Years ago, sweating, prone, almost out of time and watching mirage slow to a crawl through the 20x Redfield, I shaded downwind just out of the X-ring and caught it. “Good call,” came a voice behind the line. I rolled over, slid the bolt open on the Remington and nodded my thanks to the range officer. He sat easily on the stool, of medium build, solid but not fat, with chestnut hair and chocolate, ever-smiling eyes. He ran the line with a chuckle that belied his smooth efficiency. A shooter of long experience. “You shoot a 37, too,” he beamed.

So I recall my first chat with Alvin Biesen.

Remington sold only 3,820 Model 37s between 1936 and 1942 when war-time production edged out this fine .22 target rifle. It would be replaced by the Model 40x in 1955.

Al clearly liked to see good scores shot with this uncommon rifle. “Mine’s at the shop,” he said. “Stop in for a visit. Sinto Street.”

The narrow stair from the garage hooked right into the basement shop. Biesen worked his magic on a bench just inside the door, on the left, under racks of hand tools. Thumbtacks papered cupboards and remaining wall space with notes and hunting photos and bullseyes chewed hollow by bullets. A picket of stiff, slender old Parker shotguns stared from a dusty cabinet on the right. “I like the Parker,” he told me.

The narrow stair from the garage hooked right into the basement shop. Biesen worked his magic on a bench just inside the door, on the left, under racks of hand tools. Thumbtacks papered cupboards and remaining wall space with notes and hunting photos and bullseyes chewed hollow by bullets. A picket of stiff, slender old Parker shotguns stared from a dusty cabinet on the right. “I like the Parker,” he told me.

I bent to clear joists on the tortuous path through crunching wood chips, past the punch press to a mausoleum of aging walnut. A bulb lit the crowded shelves dimly. “I’m saving this one,” he said, pulling out a dense feather-and-fiddle blank, burnt honey and black. He had X-ray eyes for fine walnut.

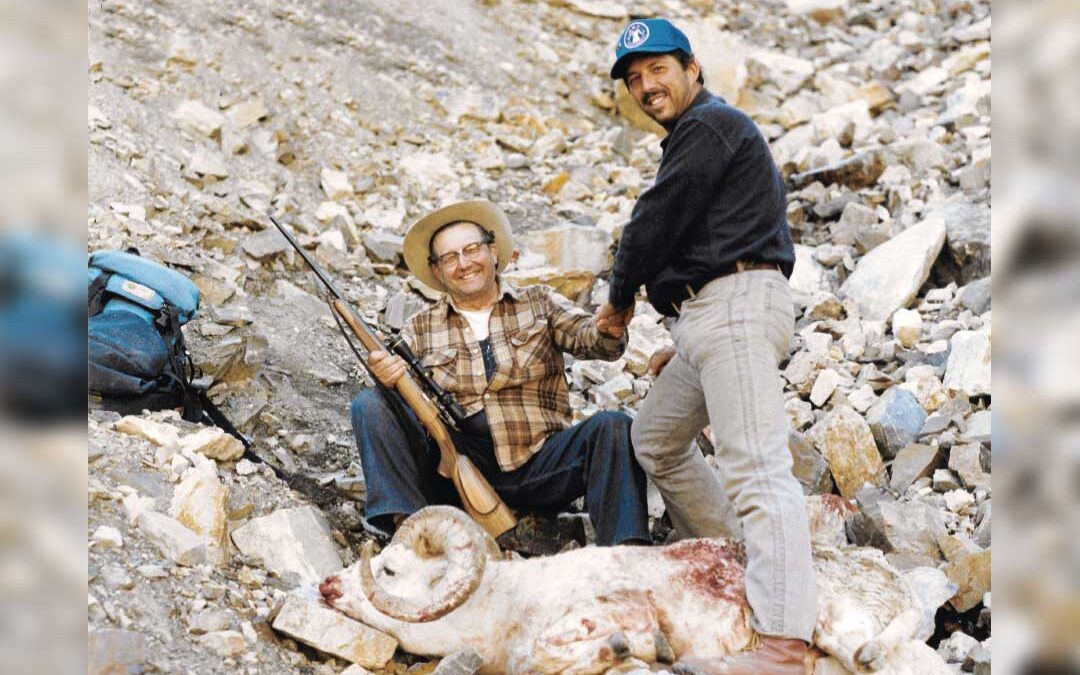

Beyond his affinity for the 37 and figured wood and hunting rifles with Depression-era profiles, I’d find in many visits to his basement that Al Biesen had a passion for people. Given an audience, he’d spin yarns without pause—or, it seemed, a glance to his rasp as rivers of chips cascaded from a $1,000 blank. These weren’t tales of his hunting prowess or of records-book game, but instead anecdotes woven into biographies, of customers and companions, of characters whose misdeeds endured forever as fodder for Biesen’s repertoire.

He gave due respect to Shelhammer, Linden, Brownell and other great stockmakers who had preceded him or worked as contemporaries. The “classic” bolt-action hunting rifle was birthed on their benches, and from the pre-war masters at Griffin & Howe.

“But,” he would remind me, “Not many gunmakers can say they’ve raised six children on what they’ve earned building rifles.” He was proud he had—proud, too, that he wasn’t “just a stocker.” He did most of the metal work on his rifles. The rifles that impressed O’Connor.

The frost was heavy that morning on the North Kaibab in 1937. Riding along the rim of a broad draw, they spied a buck about 200 yards away:

“I slid off my horse, planted my posterior solidly on the ground, and shot the instant the top of the post in the old Noske 4x scope came to rest…. The buck went over stiff as a paper deer….”

Kills like that, and his wife’s Mozambique score of 17 animals with 19 shots endeared the 7×57 cartridge to Jack O’Connor. By the mid-1950s, he was pining for another rifle so chambered and asked if Winchester could supply a Model 70. “They said they had exactly one 7mm barrel left and that they’d cook one up for me.” He sent it to Al Biesen, who “turned the barrel down to lighten it, chopped it off to 22 inches, fitted a fine stock of French walnut and a Weaver K4 scope….” An auto accident early in 1957 left O’Connor hospitalized. He surmised his recovery began the day Biesen brought him the finished rifle.

Outdoor Life’s celebrated shooting columnist became aware of the young Wisconsin stock-maker about the time he shot the big Kaibab buck, about the time his gun writing first saw print, “in 1937, as I recall,” Al Biesen told me. “The year Winchester came out with the Model 70. I needed to get noticed, so I offered to make a rifle for Jack. He sent me a Titus barrel and a Springfield action. I put them together and made a stock.”

Al Biesen started making rifles for O’Connor in the late 1930s.

O’Connor didn’t like the rifle. Biesen swallowed his pride and started over “with a Mauser and an ’06 barrel. Jack paid for that job.” It was the first of many, and a relationship that lasted until O’Connor’s death on a cruise in January, 1978. “He made me the most famous gunmaker in the world! I gave him a 25 percent discount.”

Other legendary gunmakers—Adolph Minar, Alvin Linden, Bill Sukalle, Lenard Brownell, Tom Burgess, Earl Milliron, Fred Wells, Clayton Nelson—built rifles for O’Connor; but Biesen had the inside track for stock work. “My wife and I,” wrote Jack, “now have three .30-’06 rifles…. My pet of pets, not only because it shoots well but because it is a very lucky rifle, is one I had put together about 1947. It has a 22-inch Sukalle barrel with a 1:12 twist, a Lyman 48 and a ramp front sight. In addition it is fitted with a Lyman 2 1/2x Alaskan scope on a Griffin & Howe mount. Al Biesen stocked it for me with a fine piece of Wisconsin black walnut.”

As O’Connor admired Al’s eye for line and balance, his inletting, detailing and checkering skills, he respected the gunmaker’s knowledge of stock wood. “French walnut is the preferred material for fine rifle stocks made by such crack American stock makers as the late Alvin Linden and Bob Own, and by Alvin Biesen, Griffin & Howe, Leonard Mews and other fine stockers who are still practicing their art.”

Jack noted: “The late Alvin Linden, one of the best stockers that [sic] ever ever practiced the trade, did not care for myrtle and said he had seen few blanks that ever stopped warping. Alvin Biesen says he finds it is too brittle. On the other hand, myrtle is the favorite wood of many stockers….”

When a single reference served, O’Connor named the man in the Sinto Street basement: “[Maple] is a strong, hard, close-grained wood that takes checkering well. Alvin Biesen says that he finds it more stable than walnut, showing less tendency to warp.”

My visit to the shop brought the great gunmaker nary an order. He seemed OK with that. Mostly I came to listen, and he was certainly OK with that—though often other men with deeper pockets afforded an audience thick enough to clog the aisle between vise and Parkers.

Al was hard to interrupt. His stories were entertaining, and he artfully avoided pauses. Only Genevieve’s faint dinner announcement from the kitchen above would truncate a tale. She wouldn’t repeat the call, and evidently was loath to wait, for Al would summarily strip off his apron and shoo us off with a smile that didn’t need words.

Twenty-three years ago, when his memory was beginning to fade, I feared his own story would be lost. We had both come from the Midwest—he from Wisconsin, I from Michigan. It seemed a fitting preface to my question: How’d you get here?

He was born in La Crosse, March 3, 1918, months before the armistice in Le Francport that ended the Great War. “As a lad, I worked in a blacksmith shop, where I had to furnish some of the coal. It cost $3.25 a ton, so I gleaned coal from a Milwaukee roundhouse. I learned to shrink steel wheels on wood-spoke rims and once shoed a team of Clydesdales in 28 minutes.” The Depression challenged his resolve, but he proudly told me he hadn’t lost a day’s work since 1936, “…when I had a WPA job that paid 50 cents an hour.”

Like most boys then, he found time to hunt. “In 1933 or ’34, the last year it was legal to use live decoys, we tethered mallard hens on the water, then pinched captive drakes to get them to talk. In 1938, a year after Genevieve and I married, I bought a DCM Springfield for $5 to hunt deer. Eight of us young men threw in to buy 40 logged acres for hunting. Bag limits had much to do with opportunity. I once shot five deer fast with a Remington 81 in .35. Another time with a 30-40 Krag and 180-grain Bronze Points I tumbled three on the run. After a Dakota pheasant hunt we draped 150 roosters on our ’34 Plymouth.”

Al worked for Autolite during World War II. He sensed opportunity in the shop’s tooling and “…ordered 20,000 8mm bullets from Vernon Speer. I figured I’d earn enough to pay for them before they arrived, but they came right away! In those days, though, people gave you the slack you needed. Vernon was a gem. I hustled 13 bushels of surplus cases and 300 pounds of 4895 powder, then used Autolite’s tooling to form and load the ammunition. You never know what you can do until you try!”

The Biesens moved into their basement on Spokane’s Sinto Street before Al could put a house on it. Later, he sold half the residential lot “to tool up” the shop.

“I came to the city in ’48,” he said. “Bought a house for $8,000, peddled it for $10,000, bought it back for $6,000. Then I moved it to where it is now. Genevieve and I raised four boys and two girls: Don, Carl, Roger, Joyce, Eunice and Christopher. Roger came to work with me.”

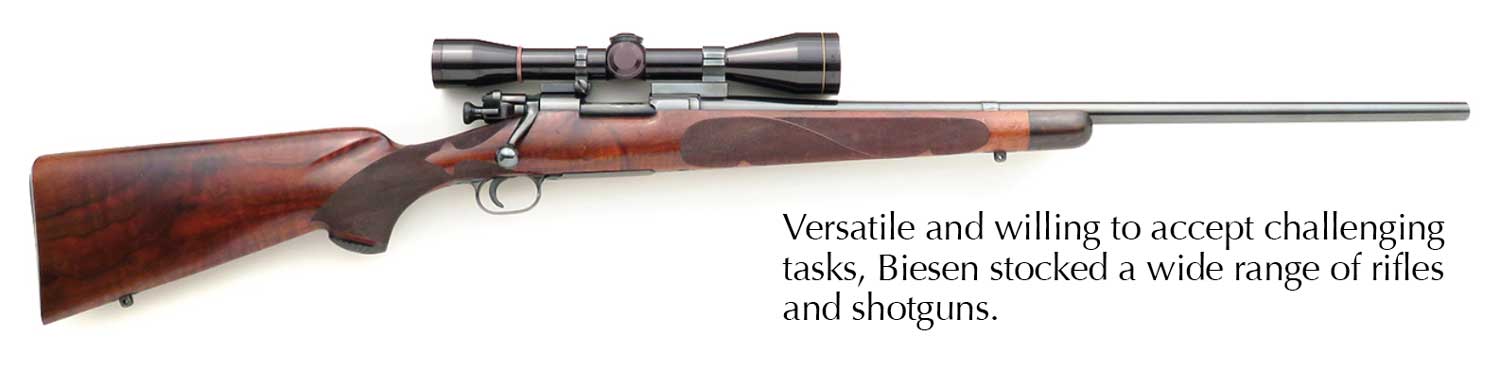

Al Biesen had an eye for what a hunting rifle should look like, what made it feel natural in hand and effective in the field. When clients picked up a Biesen rifle, they wanted one like it.

“I have a favorite and very elegant .270 stocked in French walnut,” wrote Jack. “It is a Model 70 Winchester extensively remodeled by Al Biesen….” That was probably the first of the storied pair of .270 mountain rifles he fashioned for the gun writer. Later called “Number 1,” it was built on a 1953 action. Biesen turned down the 24-inch barrel and cut it to 22 (Winchester hadn’t yet introduced a Featherweight version of the Model 70). The 4x Stith Kollmorgen in Tilden mounts was no doubt Jack’s choice. On a 1954 Wyoming hunt, that rifle accounted for a fine elk. Later it killed a Dall’s ram in the Yukon and went with the O’Connors to Africa and India.

This late-model, limited-run, Biesen-pattern 70 Featherweight is Winchester’s tribute to O’Connor.

Two years after recovering from his ’57 auto accident, O’Connor bought a Featherweight Model 70 in .270 from Erb Hardware in Lewiston. He gave it to Al: “Make it like the first.” With a 4x Leupold Mountaineer in Buehler mounts, Jack’s “Number 2” shot even better. Soon O’Connor was using it almost exclusively, from Africa to Iran, the British Isles to British Columbia. His last three Stone’s sheep would fall to that rifle.

Biesen supplied O’Connor with other rifles on Winchester 70 actions, including a .375 in 1960. Fellow sheep hunter Prince Abdorezza Pahlavi supplied the walnut from his native Iran. Biesen followed that rifle two years later with a .338. After using the then-new Remington 700 in 7mm Magnum on a 1962 safari, O’Connor instructed Biesen to put a 24-inch 7mm Magnum Buhmiller barrel on a Model 70 action, restock the rifle and add a 4x Leupold scope in Redfield mounts. In Idaho’s Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness in 1964, this rifle would take the biggest elk of Jack’s career.

O’Connor also appreciated Mausers. “Curious to see what could be done with a gilt-edged .244, I had Al Biesen build me, on a short Model 98 type Mexican Mauser action, a .244 with a light 24-inch barrel and a 1:10, instead of the standard 1:12 [rifling] twist. With the Leupold 8x Mountaineer scope on a Redfield two-piece mount, it weighs eight pounds…. Much to my disappointment, though, accuracy was very poor. The chamber has a long throat…. I was about to send the rifle back to Biesen to see what he could make of it when I decided to see what it would do with Speer 90-grain bullets in front of 48 grains of No. 4831. Accuracy was sensational.”

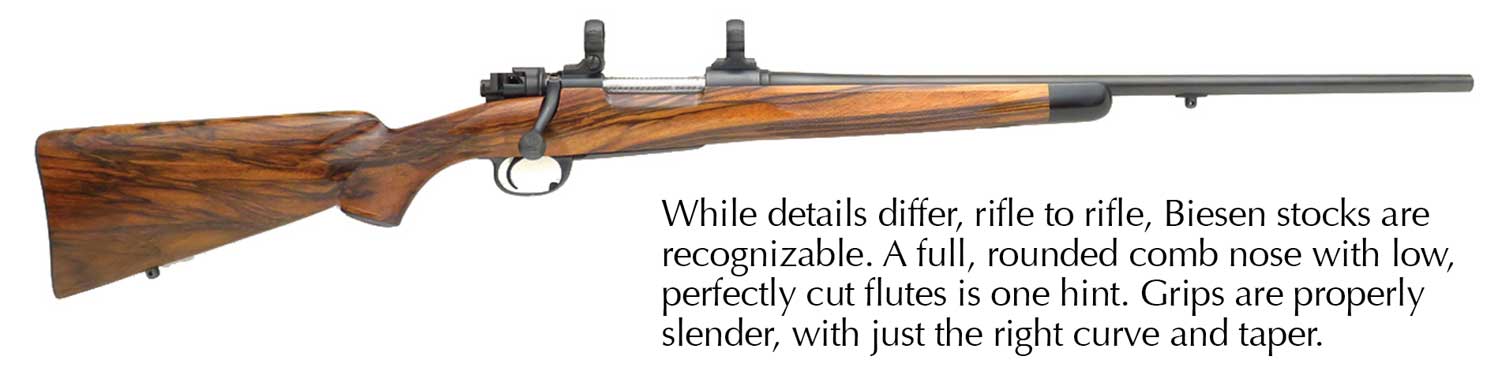

Known for his rifles on Winchester 70 actions, Biesen used others too, including Mausers.

That was in 1958. Eight years later, Al built for O’Connor a .458 on a Mark X Mauser. Celebrated for his “mountain rifles,” Biesen was hardly limited to that form. “Since WW II,” declared O’Connor, “a good many .416 rifles have been built by such custom gunsmiths as Griffin & Howe, Al Biesen and Tom Burgess.” Jack retired from Outdoor Life in 1972. A .280 on a Ruger 77 action wasn’t yet finished when he passed away. At his family’s request, Biesen completed the project.

Model 70s and various Mausers appealed to other clients, too. While Al said he preferred Douglas barrels, he let the customers choose. But once main parts were supplied, Biesen wanted a free hand. You could tell him which fittings you wanted, and suggest stock layout. But if he decided that a rifle fashioned to your whims didn’t properly showcase his ideas or work, he’d tell you. He had the ability and resources to deliver what you didn’t have the sense to order. Wrote O’Connor: “… for rifles of light and medium recoil the best [buttplate] material is steel, checkered so that the butt will not slip at the shoulder…. High-grade sporting rifle stocks often have trap buttplates [such as] made by Al Biesen….”

While details differ, rifle to rifle, Biesen stocks are recognizable. A full, rounded comb nose with low, perfectly cut flutes is one hint. Grips are properly slender, with just the right curve and taper. Fleur-de-lis checkering brings him quickly to mind. According to O’Connor, “Alvin Linden introduced patterns based on the fleur-de-lis, which has become very popular. This pattern is used almost exclusively by Al Biesen…. Incidentally, Linden almost never used exactly the same checkering pattern. At one time I had about a half-dozen Linden-stocked rifles, but no two patterns on them were alike…. Linden, Biesen and some other talented checkerers have frequently recessed their checkering patterns into the wood about 1/32 of an inch. To me this seems very handsome.”

A stock by Al Biesen is distinctive the way Michelle Pfeiffer is easy to tell from other beautiful blonde actresses.

“Hunting has changed a lot,” Biesen told me 23 years ago. “It doesn’t captivate youngsters as it once did, and there’s certainly less hunting opportunity for them. I’ve had fun helping young people into the shooting sports. I volunteered as one of the state’s first Hunter Education instructors, and helped start Spokane’s Inland Empire Big Game Council. I’ve donated $4,000 to improve the range where you shoot prone matches on the river. All good investments in the future of hunting and young people.

“Before the war, very few people went on safaris. Now most published hunting stories are about expensive hunts for records-book big game. You don’t see articles on rabbit hunting. Here and abroad, hunting has become much more expensive. Soon, I fear, only the very wealthy will be able to hunt. That’s how it is in Europe. I’ve shared camps with hunters who’ve hunted around the world. Some are wonderful companions. Others give you heartburn. Their collective net worth would astound you. I’ve profited from hunters like Prince Abdorezza Pahlavi of Iran. O’Connor introduced us. The prince bought a couple of rifles from me because he couldn’t hit with his Holland & Holland. After he left the throne, he ordered five more. The money from people like the Prince does great work for wildlife and for hunting. Sadly, the price of ordinary hunting is driving it beyond the reach of ordinary people.”

Allowing that Jack O’Connor’s sheep-hunting exploits with Biesen rifles was good for his shop, Al had little good to say about the race for records-book animals. “When I started hunting, any mature deer was a prize. Now a lot of hunters seem to be chasing celebrity. They want ‘slams’ of multiple species to win awards. Ego can make hunting an exercise in collecting.” Al told me that after a decade waiting for a pronghorn tag in a top Wyoming unit, he passed up an outstanding buck to give his pal the shot. “That was a good hunt!”

Bird hunting appealed to Biesen after big game lost its allure. He and Roger kept a goose lease on nearby Coffeepot Lake until that land went public. “When I was newly married, I even considered raising bird dogs for a living. I enjoy watching dogs work. I like the feel of a Parker.”

In 2002, five years after our chat, Al lost Genevieve, his wife of 65 years. “He took it hard,” said Roger then. “Dad and Gen were close.”

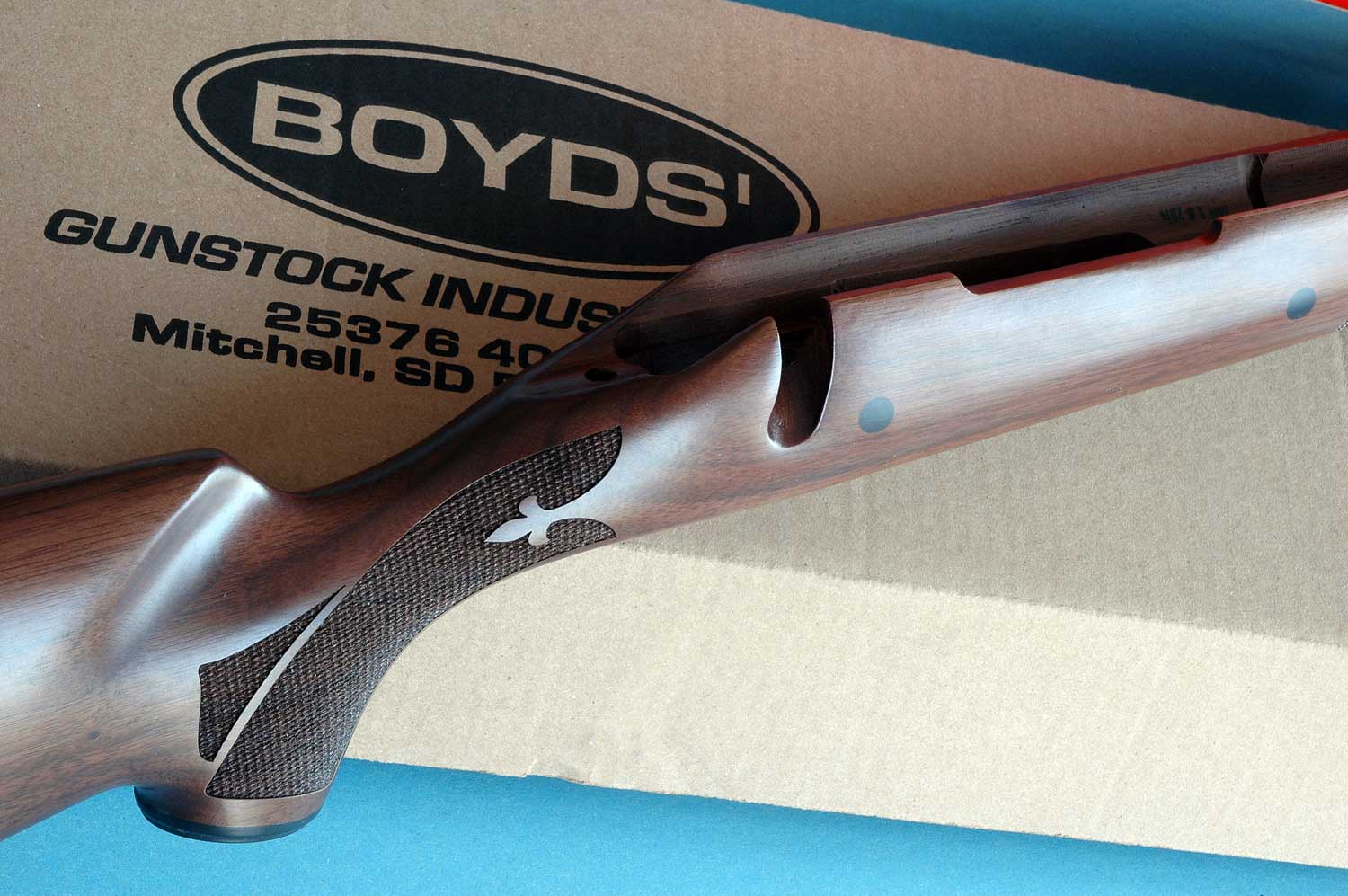

The shape and detailing of this Boyds after-market stock owe much to the likes of Biesen in the ’40s.

The shop stayed busy, Roger taking an increasing share of the load as hand tremors began to limit Al’s work. The focus on fine walnut-stocked bolt rifles remained. Neither Al nor Roger wanted anything to do with synthetic stocks—though Roger marveled at the rocketing price of figured walnut: “I just paid $2,250 for a blank! We used to sell finished rifles for that!” During the 1960s and ’70s, Sacramento wood supplier Joe Oakley had furnished much of Biesen’s walnut. After Joe died, Al and Roger bought suitable blanks from Ed Preslik, also in California, and Ed’s son Jim.

While many customers still asked for “a sheep rifle like Jack O’Connor’s,” Roger noted that both their tastes and expectations were changing. “We had a run on Ultra Mags. Short magnums too. I’d advise short-magnum fans to buy a factory-built rifle. Why rework a Mauser or early Model 70 action? For that matter, belted magnums may still be the best ever designed, and they work through magazines developed in the 1950s.” He added that magnums in general are over-sold. “You won’t find a better deer or sheep cartridge than the .30-’06 or .270.”

As to hunting-rifle accuracy, neither Al nor Roger thought much of five-shot groups measured to the third decimal. “A tight knot drilled over sandbags tells little about a hunting arm,” Al insisted. “Few if any game animals are lost because a rifle shot into 1 1/2 inches instead of an inch. What you need is a stock that fits and a rifle that balances well in hand, so the sight finds the target fast and stays there.”

Al’s attention to all aspects of custom rifle work served that mandate. “Grandpa prided himself in doing all the work,” said Paula Biesen-Malicki, Roger’s daughter. “He wasn’t just a stocker. He installed safeties, tuned triggers and altered bottom metal and magazines. For years he even did the bluing! If he needed a special tool or fixture, or a hard-to-find part, he was as apt to make it as buy it.”

Roger followed in that vein. Paula contributed a new element to Biesen rifles. “I had no artistic ambition,” she said, “until, by accident, I joined a junior-high painting class.” Her first watercolor wound up in the Governor’s office. After graduating from a local college in 1990, she took up engraving.

Her apprenticeship in the Biesen shop was enlightening. “Right away I found steel less forgiving than watercolor boards! Then there was Grandpa’s standard. He’d show me a Terry Wallace floorplate and tell me to come up with something like that! He might as well have told me to paint the ceiling like the Sistine Chapel’s!”

In 1992 the pretty blonde married David Malickie. They stayed in Spokane, and Paula refined her technique. “Knowing what not to do helps. Like never setting an animal face-on so you must duplicate its features, left and right. Beyond that, you must learn to coax life from steel. There’s no explaining how to do that. The chisel must work magic to bring from an inanimate surface the perception of color and depth, of shadow, temperature, soft texture and a glint in the eye!”

Soon Paula’s work would earn respect from the most critical eyes in the custom rifle business. “I was paid the greatest complement when Grandpa asked me to engrave a rifle he’d built for himself, a .30-06 on a Model 70 action. The wood was knock-out French he’d stashed in ’68. An irreplaceable rifle.”

Not long before he suffered a stroke in 1999, Al built for Paula a maple-stocked 1909 Mauser in .257 Roberts. “I knew it would be one of his last,” she said, “and it was some time before I worked up the courage to scratch it with a chisel.” Eventually she did, her masterful work adding images of Stone’s and desert rams on the floorplate, a Rocky Mountain bighorn on the grip cap and O’Connor’s Pilot Mountain Dall’s ram on the butt-plate. A sheep rifle.

In Al’s last years, son Don, then Paula and her husband stayed in the Sinto Street house to help him battle Alzheimer’s disease as long as he could remain at home. Roger continued to build Biesen rifles on the bench that served his father. A few years ago, he shuttered the basement shop.

Al Biesen died April 14, 2016, age 98.

Of Guns, Words and Life

As a youngster I thought Jack O’Connor had a great life. So I wrote him and asked what advice he might have for an aspiring writer.

I didn’t expect a reply. Jack surely got lots of mail. He couldn’t respond to all of it. But he sent me a full-page, hand-written letter.

I’d published nothing of note—was driving a ’63 Peterbilt log truck in the Wallowa Mountains above the confluence of the Imnaha and the Snake. But Jack composed a letter to me! Journalism won’t make you rich, he wrote, and plenty of people want to write about guns. You must know a lot, but never pretend to know more than you do lest you be found out and discredited. He told me to persist, because editors would reject most of my work. He was right about that. But he added—and I may be recalling something he didn’t say, but he surely left this impression—that if I loved the language and worked hard to use it well, somebody would eventually buy what I wrote. He had something there.

Alvin Biesen used his tools well and worked hard. He smiled a lot, gave generously of his time and talents and loomed large in a pantheon of gifted gunmakers, most of them now gone. Jerry Fisher, in Biesen’s time a promising young stocker, is “still making chips,” a sage of his craft. Gary Goudy, perhaps the best man with a checkering tool I’ve ever met, is still shaping stocks from scratch, but not as fast as I remember. The talent coming up to replace these masters is inspiring. The work of the best equals and in some ways surpasses what in my youth defined the apex of the art of gunmaking.

But Biesen’s era has gone, and with it the characters who gave it color—eccentrics whose secrets spilled with the stroke of a rasp over an oil-stained bench in a basement on Sinto Street.

Note: This article originally appeared in the 2020 Guns and Hunting issue of Sporting Classics magazine.

Michael McIntosh offers practical advice on buying, shooting and collecting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience. McIntosh also offers advice on buying and shooting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience.

Michael McIntosh offers practical advice on buying, shooting and collecting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience. McIntosh also offers advice on buying and shooting older guns–what to look for and what to look out for, all based on long experience.

As interest in fine double guns reaches a new high in this country, Best Guns serves as both a guide for the uninitiated and a standard reference for the experienced collector and shooter, all written with the precision and seamless grace that were Michael McIntosh’s trademark style. Buy Now