Several years ago at a small gun show in a church social hall, I bought a Parker DHE with a second set of barrels with a non-matching number for $700. I tried hard to convince the owner that he could get twice or three times as much from someone else, but he insisted I take it at that price.

To be sure, the Parker was well used. Its stock carried a multitude of shallow dings and scratches and the checkering was worn smooth. To protect his fingers from recoil, a previous owner had silver soldered a flange behind the trigger bow. Grey patina had overtaken the action’s original case coloring, and the barrel’s bluing was mottled, though the bores were shiny and unpitted. The action closed snugly, and the barrels didn’t wobble discernably when shaken. The second set of barrels didn’t lock up firmly. Even so, this Parker was one hell of a bargain.

Figuring there might be something seriously amiss inside that I could not see, I took it to my gunsmith, Michael Merker of Hendersonville, North Carolina. Michael restores vintage doubles by Holland & Holland, Rigby, Boss, and others. He checked out my Parker, removed the flange from the trigger and, with a bit of judicious filing, fit the second set of barrels.

Next stop was the five-stand range at Biltmore’s Sporting Clays Club where the old gun functioned well. Smartly, the ejectors kicked out fired shells. Every once in a while when I closed the action, the top lever failed to snap all the way over and line up perfectly with the tang. It wasn’t a big problem. Every time I took it out to shoot, folks admired it and often suggested that I have it restored.

In my rack was an L.C. Smith 16 gauge with 26-inch barrels choked improved cylinder and modified. It’s my go-to quail gun and the only one I own that had been restored. When I acquired it from Michael, he said he thought the work had been done by Turnbull Restoration. I queried them, however, they had no record of it. Perhaps the firm had reworked the gun before it began keeping records of each restoration project.

Head Craftsman Sam Chappell smokes the breech face prior to filing the barrels to return them to perfect and safe tolerances.

Having long admired the work of Turnbull Restoration, I shipped them the Parker for a free quotation. A couple of weeks later, I received the estimate to make it look and function as if it were factory new. I was floored. The stock and forearm needed to be replaced and recheckered. Engraving on the action, trigger guard, skeleton butt plate and each screw needed to be recut. All the markings needed to be refreshed. And then, there was polishing, rebluing and case coloring. All told the estimate came to $15,800.

But along with the estimate came the observation that, while they’d be pleased to do all this, it would cost more than the gun would ever be worth. Such honesty was utterly refreshing, and it made me think about Parker’s inherent value.

Having previously joined the Parker Gun Collector’s Association, I’d swapped emails with its historian Chuck Bishop to ascertain the history of a 12 gauge Trojan with two sets of barrels with matching serial numbers. I dropped him a note asking about the origin of the DHE. He told me its barreled action was manufactured toward the end of 1906, special ordered by mail on April 14, 1908, and shipped out with its straight grip stock and 30-inch, full-choked barrels a week later to J. G. Schmidt & Sons, a sporting goods store in Memphis. Its original price: $125.

When I felt its well-worn checkering and saw the dents in the stock, I wondered how many others had enjoyed it as much as I had. What had it hunted? With both barrels full-choked, had it spent time in a live pigeon ring? That its bores were nearly pristine was evidence that its prior owners took very good care of the gun. Still, it had seen a century of use. Was it mechanically sound?

What if I were to forego cosmetic refinishing and, instead, have its innards restored to factory new tolerances? I discussed that idea with Doug Turnbull and Mike Nelson, his director of marketing.

The notion resonated deeply with Doug. We talked about returning family heirloom guns to full factory functionality, while preserving the record of dad’s or granddad’s hunts as told by the faded colors and dings and scratches in the stock.

Unbeknownst to me at the time, Turnbull Restoration’s motto is “Shoot History.” Nothing pleases him more than to return a fine old piece to service.

With that in mind, I flew up to their shop in Bloomfield, the head of New York’s finger lake district. By the time I arrived, Sam Chappell, Turnbull’s lead gunsmith, had disassembled the action. While I’d seen exploded drawings of Parker actions, I was astounded at the scores of tiny pins, fragile rods and levers, and delicate springs that had to fit and function precisely inside the action. In my mind’s eye, I saw workmen, bent over their benches, filing and stoning each part so it fit just so.

“It’s pretty cool to see the way the builders took pride in their work,” Sam told me.

“The inside is just as good as the outside.”

Holding up the disassembled action frame, he wondered, “How did they machine this?” Pointing to a slot beneath the watertable, he said, “They were gracious enough to put a hole here so you can trap the cocking rod hammers to take the pressure off the hammer screws.”

Even some of the smallest parts were numbered or lettered so, for instance, one could easily distinguish the right ejector components from the left.

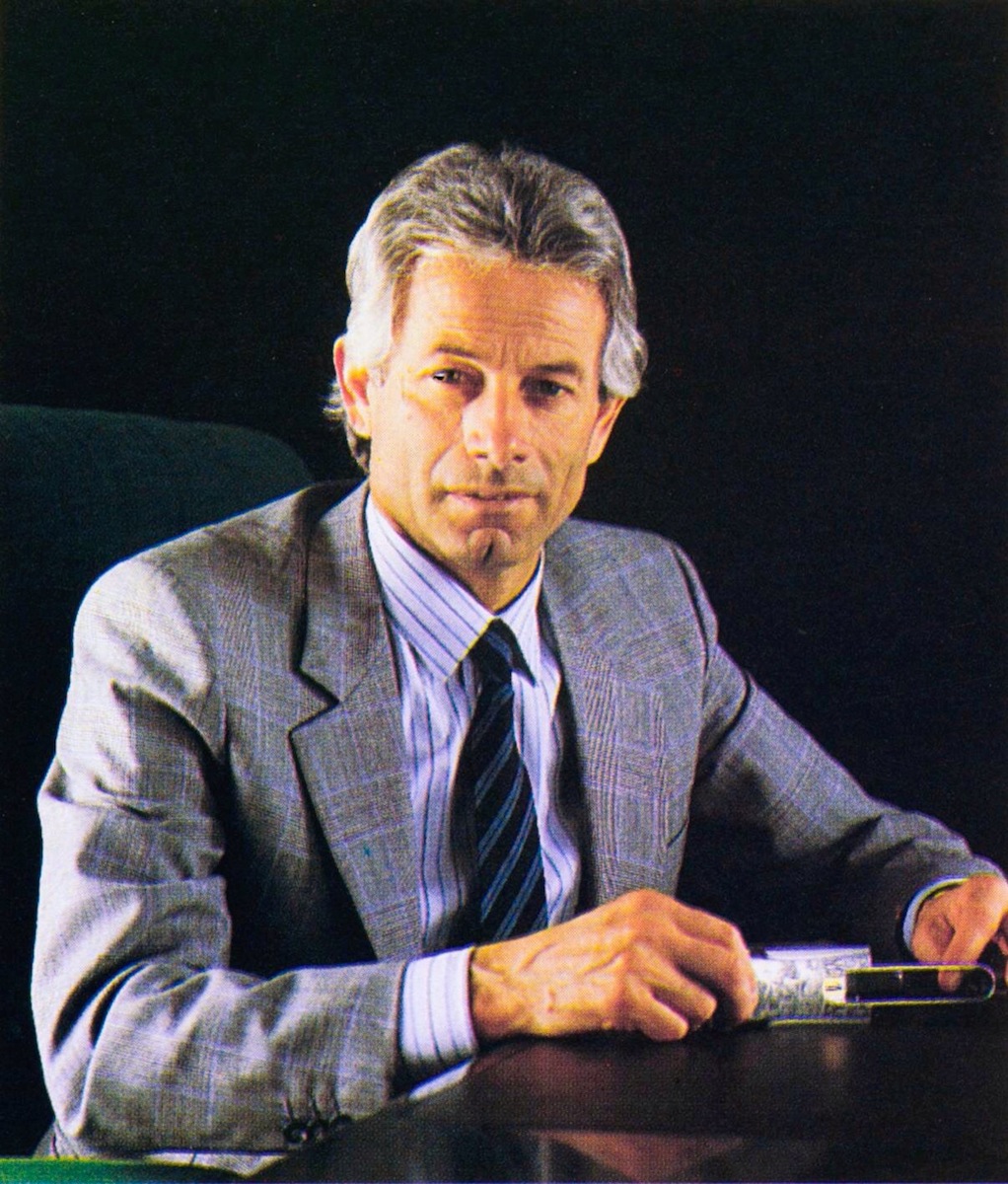

Doug Turnbull holds a high-grade Parker that he and his craftsmen restored to its original condition.

Parker Gun Identification and Serialization, the definitive source on Parker Bros. shotguns, contains excellent photographs of engraving on DHEs and all other grades, including details that vary from gun to gun. Mine, for instance shows a pointer on the left side of the action and a setter on the right. On the one in the book, the placement of the bird dogs is reversed.

According to Sam, Parker engravers only had to follow a general pattern and were free to articulate it as they saw fit. Thus, each high-grade Parker is a custom gun.

I’d thought mine was pretty tight and safe to shoot. He found otherwise.

“There should only be a gap of about .001 inch between the breech face and the barrel,” Sam told me. Brandishing a feeler gauge, he measured .004 inch. With a bit of weld, he built up the hinge and then, by smoking the ends of the barrels, he carefully filed and stoned them so they fit perfectly.

Turnbull also fit a new top lever spring, repaired the forend latch, rebuilt the damaged doll’s head barrel extension and installed the missing mid-barrel ivory bead. It’s a little stiff when I open it, just like a new gun.

Shooting history is precisely what I intended when I drove down to Moree’s Sportsman’s Preserve near Society Hill in South Carolina. It’s 2,400 acres is a mecca for scattergunners intent on bagging quail, pheasants, ducks, doves, and turkeys. I handed the DHE over to Manager Mike Johnson who grew up shooting a Fox and was delighted to give the Parker its test hunt. We followed his German shorthair as she worked through waist-high broomgrass. When the cock flushed, Mike swung, fired and was rewarded with tailfeathers.

Lamenting that he’d forgotten the barrels were choked full and full, he promised to do better when the shorthair found another bird. She did in short order; Mike fired, and down it came. As he handed the Parker back to me, he was all smiles.

Over the next few months, you’ll find me on Biltmore’s sporting clays and five-stand courses learning how to shoot the DHE. Next fall, whenever I hear cockbirds cackle, you can bet that’s the gun I’ll be carrying.