In the afternoon one of the jaguar hunters—merely ranch hands who knew something of the chase of the jaguar—who had been searching for tracks rode in with the information that he had found fresh sign at a spot in the swamp about nine miles distant.

Next morning we rose at two and had started on our jaguar hunt at three. Colonel Rondon, Kermit, and I, with the two trailers or jaguar hunters, made up the party, each on a weedy, undersized marsh pony accustomed to traversing the vast stretches of morass; and we were accompanied by a boy with saddlebags holding our lunch, who rode a long-horned trotting steer which he managed by a string through its nostril and lip. The two trailers carried each a long, clumsy spear.

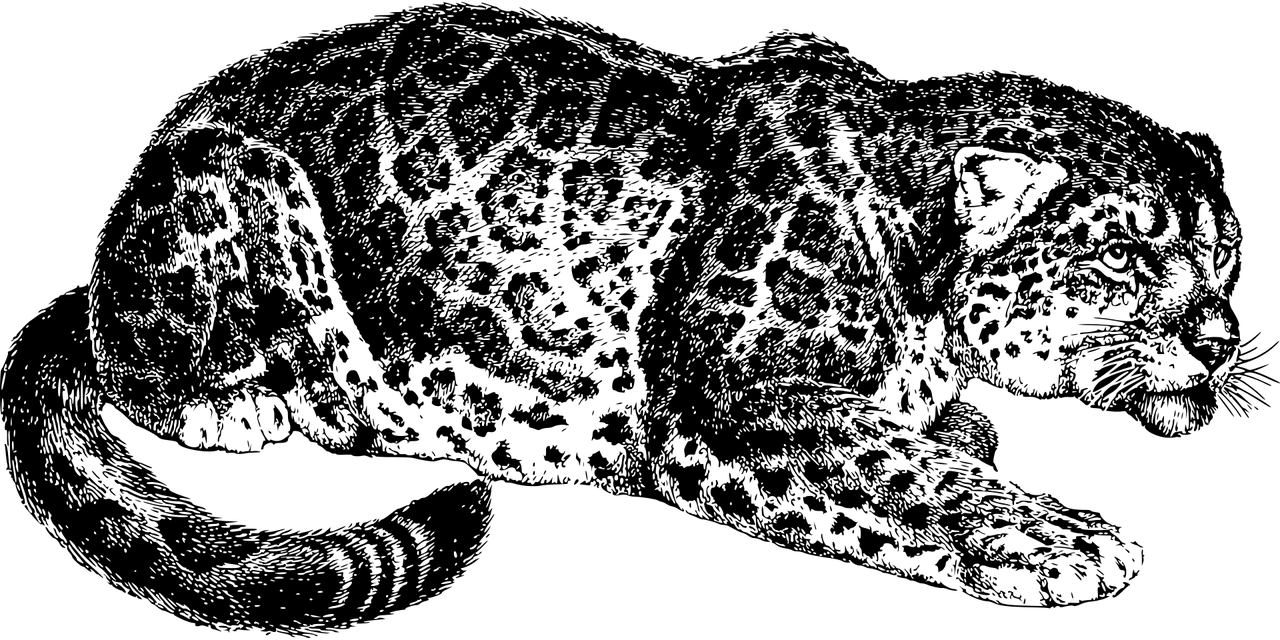

We had a rather poor pack. Besides our own two dogs, neither of which was used to jaguar hunting, there were the ranch dogs, which were well-nigh worthless, and then two jaguar hounds borrowed for the occasion from a ranch six or eight leagues distant. These were the only hounds on which we could place any trust, and they were led on leashes by the two trailers. One was a white bitch; the other, the best one we had, was a gelded black dog. They were lean, half-starved creatures with prick ears and a look of furtive wildness.

As our shabby little horses shuffled away from the ranch house the stars were brilliant and the Southern Cross hung well up in the heavens, tilted to the right. The landscape was spectral in the light of the waning moon. At the first shallow ford, as horses and dogs splashed across, an alligator, the jacaretinga (spectacled caiman), some five feet long, floated unconcernedly among the splashing hoofs and paws; evidently at night it did not fear us.

Hour after hour we slogged along. Then the night grew ghostly with the first dim gray of the dawn. The sky had become overcast. The sun rose red and angry through broken clouds; his disk flamed behind the tall, slender columns of the palms and lit the waste fields of papyrus. The black monkeys howled mournfully. The birds awoke. Macaws, parrots, and parakeets screamed and chattered at us as we rode by. Ibis called with wailing voices, and the plovers shrieked as they wheeled in the air. We waded across bayous and ponds where white lilies floated on the water and thronging lilac flowers splashed the green marsh with color.

At last, on the edge of a patch of jungle, in wet ground, we came on fresh jaguar tracks. Both the jaguar hounds challenged the sign. They were unleashed and galloped along the trail, while the other dogs noisily accompanied them. The hunt led right through the marsh.

Evidently the jaguar had not the least distaste for water. Probably it had been hunting for capybaras or tapirs, and it had gone straight through ponds and long, winding, narrow ditches or bayous, where it must now and then have had to swim for a stroke or two. It had also wandered through the island-like stretches of tree-covered land, the trees at this point being mostly palms and tarumans; the taruman is almost as big as a live oak, with glossy foliage and a fruit like an olive.

The pace quickened. The motley pack burst into yelling and howling, then a sudden quickening of the note showed that the game had either climbed a tree or turned to bay in a thicket. The former proved to be the case. The dogs had entered a patch of tall-tree jungle, and as we cantered up through the marsh we saw the jaguar high among the forked limbs of a taruman tree. It was a beautiful picture—the spotted coat of the big, lithe, formidable cat fairly shone as it snarled defiance at the pack below.

I did not trust the pack; the dogs were not staunch, and if the jaguar came down and started I feared we might lose it. So I fired at once from a distance of 70 yards. I was using my favorite rifle, the little Springfield with which I have killed most kinds of African game, from the lion and elephant down; the bullets were the sharp, pointed kind, with the end of naked lead.

At the shot the jaguar fell like a sack of sand through the branches, and although it staggered to its feet, it went but a score of yards before it sank down. When I came up it was dead under the palms, with three or four of the bolder dogs riving at it.

The jaguar is the king of South American game, ranking on an equality with the noblest beasts of the chase of North America, and behind only the huge and fierce creatures which stand at the head of the big game of Africa and Asia. This one was an adult female. It was heavier and more powerful than a full-grown male cougar, or African panther or leopard. It was a big, powerfully built creature, giving the same effect of strength that a tiger or lion does, and that the lithe leopards and pumas do not.

Its flesh, by the way, proved good eating when we had it for supper, although it was not cooked in the way it ought to have been. I tried it because I had found cougars such good eating; I have always regretted that in Africa I did not try lion’s flesh, which I am sure must be excellent.