Lord Delamere symbolized the early days of British East Africa.

In 1897, the young Hugh Cholmondely, Lord Delamere, left the Horn of Africa on a lengthy shooting trip into the interior. He crossed Somaliland on foot, arriving finally on the banks of the Tana River in what is now Kenya.

The artist at his studio in England.

The Tana flows out of the highlands down to the Indian Ocean, a green ribbon swarming with crocodiles and hippos, snaking through a fly-blown land of sand, thornbush and elephant. As he stood gazing upon a river few white men had seen before, the civilization-hating Delamere thought he had found paradise. And then he saw an approaching dugout canoe, topped, incredibly, with a pink umbrella, and under the pink umbrella, a missionary.

Delamere took one look, and pushed on.

Ultimately, he reached the Highlands of Kenya, and that was paradise; in 1902 he returned to settle permanently, was granted a 99-year lease on 100,000acres of prime farmland, and embarked upon one of the most colorful careers in British colonial history — a career that included pig-sticking expeditions with Winston Churchill, and entertaining Theodore Roosevelt on the first leg of his epic safari across Africa.

With his red hair hanging in locks like George Armstrong Custer, Lord Delamere symbolized the early days of British East Africa. He also had a penchant for playing rugby in the Long Bar at the Norfolk Hotel, and for periodically shooting out the new gas lamps on Nairobi’s main street, later called Delamere Avenue, and later still Kenyatta Avenue. Lord Delamere died in 1931, his commitment to Kenya unwavering to the end.

In 1945, a second wave of settlers arrived in search of a better life than post-war ration-coupon England was likely to offer. Among them was the Combes family of Dorsetshire. The elder Combes found work on the Delamere ranch in the Rift Valley, and settled in. His son Simon, aged five, had arrived in Africa.

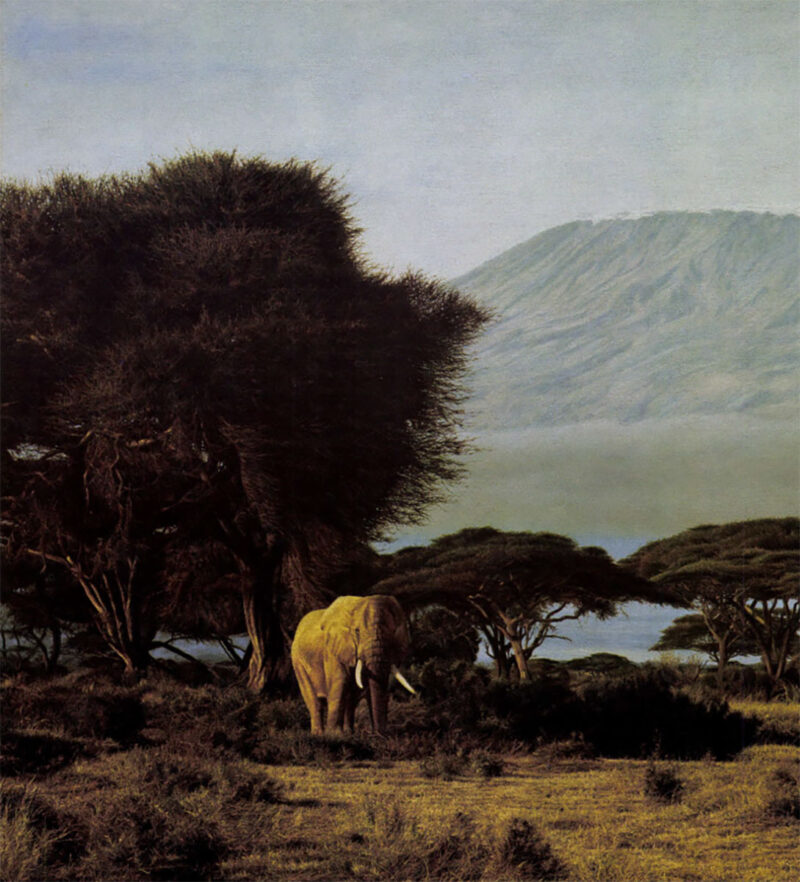

Kilimanjaro Morning.

No child ever enjoyed a more fantastic playground: 50,000 acres of Kenyan grassland, populated with very bird and animal imaginable, all watched over from a hilltop where Lord Delamere now lies buried, peaceful for once, presumably.

Today, almost 45 years later, Simon Combes talks about his boyhood on the Delamere Ranch with undiminished enthusiasm, of winning a 22 rifle in a shooting match when he was 12, and embarking on a Career as hunter in game fields the like of which no longer exist — in Kenya or anywhere else.

“I had the run of the ranch, and I made the most of it,” Combes recalls. “That was where my love and knowledge of wildlife really began.”

School, naturally, intruded, and by his teens, Simon Combes was attending secondary school in Nairobi; even school had its moments, however — moments such as the odd attack by the Mau Mau.

“Mau Mau? I remember we spent quite a bit of time building sandbag emplacements around the school. It was on the edge of one of the native reserves, and we came under attack a couple of times. Nothing really serious; a few shots, and they took off.”

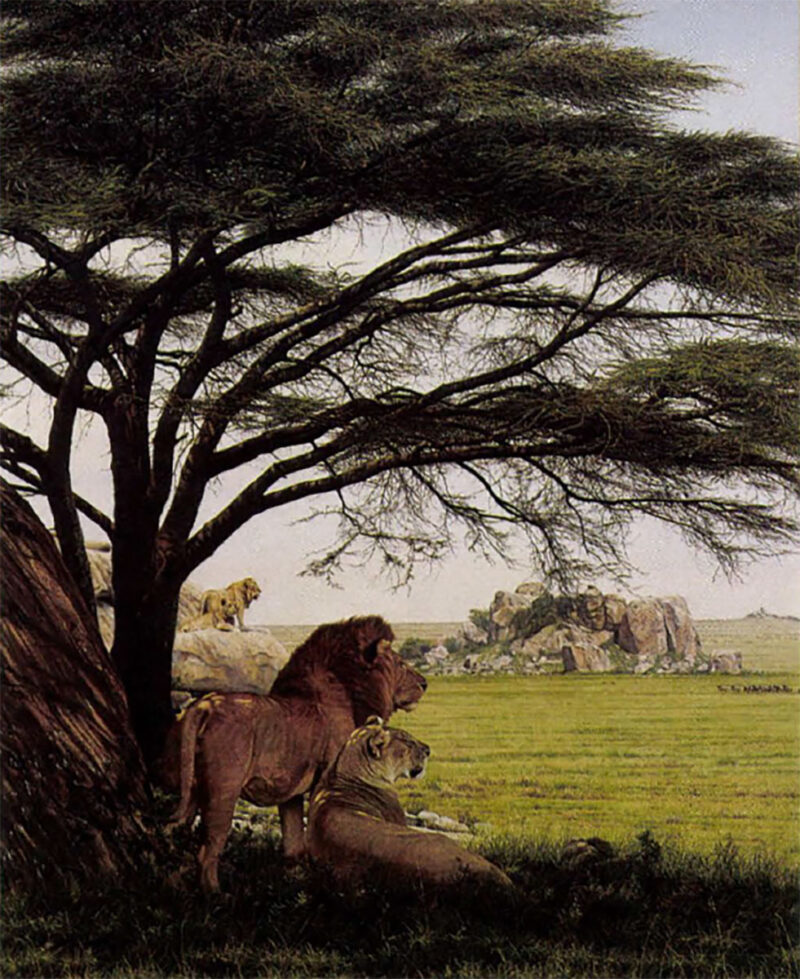

Simba – African Lion

While Simon went to school in Nairobi, his father patrolled the ranch with a six-gun strapped to his leg. His mother carried a Beretta in her handbag. The house was wired for security, and armed guards were posted nightly. Even so, in spite of the publicity given the slaughter of some white people, mostly in forested highlands, the Combes family escaped largely unscathed except for the “pretty awful” things that happened to some of Lord Delamere’s cattle, and, Simon Combes says, “when you live in Africa, you have to expect that.

“We weren’t bothered on the farm because it was open plains country. There was more Mau Mau activity in the forests over towards Mount Kenya. We did get raided a few times, of course. They’d kill cattle, take a haunch off one for food, and then hamstring 40 or 50 others and we’d have to shoot them. It was pretty terrible.”

In 1960 Combes joined the British Army and went to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. After three years he was posted back to Kenya as a junior officer in the King’s African Rifles (KAR).

When Kenya attained its independence in 1963,many of the white settlers abandoned their holdings and pulled out. They headed either back to England or south to Rhodesia as the new black Kenyan government proceeded to pull down the statue of Lord Delamere opposite the New Stanley Hotel and replace it with one of Jomo Kenyatta. Not Simon Combes. An officer in the King’s African Rifles he was; an officer in the new Kenyan Army he elected to become.

“I suppose I might have felt differently if I had been touched personally by the Mau Mau – I mean, if I had lost someone close to me,” Combes said. “The thing is, I didn’t. “After independence, when I was in the army, I met Jomo Kenyatta. His attitude seemed to be, ‘what’s past is past.’ That was fine with me.”

Tall Shadows – Giraffes

The KAR, like much of the old British colonial army, consisted of native troops and non-commissioned officers commanded by whites. The highest a black could hope to rise was a kind of honorary commissioned rank called effendi. As independence loomed for Kenya, Uganda, and Tanganyika, the effendis were tagged to become the commanders of the newly formed national armies; as the chosen, they were singled out for special training and education in deportment and command.

One such was an effendi in the KAR battalion from Uganda, a giant young fellow renowned for his strength and skill as a boxer. He was, however, a tad rough-hewn for senior rank, and so Lt. Simon Combes was despatched to turn him into a gentleman. The effendi’s name was Idi Amin.

“People seem to forget now that Idi Amin was a really popular guy in the regiment; he was a good boxer, which commands respect, and he was quite charismatic,” Combes recalls.

“He also had the gift of command. One time we had an earth tremor, almost an earthquake, during the night. The cupboards rattled and the floor shook, and the troops were quite shaken as well. Next morning, Amin walked out in front of the battalion — this was before independence, remember, and he was really just a senior NCO — and told the troops ‘Mungu (God) is angry. We must walk softly and not anger him further.’

“He then gave the whole battalion the day off, and dismissed them,” Combes said. “It was quite an impressive performance, and he did it completely on his own.”

Amin’s legendary strength was not the product of a press agent’s imagination, either.

Masai – Longonot, Kenya

“One day we decided to playa joke on a fellow who had a car; it was just the right length to fit between two of the columns along the front of the barracks, and we picked it up and placed it there. Six of us took one end, and Idi took the other. By himself.”

When Kenya gained its independence, Combes and the other KAR officers were offered a choice of transfer to the regular British Army, or commissions in the Kenyan Army. Combes chose Kenya, and was dispatched with his troops to the Somali country north of the Tana River.

There, in the land where Lord Delamere first saw his golden country a half-century before, Simon Combes settled down among the elephants and thorn bush to a life of chasing Somali insurgents bent upon detaching the province from Kenya and uniting it with Somalia. He spent most of the next five years in the town of Garissa, serving as intelligence officer to the Kenyan forces fighting the Somali raiders. Like most semi-wartime military postings, it consisted of moments of terror separated by longs stretches of monotony.

“We would have a month of total boredom, then an attack, then another month of boredom,” he said.

It was at that point that Simon Combes discovered painting.

In desperation for something — anything — to alleviate the sameness of garrison life, he began drawing and sketching; in watercolors, he painted the African people and their way of life in and around Garissa, and with his love of wildlife, his art soon included animals as well.

“I got started in oils around 1965; I was at a party and met a girl who painted dogs and horses. She told me there was a commission to be had painting the Masai, so I went out and bought a box of oil paints and some postcards to copy. I sold the paintings for50 pounds each. I couldn’t believe it.”

Back in Garissa, between stints of terrorist-chasing, Combes began painting seriously. By 1969, he had enough for a one-man show at Nairobi’s New Stanley Hotel. It was a sellout.

“The pictures were mostly people or landscapes with people in them. There was only one painting of an animal – a cheetah. I was told then that, if I really wanted to make it as a painter in Africa, I had to do animals. Which was fine with me, since I love animals anyway.”

As Combes’ career as a painter gathered momentum, his career as a soldier was coming, inevitably, to an end. He had taken out Kenyan citizenship, and had attended the British Army’s parachute school at Abingdon in preparation to forma Kenyan airborne regiment, which he eventually commanded. One by one, however, the other white officers retired or resigned. By 1974 Combes was the last white soldier in the Kenyan Army and anxious to call it a day. At the age of 34, he resigned his commission and became a full-time painter. It was not exactly a shot in the dark. By that time, Combes’ income from painting was greater than his military salary anyway, and he was gaining acceptance in the United States, the largest market in the world for wildlife art. At the Game Conservation International (GameCoin) convention in San Antonio in 1972, all ten of his works on display were sold.

Around 1980 he moved his family, at least temporarily, back to England.

The Crossing – Wildebeest Migration (detail).

“There were a number of reasons. First, selling my work to tourists, I felt I was living in an unreal world. People on holiday tend to buy things they wouldn’t touch, otherwise, so I did not know, really, how well I was doing. I needed true competition and true criticism if my work was really going to get any better,” he said.

“Then, there was the fact that my wife is English, and my two kids (now aged 21 and 18) were in school there.

“And it was just simply more convenient. I was halfway between my major market (the U.S.) and my research (Africa), and it was just so bloody nice to be able to walk down to the corner and buy paint when I needed it, instead of having to order it and wait for months for it to get there. People don’t realize how remote Africa still is in many ways.”

Not that he had abandoned Kenya, by any means. After leaving the army, Combes took out a professional guide’s ticket, and now takes out two or three photographic safaris every year for the firm of Ker and Downey.

“It works out very well for me,” he says. “I earn a bit of money, I get out into the bush, I sell a few paintings, and I start a few paintings. And I get to spend the winter months in Africa.”

Combes has been best known for his highly-detailed, realistic wildlife paintings, particularly of the big cats, which he says “I love more than any other.”

His painting style was significantly influenced by two factors. One is the fact that he is almost completely self-taught; the other is his friendship with David Shepherd.

The two met in 1969 at Combes’ first show in Nairobi, and Shepherd advised him then that if he wanted to really get anywhere, he would have to paint full-time. Shepherd’s influence has gone beyond pragmatic advice, however.

“I think my realistic approach has been almost a conscious thing, to be different than David,” he said.

“As well, for the longest time I was reluctant to paint an elephant, even though I really like elephants, because David Shepherd is the preeminent elephant painter today.”

Needless to say, Combes has overcome that block, and is now recognized as a fine elephant painter himself.

His work, however, is tending away from large portraits of animals towards painting African landscapes with animals in them. His Wildebeest Migration is a magnificent piece which causes old Africa hands to swoon, so realistic is the rendering, not only of the animals, but of Africa itself.

Although he does mostly wildlife, Combes is fascinated by human faces and loves to paint portraits. Already, he has achieved some renown in that area: when he was attending Staff College in England in 1969 as a Kenyan officer, he was commissioned to paint a portrait of the Prince of Wales. The portrait now hangs at the College.

“In the last year I have done three paintings of the Masai, one of which I’m releasing as a print in March,1989,” he said. “So 1 am branching out a little.”

Combes is represented in the United States by The Greenwich Workshop, which held a one-man Simon Combes show in 1986. Greenwich is planning another, to be held in Carmel, California, in 1990. To date, it has published about a dozen Combes prints, mostly of the big cats, and in mid-1989 it will release the first book of Combes’ work. The book will include reproductions of 60 of his paintings, and Combes is writing the 32,000-word text.

Since the United States is his largest market, it is only natural that he has considered relocating here. Right now, however, Simon Combes has no intention of doing so. He remains a Kenyan, if not by birth, then at least by upbringing, inclination, and outlook.

His work as a guide has given him a close, insider’s view of what is happening to his country, and to the animals there.

Lions survey their domain in An African Experience.

Kenya has one of the highest rates of population growth in the world; the population has doubled since independence, when it was about ten million people, and is expected to hit 26 million by the 1990s. Anyone who saw Nairobi even 15 years ago would hardly recognize it today. Pressure on the animal population, from both poaching and agriculture, is enormous.

If Kenya’s game is to be preserved, strong action has to be taken, and Combes has decided views on what that action should be.

“I believe the only way to protect the animals in the long term is to privatize the parks, but give the government a significant holding in them,” he says. “I think that’s the only answer.”

The country has significant problems, there’s no doubt about that. Still, I love to go back there. I like to go where there’s no horses, no people, no hedgerows. I love looking at places where man has not left an imprint.

“That’s Kenya. It’s still home, and I love it.”

Wherever he is, Lord Delamere is smiling.

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now

Michael Sieve is widely hailed as one of the America’s foremost painters of wild animals. Sieve has spent more than 40 years seeking inspiration in the natural world and channeling it into captivating images that can now be found in private and public collections around the world. Buy Now