The 10 years or so of acquaintance with these two have left a powerful impression. My admiration remains.

Pieter still wears the same hat he was wearing when I first met him quite a few years back. But as for that, so do I. I suppose we both discovered that a good thing serves well and is not quickly supplanted. In stature, my brief 5’9” surpasses his by a good four inches. Otherwise, we could wear the same clothes.

Structures such as this are common in African hunting camps. These are sure to draw hunters at day’s end.

Pieter walks with an unusual gait but covers an inordinate amount of real estate just the same. In fact, it was Pieter I was struggling to follow when I had that first hint of heart issues. We were on the tracks of waterbuck — then a frightening chest disturbance. But even minus a blocked widow maker, I’m not sure I could have kept that steady, rocking pace. I had failed to do so two years prior when I was a healthy specimen.

And there is William — lanky, younger. I met him three years after I met Pieter. He is Pieter’s brother; both work for my PH friend Louis Steenkamp of Sofala Safaris. William glides when walking, an air of dignity present in every step. And like Pieter, he follows spoor in adroit fashion. A defined track here; a bent blade of grass there. It is said about men of the bush that they can track a bird across the sky an hour after that bird has passed. Hyperbole for sure, but not by much. Purely incredible, such trackers are.

Big rifles of various persuasions are found in the hands of PHs when hunting dangerous game. This one is chambered to .470 NE. Louis’ grandfather used it when he hunted the big stuff like elephant and Cape buffalo, and he passed the rifle on to Louis.

Pieter and William are part of the Sotho group (pronounced Sue-too). They are from the northern region of South Africa — Limpopo Province — where their tribe is known as the Pedi or Bapedi. They speak Sepedi. This is a dialect of the language known as Northern Sotho.

Since I struggled for some time trying to learn Spanish and still know only enough to get hurt, I find it captivating to encounter individuals who are bi-lingual or even multi-lingual. Pieter and William are so equipped. They can go from their Sotho dialect to Afrikaans with ease, and William is quite proficient with English as well. However, due to his rich, lyrical South African accent, I find myself asking him to repeat what he said far more often than he has to ask the same of me. He seems to understand Mississippi English just fine.

(Left to right) Louis, Fred, and Kinton follow buffalo spoor.

I chuckle often when I remember one early encounter I had with Pieter. He was sitting in the back of a hunting truck and in Afrikaans asked Louis how old I was. Louis interpreted and I responded. Louis then interpreted to Pieter, who simply hung his head and wagged it side to side. Turns out Pieter was a year older! I never concluded if his head wagging was an effort to commiserate or one of disgust that an old man such as I would fly half-way around the world to crawl through African thorn bush and red soil.

And I recall once when I sat at midday and watched William painting a portrait. Really, he was not painting; he was cleaning out the fire pit. He had a wheel barrow, a worn shovel, and a rake. Every move was fluid. He scooped, smoothed, raked and studied the situation. When he finished, the pit was a thing of beauty, even without the mystique of fire that would come at sunset. William, I then and there concluded, was an artist.

(Left to right) Fred, Kinton (kneeling), and Louis stop to consider options while looking for Cape buffalo. Louis’ big double, propped against a tree, is comforting. Fred carries his .375 H&H and Kinton has his 9.3X62.

Amazing it is that these men take whatever tools are available and accomplish impressive tasks. From plumbing to various equipment repairs, they get things done. I think back on childhood and consider other farmers such as we were. None of us had a great deal of anything except devotion to a multitude of waiting chores. A scattering of wrenches, pliers, hammers, pry bars, grease buckets and dirty hands sufficed. We made do and did well.

Late May and early June 2018, I was in Africa again, this time in rigorous and dangerous pursuit of Cape buffalo. It is an endeavor more suited for the young — and perhaps the foolish! The confines of age aside, I opted to give my best to these mysterious doings, and that best held the potential of being too little. But I found success and satisfaction in the collection of a fine bull, buff steaks grilled over an open fire and a truck load of superb meat delivered to those who needed it. Pieter and William were significant in each step of this process.

Kinton with his buff. The 9.3X62 worked well.

One incident of the make-do exemplified by Pieter and William occurred on that very day I collected my buffalo. There were a great many others over the years, but this one shines. Bull down, Pieter and William fetched a tractor and ragged trailer. They arrived, rattling along a two-track, approximately an hour after photos had been completed. We out-of-country hunters, three of us, wondered how this Goliath enterprise would be accomplished. No winches or techno-entrenched gear at hand. Just that battered trailer, a rusty chain hoist reminiscent of those attached to a limb or steel beam with a car engine dangling below that I saw as a child, and a tractor, this latter quite new and fully capable of heavy work. We three stood back and watched.

Pieter backed said trailer to the buff’s nose; William disengaged that rig from the tractor. The two men lifted the tongue skyward and propped it with a rough fence post. We observers watched and speculated as a plan came together.

Then the chain hoist. William attached one end to the trailer tongue, and Pieter attached the other to the buff’s boss. They commenced loading, the buffalo obliging by gliding into the trailer without protest. The only issue we unschooled three speculated upon was that the entire unit was still pointing up, the trailer now bearing perhaps 1,600-pounds of elevated weight. How to get it down and reattached? These men had the answer. They, via gesture, admonished us to gather round and grab any spot we could on the trailer tongue. It was a smooth process as the load flowed downward, teetering occasionally but solid.

(Left to right) William, Kinton, Fred, Sam, and Pieter pose with Kinton’s Cape buffalo.

Pieter felt comfortable enough with our long-term acquaintance to ask — in Afrikaans — the loan of my knife following the loading. He helped me understand by patting his belt line in the same spot from which my sheath hung. With that knife he made a small incision in the lower legs of the bull and tied them fast to a rail on the trailer. The buff was too long to fit completely, and this would keep the extended appendages secure. In the process he laid the knife down and exhibited a great deal of angst when he initially failed to locate it. I waved, in my best Afrikaans, a hand of what I considered a sign of all is well. Still, Pieter fretted. He wore a big smile when he picked my knife from the ground clutter.

I left Africa June 8, after that buffalo hunt concluded. My last trip to this point, and if age and health are truthful indicators, that last trip will be my last trip. Alarming to a degree, but I have elected to nurture the experience rather than mourn the probable.

Before I left, however, I located Pieter and William. I thanked them, shook their hands and said goodbye, awareness of a likely cessation concomitant with joyful retrospect, this ready to respond when summoned and energize a day when shadows lean curiously toward melancholy or when inescapable grief darkens the sunshine of an otherwise glorious day. The 10 years or so of acquaintance with these two have left a powerful impression.

My admiration remains.

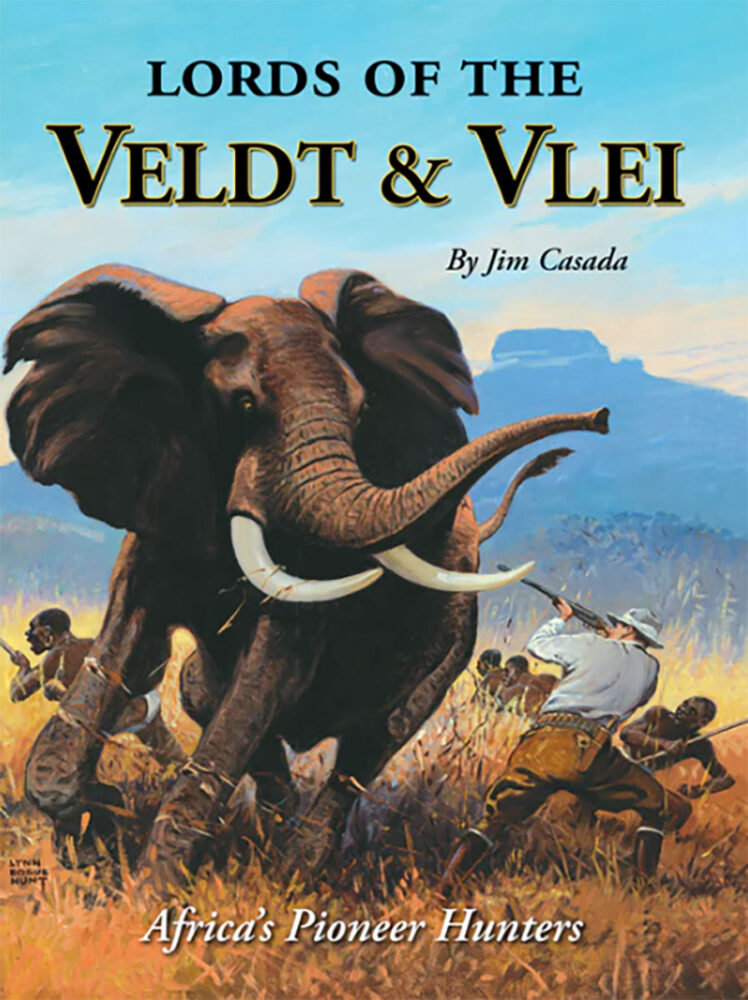

Well into the 19th century, most of the interior of tropical Africa was terra incognitae. Aptly styled the “Dark Continent,” wildest Africa was unknown, unexplored and unhunted. With the dawning of the Victorian era, however, all that changed. Driven by the allure of incredible hunting opportunities and the opportunity to win lasting fame through geographical discovery, intrepid individuals sought fame and fortune in the vast area where ancient maps carried notations such as “here be dragons.” Buy Now

Well into the 19th century, most of the interior of tropical Africa was terra incognitae. Aptly styled the “Dark Continent,” wildest Africa was unknown, unexplored and unhunted. With the dawning of the Victorian era, however, all that changed. Driven by the allure of incredible hunting opportunities and the opportunity to win lasting fame through geographical discovery, intrepid individuals sought fame and fortune in the vast area where ancient maps carried notations such as “here be dragons.” Buy Now