Gertrude Legendre lived a life of adventure, hunting virtually around the world, hobnobbing with kings and celebrities, and then while serving her country, somehow surviving capture by the German Gestapo.

The guests at Medway Plantation had finished dinner and moved into the library, old Mrs. Legendre leaning on the arm of one of the men who served us, perhaps a butler, perhaps some other title. We were going to shoot wood ducks in the morning and had to get up very early, so most of the others went to bed, but Mrs. Legendre had spun tale after tale at the dinner table, recounting hunts in the Teton Range decades before it was discovered by Hollywood, safaris in East Africa before Hemingway, horseback treks through French Equatorial Africa, travels by pirogue through the Mekong delta of Indochina — known to young American men many years later by a different name — hunts in the mountains of what was then Persia, spartan camps in Kashmir, safaris in Abyssinia, a dozen other places, a dozen other adventures, and I wanted to hear more.

But as she was helped into her chair and I settled myself with a whisky, I had a sudden memory of drifting in and out of consciousness in an isolated hunting camp and waking once to find a silver-haired man standing over me and asking — I think I spoke — if he was the doctor.

“No,” he said, “I’m the angel of death and I’ve come to take you home.”

Well, that’s alright, I thought, he looks like a good man to go with.

I remembered, too, a tacky, dirty little room in a tacky, dirty little hotel in a decidedly unromantic arrondissement of Paris where I awoke alone after 36 hours of unconsciousness, and thought before I passed out again, Well, this is where I’ll die, just like Oscar Wilde.

Those two incidents flashed through my mind as Mrs. Legendre and I settled ourselves and I reflected that I was almost 50 years younger than she, and I had the advantage of vaccines and medicines and doctors that were nonexistent in the time and places she spoke of.

“Mrs. Legendre,” I said, “you make it all sound so carefree and exciting and fun, but surely there must have been some hardships, some bad times.”

“Oh yes,” she said …

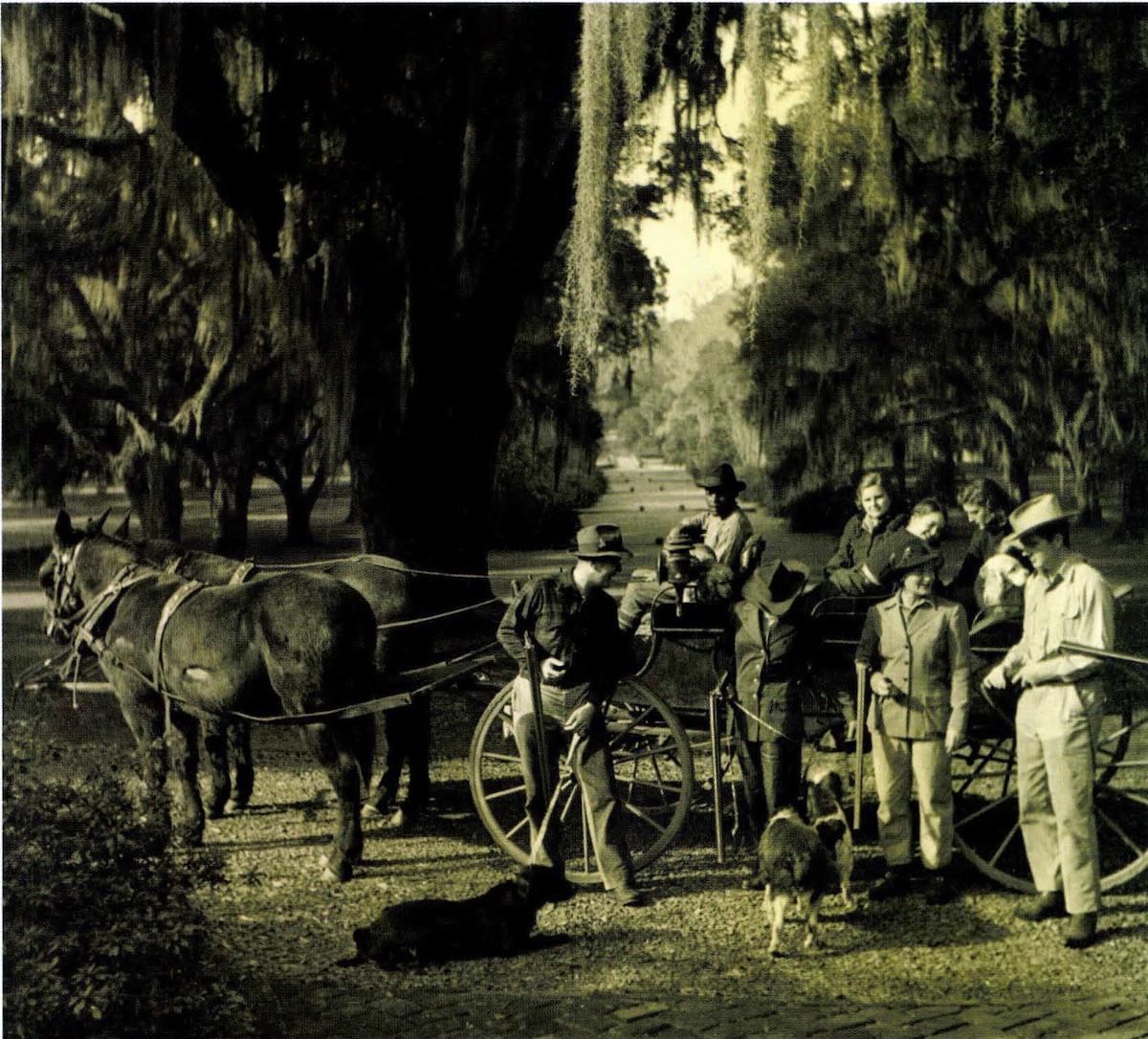

In the 1930s, Medway boasted one of the South’s most beautiful plantation manors. The 6,000-acre property is now protected by conservation easements granted to the Historic Charleston Foundation.

Her life spanned an arc from the horse and buggy to the space shuttle. She was born Gertrude Sanford in Aiken, South Carolina, in 1902, but time and place are meaningless. It is more accurate to say she was born into an aristocratic world of wealth so rarified and glamorous that she became the inspiration for the wealthy heiress played by Katherine Hepburn in Holiday. Her ancestors included Thomas Welles (1590-1660), the only man in Connecticut history to hold all four top offices: governor, deputy governor, treasurer and secretary. Her father and grandfather were New York congressmen as well as immensely successful businessmen, owners of the Bigelow-Sanford carpet company whose slogan was: “A title on the door deserves a Bigelow on the floor.” Her brother, Stephen “Laddie” Sanford, was an internationally famous polo player whose team won the U.S. Open five times.

Her family followed the pattern of their class and era, migrating with the seasons from their Beaux Arts mansion on East 72nd Street to their upstate horse-breeding farm to the milder climes of Aiken, interspersed with regular trips to France and England where her father kept stables of racehorses.

Their migrations always included a retinue of servants: butlers, chauffeurs, French governesses, cooks, most of whom — typically for that time — were considered family members in their own right. Eighty-five years later, Mrs. Legendre’s memories and stories of a cook, a horse trainer, a chauffeur, a butler, a beloved sewing-and-cleaning maid who chose to stay with the family rather than leave with her fired husband, were more vivid and real than her stories of her parents.

In Peter Shaffer’s Tony Award winning play Equus, the psychiatrist says: “A child is born into a world of phenomena all equal in their power to enslave. It sniffs, it sucks, it strokes its eyes over the whole uncomfortable range. Suddenly, one strikes. Why? Moments snap together like magnets, forging a chain of shackles. Why?”

Of all the sophisticated and accomplished people her parents exposed her to as a child, from Arthur Rubenstein to the then Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII, later still the Duke of Windsor), the one who most influenced her later life was a man named Paul J. Rainey.

The Sanford family and their staff head out for a morning of quail hunting at Medway Plantation (circa 7950). Photograph by Toni Frissell.

The immensely wealthy heir to a coal and coke-production fortune, Rainey was also a product of his class and era. His life revolved around hunting and horses and dogs, luxurious homes and private railroad cars, and polo. His was the first American polo team ever to beat the British, and the round brick stable he built still stands on the grounds of his once vast estate in northeastern Mississippi.

But Paul Rainey also had an adventurous side. He conducted expeditions to the Arctic to collect specimens (legend has it he roped a polar bear and brought it back alive for the Bronx Zoo, a feat I should have liked to witness through binoculars) and was one of the very first — possibly the first — men to film African animals while on safari.

In the summer of 1914, Mrs. Legendre’s parents hosted a party for Rainey where he screened a film of one of his lion hunts. Young Gertie had been sent to bed, but the excitement was too much for her.

“At nine, with sounds of the dinner ending downstairs, I was wide awake. I got out of bed, opened my bedroom door and scanned the hall. I darted to the head of the staircase and eased my way down along the banister. As I peered through the slats of the railing, I could just see through the half-open curtain of the living room archway. There it was: Africa in jumpy, badly lighted, black-and-white images against the far wall. I may have had a poor seat, but that evening changed my life. From that moment on, I knew I would go to Africa someday.”

However, before that chain of shackles could be completed, she had to grow up. She was educated at Foxcroft School in Middleburg, Virginia, then and now a prestigious boarding school for the well-heeled daughters of very affluent parents — the annual tuition is slightly more than the annual median American household income — the kind of school where girls take their own horses for fox hunting.

Most of Foxcroft’s graduates in 1920 spent the summer in a swirl of debutante balls intended to help them marry well and then retire. Gertie Sanford opted instead to go hunting with two family friends in the Grand Tetons back when Jackson Hole was, in her words, “a dusty frontier town consisting of a post office and couple of houses.”

Fox hunting and bird hunting were things she had grown up doing, but this was her first big-game hunt.

“Even the waiting was a thrill. There I was, sitting on a log beside a game trail on a ridge in the middle of the Wyoming mountains on a beautiful afternoon. I held the gun tightly, in a ready position, across my knees. The faint scent of gun oil mingled with the scent of the surrounding woods … ”

When I met Mrs. Legendre 80 years later, that first bull elk still hung in a place of honor in the log cabin she built at Medway Plantation to house some of her trophies.

Wyoming was followed by a succession of hunting and fishing trips to destinations that would be considered adventurous today — Alaska, Canada, the Laurentians, New Brunswick — and for game that are still considered challenging: Dall sheep, caribou, moose, brown bear. And all this was done at a time when Alaska’s largest city, “… in those days resembled a T.V. Western set — several bars and one hotel.”

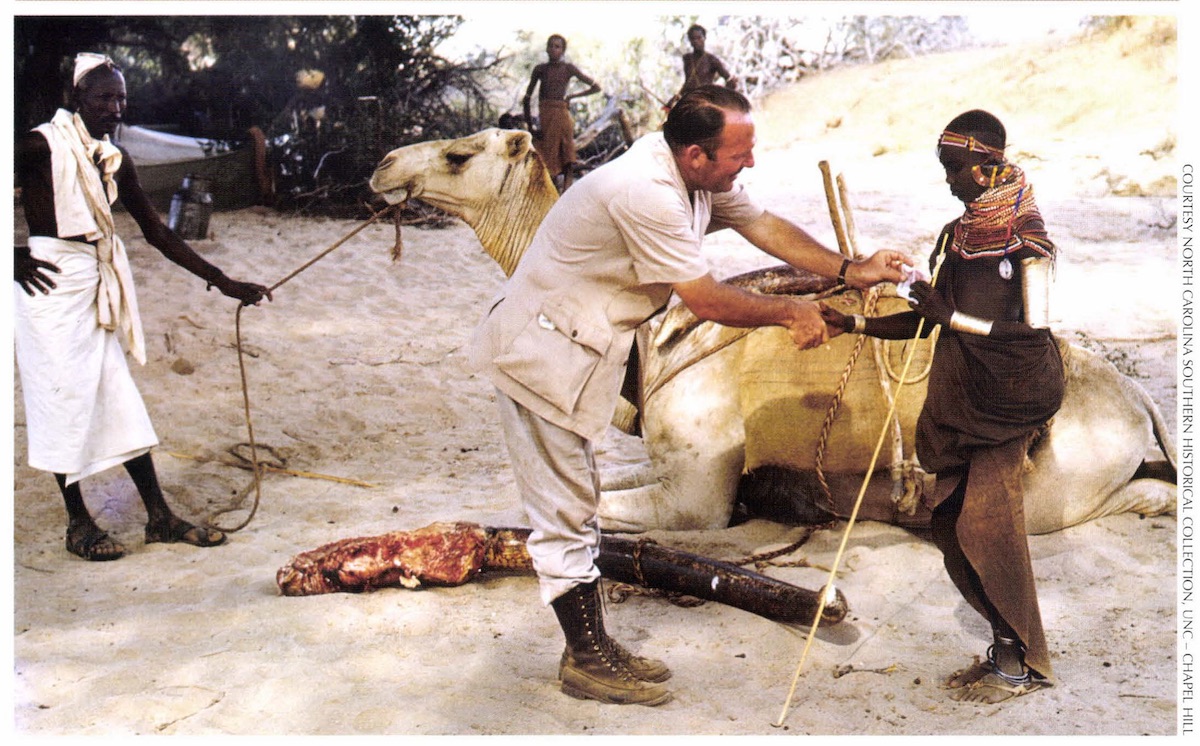

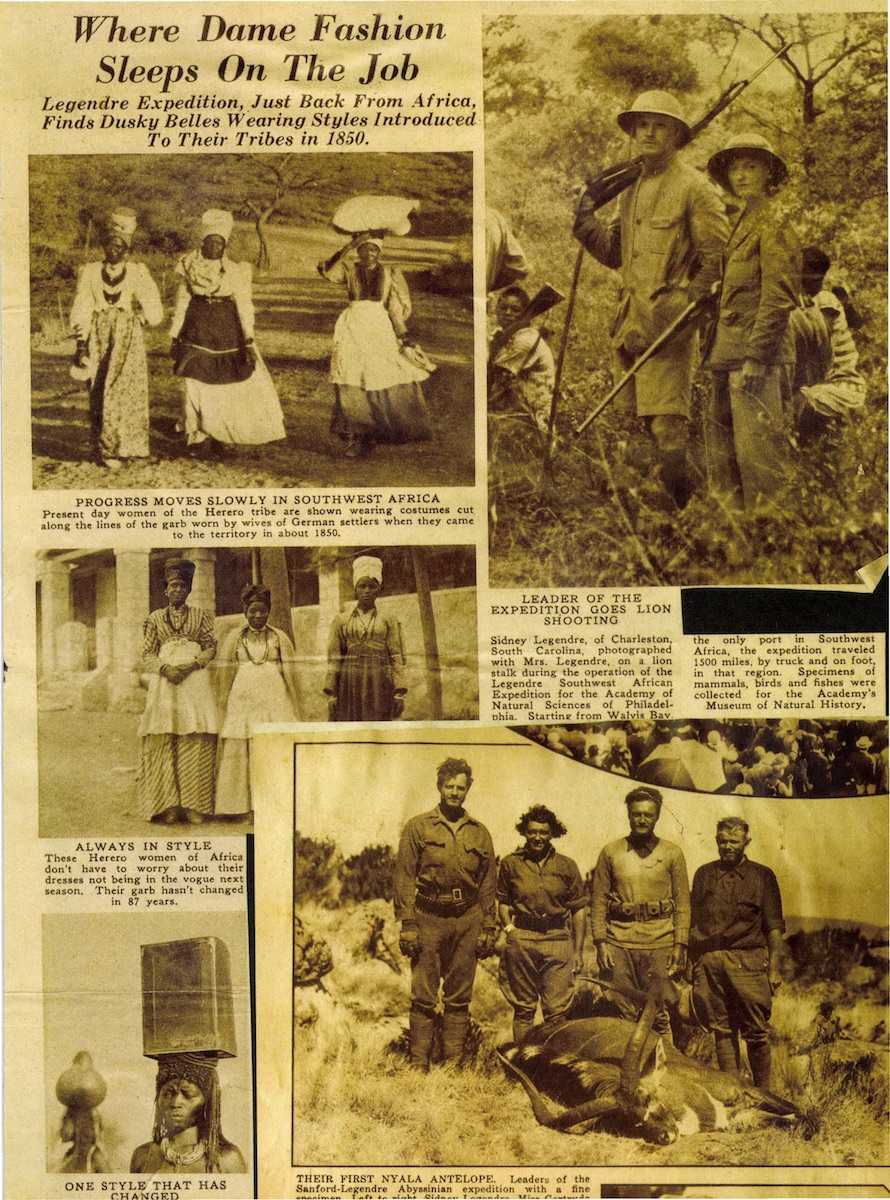

Gertrude’s hometown newspaper in Aiken, South Carolina, published photographs and accounts of her hunting expeditions in Abyssinia and Southwest Africa.

Thirteen years after watching movies while hidden on a staircase, Gertrude finally made it to Africa. Harold Talbott, president of the firm that produced more wartime airplanes during World War I than any other company, and later secretary of the Air Force, invited her and her brother to join him and his wife on safari.

Just getting to Mombasa involved 18 days of ocean travel for the perennially seasick Gertie, and with it came strange and conflicting advice for how to stay alive when they got to Africa. A hot bath every night would ward off germs. A hot bath every night would kill her. A strip of red flannel to keep the sun off her spinal column was the only thing that would keep her alive. If she went outside without a pith helmet, she’d be deader than a smelt in just a few hours. The only advice she followed was to take quinine, with her whiskey and soda.

The business of safaris was only just beginning, so everything had to be purchased on the spot in Nairobi: clothes, food, camping gear, medicine, even the vehicles that had no discernible springs and required constant tinkering and repair, tires going flat, radiators boiling over, making them happy if they could manage 40 miles in a day, a different campsite every night, folding chairs around the fire, toasts with whiskey and quinine, mosquitoes the size of moths beating against the netting, the grunting of lions, the eerie, mocking laugh of the hyenas, and always the plains full of game in unimaginable amounts, numbers so great it was impossible then to imagine it ever coming to an end.

“It was often a time for reflection — the kind of thoughtfulness that many people have never known. I still remember that feeling of remoteness from the world of cement walls and streets and city noises. I was miles away from the routine of social life — weddings, parties, polo, fancy clothes and repetitious, trite, silly talk I remember thinking I would like to stay forever in that open land with its strange night sounds and smells.”

She couldn’t however, and return to social life three months later introduced her to her future husband. Her father decided to rent an estate near London for the summer, a neo-classical confection known as Osterley Park, designed by Robert Adam and sometimes described as “the palace of palaces.” Among the many guests who drifted in and out were two brothers, Sidney and Morris Legendre, heirs to a sugar fortune in Louisiana. Gertrude Sanford was so smitten with them that when she went to the Riviera, she invited them both to join her.

The Riviera in 1928. The Great Depression was still two years away and the Roaring Twenties were in full swing, the height of the Jazz Age: Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald; Ernest Hemingway; Somerset Maugham; Harpo Marx; acerbic Alexander Woollcott and George Kaufman who would later write a play about him; suffragette poet and novelist Alice Duer Miller of The White Cliffs of Dover; author and professional hostess, “the hostess with the mostest,” Elsa Maxwell; Philip Barry, who would write Holiday about young Gertie and her family; wild stunts with motorboats by day; wild dances by night, the Charleston and the Black Bottom and the Lindy Hop, the very rich and the famous and the wannabees all playing as hard as they could, almost as if they knew the good times couldn’t last much longer.

Sixty years later, Gertrude Sanford Legendre would write: “The roaring Riviera. What’s all the fuss? Simpleminded nonsense and a lot of fun . . . ”

And also: “I honestly don’t remember anyone working that hard at writing except [Somerset] Maugham, and he was a complainer and not very likeable . .. Maybe it’s a mistake to meet authors. Being a good writer often has nothing to do with being a good person. In fact, the opposite is frequently the case. I don’t do somersaults at the mention of Hemingway or Fitzgerald; they were drunk most of the time.”

But while the band played on that summer, young Gertie danced with them all.

In the fall of 1928, she began making arrangements for another safari and invited both Legendre brothers to join. her. She had decided to collect specimens for the African Hall of the American Museum of Natural History, specifically mountain nyala.

According to James Mellon in his classic African Hunter, the mountain nyala had only been discovered 20 years earlier, in 1908, in south-central Ethiopia, known then as Abyssinia. Also according to James Mellon: “Sooner or later, every serious trophy hunter has to contend with the mule and the Abyssinian; both are visited upon us as plagues and the mule is the more agreeable of the two.”

Typically, Gertrude Sanford did it in style.

“We had to ship practically everything from the States to the port of Djibouti and hope that it would get there. I remember we spent hours in David Abercrombie’s store ordering special tents and flies to be made. We even got one of those invaluable portable toilets. It was the greatest invention of all; it made camp life almost civilized.”

Gertrude and Donald Carter (one of the curators of the Museum of Natural History) and the Legendre brothers met in Paris and started their trip from the Hotel Ritz. It took 17 days just to get to Djibouti and another three by train to get to Addis Ababa, the capitol, where there was only one hotel, and they were warned that if they went out at night, they should carry large sticks to ward off hyenas and wild dogs.

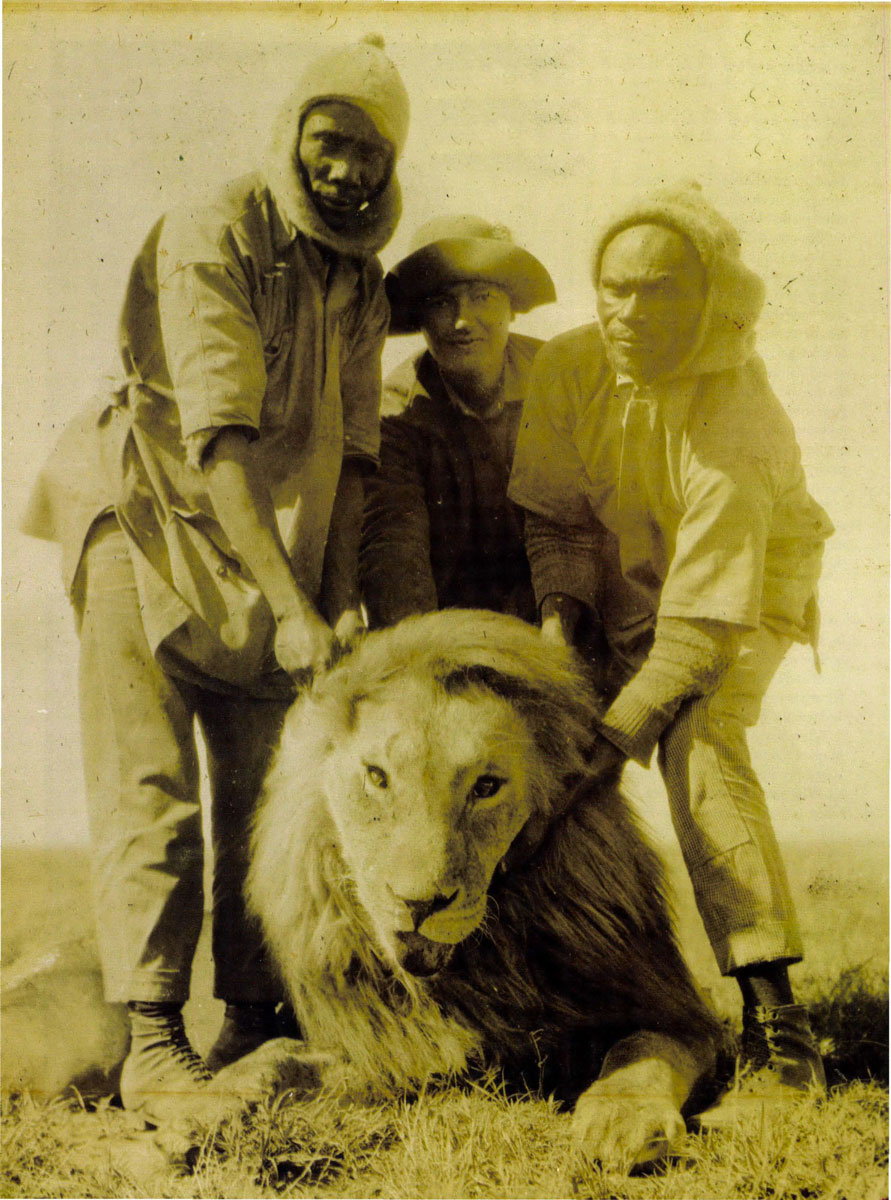

Gertrude Sanford (unmarried at the time) killed this heavy-maned lion in Kenya on her first African safari in 1928.

Also typical for Gertrude, they were invited to visit Emperor Haile Selassie, the Lion of Judah, King of Kings, Elect of God, direct descendent of both King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba. It took them 29 days to assemble the necessary gear and crew and mules, and they spent their evenings with the emperor in what she described as a study in contrasts.

The palace itself was a simple wood-frame building and the palace soldiers were all barefoot, but Haile Selassie sat on a golden throne and they ate 14-course meals off gold plates, while drinking tej, the national honey wine. Some evenings were spent watching formal entertainment; other evenings the emperor would play records on a Victrola and dance with the young lady who had already shot five lions in Tanganyika and who had come to do what only one or two men had yet done in his country. He must have been quite taken with Gertrude for he presented her with a riding mule from his own stable, along with a silver bit and a green velvet saddle.

James Mellon again: ‘Woe to the efrenji (wretched foreigner) who wishes to rent mules for a nyala hunt … ” Gertrude and the Legendre brothers finally assembled their 50 mules and muleteers, trackers, skinners and the gear and food they needed to survive for four months, and on the day of departure she and the others spent an entire morning carefully weighing and balancing the loads on their mule train. The lead mule promptly started bucking and, “… threw off his entire load and the rest did the same. It was chaos. Equipment was everywhere. I’ve always said the easiest hunting is on elephants. You can have the mules!”

But the mules were only the beginning.

“The whole trip was a tough one — heat, rock cliffs the mules couldn’t climb, thorn trees, lava slopes, flies, mosquitoes, anything else you can imagine.”

The muleteers came from different tribes and fought among each other. One night they got drunk and got girls from a nearby village into their tents and raised such hell the Legendre brothers had to drive them all away. Smallpox broke out in the camp and the tents and blankets had to be burned. Then malaria broke out. The muleteers got drunk again, and when Morris Legendre fired the headman, the whole group quit. The cook mistook fly repellent for cooking oil. Still, they hunted constantly.

“Finally, we had to turn back. Our plan had been to cross the Omo River and follow the White Nile, but the river was too high to ford and the mules would not swim it. The rains had come early and chicka mud was so thick that the mules couldn’t get a foothold. We had to lay down our tent flies for the animals to walk over. Everything was soaked through and never dried out. It finally got so bad that after a day’s progress, we could look back and see where we’d camped the night before.”

But the safari ended with more than 300 mammalian specimens, from rodents to a 40-inch nyala bull, more than a hundred birds, and with Gertrude Sanford engaged to be married to Sidney Legendre.

In today’s Great Recession, the truly rich have been largely unaffected. The same was true during the Great Depression. The moderately affluent, the middle class, and especially the working poor, were wiped out, but families with names like Vanderbilt, Biddle, Duke, Rockefeller, Pratt, Mellon, Sanford and Legendre were unaffected.

Gertrude Sanford and Sidney Legendre were married on September 17, 1929 and Black Tuesday (October 29) came and went without making a ripple in the newlyweds’ lives. Part of that was because their honeymoon was a pack-trip through the Cassiar Mountains of British Columbia, where they stalked sheep and goats through snowdrifts and were tent-bound for days in a blizzard. Her description of it was simply: “It was glorious.”

Sidney and Gertrude Legendre in 1929 with Clippy, their cocker spaniel. After Sidney died, Gertrude wrote: “I shall always be married to a young and vital man who sees only the youth in me.”

When they returned, the first thing they did was buy Medway Plantation, the oldest masonry structure in South Carolina. Today, it’s a beautiful and unusual pink Dutch-stepped-gable gem whose ivy-covered walls lean in toward each other as if each was politely trying to hear what the other had to say, and whose 6,695 acres are protected by conservation easements and environmental trusts, courtesy of Gertrude Legendre.

When the young couple bought it, however, it was a dilapidated historic building with no electricity, no running water, no plumbing, no heating. Only a couple whose dream honeymoon was hunting in the snow could have fallen in love with the ancient wreck.

From 1932 to the outbreak of the war, Gertrude and Sidney Legendre Ied three more expeditions for various museums, each of which lasted almost a year, what with planning, travel, procuring permits and supplies, and hunting.

In Indochina they hunted their way alternately by pirogue and elephant and horseback, in places with a French army escort against bandits. She was the first white woman the “Meo” tribesmen (Hmong) had ever seen, and they were confused by her wearing men’s clothing, the men bowing, the women reaching out to touch her. In Laos they visited the king in his stucco palace overlooking the Mekong River. In the northern mountains she shot the only tiger they took, a nine-foot, 600-pound male.

In Southwest Africa, later Namibia, they hunted across the Kalahari to the Okavango. Waiting and waiting and waiting for supplies in Windhoek, a local official berated Sidney for taking his wife on such a dangerous expedition.

“I’m not taking her; she is taking me,” he replied.

They suffered through clouds of flies, blistering heat so severe they could only hunt until nine in the morning, constant thirst, bad water and bad tempers among their drivers. One, an Afrikaner almost seven feet tall and 300 pounds, was capable of singlehandedly lifting a truck out of “ant bear” (aardvark) holes. They took everything except kudu, which eluded them time after time until finally, after three months of hunting, they had to give up and hunt their way back. Five miles from the downtown Windhoek, they found a bull in a ravine.

Bureaucratic red tape and flies in the Kalahari, more red tape and bandits on the Mekong River, and in Persia, only recently renamed Iran, even more red tape and secret police.

“They were so obvious and clumsy that one day I motioned to them to get into our droshky (a horse-drawn Victoria) and show us through the market to buy pustines” (sheepskin-lined leather coats). To my surprise, they climbed in and rode around with us all afternoon speaking good English. They were very cooperative for secret police.”

They needed permits for everything, and even after they paid, the permits still didn’t arrive.

“Tomorrow.”

“A month from tomorrow.”

For obscure reasons, the Minister of Education was in charge of the permits, and after 22 days of waiting, he called them into his office where he announced they wouldn’t be allowed into the country with so many guns. “Over five hundred,” he told them solemnly. Someone had mistaken the listed calibers and gauges for the number of guns being brought.

The Shah’s hotels were riddled with fleas, and the toilets consisted of a hole in the floor with two-foot supports, but the Shah wanted to impress them, so they were allowed to consume trout and caviar, partridges and Russian vodka, and to buy gold and pearls, rubies and emeralds in the markets, but “… the people seemed anxious, maybe even frightened. Most were very poor and seemed unhappy. They clung to their pustines, their only possession. Summer, winter, spring; they never let them out of their sight.”

Finally, accompanied by their secret police escorts, they drove north into the mountains, past mud-walled cities and ornate mosques with onyx and alabaster floors. The bureaucratic delays had put them into the rainy season and they hunted in continuous mud, but managed to get everything they wanted. They had their trophies and specimens, but the secret police wouldn’t let them leave without examining every item, developing (and damaging) all the film, and demanding egregious “export fees.”

WorId War Two. The Greatest Generation. Like practically everyone else in America, the Legendres immediately dropped everything and volunteered. Sidney joined the Navy and was shipped off to the Pacific. Gertrude used her connections to wrangle a job for herself in Washington at the precursor to the Office of Strategic Services which was itself the precursor to the CIA. Government in those days, especially any part of government that had anything to do with intelligence, was very much an Old Boys Club. OSS was commanded by Colonel (later General) William “Wild Bill” Donovan , who may have been the first generation son of Irish immigrants, but he was a football hero graduate of Columbia University, a decorated World War One hero, a lawyer, a U.S. Attorney, and most importantly, a trusted advisor and friend of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

When Wild Bill Donovan tapped David Bruce, who was very much an Old Boy, to head OSS in London, Gertrude was one of six women chosen to work there. She stayed there, enduring the Blitz, until the September following D-day when she was sent to recently liberated Paris to help OSS set up shop locally.

Much of what OSS did during the war is still, to my knowledge, classified, so much of what Gertrude Legendre later said and wrote about her motives for going to the front, specifically to “Wallendorf where German prisoners were being interrogated, should be taken with a block of salt.

“A crazy lark.”

“A wild adventure with some old friends I just happened to run into.”

“Something to do during a five-day leave.”

Right. One of the old friends was a Naval Lieutenant Commander, the other an Army Major. She did indeed love adventure, and she undoubtedly had tremendous courage, but she wasn’t stupid.

Whatever the reasons, four days later (excuse me, what was that again about a five-day leave?) she and the soldiers she was traveling with came under sniper fire only a few kilometers from Wallendorf. Two of the three soldiers were wounded, and as they lay together in a mixture of blood, mud and motor oil, waiting to be captured, they all quickly burned their OSS identity cards and concocted cover stories. (Excuse me, what was that again about “old friends she just happened to run into?”) And Gertrude Legendre became the first American woman taken as a prisoner of war on the Western Front.

(After the war, Wild Bill Donovan maintained the story that it was all a wild and irresponsible lark, but that too should be washed down with salt.)

What is unquestionable is that if the Germans had suspected she was with OSS, her fate would have been horrifying. As it was, they seem to have bought her story that she was a Red Cross volunteer who was working temporarily as an interpreter for the two officers. In fact, they seemed confused as to precisely what to do with her. Initially, she was interrogated by the regular German Army officers and kept in an ever- changing sequence of conditions, improvised jails in private homes, vast prison camps little better than concentration camps, an old barn, a barracks, a spectacular 13th century castle in Diez.

Then she was turned over to the Gestapo and taken to their headquarters in Berlin.

Torture was a specialty of the Gestapo, as were murder orders that were issued with the victim’s name space left blank, to be filled in at someone’s whim, but she was transferred almost immediately to a criminal prison in Wannsee and kept under 24-hour guard. She was repeatedly interrogated, but confusion reigned supreme in the German army toward the end of the war, and no one seemed to know what to do with her or what to make of her. Once she was asked outright what the letters OSS stood for and got away with playing the bubble -headed society girl.

Torture was a specialty of the Gestapo, as were murder orders that were issued with the victim’s name space left blank, to be filled in at someone’s whim, but she was transferred almost immediately to a criminal prison in Wannsee and kept under 24-hour guard. She was repeatedly interrogated, but confusion reigned supreme in the German army toward the end of the war, and no one seemed to know what to do with her or what to make of her. Once she was asked outright what the letters OSS stood for and got away with playing the bubble -headed society girl.

“Oh, heavens, I don ‘t know. I suppose it’s some sort of officers’ social club.”

Finally she was moved to the Rheinhotel Dreesen in Bad Godesberg, on the banks of the Rhine, where Hitler used to go to relax. Her fellow prisoners included French generals, colonels, diplomats, the Prince of Montenegro, and Charles de Gaulle’s sister, and for two months her situation improved dramatically.

When the American Army began to close in on the Rhine, the prisoners were all moved across the river to the Hotel Petersberg in Königswinter, another luxury hotel where Hitler once made a fool of Neville Chamberlain. When the American army reached the banks of the Rhine, Gertrude and the other “special” prisoners opened all the windows just so they could hear the sound of American tanks.

The next day they were force-marched east and herded onto a train, but just before it took off, two civilians ordered her off and drove her to a private house in Kronberg. For several weeks she lived in comparative luxury with a well-to-do family, the idyll marred only by continuous Allied bombing raids.

The circumstances of her escape are as mysterious as her “jaunt” to the front.

She was told orders had been issued in Berlin for her to be turned over to the Swiss. SS officers drove her south, but at the border, customs officials had no such orders and refused to let her cross. The SS took her to a safe house until night, and told her she could get across the border by train, that she was to stay on the train until it got to Singen, that her story to the Swiss authorities was to be that she had been helped by French farmers, and that she was never to mention any kind of German assistance.

She walked by herself through the darkened streets to the train station. At the far end of the platform a tall man in a trench coat was watching her. When the train arrived, she slipped on board in the dark and confusion of descending passengers and hid under a seat. An official began to make his way from compartment to compartment, checking the seats with a lantern, so she slipped out and locked herself in the toilet. The train finally started and she once again hid herself under the seats.

Then the train stopped. She could see the white gates of the border crossing, but the train had stopped short of it. She climbed out of the train onto the tracks and walked slowly, staying in the shadows of empty freight cars. When she got to the last car, only 50 yards or so from freedom and safety, she suddenly sensed someone behind her. It was the man in the trench coat.

“Run,” he said.

She ran. She heard whistles, someone shouting at her to halt, threatening to shoot, footsteps chasing her, the Swiss border guard ahead of her shouting at her to stop.

“American,” she screamed. “American passport,” and she ran under the barrier.

“I have no idea why the German guards didn’t shoot me,” she said later. “Perhaps something had been arranged. I never found out.”

In 1946 Gertrude was already planning her next expedition, this time to the Indian state of Assam for the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale. To paraphrase Tolstoy: All successful expeditions are alike; each unsuccessful expedition is unsuccessful in its own way.

Assam is in the remote northeastern comer of India, and in 1946 you couldn’t get there from anywhere. The good news was that a tea plantation had been converted to a vast military base during the war, where B-24 bombers flew over the eastern end of the Himalayas, dryly referred to by pilots as “the Hump.”

The base and all its provisions, seven square miles worth of supplies where tigers roamed at night, had been abandoned, so gearing up was relatively easy. Unfortunately, their porters, trackers, skinners and bearers simply refused to go into certain prime hunting areas because they were inhabited by headhunters. One of their head guides ran out of opium and refused to go anywhere until his quota arrived.

One species, the takin (a member of the sheep family that looks like a cross between a yak with mange and a wildebeest), had to be abandoned altogether because the porters refused to make a 10,000-foot climb so close to the Tibet-Burmese border. The portion of jungle they could hunt was completely void of game. Crossing a river, their riding elephant (named Alfred) and the opium-smoking guide were both washed away and had to be rescued.

Their best chance for a tiger came as they were crossing a river on bamboo rafts and an enormous tiger came out to drink less than 50 yards from Gertrude. Her rifles and camera were all packed away.

The highlight of the trip home was visiting the Maharaja of Cooch-Behar where Gertrude did shoot a leopard, but without any pride in the accomplishment because it was a driven hunt.

Back at Medway, with neither warning nor fanfare, Sidney’s heart gave out. Forty years later Gertrude wrote:

“Every evening, I sit at one end of the dining room table facing his portrait. He stands there in his shooting jacket with a gun over his shoulder, looking cool and detached at the portrait behind me — that of a young, confident woman looking less like me than I remember. Sidney is exactly as he was. I have no memory of his aging. In my mind, I shall always be married to a young and vital man who sees only the youth in me.”

She continued to hunt, of course: Nepal, for the Peabody Museum again, where she visited the Maharaja of Nepal and took some fine specimens; Chad; French Equatorial Africa; Rey Bouba, now part of Cameroon, but then an independent sultanate where she was entertained by the Sultan; Gabon, where she stayed with Albert Schweitzer.

Bing Crosby hunted bobwhites at Medway in 1965. With the famous actor/singer are two plantation staffers, identified in the old photograph only as “Ray and Junior

Gertrude even married again, briefly, but Medway and memories began slowly to become more important to her. And age slows us all down. Forty years later her writing and conversation were always of the time when Sidney was alive, the hunts with Sidney, the adventures with Sidney, the good times with Sidney.

“Mrs. Legendre,” I said, “you make it all sound so carefree and exciting and fun, but surely there must have been some hardships, some bad times.”

“Oh yes,” she said. She waved one hand casually, as if waving away a mosquito, or a memory.

“Oh yes, there were some hardships, some bad times, but I don’t remember any of that.”

Note: Gertrude Legendre passed away in 2000, the year after I met her, at the age of 97. In addition to two autobiographies, she left one of the greatest architectural gems in America, now protected by conservation easements granted to the Historic Charleston Foundation, and 6,000 acres of forest and wetlands protected by conservation easements granted to the Ducks Unlimited Foundation. Her epitaph might well be her own assessment of herself: “I don’t contemplate life; I live it.”

All photographs courtesy Special Collections, Addlestone Library, College of Charleston, SC.