Hunting any of Africa’s five most dangerous game species is a thrill like no other, but here’s why elephant hunting is number one on the list.

Which one of Africa’s Big Five is the most the dangerous game for hunting? It’s a question I often hear, and, without intending to sound trite, I might reply, “The one you happen to be hunting at the time.” Any one of Africa’s Big Five—elephant, rhino, buffalo, lion and leopard—is capable of inflicting serious injury or death. But when pressed for a more specific answer, the animal I consider most dangerous to hunt, especially in close cover, is unquestionably the elephant.

Hunting elephants is scary work, and anyone who claims it’s not is either a fool or a liar. To merely approach an elephant in thick bush can trigger a charge before a shot is ever fired. Moving to within spitting distance of an animal that can weigh as much as seven tons certainly commands your full attention and will have your heart pounding like a jackhammer.

When it comes to hunting dangerous game in Africa, there is no species more deadly than the aggressive bull elephant.

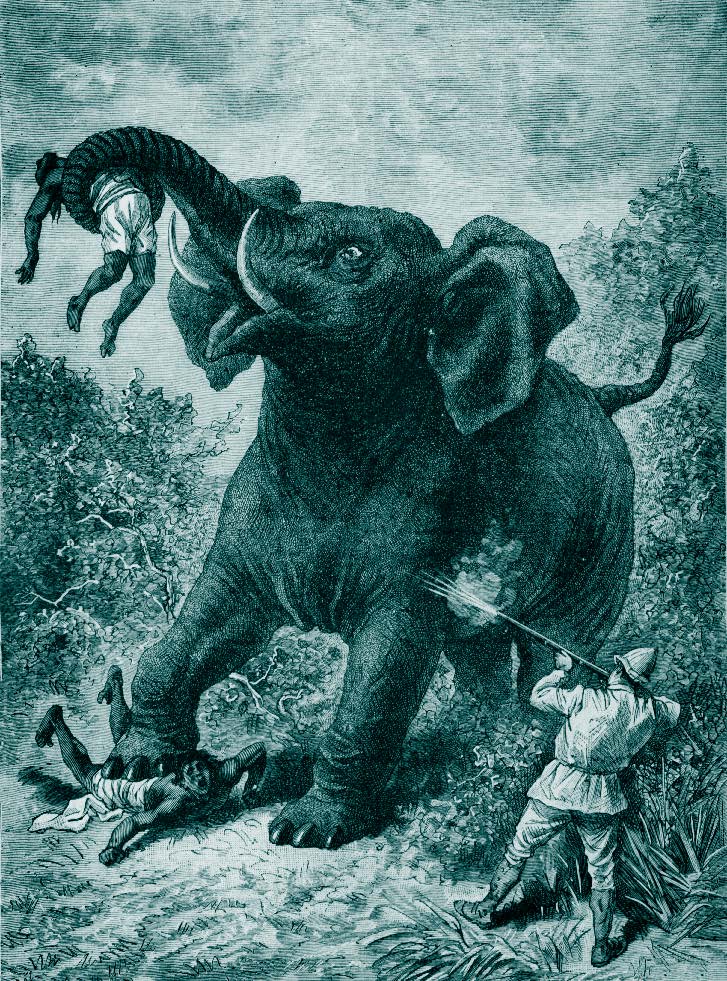

By virtue of their enormous size, strength and aggressive nature, elephants can kill you in a number of ways: they can break your neck or any other part of your body with the mere swat of their trunk; they can squash you flat by stepping on you and then do a little dance on your flattened torso; or they can skewer you on a tusk, running it through you like a sword—a thick pointed one that makes a very large hole in your body. Or they can combine all three methods during the same encounter.

Dangerous Game Hunting Gone Wrong

Each year in Africa, dozens of people are attacked by elephants and few survive to describe the traumatic experience of being knocked over, stepped-on or tusked by an elephant.

To my knowledge, the most extreme case of an elephant’s rage happened in Kenya back in 1973. It involved East African Professional Hunter Mike Kiley, who was guiding in an area north of the Tana River. They tracked a large bull into thick bush and closed to within 50 yards of the giant. Kiley lined up the client for a shot, who then fired. The elephant took off running and was quickly enveloped by the dense foliage. Kiley ran after the elephant, attempting to keep it in sight for a follow-up shot.

To my knowledge, the most extreme case of an elephant’s rage happened in Kenya back in 1973. It involved East African Professional Hunter Mike Kiley, who was guiding in an area north of the Tana River. They tracked a large bull into thick bush and closed to within 50 yards of the giant. Kiley lined up the client for a shot, who then fired. The elephant took off running and was quickly enveloped by the dense foliage. Kiley ran after the elephant, attempting to keep it in sight for a follow-up shot.

What happened next can only be surmised, but deciphering facts from the grizzly evidence at the scene, it appears that the elephant did not go far before stopping and turning to face his pursuer from only a short distance away. The bull charged Kiley who hastily fired a single, ineffectual shot at the bull, which grabbed and tusked him, then proceeded to tear him limb from limb. The bull finished the job by stomping and smashing Kiley’s remains into the ground. The elephant so thoroughly decimated Kiley’s body that the feet in his shoes were the only solid parts recovered from his scattered remains. Several days of extensive searching in the area failed to locate the elephant, which never was recovered.

It’s difficult for most people to imagine hunting an elephant unless they’ve actually experienced the excitement—and danger—of tracking one through thick African bush. But for those who have felt the surge of adrenal excitement in the final approach to a massive tusker, elephant hunting is the epitome of all sporting experiences. Many hunters consider the taking of a big tusker—one carrying more than 100 pounds per tusk—to be the pinnacle of achievement—the Holy Grail—in big game hunting.

The African elephant is larger than any other land animal by more than two tons, and in today’s world, the elephant seems an enigma—a holdover from the Pleistocene era. This may be why we’re so inexplicably drawn to them. Elephants provide a historical perspective for us, reminding us of the way the world used to be.

Ironically, a unique bone structure in the round, flat feet that carry his six- or seven-ton bulk biologically links him to a family of animals that weigh only six or seven pounds. The elephant’s closest African relative is a small, rock-climbing creature called a hyrax.

The Adventures of an Elephant Hunter

In the 1960s, my family moved to Kenya where my father and I were fortunate to have had the opportunity to hunt there. After a couple of years of pursuing plains game, we were eager to step up to the challenge of hunting elephants. In the beginning, we learned the ropes with the help of friends who were experienced resident hunters. Through them, we met several native Waliangulu trackers who were truly elephant experts and knew the countryside intimately. We were lucky, indeed, to have such a dream team showing us the way.

Moving beyond the initial learning period, my father and I were eventually licensed on our own merits to hunt four elephants per year, which we enjoyed doing for several years.

My elephant hunting continued in Botswana when I moved there in 1972 to begin professional hunting with Ker, Downey & Selby Safaris, managed by none other than Harry Selby, who had guided Robert Ruark on many safaris during the 1950s.

My elephant hunting continued in Botswana when I moved there in 1972 to begin professional hunting with Ker, Downey & Selby Safaris, managed by none other than Harry Selby, who had guided Robert Ruark on many safaris during the 1950s.

Hunting elephants with clients yielded many exciting and often dangerous encounters. At the time, I carried a post-’64 Winchester Model 70 “African” as my elephant gun. It served me reliably and dependably for many years, and in spite of the bad press the .458 Winchester Magnum cartridge often received, I always found Winchester’s largest round to be a capable stopper.

One particular incident stands out—the day that a Botswana elephant dramatically turned the tables on two safari clients and me. The hunt took place in 1976, and my client was Nico Van Rooyen, an experienced South African hunter and taxidermist with whom I’d done several safaris. Nico was accompanied by his friend, Sakkie van der Merve. Nico also carried a .458 in a Mauser-actioned, European-brand rifle.

It was an early season hunt primarily for elephant and buffalo. Botswana’s early season was mid-March through April, when the rains were usually at an end or winding down. The waterholes were brim-full, so the plains animals were scattered and able to drink anywhere they wanted. But it was an excellent time for hunting elephants because they didn’t need to travel far to eat or drink, and tracking them was reasonably easy in the moist sandy soil. It was ideal conditions for close encounters with elephants, the type of hunting Nico enjoyed.

Early season also meant plenty of long grass and bush that was thick with green leaves. Mopane trees were the dominant vegetation where we hunted, and both buffalo and elephant thrived in that country, using the leafy canopies for food, cover and shade. But it also meant you had to be close to an animal in order to see and judge the size of its horns or tusks.

At sunrise one morning, we located the spoor of two bull elephants and left the LandCruiser to track them through a thick mopane and acacia woodland. We’d followed the tracks for three or four miles before breaking out into a huge, wide-open plain of head-high elephant grass. We were at the southern end of the massive Mababe Depression and not far from the southern boundary of Chobe National Park.

One of my trackers climbed a tall mopane tree on the edge of the plain to have a look around. Eventually, he spotted two tiny specks on the horizon that he thought might be elephants. I climbed up for a look with binoculars and sure enough, it was the two bulls we’d been following. I could see they were feeding, but moving slowly toward a large stand of mopane where they could rest in the shade during the heat of the day.

I wanted to get to them before they ambled back into the trees where it would be difficult to locate their tracks again. If we were to reach them while still on the plain, we had to hurry . . . time was definitely of the essence.

I could not see the bulls when I climbed down from the tree, so I picked a spot on the horizon well ahead of where they were going and we started jogging toward it. If they continued at their current pace, I hoped to intercept them before they reached the trees.

It took us more than 15 minutes of non-stop running through coarse, saw-edged grass and low blackthorn bushes.

Fortunately, Nico and I were fit enough to keep up a good pace, but his friend, Sakkie, who was carrying a little more weight, fell behind. Nico and I had to keep going if there was any chance of getting to the bulls in time, so I had my second tracker, Galabone, stay with Sakkie, and they proceeded at their own speed.

Rich, my number one tracker, along with Nico and I, finally reached the bulls who were still on the plain, but edging ever closer to the woods. I felt something running down my legs, and looked to see blood trickling into my shoes. Our legs, badly scratched and cut from our run through grass and thorn, looked like roadmaps. Many months later, I was still scratching at festering sores as the thorns gradually worked their way out of my flesh.

The elephants were separated by a couple hundred yards, so with a favorable breeze in our face, we eased to within 30 yards of the largest bull who was farthest from the trees. The other bull was at the edge of the trees, which was a good thing as I hoped he would move on without the bull we were about to take.

Having taken a couple of previous elephants, Nico indicated he wanted to go for a side-on brain shot. Because of the degree of difficulty in picking out the proper point-of-aim as determined by distance and the angle and attitude of the head, a brain shot is not recommended for the inexperienced or first-time elephant hunter. From a flat side-on angle at 30 yards, Nico knew to aim at a spot exactly two inches above where an imaginary horizontal line extending from the eye intersects the vertical line of the ear.

At the sound of the shot, a single, well-placed bullet dropped the bull where he stood with no second coup-de-gras shot needed. We moved up to the downed elephant to admire a fine pair of 60-pound tusks. We could now relax and revel in the moment.

We were still back-slapping and congratulating each other when Rich signaled to me that the second bull was walking back in our direction.

The Risks of Hunting the Most Dangerous Game

Owing to a stiff breeze blowing from the bull to us, the second animal had not heard the shot and was now looking for his pal. He was walking directly toward us, so I recommended we retreat a couple of hundred yards to give him plenty of room to hopefully move away without further trouble.

But an uncomfortable feeling nagged at me—that this elephant was not going away without a fight, and I knew we would have some serious trouble on our hands if he came looking for us. There was not even a skinny tree anywhere around, or any cover that we could at least stand behind if the bull decided to look for us.

Then a cold shiver went down my spine as I remembered that Sakkie was still coming up from somewhere behind us, completely unaware of the impending danger that was increasing by the minute. The situation had become a dangerous mess in a very short amount of time.

As the bull came upon his dead companion, he reacted by moving up close to investigate the body with his trunk and immediately picked up our scent. His trunk then snaked skyward to search the air to determine where danger might be lurking. Next, he dropped his trunk and cocked his head as if looking at the ground.

Without hesitating, he began walking with his trunk extended and it was soon obvious he was following our scent like a bird dog tracking a covey of quail. The bull was coming for a showdown with a forceful and determined stride.

Standing in that field of head-high grass, with our rifles providing our only hope for survival, was a moment I shall never forget. There appeared to be little chance the bull would move off without trouble. He was on a mission and looking to settle a score.

I decided against firing a warning shot to scare the bull, afraid that it would more likely pinpoint our location and he would speed up his charge to get to us. There seemed no possibility of escaping a confrontation, which was rapidly becoming a matter of kill or be killed. We had clearly become the hunted.

Not the least of my worries was that if the elephant moved in the direction from which Sakkie was coming, I would have to make a move to intercept him. I backed the three of us up another 30 yards at an angle of 45 degrees away from the line of retreat we had taken from the dead elephant. I told Nico to be ready to shoot as soon as the elephant reached that point and turned to face us. We knew that would put him 30 yards away. Waiting until then gave the bull a final chance to move off without forcing a potentially lethal confrontation.

A frontal brain-shot on a moving elephant is never ideal, but when the bull reached the 30-yard mark, he turned to face us and hardly hesitated as he continued coming toward us, obviously following our scent. A frontal brain-shot was the only option.

“Take him now,” I said to Nico as we stood shoulder-to-shoulder, facing the oncoming bull that was knocking down tall grass as he came. Nico immediately fired, and I fully expected to see the bull crumple. I was shocked to see him break into a run, bearing straight down on us. Nico’s shot had clearly missed the brain and only served to infuriate the bull even more.

Taking down a massive, powerful bull elephant is the epitome of hunting dangerous game.

I was already aiming, and given the low, head-down angle he offered, I immediately fired at a point between and a little above his eyes. My bullet smashed through the thick cellular bone structure of the skull and penetrated the brain, causing the bull’s legs to buckle mid-stride. He pitched forward, shoveling his tusks into the ground less than 15 yards from where we stood. He’d covered half the distance to us in the time it took us to fire twice.

I wasn’t aware of it at the time, but what made the situation even more dire was that Nico’s Mauser-action rifle had jammed after the first shot when he tried to rack another round into the chamber. This clearly demonstrated why a backup rifle is so crucial when hunting dangerous game, and why it needs to be in a caliber capable of dropping an enraged elephant. Without a suitable backup rifle coming into play, this scenario might have had a different and almost certainly tragic ending.

“Hey, what’s all the shooting about? Why’d you shoot both elephants?” shouted Sakkie, who along with Galabone came up from behind us as the clouds of dust were settling.

“Sit down, Sakkie,” Nico said. “Have we got a story to tell!”

There’s always regret when an elephant goes down, but this time everyone felt much more than a twinge of remorse. When we finished the story, there was no backslapping, no excited congratulations to mark the occasion, just silent reflection.

Looking back upon that incident from so many years ago only increases my respect and admiration for the amazing elephant. We pride ourselves in accepting the challenges and dangers of hunting Africa’s biggest and most dangerous game, but other than war, how often are we the hunted? That day on the Mababe Plains we saw an elephant react with raw emotion to right a perceived wrong. As stressful and frightening as it was to survive the charge, we knew we’d witnessed something close to pure nobility in the actions of the second bull, the likes of which are rarely seen.

In addition to adrenaline-fueled tales of dangerous game hunting, Facing the Charge details how death was a constant companion on safari in the form of terrorists, quicksand, malaria and witchcraft, among other threats. It also analyzes how ivory traffickers have devastated the elephant population, examines the everyday hardships of life in Africa and pays tribute to the men and women who have made Africa a second home for author Michael Miller.

In addition to adrenaline-fueled tales of dangerous game hunting, Facing the Charge details how death was a constant companion on safari in the form of terrorists, quicksand, malaria and witchcraft, among other threats. It also analyzes how ivory traffickers have devastated the elephant population, examines the everyday hardships of life in Africa and pays tribute to the men and women who have made Africa a second home for author Michael Miller.

In her foreword, Fiona Claire Capstick, widow of legendary professional hunter and author Peter Hathaway Capstick, captures the essence of Facing the Charge, calling it “the stuff of high drama and retrospective hilarity,” while also noting that it showcases the “innate skills and knowledge of the African trackers, without whom no African hunting safari would be possible.”

Facing the Charge will appeal to both seasoned African hunters and novices anticipating their first safari, as well as to anyone who enjoys adventure in exotic locations. Shop Now