From the 2008 May/June issue of Sporting Classics.

The locals called them maral, but elk will do. Some bulls roared like red deer. Plenty whistled and squealed like bonafide Colorado elk. Some carried classic 6×6 antlers. Others paraded clusters of crown points, the style that inspired the spiked crowns of Kings across Europe and Russia. Maral, elk, stag . . . take your pick.

“There! And there. And another over there!” We were, after a small verbal scuffle, finally out of the noise and stink of the vehicle, the gaseous “Russian Jeep.” My guides, who were used to driving Soviet politburo fat cats to their game, wanted to keep motoring, knowing they would eventually bounce and sputter their way to a bull. I wanted out.

“I didn’t fly halfway round the world to shoot an elk from a truck!” I said. But they didn’t understand English any better than I understood the Russian they tossed back. Except for their shakes of the head, the rolling of the eyes. And the “nyets.”

“This crazy American,” they were probably saying. “He wants to play cowboy. Wants to be the big hunter stomping around the woods. He wants to do it the hard way. Don’t be stupid, Americanski!”

Here the big one shifted his Kalishnikov to his other shoulder and the shorter one blew a pall of smoke my way. “Why wear yourself out? We will eventually drive to a big bull and you can shoot it from the truck!”

“Nyet!” I said. Good Russian word, nyet. Conveys a lot of emotion. Forceful. Decisive. “Nyet. I walk. You can stay here and smoke your cigarettes and nip your vodka. I came to hunt. And I will hunt. Right Betsy? Betsy?”

My little blonde bride wasn’t exactly cowering in the back of the bus, but she was definitely hanging on the fringes.

“You be the bad cop, I’ll be the good cop,” she said, holding up both hands and smiling at our guides. But she wanted to hike, too, maybe shoot a grouse.

“It’s okay, guys, okay?” She patted one on the arm and shook the other’s hand and rolled her eyes, nodding at me. “Ron just likes to walk. Let’s humor him, shall we?”

Her body language and tone seemed to turn the tide. The guides shrugged. Alexander tossed his rifle on the seat and stayed with the truck. Klondik stubbed out his smoke and led the way into the birch and pine forest of north-central Kazakhstan, former Soviet Republic, home of the famous fighting Kazakhs. Horsemen. Mountain men. Descendants of Ghengis Kahn. Drivers of Russian Jeeps. And soon to be leaders of crazy, hiking Americans.

We hadn’t gone a hundred yards when we heard the first bugles and roars. They were in front, behind, right and left. Everywhere. I hadn’t heard so much ungulate screaming since late September in Yellowstone. If then. I’d anticipated the roar of red deer, not the bugles of elk.

Why didn’t I bring a bugle? I’ll bet I could call them right in, I thought. Of course, I knew why I hadn’t brought the calls. Because our American booking agent told me not to. We would be hunting roaring stags, not bugling elk. Don’t bother with the calls. This was the same character who’d promised us an interpreter, too.

“Damn. How much room would a diaphragm call have taken?” I groused. Oh well. There was enough bugling that we could simply stalk the musicians. “Let’s go.”

A few yards farther, the vehicle still visible in the background, we spotted our first Asian elk or red deer or whatever it was. It walked over a rise in a meadow near the edge of the forest, bugling like an elk. Parading 6×6 antlers like an elk. But its hide was more monochromatic, like a red deer.

Klondik hunched and pointed, his eyes wide. This foot-hunting business might work. I leveled the rifle. Klondik poked fingers in his ears, but I didn’t shoot. It was too soon—I wanted to discover more before I shot. More hiking. More looking. More elk. More hunting. More Kazakhstan. Disappointed, Klondik unplugged his ears and headed toward the next boogey woogey bugle boy, the second of dozens we’d eventually see on this Asian hunting ground.

Klondik, the author’s guide.

The abundance of elk compensated for the shortage of food back at the bed and breakfast in town. The rooms were roomy, bright, clean and new. Meals were definitely not in the American tradition of excess. You placed your order during the preceding meal, and that’s what you got. No seconds. Ketchup came on the eggs and pancakes and—I swear—sliced cucumbers, but if you requested some for the French fries, they were all out. These weren’t starvation rations, but neither were they holiday feasts. The dessert menu filled an entire page and you could order any item you wanted, but they would be out of it. Every time.

Several fellows in camp took to buying smoked fish from street vendors. “Relax,” advised North Carolinians Jim, Wes and David, who’d been in camp several days before we arrived. Their infectious humor put things in perspective. “You won’t starve, you won’t get fat. And nothing happens on time.”

That was an understatement. We didn’t even get out of town our first day. The promised guides never showed up. The second day they let us hunt roe deer, but not maral nor even the capercaillie and black grouse that flushed from the forest.

That afternoon they took us for a duck hunt. We sat in hole in the ground between two lakes, neither of which we could see, and pass-shot the dozen ducks that zipped over at 60 to 80 yards.

“This explains why no Russian has ever won the World Duck Calling Championship,” I said.

“And why no one collects Russian waterfowl decoys,” Jim added.

Things brightened the third day when the American agent who’d talked us into this predicament finally showed up, speaking Russian. Thus did we finally get to hunt the mighty stags of Asia.

That a quintessentially All-American game animal such as our beloved elk could be an interloper from Asia didn’t seem right when I first heard of this heresy. But the fossil record and taxonomic research support it. Elk are nothing more nor less than an evolutionary branch of the red deer line of Eurasia—a rich, diverse family represented by the rusa, hangul, Bactrian, sika and sambar deer, among others. Maral are supposedly restricted to portions of Turkey and Iran, so it’s highly unlikely we were hunting pure strains of those.

Given the transplants, reintroductions and new introductions conducted by kings, czars, priests and peasants over the centuries, our Kaz quarry could have been an amalgam of who knows what. Virtually every “species” of red deer/elk can interbreed and produce fertile young, and they’ve done a bang-up job of it in the 250,000-acre reserve where we were hunting. We’d never seen such a concentration of elk. Or red deer. Whatever.

The rolling hills near the Russian border 200 miles north of Astana had been replanted to forest by German prisoners of war. Stalin extracted his revenge on his would-be conquerors via slave labor. The mix of clump birch, pine and grassland were then stocked with game. A private hunting preserve for Communist big wigs. Power to the people. Today, the rich and powerful continue getting favored access. Fewer than a dozen paying tourists were allowed to hunt each season, their fees contributing to the support of the facility. Or perhaps the bureaucrats who control it.

But we weren’t in Kaz to foment political revolution. The country had only recently broken away from Russia. Petroleum exploration was booming. We counted 18 cranes on the Astana city skyline, the nation’s capital. A newly built mosque glowed white and gold near the shiny new airport. Cars, trucks and buses choked the highways—and air. Capitalism was booming. All we wanted was a taste of old-fashioned Asian hunting.

After we let the first 6×6 bull walk, we still-hunted within easy range of five more, each sporting five to seven tines on heavy, but short main beams, and each tending one to four cows. Slipping past those cows proved the bigger challenge, but so long as we froze when they looked and moved slowly when we stalked, we avoided spooking them.

Crows, ravens and magpies gave us wide birth or virtually ignored us, but the surprise departure of black grouse and capercaillie left us shaking, particularly when they flushed as we sneaked close to browsing elk. One capercaillie, the world’s largest grouse, launched from an overhead pine and circled us twice within easy range of Betsy’s 20-gauge autoloader, but Klondik forbade its firing for fear of spooking the bull roaring just ahead. For this sacrifice, Betsy was rewarded with the sight of a mature 5×5 dead from a recent battle, a tine puncture in its side.

Bulls were so abundant and competitive that we were rarely beyond sound of one or more until mid-morning. By two o’clock they were at it again in sunshine or cloud, rain or snow. In late October, at roughly the latitude of Grand Prairie, Alberta, Kazakhstan seemed ripe for snow.

“Snow,” I said on our fifth morning as Klondik drove to a fresh location in the forest. “Snow.” I pointed out the windshield and mimed falling flakes with my fingers. “Schnee in German. Ins Deutsch.”

Our guide perked up. Nodded. “Snik,” he said.

“Snik? Russian for snow is snik?”

“Da. Snik.”

“What’s it in Kazakh?”

“Kazakh ees karld. Karld.” And just then a line of wild boars flashed past, dashing gray and hoary into the woods through the swirling karld. A few miles farther, we, too, ventured into what was becoming a small blizzard, a rising wind sending the snik nearly horizontally into the trees.

This day we had a secret weapon: an ethnic German, a descendant of one of Stalin’s WWII slaves, with a crude trumpet. No valves. Just a length of flared tubing and a mouthpiece and the ability to blow it. This was in answer to my previous day’s request for an elk bugle. Instinctively, I started to offer to blow the instrument myself to save the man the trouble of hiking along, but caught myself. This was his chance to shine, to show the American what the local boys could do. And do it he did.

When we heard the first elk of the afternoon, the German Russian cut loose in imitation and here came the bull. Out of the forest, down a draw and up the grassy slope where we crouched 50 yards away. The six-pointer’s brow tines were wonderfully long, but the tops short. I wanted to shoot for the trumpeter’s sake, but knew we could do better. And we did, bugling up the same 6×6 plus three raghorns. With the swirling snow as cover, we stalked three more spikes and raghorns, one 5×5 and a good 6×6 with a deformed left antler.

Betsy was pleading with me. Shoot the damn elk already.

By our second-to-last day I was the only hunter in camp who hadn’t taken a bull. If we hoped to dirty the shotguns and collect a few grouse, I’d have to get this bull out of the way. “First good 6×6 that comes along,” I promised Betsy, having little doubt we’d get the chance, given the many we’d already seen, none appreciably larger than the others.

The biggest bull had controlled a dozen cows, a big harem in those woods. Betsy and I had tiptoed within bow range of him. That animal wore a total of 14 points, yet wasn’t much more impressive than the better 6x6s we had been seeing.

“But I want crown points, too, so maybe not the first 6×6 I see. First good one with crowns, okay?” Betsy sighed and glanced longingly at her shotgun.

Of course, the first game we moved were five black grouse that rocketed from snowy forms in the grass before the forested ridges. The snow holes were filled with the night’s droppings. But red deer were roaring and bugling just ahead. Shhh.

Klondik cocked his head and listened carefully before heading toward the lowest pitched bugler. It was just a fat 5×5. He headed away from three high-pitched bulls and we hiked nearly an hour before hearing another bass growler. Klondik was attracted to the low-pitched growlers, but I never found them to be consistently larger than the more elk-like squealers. We hurried ahead to check this one, crossing the only stream we’d seen the entire hunt and flushing several more grouse.

Betsy was pleading with me. Shoot the damn elk already. Fresh tracks in the snow. Out of the trees. Into a meadow. We followed. Up a hill. Around a ridge. And then a roar, close and raw and wet. Tines bobbing above the snow, dark, almost black, heavily crowned. A cow stepped from a low swale. If the bull followed . . . I raised the light rifle, watched the antlers rise until a dark head resolved above the snow, then a neck, wet and matted. Then slightly paler sides, a broad shoulder rippling, the crosshairs on it, the trigger breaking into recoil, a glimpse of the bull absorbing the hit, running, disappearing over the rise.

“Dead. Kaput,” I said to Klondik’s questioning eyes.

“Kaput?”

“Dah.” Pursing my lips slightly, wrinkling my nose, sniffing, confident, nodding twice. All in a day’s work. “Kaput.”

The hold had been good. The shot was good. I had no doubt. Yet that gnawing little rodent rattled its cage deep within. I ignored it. “It’ll be lying dead just over the hill.”

At 150 paces we found the spoor, a light spray of blood beyond. Then mud, grass and roots splayed across the snow. More blood. A tattered ribbon of red. And there the bull. Dark, wet, dead in the snow. Huge and hot and steaming and bigger than any red deer I ever imagined. This was good.

Klondik slapped my back. Shook my hand. I think he didn’t quite believe I’d finally shot. This wasn’t the biggest bull we’d seen, but big enough. We’d hunted long and hard and well and the Russian Jeep was parked far away. We could hear ravens croaking, woodpeckers tapping, even karld hissing against the dry weeds where the bull lay. This was hunting.

Read more of Spomer’s work at RonSpomerOutdoors.com.

Be sure to sign up for our daily newsletter to get the latest from Sporting Classics straight to your inbox.

Photos by Ron Spomer.

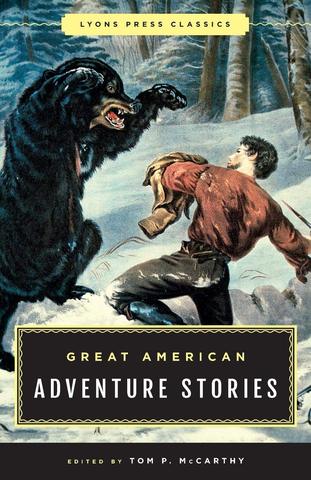

An extraordinary collection of fifteen stories that celebrate America’s unquenchable thirst for excitement.

Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today.

Created for adventure addicts there has never been a more exciting collection of stories that celebrate the indomitable spirit of the American character. Buy Now