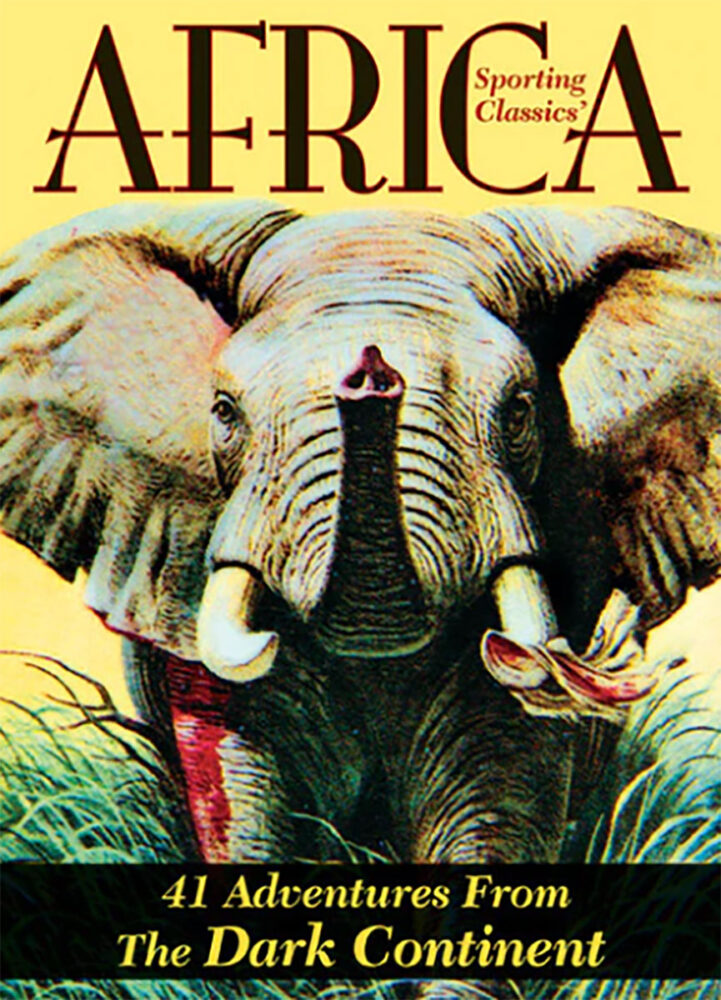

The continent of Africa has been viewed with a mixture of fear and greed for the past 500 years…

“The wild creatures I had come to Africa to see are exhilarating in their multitudes and colors, and I imagined far a time that this glimpse of the earth’s morning might account far the anticipation that I felt, the sense of origins, of innocence and mystery, like a marvelous childhood faculty restored. Perhaps it is the consciousness that here in Africa, south of the Sahara, our kind was born. But there was something else that, years ago, under the sky of the Sudan, had made me restless, the stillness in this ancient continent, the echo of so much that has died away, the imminence of so much as yet unknown. Something has happened here, is happening, will happen-whole landscapes seem alert.”

Roaring Lion – Wilhelm Kuhnert

Peter Matthiessen’s words, in The Tree Where Man Was Born, go to the very heart of the African experience. Twentieth century man, by setting foot in Africa, can telescope centuries of evolution in a day. Nowhere else on earth can one become one’s ancestor, standing on the vast grassy savannas just as primitive man once stood, watching the processions of wildebeest and zebra, fearing the lions and leopards in the bush and wondering if he will survive the night to hunt and feed another day.

The continent of Africa has been viewed with a mixture of fear and greed for the past 500 years, ever since the Portuguese set out upon the oceans to find a route to the Far East for spices and silks. Coastal Africa remained the only known part until the 19th century. Then, a great surge of scientific and commercial exploration penetrated Africa’s “heart of darkness” and brought it to the forefront of the European imagination. Africa was the hope of industrial Europe looking for raw materials, and colonies sprang up as England, Germany, Portugal and Holland raced to divide the spoils. It was the great romantic vision, and many an adventurer set off to discover his own destiny.

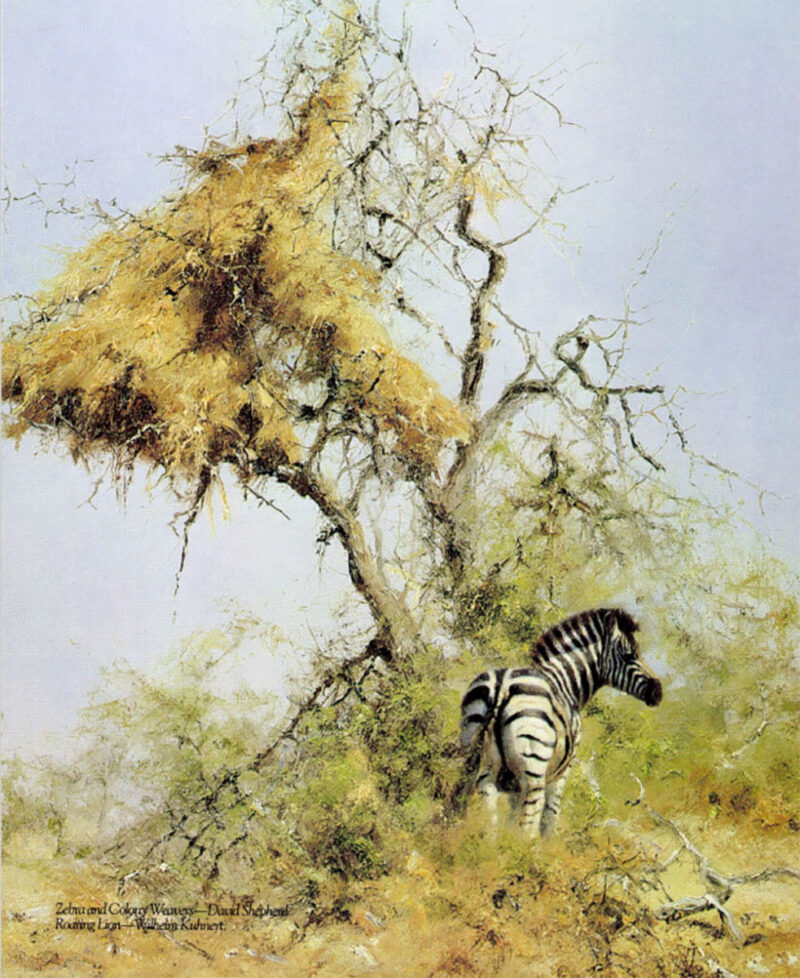

Zebra and Colony Weavers – David Shepard

Perhaps the first accurate image of Africa’s wildlife came out of South Africa in 1840. Captain William Cornwallis Harris, a young engineer employed by the East India Company, made a trip to England’s Cape Colony, as it was called in those days. His enthusiasm for the country and for hunting, combined with a solid artistic ability and knowledge of natural history (primitive as this science was then), produced a most elegant and vibrant portfolio of South Africa’s animals. Harris’ description of this undertaking gives us a perspective 180 degrees different from that of Peter Matthiessen:

“All the first sketches of my drawings were commenced either in the open air with the animal before me, in the scene of slaughter; or under the shelter of some neighboring bush, and were completed upon my knees in the wagon, often amidst rain and wind. The indolence and apathy of our Hottentot attendants who resemble the wild beast as nearly in habits as in features, invariably obliged me to carry the appliances far drawing as well as the embryo portraits upon my person; and that they should have been preserved to assume their present shape will probably excite surprise, when I add, that I often wended my solitary way from the sporting field, not only encumbered with my weapons and hunting gear, but also laden with venison, and staggering under the weight of the ponderous trophies which had fallen to my rifle.”

Harris’ expedition was in the tradition of natural history exploration–collecting specimens, recording observations of plants, animals, insects, geology-whatever came under the investigator’s eye. Such ventures have continued up until the present day, largely under the auspices of the world’s great museums. Often, collectors of specimens were accompanied by artists who recorded vegetation and landscape for later habitat groupings. Accuracy and detail were the prime objectives for these artists, but on occasion, men of exceptional talent, such as William R. Leigh, Louis Agassiz Fuertes and Terence Shortt, produced work of enduring aesthetic appeal, as well as scientific interest.

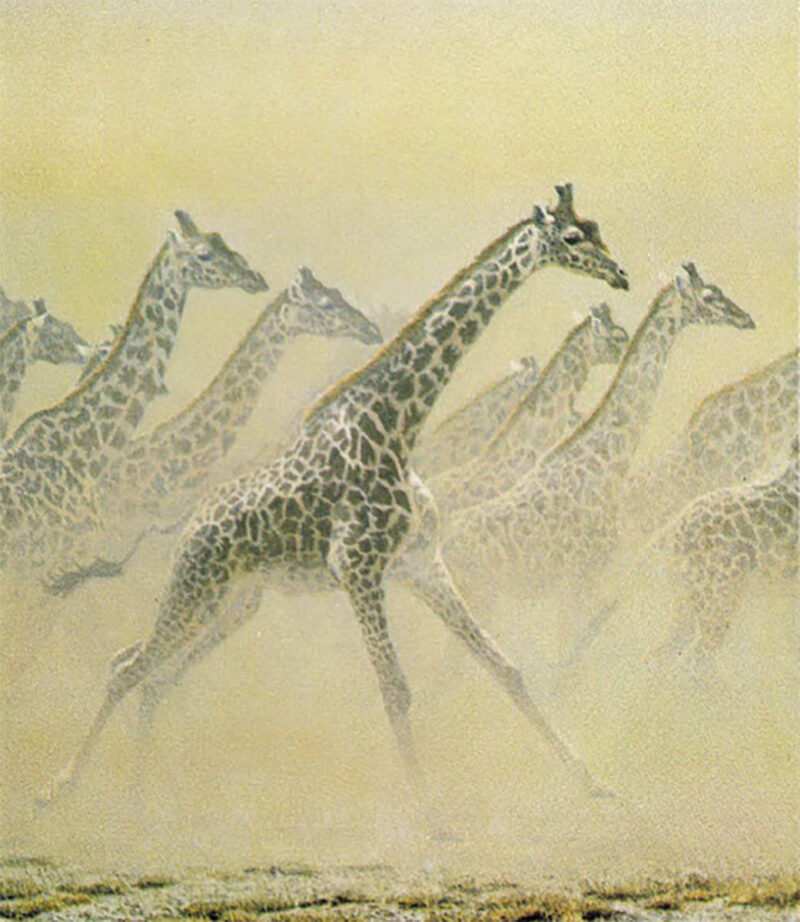

Galloping Herd – Giraffes — Robert Bateman

Toward the end of the 19th century, one lone artist set off on a voyage to Africa. Wilhelm Kuhnert made his first expedition in 1891, at the age of26, just twenty years after Stanley’s discovery of Livingstone at Lake Tanganyika. Embarking from Hamberg, Germany, Kuhnert carried trunks of tinned provisions, medical supplies, and his paints and sketchbooks. When he reached Southeast Africa (then a German colony), he hired natives as porters and guides to take him into areas where he could study and hunt game for months.

Kuhnert was the first artist to travel to Africa for the express purpose of studying wild animals in their proper environment. Today, a handful of artists have made trips for the same reason, however, back in 1885, when Kuhnert was a student at the Berlin Academy of Art, no one thought it necessary to do such a thing. His professor, Paul Meyerheim, considered a fine painter of wild animals in his day, advocated the use of zoo animals. Then he would say to his students, “sketch out the expanse in charcoal, strew somes and here and there, and the most beautiful desert is soon to be done!” Kuhnert found this approach unacceptable.

It was not, however, totally unacceptable to Kuhnert’s contemporary, Richard Friese, who became one of Germany’s most celebrated wildlife painters. Friese, like Kuhnert, was drawn to the romance of African subjects. He painted lions to satisfy his royal patrons, but never got to see one in the wild. He was even offered a tree trip to interior Africa with the German explorer, Nachtigall, but declined because he was too busy painting a commission of, what else, a lion. He later made a trip to Syria to see lions, but instead saw only lots of desert, some wadis, and a few jackals.

African Amber – Lioness Pair — Robert Bateman

Kuhnert and Friese came out of the European painting tradition of Romanticism-its worship of nature, the sublime and untamed. For Kuhnert and Friese, the animal that symbolized that vision was the lion. Other artists before him had painted lions-Delacroix and Gericault painted numerous versions of a lion attacking a horse. To the Romantics, the horse represented grace, elegance, refined beauty being savaged by the ferocious, unpredictable violence in nature embodied in the lion. Not that lions naturally go around attacking horses, but the Romantics weren’t interested in accuracy-they wanted vehicles to express emotional content.

Kuhnert, however, was interested in accuracy-not just the scientific variety, but the living, breathing, active subjects that he found. Their forms and habits interested him, and as a hunter, he came to know these well. But the drama of their existence also captivated him. As he wrote in his book, In the Land of My Models, “Here the struggle for survival is waged . . . and this is clearly stamped on the outward appearance of wild things; it gives them an elemental power and unlimited freshness of life. What lives and loves here is in the most exuberant and wildest health. The king of animals, man, seems so weak and undeveloped next to these warriors!”

A romantic viewpoint, to be sure, but Kuhnert’s own energy and enthusiasm comes out in his unforgettable portraits of African animals. His buffalo are massive, wary, unpredictable and always menacing in their hulk and in their own expressions, particularly the eye. Buffalo have keen eyesight and, despite their weight and size, are very fast — facts that Kuhnert, the hunter, knew never to underestimate, even though he constantly endangered his own life by waiting until the very last minute to shoot a charging animal. This was so he could fix the image fully in his mind to be translated later onto canvas.

Grants Gazelle — Wilhelm Kuhnert

It was the lion that especially captured the spirit of Africa for him; tawny, sinuous, powerful. He painted more of them than any other subject, earning him the nickname “Lion” Kuhnert. His lion pairs are symbols of matrimonial togetherness-grooming, stretching, hunting, dozing-a notion that would have been hard to dispel in this inveterate romantic even had George Schaller’s definitive monograph on The Serengeti Lion been available to him. It was not for Kuhnert to have the magnificently maned male stealing his food (mostly from lionesses) and sleeping 20hours a day. Kuhnert’s lions are eternally noble, defenders of their prides and domain. The last painting he completed before his death in 1926 was that of a male roaring at dusk.

However romantic Kuhnert was in attitude, he was a realist in his painting. Like the romantics who preceded him, he venerated the nobility of nature, but like the realists, when he painted he was faithful to what he actually saw. He saw very well. If you squint at his paintings, or stand far enough away from them, you might conceivably mistake them for the real thing-or for photographs. His hand was deft, his draftsmanship that confident. Yet his canvases were not photographically realistic. On close inspection, the linear brushwork is freely executed, with an absence of intricate detail-carefully suggestive, but not literal.

Like Kuhnert, virtually all of today’s painters of African wildlife paint realistically and the best of them study their subject in the field. While none of them paint quite like Kuhnert, neither do they-David Sheperd, Bob Bateman, Guy Cohleach, Bob Kuhn and Keith Joubert — paint like each other. Sheperd may soften the details of landscape for a vignetted effect, but his animals stand strong and clearly defined. Bateman, a realist in the Wyeth tradition, draws us into the animal’s point of view through a carefully structured composition. Cohleach’s versatility ranges from very detailed to very loose brushwork, but whatever style he chooses, his portraits are always powerful and riveting. Drama was crucial to Kuhnert’s vision of Africa, and so it is for Bob Kuhn, who fearlessly captures animal motion in an unparalleled way. Joubert uses shape and texture in a strong, graphic style to express a dream-like vision of his native land.

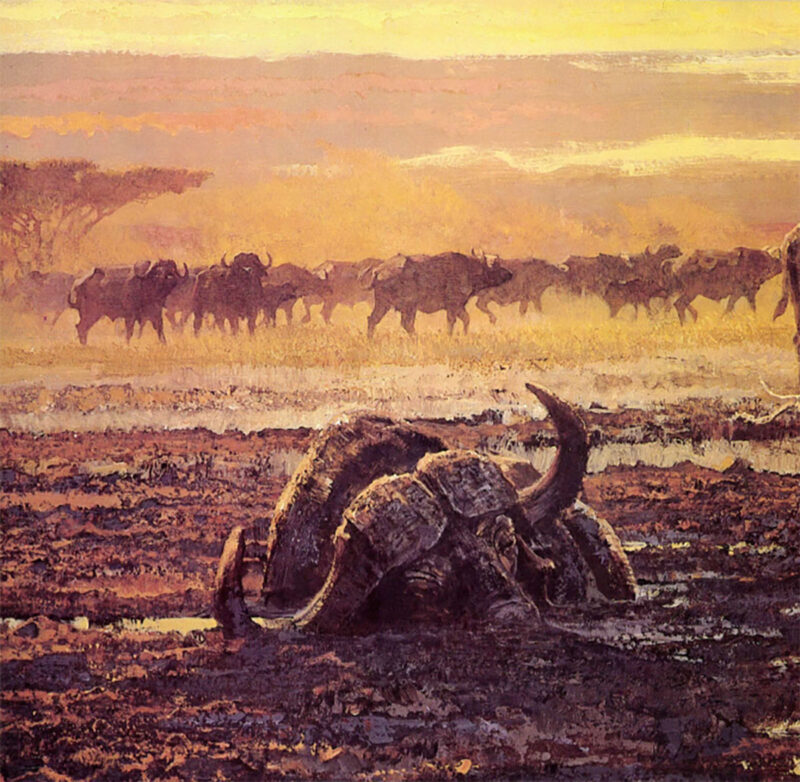

Mired Bull – Bob Kuhn

England’s David Shepherd sees Africa in terms of color. He has been painting its wildlife for nearly 20 years, and has formed strong impressions of its landscape and what appeals to him. In fact, he considers himself a landscape artist, not an animal painter. Of the 22 national parks he has visited, there are four he prefers to know intimately. The Luangwa Valley in Zambia is at the top of the list because it is so unspoiled. Etosha in Namibia is next, then Tsavo in Kenya and Kruger in South Africa. Tsavo appeals for its “lovely red earth which makes it unique, ” Etosha because “it is beautiful, dusty grey, very subtle, absolutely glorious and has huge herds of zebra. ” Kruger National Park has its “marvelous variety of everything, scenery and wildlife, although poaching is a problem as it is in the Luangwa.”

“Africa to me is very definitely yellow and broom. I am not so keen on green Africa, the wide-open green spaces of the Serengeti which other artists would go wild about. The Luangwa, in the dry season, goes doom to a trickle. It is an enormous river, flowing into the Zarnbezi. But in October; the height of the dry season, it is a fraction of its normal flood size —the yellow sand, the heat — I love the heat — and dead trees that have been swept doom by the rains of the previous season. These lovely, twisted, sculptured shapes of dead, grey trees, the yellow sand, the broom of the hot, dried up thornbush, and the yellow grass — that’s Africa to me.”

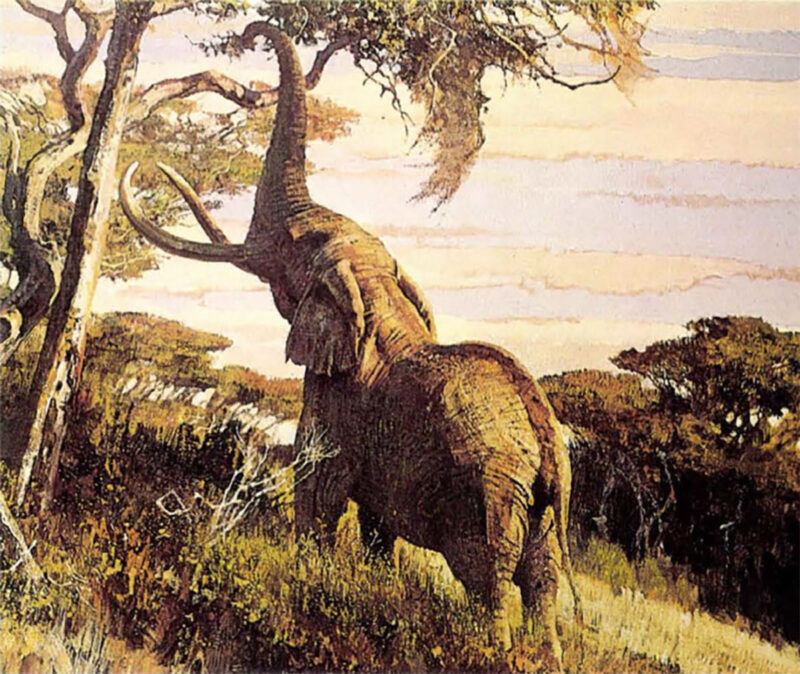

Shepherd’s Africa is not one of carnage and predation,and he himself is not a hunter. In fact, he is unabashedly sentimental about its creatures, particularly elephants. “Whenever I see an elephant, I think of a steam locomotive. Its drama, size and power excite me. To my mind the elephant is the most benevolent animal that God ever created. It is just seventh heaven to sit for five hours or five days on a riverbank and watch them playing undisturbed it’s one of the sights you feel privileged to witness.”

Ahmed Feeding — Bob Kuhn

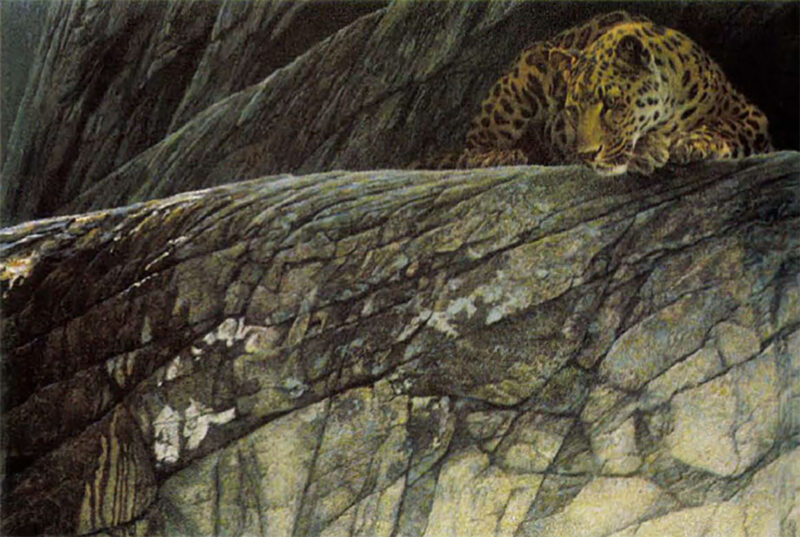

Canadian Bob Bateman, like Shepherd, is not a hunter, but he is drawn to the predators, because of their elegance and form.

“Lions have good strong shapes and infinite variety. Each lion’s face is different from another’s. They are recognizable, as people are, by the face — more so than most animals I know. In a painting I did of two lionesses, they were exact duplicates of each other except far their faces.”

Bateman has made six visits to different parts of Africa and is planning a seventh soon. “On each succeeding trip I had better luck in terms of seeing wildlife, getting close and getting good looks at them. But I’ve never spent a lot of time in one place-it was the usual hit-and-run.”

Like Shepherd, Bateman loves dry Africa-the sere landscape of dried grasses, rocks, stumps and water holes.” There is a kind of rawness to it, like Canada to a certain extent — it’s a bit Wyethy.”

Leopard — Robert Bateman

The allusion to Wyeth is not surprising, for Bateman acknowledges a strong debt to Wyeth’s stark realism, and one can feel it in Bateman’s own work and affinities. There is, of course, close attention to detail, a tendency to make seemingly small and insignificant things the real focal point of a painting, the subdued palette and the abstract use of space and contrast. Bateman will also approach a subject psychologically. In Wyeth’s case, this approach produces a feeling of isolation and anomie. In Bateman’s work, the effect is to make you wonder what the animal is thinking.

Guy Coheleach’s Africa is closer to Hemingway’s vision. His is the Africa of big game hunting, predation and man as an active predator in his own right. Coheleach feels he must have spent previous lives in Africa, so strong was his sense when he first arrived in 1967. “We got off the plane and were driving into Nairobi, and everything looked familiar to me, as if I should have been out in the fields looking at the foreigners in the bus, instead of the other way around. It was spooky.”

Whereas Shepherd considers elephants benign, Coheleach has had such bad experiences with elephants that in 1972, when he was “run over by an angry elephant, I decided to take out a gun license to protect myself in case it happened again. ” Coheleach does admit, however, that he provoked the elephant. He had been unable to sell an earlier painting of a charging elephant to a woman who was an experienced hunter of big game. “You don’t know what an angry elephant looks like, ” was her comment. Stung by her criticism, Coheleach had to admit she was probably right and resolved to correct this deficiency the next time he encountered an elephant. It was on the Zambezi River.

“The secret is to charge an elephant and call his bluff. Ninety-nine out of hundred times, he will back off. But no one told me this was the hundredth time, and this one didn’t do that. He chased me a hundred yards, knocked me into a ditch, hit me twice on the head with his tusks, wedged me into the bank with is foot, and started splashing me with his trunk.”

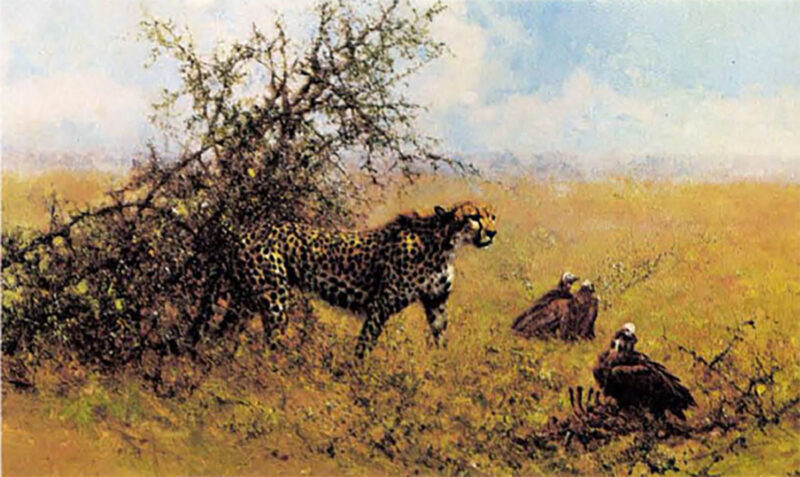

Scavengers — David Shepherd

Cohleleach’s guide came to his rescue, but thereafter, he has always gone armed into elephant country, and still paints angry elephants.

Coheleach enjoys the whole hunting experience, mostly because it is “absolutely hair-raising. I don’t think you can paint wild game without knowing a hell of a lot about hunting the hunted. If nothing else, it gives you that electricity and fear so that when you are painting that gazelle being chased by cheetah, there is something else you can add to it that the person who only sees zoo animals will never know. Whatever value I have as a painter, I’d be missing most of it if it weren’t for the hunting.”

Bob Kuhn was working as an illustrator for Field & Stream in 1956 when he got his first opportunity to visit Africa. “It was the only safari where I did a certain amount of hunting and it was hard to do everything. I painted a few little landscapes, made some little studies of dead animals, but I was taking my own stills, helping Warren Page make a film — I was a busy fella!” Kuhn has been back many times since then. “I felt it was absolutely necessary to study these animals in the wild, but I didn’t realize how different they were from zoo animals until I went over there and looked at them. There is no mistaking it. Wild animals are trimmer, the muscle tone is better. You can get a square, chunky lioness in captivity, but it’s not muscle, it’s flab — she’s just been lying around.”

Elephants and Sausage Tree — Guy Cohleach

Kuhn is especially fond of painting the Cape buffalo. “I like the shape, the solidness. In addition to their very business-like anatomy, I have a very sensual affection for the shapes of their horns — such a lyrical design that varies from animal to animal. Even the old timers that have worn the ends of their horns down, or broken them off. I guess I am attracted to the implied menace that is built into them — they never look cuddly. There are times when you feel you could go up to a sleeping lion and scratch his tummy, and he might roll over. You wouldn’t do that to a buffalo.”

Keith Joubert is fortunate to live in the bush close to his animal subjects. Born in Johannesburg, Joubert moved 350 miles north to the edge of Kruger National Park. While he lives primitively — no running water or electricity — he paints with Madison Avenue sophistication. He has an eye for graphic design, and boldly uses white spaces of canvas as compositional elements. Patterns and textures make up his landscapes, and details are offset by undefined spaces. The total effect is fresh, a balance of control and spontaneity.

Waterbuck – Keith Joubert

Joubert himself said, in an interview in Southwestern Art magazine. “You very rarely see an animal sticking out in a perfectly posed position with all the stripes and eyes and ears showing. Indicating just portions or parts of an animal gives an elusive feeling which is what Africa is all about. Africa is wild; it is not easily captured or seen.”

At the tum of the century, Kuhnert was struggling with the elusiveness of Africa himself. Shortly before his death, he wrote:

“The painter has the right to represent strange worlds. His eye does not recognize geographical borders. I have gone back again and again to my beloved land trying to soak in as much as possible, for its riches are virtually inexhaustible and life is sadly too short to be able to depict its fullness and beauty.”

Lion at Tsavo — Robert Bateman

When Kuhnert was painting, not many people had been to Africa. For most, the lions of Friese and Mayerheim were satisfactory. Today, we are well informed visually from television, magazines, books, movies, even slide shows of a friend’s photographic safari give us accurate impressions of Africa. So, while the artist’s audience is wider, it is also more sophisticated.

Contemporary artists have found that, even with the camera now serving as sketchpad, there is still no substitute for firsthand knowledge. Kuhnert has left us a rich legacy of unspoiled Africa, but he was still unaware of what Hemingway knew when he wrote, less than a decade after Kuhnert’s death in 1926, “A continent ages quickly once we come.”

Desert Brigands — Richard Friese

Africa is still wild, but her resources are not inexhaustible, although the romance of 19th century discovery dies hard. Peter Matthiessen’s words come back to haunt us-whole landscapes are alert, for change is taking place there at an accelerated rate. Painters will preserve the images of her wildness, but we can only hope that she will preserve her primitive heritage, and that these canvases will not someday become monuments to past glory.