The type of paintings I most enjoy are the ones where I look and think, ‘How did he get away with that and still make it work’?

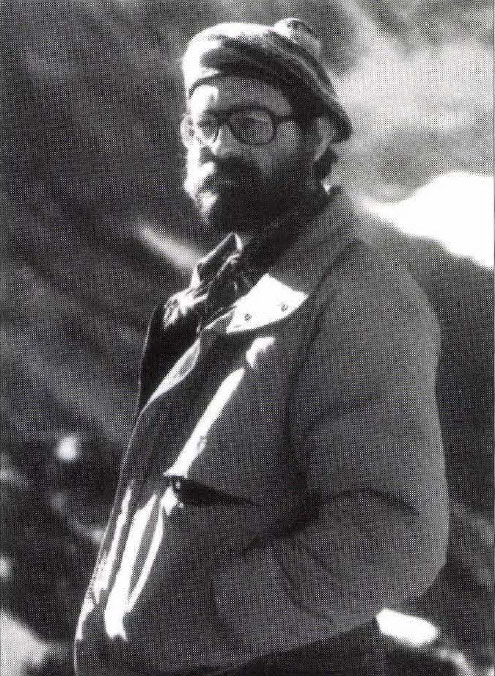

The Artist.

[Years ago,] on a Saturday morning in August, my husband Charlie woke me up to show me an ad in Sporting Classics. Dan Metz was selling the original drawings he’d made for the book, Last Casts and Stolen Hunts: The World’s Best Hunting & Fishing Stories.

“Do you think I dare call him?” Charlie asked. “It’s seven o’clock. Would you like to go out there with me?”

It was my birthday, and I had planned to go on the annual St. Croix Valley Garden Tour. But now I had an opportunity to meet Dan Metz! Garden tour or Dan Metz? I mused, as Charlie picked up the phone.

By the time he hung up, I had eliminated the flower tour. Dan said his place in Delano, Minnesota, was straight out Highway 12, about an hour and a half west of us. We should watch for the yellow pole barn. “We’re the third place on the right.”

Dan lives on the farm where he grew up and paints on the second floor of a frame building down the back lawn from his parents’ house. The oldest of eleven children, he graduated from the local high school, then worked at various odd jobs until he became a draftsman for a small industry in town. But even during his days of loading trucks and driving forklift, Dan always found time to draw and paint wildlife, and by 1978, he was ready to devote himself to his art.

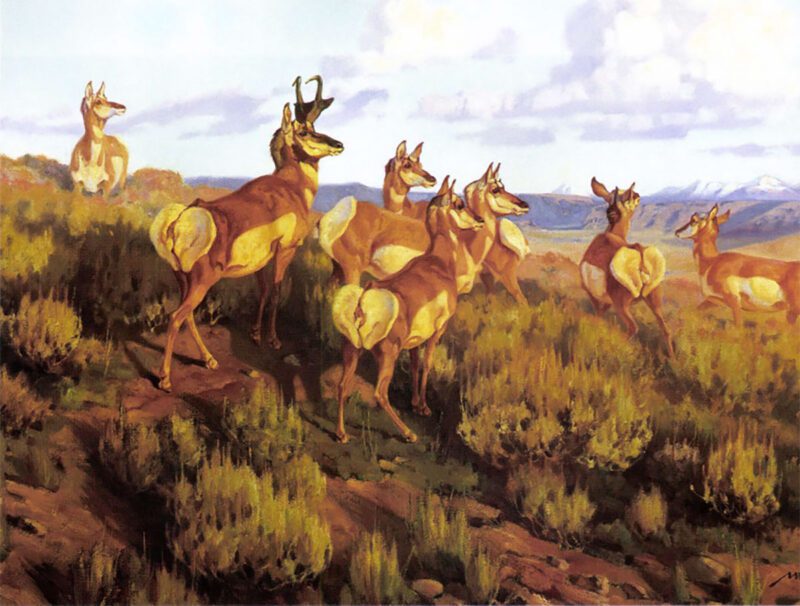

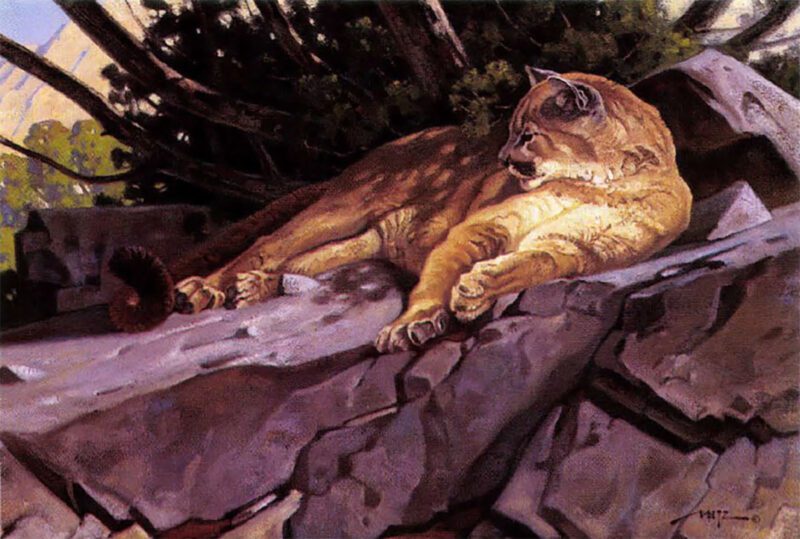

Spooks, 26 x 36.

His studio at the top of a flight of plank stairs is a large, unfinished room; the drywall is up and taped, but the walls are unpainted. There’s an old wood burning stove in the center of the room to keep the place warm in the winter and an air-conditioning unit stuck in one window. Two couches disguised with throws form an “L” on one end of the rectangular room. At the other end, where Dan paints, there’s a large easel, a chair, and a small worktable for his painting paraphernalia. Bookshelves stuffed with art and natural history books line the walls, and the place has the usual clutter associated with an artist’s studio.

Metz is a quiet and unassuming man who reminded Charlie and me of Philip R. Goodwin. A dark-haired bachelor with a bushy mustache, Dan bears a slight resemblance to the great artist/illustrator. More to the point, he paints every bit as good as Goodwin did, and exhibits the same preference for painting North American big game.

Unlike Goodwin, Metz is still largely unsung. He doesn’t have a huge following, and his sales are sometimes slow. He had taken on some book illustration to bring in a little money, he said, but not many people were interested in his pencil drawings. We could pretty much have first pick of his pieces from Last Casts and Stolen Hunts.

How lucky could we get! My birthday was getting better by the minute. We had planned to buy just one drawing, but after much deliberation, we picked out two. Charlie had to have an illustration of a fisherman that had accompanied Frederick Pfister’s tale, “Dead Fish Tell No Lies.” I picked a winsome drawing of a lovely little burro for Jack O’Connor‘s story, “We Shot the Tamales.”

Few artists can draw as well as Dan Metz; indeed, even fewer can match his skills with the various sketching media, from pencil and pen-and-ink to scratch board and Conte crayon. An ability to draw is basic to being a good painter, he will tell you, and “a lot of artists cover up poor drawing with detail.”

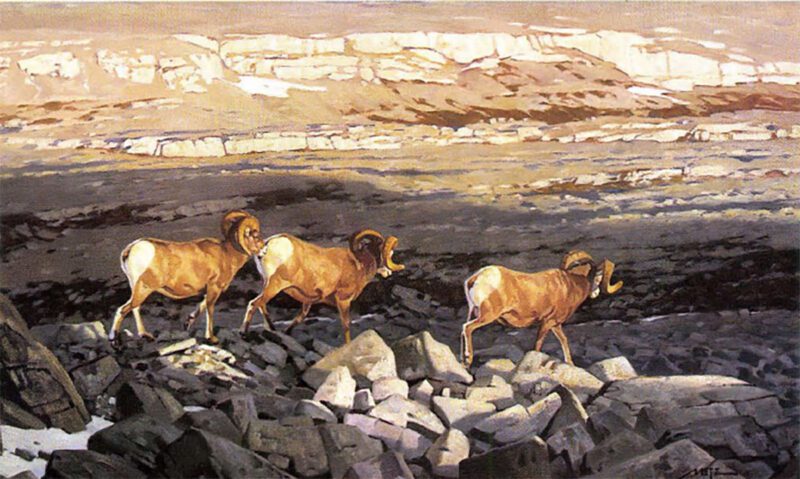

Untitled, 26 x 32.

Over the years, Metz has illustrated a number of books, including two for the great nature writer Sigurd Olson. He has also amassed a valuable logbook of sketches which he uses as reference for paintings. He showed us hundreds of carefully rendered pencil drawings filed in large folders by species. I asked if we could buy one of these, too, but Dan said he doesn’t sell his sketches, that they are his “soul,” He ended up giving me one which now hangs in our front hall.

Each autumn, Dan Metz packs his duffel and heads west to photograph and sketch big game in the wild. His favorite species is bighorn sheep. “They’re very friendly,”’ said Dan. “One year I spent two weeks with a band of rams. I’d get up every morning, find the rams, and spend the day with them. They don’t do much during the day except eat and sleep and chew their cud. After four or five days, one ram came over and plopped himself down right next to me. It’s hard to get pictures of sheep in the kinds of places you want to paint them. They’re usually down lower on the mountains. If you hang with them, you can get good stuff.”

On another trip west, he had a chance meeting with noted sculptor Bob Scriver in Montana. It was during a snowstorm, and Dan had driven about as far as he could go, so he stopped in a cafe. A local man struck up a conversation, asked him where he was from, what he was doing, that kind of thing. The next thing Metzknew, the man was introducing him to someone in a grungy cowboy hat, instantly recognizable by his sporty goatee as Bob Scriver.

“Do you like Carl Rungius?” Scriver asked him. You bet he did, responded Metz, who considers the German-born artist of his mentors. So Scriver took Metz up to his house and showed him his Rungius paintings. The men became good friends and some years later, Metz did two drawings for Scriver’s book, The Blackfeet. Artists of the Northern Plains.

During our visit, Metz showed us some of his paintings of “BHMs,” as he calls them — big, hairy mammals. Moose, elk, deer, pronghorns, grizzlies and the like have been his major focus for the past 17 years. The last painting he did of an avian species — a beautiful oil of a woodcock flushing up over a riverbank — was quickly accepted for the 1981 Birds in Art exhibition at Leigh Yawkey Woodson Art Museum in Wisconsin. “I’ll do another bird painting — someday, of swans; they’re big enough to appeal to me.”

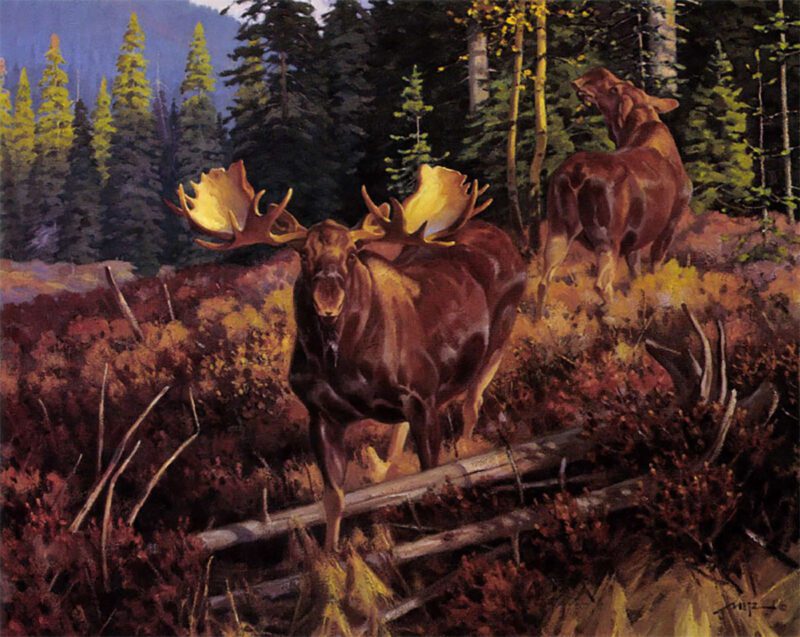

Unchallenged, 24 x 30.

Subject matter is not nearly as important to Dan as the elements that make up a good painting, and he has devoted his life to understanding and mastering every aspect of his art. But when we visited with him that morning two years ago, Dan wasn’t satisfied with his painting. “When I can paint as well as I can draw, I’ll feel good about my work,” he told us.

Charlie and I drove home feeling it had been a banner day. We liked Dan a lot, and felt privileged to have met this dedicated young artist and to have spent time with him. The day was warm and sunny, perfect for a garden tour, but I’d enjoyed that, too. Dan’s mother had shown me her wonderful gardens full of old-fashioned flowers in full bloom.

I was delighted when editor Chuck Wechsler asked me to write this article. By now, I’m a real Metz fan, and I knew I’d enjoy seeing him again. In the meantime, I phoned Dan and asked him for some biographical material. The few magazine articles he sent came with a note explaining that he didn’t have much of this kind of thing, and he’d sort of planned it that way.

“I haven’t sought publicity as I learned from illustrating that once it’s out there, it’s out there for good, and usually in a year or so it doesn’t look so good anymore! Charlie was eager to see Dan’s latest work, so we drove out to the Metz farm together. A few chickens scurried forcover as we got out of the car, and the gardens were as pretty as I remembered them. We found Dan still doing “big, hairy mammals;’ but his canvases now included horses and cowboys.

The Art of Self Amusement, 18 x 26

Dan grew up around horses, and for years he bred and raised them on the family farm. And because he prefers to paint only those animals which he is both intensely interested in and familiar with, it was probably inevitable that he would begin painting horses. He had just come home from a few weeks in Wyoming where he worked on a ranch in Pinedale, about eighty miles from Jackson. “I can ride a little, and once these cowboys find you can ride, you’re working, and if you work, they keep inviting you back,” he smiled. It’s obvious he enjoys the cowboy life, but there’s more to it than that. Metz has set out to capture the cowboy way of life on canvas. “So much of what I’m looking at is history already. Ranchers in that area are the last of a breed. What I’m trying to do is paint the entire cycle. Last year I went out for the branding. This year we drove the cattle to the mountains.

“I like to make a trip west every fall from about the middle of September to the middle of October, but last year and this, I’ve been there in the spring and summer. It seemed really strange to see the Dakotas green.”

The paintings he showed us were truly stunning. I think I can safely say that Metz now paints as well as he draws! At age forty-four, the self-taught artist appears to have hit his stride. He’s always been gifted at composition, but he’s painting with more confidence now and it shows. “It’s starting to go better,” Dan admitted. “I’m starting to solve some of my problems. I used to paint really hard-edged. I’ve been working on that as well as basically just getting the paint to lie down the way I want it to.

“Less is more on the condition that the less is great — I’m still working on that one. But I agree with Jaques [Francis Lee, the great Minnesota wildlife artist who died in 1969] that an artist should never paint more detail than he or she can see. I’m trying to train myself to paint more like I see than what the camera sees.

“Every artist has limitations, of course, some more than others. Taking chances and experimenting is the only way to break down those limitations. I’m always trying to improve, but I’ve also learned that I’m never going to be satisfied. It’s always a case of the more you learn, the more you find out how little you know.

Late-day autumn light accentuates the polished tines and muscular flanks of a bull elk in Here And Gone.

“My stock answer when I’m asked what I do for a living is, ‘I’m accused of being an artist, but I’ve never been proven guilty’.”

Why, unlike almost every other wildlife artist of any stature, isn’t he doing limited edition prints? In the beginning, Dan said, he made a conscious decision to stay away from prints until his work had reached a certain level that satisfied him. Now, he simply doesn’t believe in this marketing gambit.

“Trying to please the general public is, I think, a little dangerous for an artist. It puts a kink in creativity. You can try to calculate what will sell, but you can’t make those calculations last.

“Artists like Kuhnert and Rungius and Liljefors couldn’t make a living selling prints today. Ken Carlson and Bob Kuhn can’t sell prints. I’m not as loose as any of those guys, but my style is too loose for prints.”

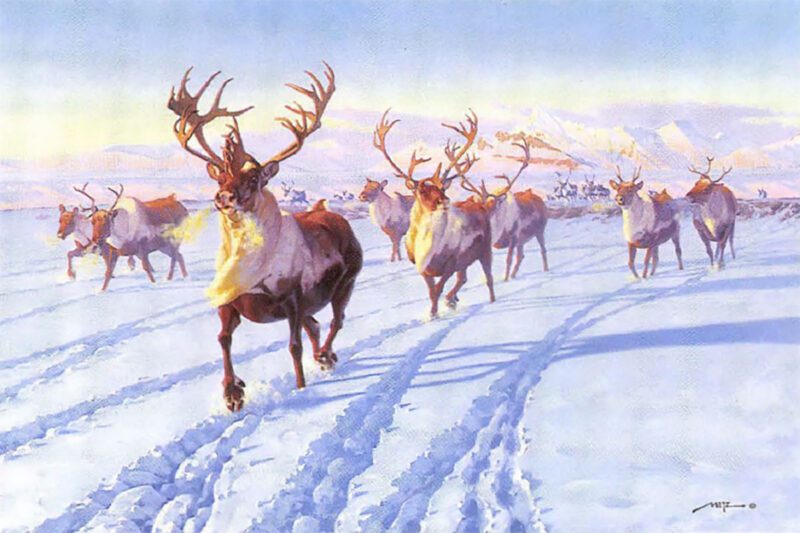

A caribou herd crossing the Barren Ground.

Eventually, our discussion came around to the old debate about wildlife art versus fine art.

“Subject matter has nothing to do with whether a painting is art or not,” said Metz. “It’s irrelevant. What matters is how well you make a picture. Rembrandt painted a carcass hanging in a shed and that was art!”

“So let’s talk about wildlife art today,” I prompted. “Wildlife art, to use the media handle, is realism,” Dan replied. “No two ways about it. And to be realistic, things must be recognizable. Due to man’s intimate knowledge of himself, a painter can depict a human being, recognizable as such, with a few quick brushstrokes. But this is just not so with, say, a moose. Lack of familiarity forces delineation.

“To create art entails a talent for elimination — reduction of non-essential elements down to, maybe not truth, but at least a particular artist’s version of the truth. You’ve got to shape and mold the various elements that go into a work of art into something more than what is set before you.

Timber wolves in A Song to Hear.

“Too many artists copy photographs. My main beef is ‘where’s the picture’? Artists today aren’t making pictures like the old guys [turn-of-the-century artists] made pictures. The type of paintings I most enjoy are the ones where I look and think, ‘How did he get away with that and still make it work’? “On this drive home, Charlie and I talked about how refreshing Metz is. He’s an artist apart, alright. Something of a throwback to an earlier era, with his love of cowboying and the early illustrators, he is also on the road to becoming a 20th century master. Driven by the desire to become the best painter he can be, he’s obviously not in it for the money, willing as he is to accept an almost austere lifestyle just to pursue his dream. You have to admire his guts and determination, and he’s a nice man to boot. A couple of days later, as an afterthought, Metz sent me this passage from Kipling:

When the flush of a newborn sun fell

first on Eden’s green and gold,

Our father Adam sat under the tree and scratched with a stick in the mould;

And the first rude sketch that the world had seen was joy to his mighty heart.

Till the Devil whispered behind the leaves.

“It’s pretty, but is it Art?”

Now if it’s a Metz painting you’re talking about, you bet.

Editor’s Note: this article originally appeared in the 1995 Sept./Oct. issue of Sporting Classics.

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Buy Now

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Buy Now