I had at first hoped to get my moose by fair stalking, without the help of calling, but I had long since abandoned that hope; and Willie, who was an excellent caller, had been doing his best, but with no result. We saw several cow moose, and once Willie called out a young bull, but his horns could not have had a spread of more than thirty-five inches, and he would have been quite useless as a museum specimen. Another time, when we were crawling up to a lake not far from the river, we found ourselves face to face with a two-year-old bull. He was very close to us, but as he hadn’t got our wind, he was merely curious to find out what we were, for Willie kept grunting through his birch-bark horn. Once he came up to within twenty feet of us and stood gazing. Finally he got our wind and crashed off through the lakeside alders.

As a rule, moose answer a call better at night, and almost every night we could hear them calling around our camp; generally they were cows that we heard, and once Willie had a duel with a cow as to which should have a young bull that we could hear in an alder thicket, smashing the bushes with his horns. Willie finally triumphed, and the bull headed toward us with a most disconcerting rush; next morning we found his tracks at the edge of the clearing not more than twenty yards from where we had been standing; at that point the camp smoke and smells had proved more convincing than Willie’s calling-horn.

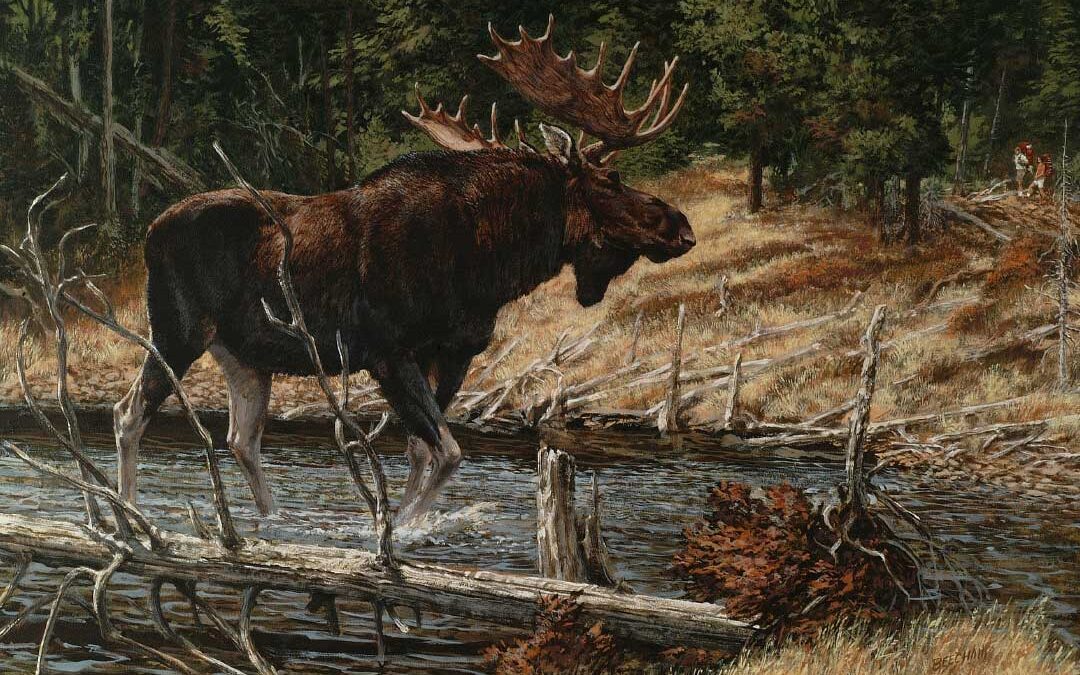

Shiras Prime by Greg Beecham, Oil on Linen, 30” x 48”

Late one afternoon I had a good opportunity to watch some beaver at work. We had crawled cautiously up to a small lake in the vain hope of finding a moose, when we came upon some beaver close to the shore. Their house was twenty or thirty yards away, and they were bringing out a supply of wood, chiefly poplar, for winter food. To and fro they swam, pushing the wood in front of them. Occasionally one would feel hungry, and then he would stop and start eating the bark from the log he was pushing. It made me shiver to watch them lying lazily in that icy water.

I had already stayed longer than I intended, and the day was rapidly approaching when I should have to start down-river. Even the cheerful Willie was getting discouraged, and instead of accounts of the miraculous bags hunters made at the end of their trips, I began to be told of people who were unfortunate enough to go out without anything. I made up my mind to put in the last few days hunting from the Popple Cabin, so one rainy noon, after a morning’s hunt along the river, we shouldered our packs and tramped off to the little cabin from which Bill and I had hunted. Wirre was with us, and we left him to dry out the cabin while we went off to try a late afternoon’s hunt. As we were climbing the hill from which Bill and I used to watch the little pond, Willie caught sight of a moose on the side of a hill a mile away. One look through our field-glasses convinced us it was a good bull. A deep wooded valley intervened, and down into it we started at headlong speed, and up the other side we panted. As we neared where we believed the moose to be, I slowed down in order to get my wind in case I had to do some quick shooting. I soon picked up the moose and managed to signal Willie to stop. The moose was walking along at the edge of the woods somewhat over two hundred yards to our left. The wind was favorable, so I decided to try to get nearer before shooting. It was a mistake, for which I came close to paying dearly; suddenly, and without any warning, the great animal swung into the woods and disappeared before I could get ready to shoot.

Willie had his birch-bark horn with him and he tried calling, but instead of coming toward us, we could hear the moose moving off in the other direction. The woods were dense, and all chance seemed to have gone. With a really good tracker, such as are to be found among some of the African tribes, the task would have been quite simple, but neither Willie nor I was good enough. We had given up hope when we heard the moose grunt on the hillside above us. Hurrying toward the sound, we soon came into more open country. I saw him in a little glade to our right; he looked most impressive as he stood there, nearly nineteen hands at the withers, shaking his antlers and staring at us; I dropped to my knee and shot, and that was the first that Willie knew of our quarry’s presence. He didn’t go far after my first shot, but several more were necessary before he fell. We hurried up to examine him; he was not yet dead, and when we were half a dozen yards away, he staggered to his feet and started for us, but he fell before he could reach us. Had I shot him the first day I might have had some compunction at having put an end to such a huge, handsome animal, but as it was I had no such feelings. We had hunted long and hard, and luck had been consistently against us.

Moose & Voyagers by Greg Beecham

Our chase had led us back in a quartering direction toward camp, which was now not more than a mile away; so Willie went to get Wirre, while I set to work to take the measurements and start on the skinning. Taking off a whole moose hide is no light task, and it was well after dark before we got it off. We estimated the weight of the green hide as well over a hundred and fifty pounds, but probably less than two hundred. We bundled it up as well as we could in some pack-straps, and as I seemed best suited to the task, I fastened it on my back.

The sun had gone down, and that mile back to camp, crawling over dead falls and tripping on stones, was one of the longest I have ever walked. The final descent down the almost perpendicular hillside was the worst. When I fell, the skin was so heavy and such a clumsy affair that I couldn’t get up alone unless I could find a tree to help me; but generally Willie would start me off again. When I reached the cabin, in spite of the cold night-air, my clothes were as wet as if I had been in swimming. After they had taken the skin off my shoulders, I felt as if I had nothing to hold me down to earth, and might at any moment go soaring into the air.

Next morning I packed the skin down to the main camp, about three miles, but I found it a much easier task in the daylight. After working for a while on the skin, I set off to look for a cow moose, but, as is always the case, where they had abounded before, there was none to be found now that we wanted one.

The next day we spent tramping over the barren hillsides after caribou. Willie caught a glimpse of one, but it disappeared into a pine forest before we could come up with it. On the way back to camp I shot a deer for meat on our way down the river.

I had determined to have one more try for a cow moose, and next morning was just going off to hunt some lakes when we caught sight of an old cow standing on the opposite bank of the river about half a mile above us. We crossed and hurried up along the bank, but when we reached the bog where she had been standing she had disappeared. There was a lake not far from the river-bank, and we thought that she might have gone to it, for we felt sure we had not frightened her. As we reached the lake we saw her standing at the edge of the woods on the other side, half hidden in the trees. I fired and missed, but as she turned to make off I broke her hind quarter. After going a little distance she circled back to the lake and went out to stand in the water. We portaged a canoe from the river and took some pictures before finishing the cow. At the point where she fell the banks of the lake were so steep that we had to give up the attempt to haul the carcass out. I therefore set to work to get the skin off where the cow lay in the water. It was a slow, cold task, but finally I finished and we set off downstream, Wirre in one canoe and Willie and myself in the other. According to custom, the moose head was laid in the bow of our canoe, with the horns curving out on either side.

Note: An excerpt from The Happy Hunting Grounds, published in 1920 by Charles Scribner’s Sons. Text made possible by the Biodiversity Heritage Library and the Library of Congress.

Here are some of the best hunting tales ever written, stories that sweep from charging lions in the African bush to mountain goats in the mountain crags of the Rockies; from the gallant bird dogs of the Southern pinelands to the great Western hunts of Theodore Roosevelt. Great American Hunting Stories captures the very soul of hunting. With contributions from: Theodore Roosevelt, Nash Buckingham, Archibald Rutledge, Zane Grey, Lieutenant Townsend Whelen, Harold McCracken, Irvin S. Cobb, Edwin Main Post, Horace Kephart, Francis Parkman ,William T. Hornaday, Sc.D, Rex Beach, and more. Shop Now

Here are some of the best hunting tales ever written, stories that sweep from charging lions in the African bush to mountain goats in the mountain crags of the Rockies; from the gallant bird dogs of the Southern pinelands to the great Western hunts of Theodore Roosevelt. Great American Hunting Stories captures the very soul of hunting. With contributions from: Theodore Roosevelt, Nash Buckingham, Archibald Rutledge, Zane Grey, Lieutenant Townsend Whelen, Harold McCracken, Irvin S. Cobb, Edwin Main Post, Horace Kephart, Francis Parkman ,William T. Hornaday, Sc.D, Rex Beach, and more. Shop Now

is that photo real? it looks the moose were added over the photo of a pound. still a great read!