If you’re looking for rainbow trout the size of salmon, Crystal Creek Lodge awaits.

Of all the world’s trout and salmon fisheries, none hold a fly rod to Bristol Bay, Alaska. It sits at the eastern most arm of the Bering Sea and is 250 miles long and 180 miles wide at its mouth. Several of the world’s greatest salmon rivers feed the bay, natal waters for millions of fish that return to spawn each year. Because of this, Bristol Bay is a place that lures fishermen from across the globe.

The Bristol Bay watershed produces nearly half of all the sockeye salmon in the world, generating $1.5 billion and supporting some 20,000 jobs annually. It is a natural protein factory the likes of which is unmatched anywhere in the world, and it’s likely that value was hardly contemplated when America purchased the territory from Russia in 1867.

Joining me for four days of fishing is Guido Rahr of the Wild Salmon Center, an Oregon-based conservation organization working to save ecosystems around the Pacific Rim that are vital to salmon and steelhead. Our home base is none other than Crystal Creek Lodge, a Michelin-level destination amid the many fabled lodges found in and around Bristol Bay. It’s located outside of King Salmon and is run by Dan Michels, a veteran of the premium sporting travel business.

After a short ride in one of Crystal Creek’s immaculately restored DeHavilland Beaver float planes, we are standing knee deep in a small, trout-rich tributary that feeds into Lake Iliamna, the largest body of freshwater in all of Alaska. In addition to its sea-like size, the lake is so clean that you can drink directly from its waters, an unimaginable reservoir of purity. It is emblematic of a state that wears the moniker of “Last Frontier” like no other place could, pristine and largely untrammeled by the hand of man…for now.

Guido Rahr of the Wild Salmon Center enjoys the fight of a rainbow at Alaska’s Brooks Falls. Photo by John MacGillivray – Dorsey Pictures

The lake also is home to salmon sized rainbows, the beasts that migrate out of Iliamna’s waters each autumn to gorge themselves on salmon roe that turn these tributaries orange as the fish spawn and die. In the process, they release their nutrients and feed an entire ecosystem from the giant brown bears to the wolves to eagles and fox and all manner of species in between—even the trees depend on the nutrient load carried upstream by the salmon. These arteries of fish are the basis of a remarkable natural story, one where the interdependence of species and habitat is intricate. Remove any one piece of the food chain here—especially the salmon—and this ancient natural theater becomes a house of cards.

“Try the seam just a little farther out,” says guide Ryan Friel, as if he knows a secret that the river is about to share with me.

My cast hits the water as instructed and a couple of seconds later I hook into a 30-inch plus rainbow trout, the kind that are legend in these parts. Three more jumps later and he pops off, discarding my offering like a bucking bull throws a rider.

“Son of a…I thought that was a salmon,” I say in disheartened disgust at having wiffed on a chance to catch one of the area’s rainbow warriors, a leopard printed beast that becomes addictive for fishermen once they experience the narcotic of the tug of a 30-plus-incher. Instead, my line dangles in the water like the punchline to a bad joke…one in which the joke is on me.

Between casts I’m able to catch up with Rahr who has been on the front lines working to save this unique ecosystem from a proposed copper and gold mine at the headwaters of Bristol Bay. Plans to develop Pebble Mine have sent ripples throughout the conservation and sporting community unifying sportsmen, manufacturers and environmental organizations like few other conservation issues of the last half century.

In addition to its dramatic, large log construction, Crystal Creek Lodge, with towering beams and stunning views, is perfectly positioned to offer a wide variety of Bristol Bay’s best angling from several species of salmon to giant trout to Dolly Varden and char. A trio of DeHavilland Beavers that appear newly minted, warm up each morning to transport guests to the far corners of the concession depending on daily fish movements and angling desires. Then there is the food…a Michelin experience served daily, using locally grown, caught and sourced ingredients. Arrive here and you have landed atop the angler’s food chain.

The salmon are far more than protein providers, however, as they also serve as what biologists like to refer to as keystone species, canaries in the proverbial coal mine. As goes the salmon, so goes the rivers and the oceans…and ultimately us. Without the salmon these rivers would be little more than sterile drainages, for the fish are to coastal Alaska what the great caribou migrations are to the tundra, annual gifts of life to the entire ecosystem.

“The salmon provide massive pulses of marine nutrients gathered in the ocean and then they deliver them into the Bristol Bay ecosystem as they migrate to spawn and die,” says Rahr.

The next day we board a Beaver with Michels in the cockpit. Our destination is the famed Brooks Falls, the iconic bear playground where behemoth browns sit like Labradors waiting for treats of salmon to jump upstream and into their jaws. It’s the postcard view of the state celebrated in every Alaskan travel campaign.

At first, fishing amid the bears seems a nervy proposition, the world’s largest land carnivores with their trash-can sized heads just 50 or 60 yards away. As I hook into my umpteenth 25-inch, super-charged rainbow, I watch a trio of brown bears on the other side of the river as they take notice of the splashing, triggering a Pavlovian response from the 1,500-pound carnivores. These are fish bears, growing three times the size of their interior grizzly cousins who do not have the benefit of the protein-rich salmon on which to gorge themselves. Soon the bears ignore the splashing trout and return their focus to the massive school of salmon under their noses.

“These rainbows are a special breed,” says guide Ryan Burge, “they’re hotter than you’ve ever seen other rainbows.” Translated, they fight substantially harder than their kind in other waters.

Soon Rahr begins fighting a fish pushing 30 inches, glancing over his shoulder to take inventory of the bears in the vicinity, as he marvels at the health of this fishery.

“It used to be like this up and down the coast of the Pacific Northwest,” he says. “Now we’re spending hundreds of millions of dollars to try and bring back what once was. Here we can preserve what is…a far most cost-effective approach.”

Guido Rahr is all smiles as he’s about to release one of the giant rainbow trout for which Crystal Creek is famous. Photo by John MacGillivray – Dorsey Pictures

The headwaters of the Nushigak and Kvichak—our next venue of the trip—is where the proposed Pebble Mine would be located. When copper and gold are mined, the remaining tailings sometimes leach toxins into the watershed. Moreover, this is one of the most tectonically active zones in all the world, so expecting an earthen dam to hold back toxic waste water seems a fool’s errand to most conservationists, for there’s little hope that such a structure will last long term. Furthermore, Alaska experiences upwards of 10,000 earthquakes each year, more than 10 percent of the annual global total.

“If Mother Nature was to design the perfect trout stream, it would be the Kvichak,” says Rahr. “It has a migration of giant, ghost-like trout that come out of Iliamna and act like steelhead.”

The last day breaks windy and rainy, conditions only suitable for bold pilots, not ones still among the living. What’s there to do? Simply load a boat and head down river on the Naknek, the home river of the lodge. Within minutes, we are landing what seem, for all intents and purposes, to be steelhead. These are yardstick long rainbows that have grown humongous in the lake but can’t resist the abundance of salmon eggs in the Naknek where they feed and grow even larger.

“There’s nothing like the productivity of Bristol Bay…it is simply one of the most miraculous occurrences in nature,” says Rahr. And the only way to insure something that’s invaluable is to protect it.

Because there’s no replacing it.

This article originally appeared in Forbes. Follow Sporting Classics TV host Chris Dorsey at Forbes.

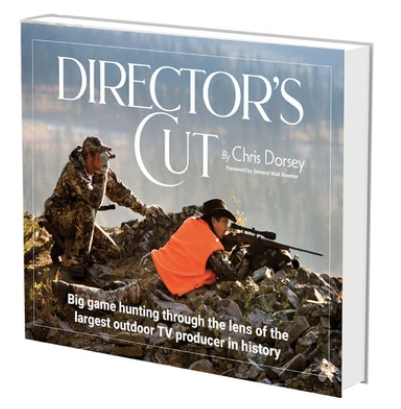

The World Of Sporting Literature Has A New Classic from one of the planet’s most widely traveled hunters. Director’s Cut…Big game hunting through the lens of the largest outdoor TV producer in history, is a book and film production more than 15 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of big game hunting.

The World Of Sporting Literature Has A New Classic from one of the planet’s most widely traveled hunters. Director’s Cut…Big game hunting through the lens of the largest outdoor TV producer in history, is a book and film production more than 15 years in the making. Author and Executive Producer Chris Dorsey, along with a team of the world’s best sporting life photographers and cinematographers, embarked on expeditions to distant corners of the globe to create an indelible portrait of big game hunting.

Dorsey has spent the past 25 years investigating and chronicling the animals, people and unforgettable places home to remarkable big game hunts while producing nearly 60 outdoor adventure television series. In the process, his teams amassed a library of more than 100,000 hours of HD footage and nearly 150,000 photographs, making Director’s Cut (the book and DVD) an unmatched celebration of the world of big game hunting. Pre-Order Now