A South Carolina man transforms ancient cypress, some over 55,100 years old and stood during the Glacial Period, into top-tier turkey calls.

Researchers at the University of Georgia dated the cypress log at 55,100 years old, but admitted it may, in fact, be much, much older. They explained to John Tanner, a game-call maker from Hemingway, South Carolina, who provided the sample, that the carbon-14 dating process can’t accurately determine the age of material older than 55,100 years, so the number serves as a cap. Even so, the log’s youngest-possible age still places its lifetime within the last glacial period – an epoch when vast ice sheets entombed much of the Northern Hemisphere, when mammoths and mastodons still roamed North America’s endless snowy plains and few humans had yet to creep from Africa and scatter across the world’s greater expanses. And now Tanner has managed to salvage timber from this era, fashioning it into turkey calls and, in a way, returning it to the very swamp and forest from which it came.

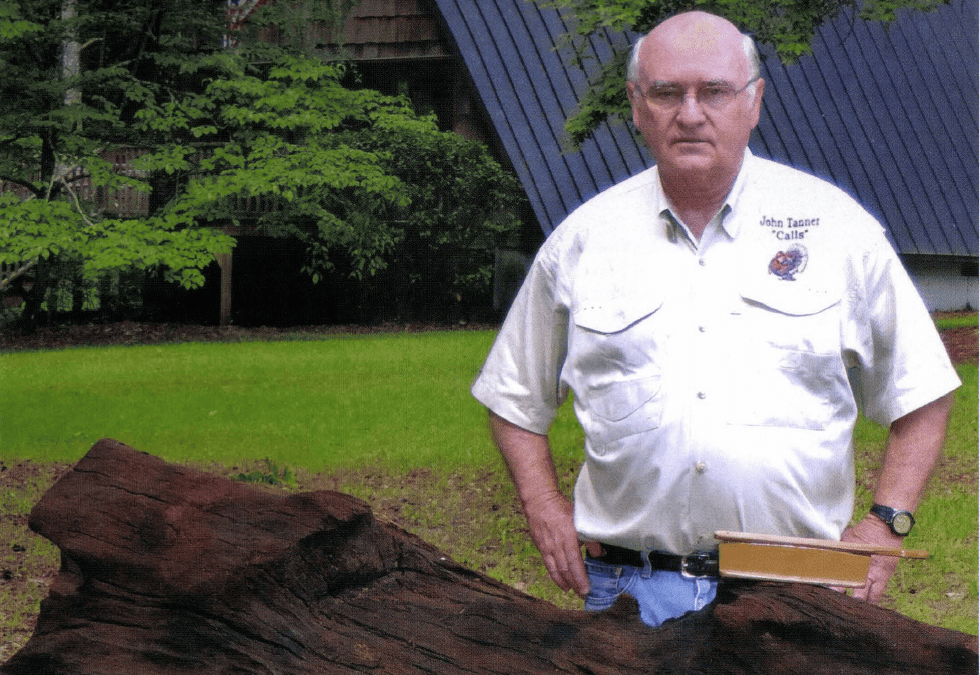

Tanner is a longtime resident of South Carolina, leaving the state only for brief stints as a young man. He lives on the same tract of land where he grew up, and his woodshop and hunting clubhouse sit on a plot of family-owned property nearby. He’s the kind of guy who likes where he’s from and wants you to know it. And his devotion to this little postage stamp of land is largely responsible for why he began hunting turkeys and coaxing gobbles from chunks of wood that predate Christ.

How It All Began

It started with sand mining, of all things. Sand mining in river beds – such as those along Lynches River, which rolls through the center of Williamsburg County not far from Tanner’s home – requires workers to burrow 35-foot holes into the earth to reach the granular rock. Often, as workers dig, they must exhume from these holes long-buried logs and debris, which they often burn afterward. But as Tanner tells it, one day nearly ten years prior, a cousin of his was at a mining site and began to wonder whether this wood had any value. After having a sample carbon dated and discovering its age (this first sample was approximately 47,000 years old), he called Tanner to figure out what to do next.

Through Tanner’s involvement in the community, he had assumed a chair on South Carolina’s Wildlife & Fisheries Advisory Board, which helped counsel the state’s Department of Natural Resources. Tanner, who spent his career in information technology, first turkey hunted during an outing with members of the board in the late 1980s and quickly became an enthusiast of the sport. Given his experience afield and knowledge of environmental and wildlife issues, it’s not hard to imagine why Tanner’s cousin would seek his insight.

Tanner carved this box call from ancient cypress pulled from the Lynches River in South Carolina.

The two men began meeting monthly, as they knew they could use the wood but struggled to agree how. After several fruitless discussions, Tanner declared he wanted to build box calls from a chunk of the log, though he had no idea how, regardless of what his cousin decided to do with the rest. When Tanner told me this story, he spoke as if making calls seemed like the only obvious thing to do with the remains of an ancient, prehistoric tree, despite never having made a call in his life. I couldn’t help but like him for it.

Turning Ancient Wood into True-Sounding Turkey Calls

After Tanner’s proclamation, he spent the next three years developing a method to turn the wood into true-sounding, sturdy calls. To do this, he had to first learn to properly dry and shape the wood. He admits his first models – rough-looking and glued together from individual pieces of wood – left room for improvement but thorough testing and nearly 50 prototypes eventually gave way to a solid-bodied design he could stand behind, yielding his first batch of top-tier ancient cypress box calls in 2006.

But wood doesn’t last forever. After making this first collection, Tanner’s cypress supply began to dwindle. He then decided to have a second log dated, hoping it would be as old as the first. Much to his surprise, researchers at University of Georgia concluded this sample was even older than the first, dating back 55,100 years old, give or take a margin of error.

But the problems working with this ancient log proved even more trying than those of the first. Wood this old deteriorates over time, becoming brittle and difficult to mill and carve. Though Tanner had challenges with the first log, he could work it with relative ease. But with this second much-older log, Tanner had to throw away half the turkey calls he’d built, unable to draw a realistic sound from the wood. And other times the calls simply fell apart.

Undeterred, Tanner kept experimenting with the wood but struggled to come up with a practical solution.

Perfecting the Final Product

Finally, after much testing and brainstorming, he realized he could use a vacuum to remove oxygen from the wood and fill the resulting crevices with a stabilizing agent to strengthen the sample. The result provided him with a material he could shape into durable, natural-sounding calls. From what Tanner can determine, he’s the first and only person to ever successfully make box calls from wood this old, let alone models that sound this good.

These days Tanner laughs about the experience, but he surely felt anxious once his handcrafted calls began crumbling in his hands. His ability to transform ancient cypress into functional, beautiful calls stands as further testament to his skilled craftsmanship. At what point, I asked, does he know he’s found a call’s perfect timbre. He said it was simple: He just takes the call from his shop, strikes out into the cypress stands, and lets the turkeys be the judge.

The Literature of Turkey Hunting is a critical reference source, including prices, for anyone interested in books, pamphlets, brochures and published ephemera on turkey hunting. Buy Now

The Literature of Turkey Hunting is a critical reference source, including prices, for anyone interested in books, pamphlets, brochures and published ephemera on turkey hunting. Buy Now