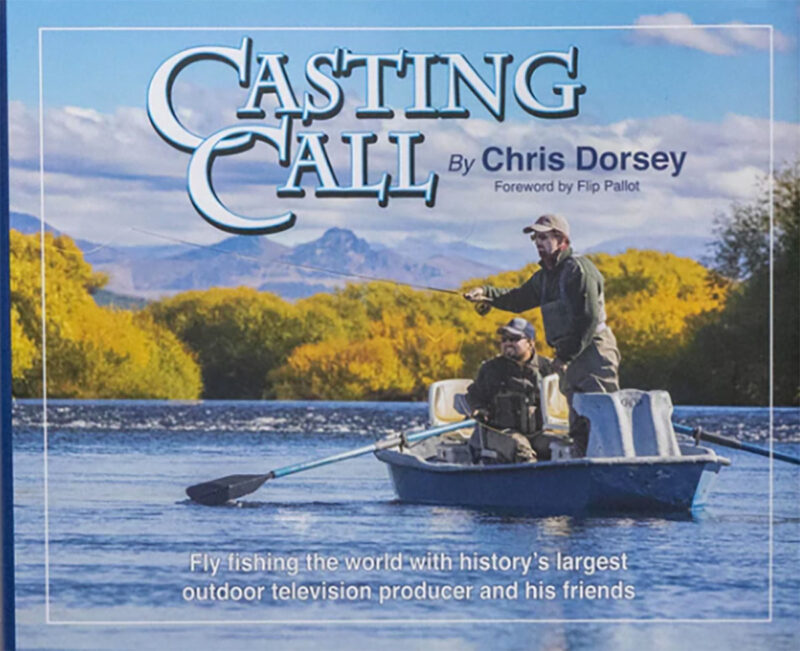

From one of the world’s most widely traveled fly fishermen and the largest producer of outdoor television in history comes the first of its kind celebration of the planet’s greatest fly angling. Chris Dorsey’s new book and film set, Casting Call, takes readers and viewers to epic fly waters from the American west to Alaska, across Canada, to the fabled flats of the Bahamas and Belize to the jungles, marshes and highlands of South America and many points in between.

From one of the world’s most widely traveled fly fishermen and the largest producer of outdoor television in history comes the first of its kind celebration of the planet’s greatest fly angling. Chris Dorsey’s new book and film set, Casting Call, takes readers and viewers to epic fly waters from the American west to Alaska, across Canada, to the fabled flats of the Bahamas and Belize to the jungles, marshes and highlands of South America and many points in between.

Internationally acclaimed photographers Dusan Smetana, R. Valentine Atkinson Marcos Furer, John MacGillivray, Francois Botha and others spent thousands of hours in remote locations to capture a stunning collection of images that help make the 300-page opus an instant classic. Each chapter also features a 10-minute corresponding film shot on location during the creation of Casting Call. Buy Now