Many of the literary figures from the Victorian and Edwardian eras who hunted extensively in Africa and wrote about their experiences are virtual household names among today’s armchair adventurers. Foremost among them is Theodore Roosevelt, although obviously the totality of his career explains to a considerable degree why he has been the subject of dozens of biographies, several books dealing specifically with the sporting aspects of his life and endless fascination.

Then there’s Frederick Courteney Selous, the man many, with this writer being amongst their ranks, consider the greatest of all the African hunters. His enduring fame rests on many pillars—his exquisite touch as a writer, the romance of his life’s story, the fact that H. Rider Haggard’s fictional Allan Quatermain was based at least in part on his life (Selous even figures in one of the Indiana Jones presentations), his role as a pioneering conservationist (the sprawling Selous Game Reserve named for him) and his heroic death fighting in World War I when well into his 60s.

Or take J. H. Patterson, the author of The Lions of Tsavo and In the Grip of the Nyika, the subject of three movies connected with his dealings with man-eating lions at Tsavo (“Bwana Devil,” “Killers of Kilimanjaro” and “The Ghost and the Darkness”), inspiration for Ernest Hemingway’s “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” (also the focus of a movie, “The Macomber Affair”), a man whose military endeavors in multiple conflicts saw him earn the Distinguished Service Order and a major figure in early Zionism as commander of the Jewish Legion.

These individuals and at least some attributes of the Africa-related portions of their careers and the books they wrote about experiences in the Dark Continent are readily recognizable among the sizeable cadre of those devoted to reading about big-game hunting. Yet the name of a man whom all of these men knew, greatly admired, proudly called a friend and produced two excellent books on Africa along with a multitude of others, Abel Chapman, is virtually forgotten. I would maintain he deserves far better of posterity whether viewed strictly from the standpoint of his writings on sport or in the wider context of contributions to enduring literature on hunting and natural history.

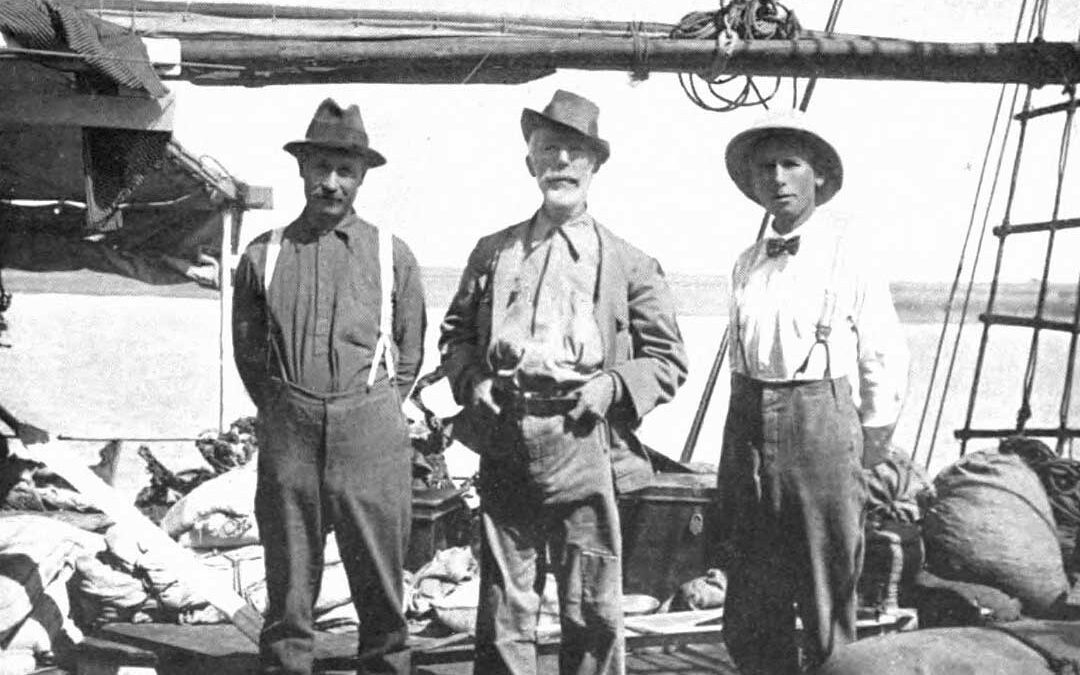

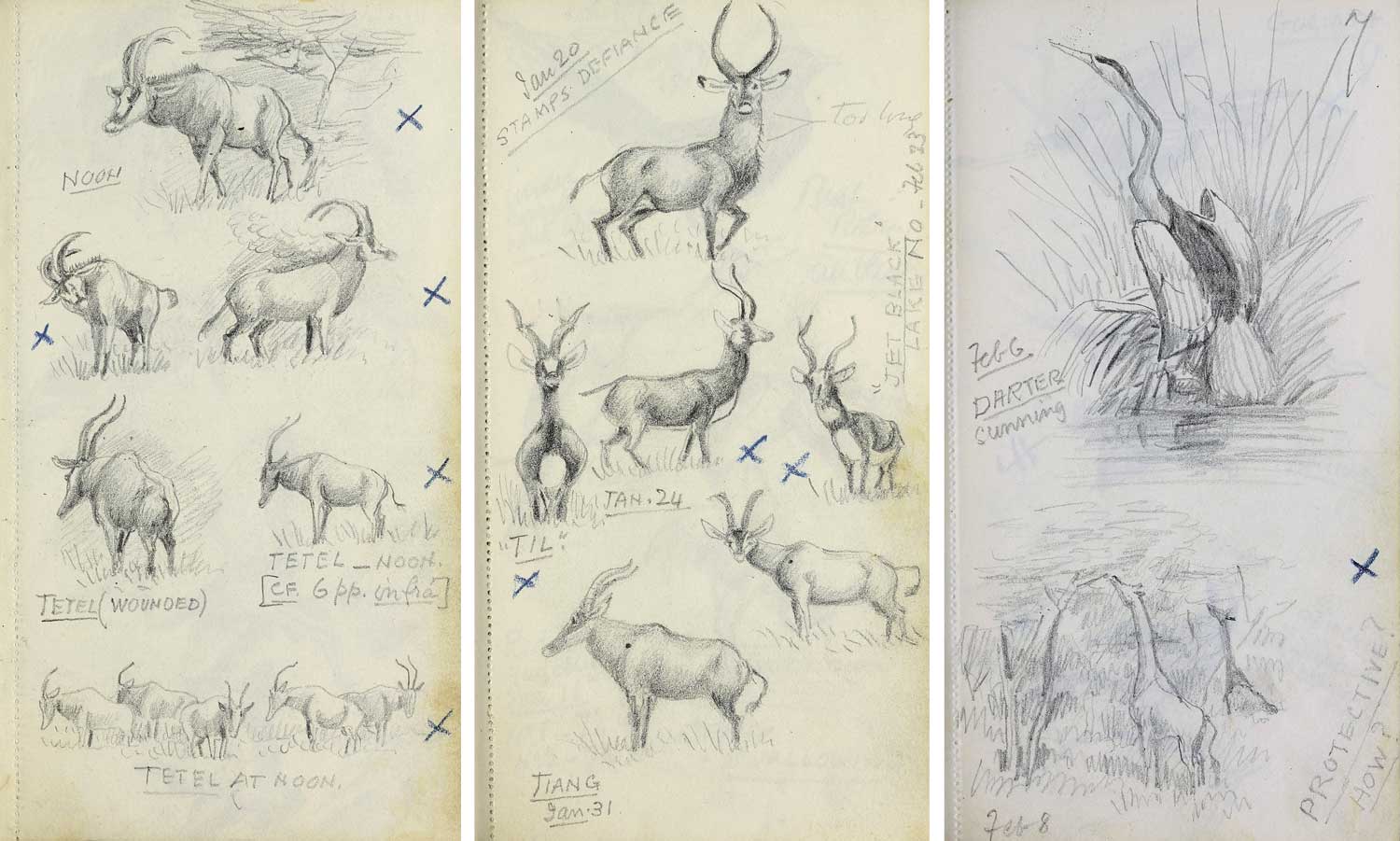

Abel Chapman was born on October 4, 1851 at the family home, Silksworth Hall, in Sunderland, England, the eldest of eight children of Thomas Edward Chapman, an affluent businessman, and his wife. Among his relatives on the maternal side of the family were Joseph Crawhall, a noted wingshot at grouse, and George Crawhall, described by his nephew as “a typical sportsman of the old school [and] the mentor to whom I owe the best grounding in field-craft.” Another Crawhall relative was his cousin, Joseph, who became a renowned artist. Chapman possessed considerable artistic skill in his own right, and most of his books include what he unassumingly styles “rough sketches.” They are actually nicely rendered, eye-catching illustrations.

He was educated at Rugby, where Fred Selous was one of the older boys in residence and where their lifelong friendship and shared interests first began to develop. Following completion of his studies at Rugby there are a few years in his life that seem sort of a biographical blank. After completing his schooling, Abel began work in the family’s enterprise, T. E. Chapman & Sons, which involved brewing along with importation and marketing of wine. He eventually became an active partner in the firm and, with the death of his father in 1875, served as head of the operation until selling the company and retiring in the late 1890s.

From his earliest adulthood onward, Chapman regularly found time for sport and travel along with work. A fair amount of this focused on the Iberian Peninsula where dealings in wine importation combined quite pleasantly with jaunts afield. A lifelong bachelor, he could call idle hours strictly his own and, once he retired, Abel utilized comfortable financial circumstances and his penchant for sport to great advantage. His travel, hunting, wildlife observation, interest in conservation and literary production, already impressive, all expanded significantly. The end result was a many-sided legacy that involved books and other arenas.

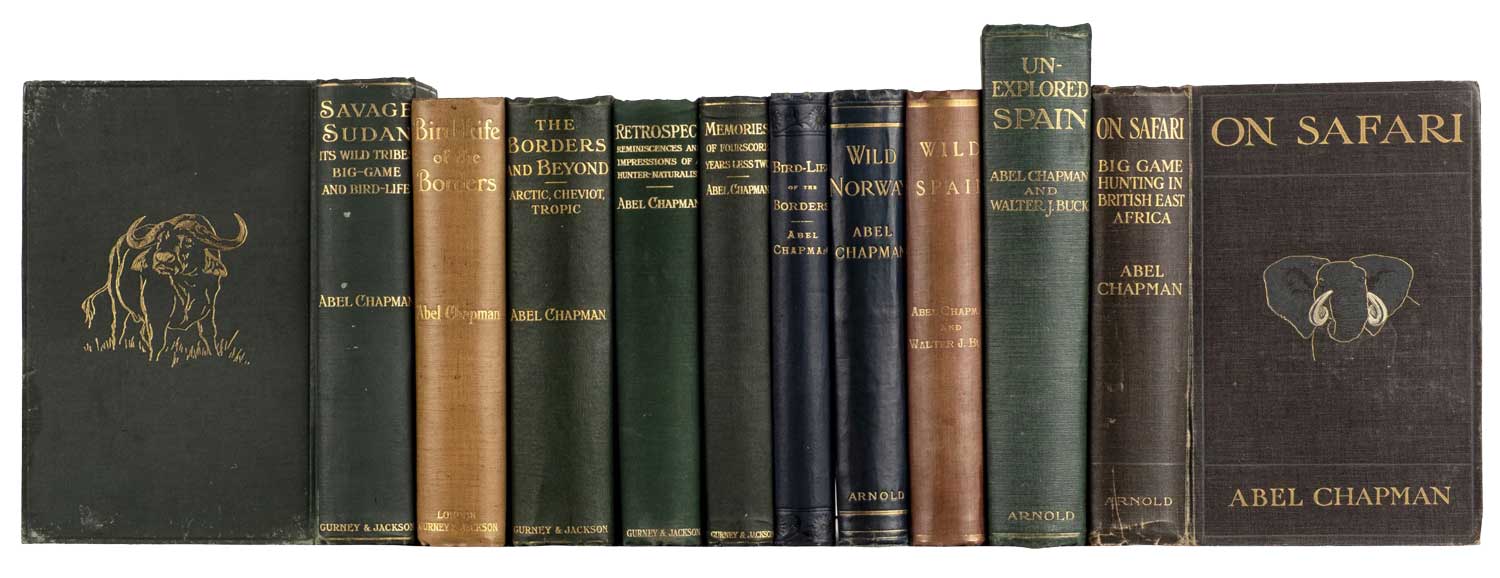

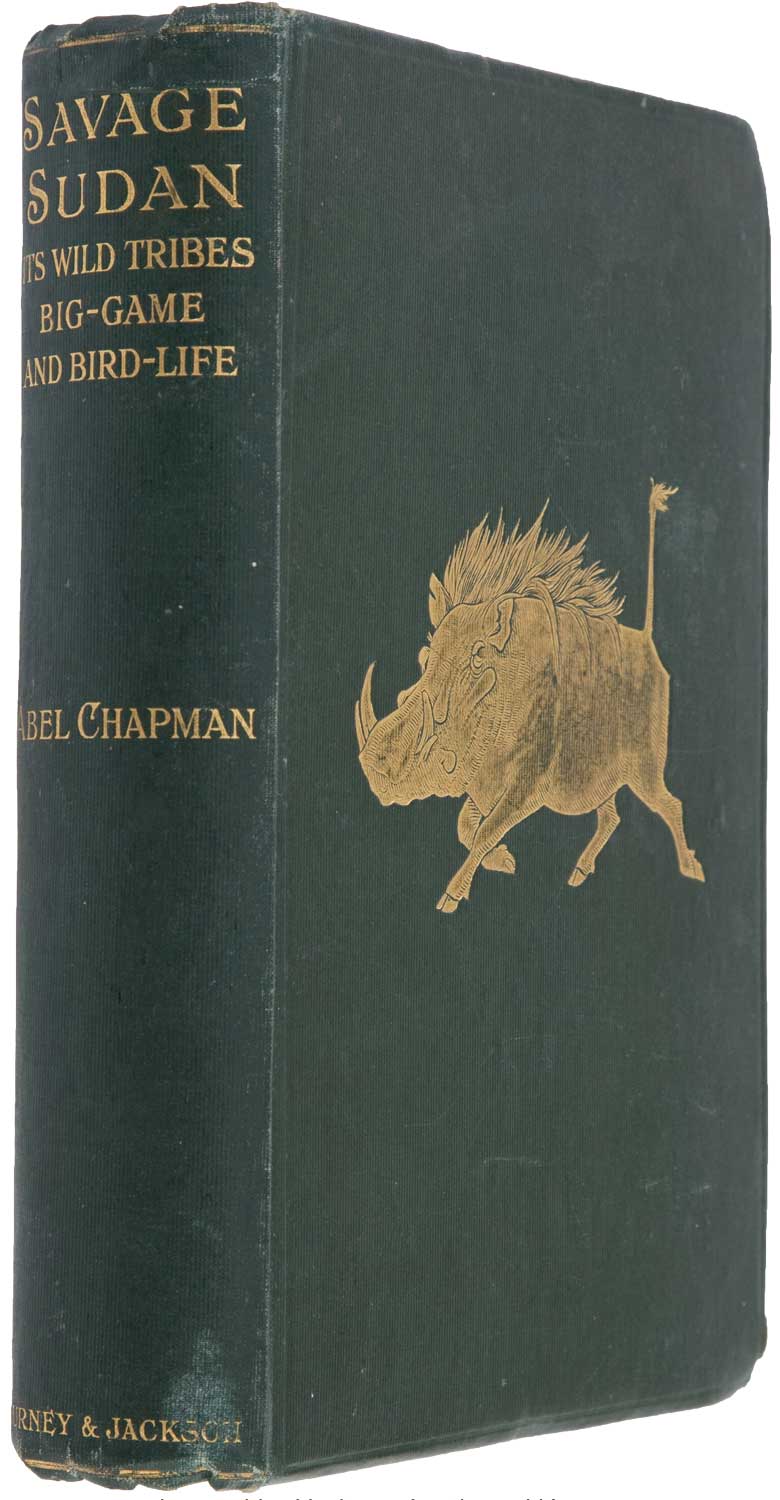

Altogether Chapman produced 10 original works touching on some aspect of hunting or the natural world. They were, in chronological order by original date of publication, Bird-Life of the Borders (1889); Wild Spain (with Walter Buck—1893); First Lessons in the Art of Wildfowling (1896); Wild Norway (1897); On Safari (1908); Unexplored Spain (with Walter Buck—1910); Savage Sudan: Its Wild Tribes, Big Game and Bird-Life (1921); The Borders and Beyond: Arctic, Cheviot, Tropic (1924); Retrospect: Reminiscences and Impressions of a Hunter-Naturalist in Three Continents, 1851-1928 (1928) and what is to an appreciable extent the same book published posthumously with a different title and including a memoir by George Bolam, Memories of Four Score Years Less Two, 1851-1929 (1930). He also figured prominently as a contributor to some of the massive multi-volume anthologies that enjoyed great popularity early in the 20th century, with British Game Birds (1910) and The Gun at Home and Abroad (1912-1916) being of particular note.

Many of these works include sketches by Chapman and almost all feature other artwork as well. They are enjoyable to read—chatty, relaxed and with a narrative style that carries the reader along vicariously in delightful fashion. Roosevelt considered Abel one of his favorite authors and in 1911 wrote a lengthy essay on six of his books that praised Chapman’s work in glowing fashion. From today’s perspective, the two most important Chapman books are probably those with an Africa focus, On Safari and Savage Sudan. In the original editions, both are collector’s items fetching prices of several hundred dollars, and even the leatherbound, slipcased and numbered limited edition of the former offered by Briar Patch Press in 1988 as part of The African Collection carries a value of several hundred dollars. An extensive Foreword by Mary Zeiss Stange adds to its overall appeal.

Along with being a prolific, highly capable and widely traveled writer, Chapman was also a visionary. His numerous visits to and research for books about Spain had impressive results. He formed a stellar friendship with another naturalist, Walter Buck, and together they created and oversaw the management of a nature reserve stretching along the Spanish coastline at Coto Donana. The area embraced the major European breeding ground for flamingos and proved critical in saving the Spanish ibex (a wild goat) from extinction. Indeed, some modern authorities give Chapman and Buck full credit for the survival of the Spanish ibex as a species.

Along with being a prolific, highly capable and widely traveled writer, Chapman was also a visionary. His numerous visits to and research for books about Spain had impressive results. He formed a stellar friendship with another naturalist, Walter Buck, and together they created and oversaw the management of a nature reserve stretching along the Spanish coastline at Coto Donana. The area embraced the major European breeding ground for flamingos and proved critical in saving the Spanish ibex (a wild goat) from extinction. Indeed, some modern authorities give Chapman and Buck full credit for the survival of the Spanish ibex as a species.

Another key conservation effort where Chapman’s efforts loomed large came in the creation of the Sabi Game Reserve (later a vital part of Kruger National Park) in South Africa. This was the result of him having observed, first-hand during a trip that was cut short by the Boer War, just how badly the Kruger area had been overhunted. On the home front, having moved to Houxty situated on the River North Tyne in Northumberland, in retirement Chapman created a sort of mini-nature reserve where he could be intimately involved in management and observation. He was particularly interested in improving blackcock (northern black grouse) populations, with the game bird’s presence having been a key factor in him purchasing and building his retirement home at Houxty. Chapman welcomed visitors, showing them how he had landscaped and planted to attract wildlife, and in many ways his retirement estate was an early model for wildlife management.

Theodore Roosevelt once wrote that Chapman’s “On Safari must be numbered among the best books that have been written about African big game” and praised the book’s author for the adroit fashion in which he combined “the abilities of sportsman, naturalist, and writer.” In many senses the latter part of that encomium goes to the heart of Chapman’s legacy. Today his books are missing from many supposedly representative sporting collections, and where present too often they reside in dust-gathering obscurity. The man and his work deserve better of posterity, and I think any reader who takes the time to read what Chapman left us will likely agree with that view and the thoughts of TR.

Longtime Editor-at-Large and Books Columnist for Sporting Classics, Jim Casada has written or edited dozens of books. The most recent, a longing look back on his youth, is A Smoky Mountain Boyhood: Memories, Musings, and More. It is available through the Sporting Classics Store or from www.jimcasadaoutdoors.com.

This article originally appeared in the 2021 Guns & Hunting issue of Sporting Classics magazine.