By Brent Lawrence, a public affairs officer for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Pacific Region in Portland, Oregon.

My Dad passed away on Dec. 22nd. A 90-year-old World War II veteran, he had a stroke on Halloween morning and it significantly affected his ability to communicate in his final weeks.

However, it couldn’t stop him from teaching me a final lesson about the outdoors.

Dad was never a particularly sentimental man. During a visit with him in Missouri last November, Dad and I mostly talked about his therapy, how I could help him while home, and the next steps in his recovery. Due to his speech problems, I would do most of the talking and he’d nod or work to get out a few words.

One day with most of our family visiting him at the rehabilitation facility, Dad started trying to talk. His words were particularly tough to understand because he was excited. Mom tried to understand him, but it was nearly impossible, with the words growing more unintelligible as his excitement level rose. Mom looked around for help translating, but my siblings could not understand him.

I could.

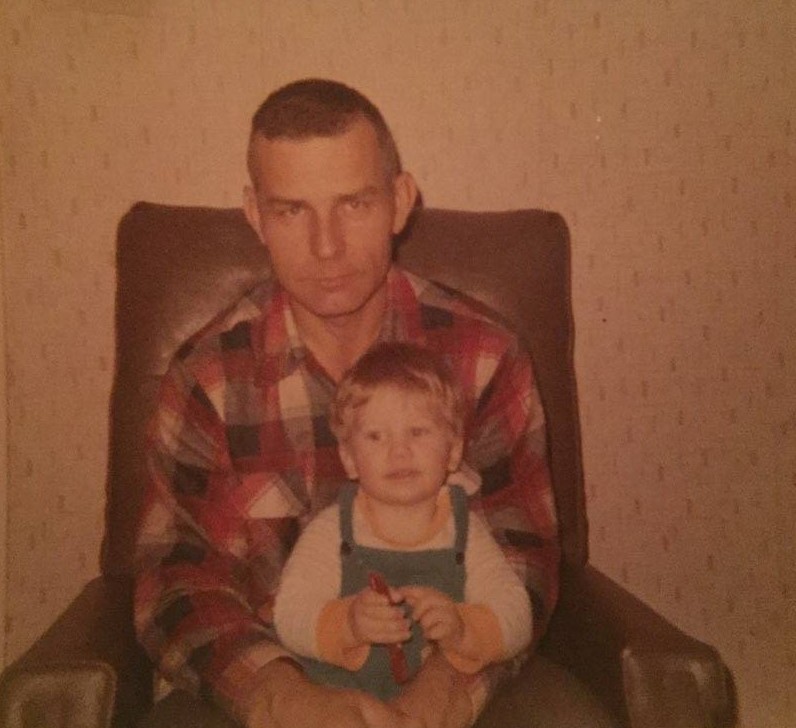

Albert Lawrence and his son (author, Brent Lawrence) as a 2-year-old in 1971.

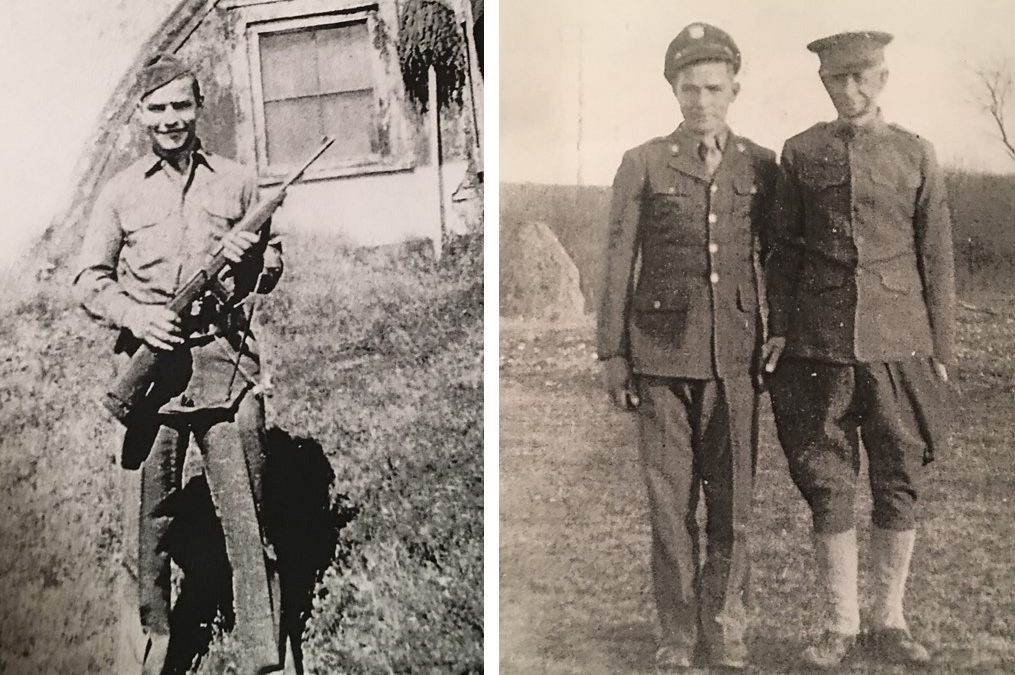

Albert Lawrence grew up on a southern Missouri farm during the Great Depression. He joined the military when he turned 17, and then returned home to get married, raise a family and work. Lots of work, often juggling a full-time job or two, and picking up side jobs mowing lawns, cutting trees or milking cows.

He never took time for recreation.

About 20 years ago, after Dad had finally retired from his full-time job because his knees were unable to withstand the daily grind of working on a loading dock, I took him on a duck hunt. It was a miserable day on Pomme de Terre Lake, so cold that the water would instantly freeze on the aluminum boat railing and our gloves. The ducks flew high that day, and we didn’t fire a shot.

We’d occasionally let Thunder, my chocolate Labrador retriever, run on the nearby island. He’d always take a swim in the frigid water, and his coat would freeze stiff when he climbed back in the boat.

Dad and Thunder had one thing in common that day – they loved that miserable morning. They were immersed in nature and the outdoors, and they were enjoying every single freezing minute of it.

Many times over the years Dad would bring it up, with a shine in his eyes and excitement in his voice. It always started with “Do you remember that time …” He would talk about Thunder’s icy coat and the frozen boat. He’d recall the ducks flying overhead and the bald eagles perched in the trees. He’d talk about it being so cold. He talked about it with a level of pure excitement that I rarely saw from him.

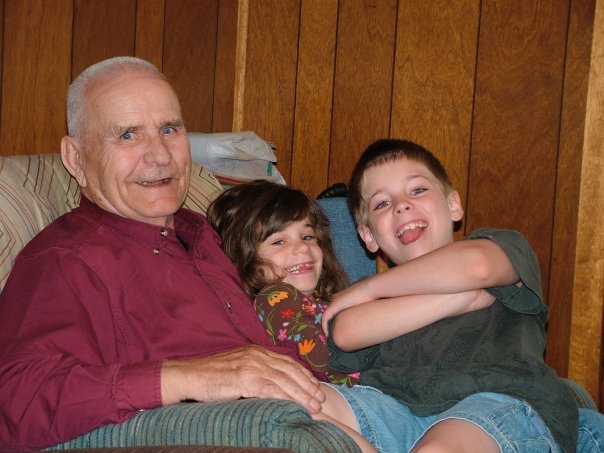

Albert Lawrence and the author’s children in 2006.

That frigid day on Pomme de Terre Lake is the only time I remember him slowing down and enjoying the outdoors. Memories of that day stayed with him to the very end.

So, there we were in a room full of people, and a man who couldn’t speak was trying to tell a story nobody else could understand. Except for me. The glow in his eyes and his excitement level said it all. I knew what he was trying to say.

I grabbed his hand and recounted the story. “Dad, do you remember Thunder’s icy coat and the frozen boat? The ducks flying overhead? And the extreme cold?”

He nodded in relief that I understood.

He remembered. We remembered. We cried.

Those memories, and many others, have sustained me in the weeks since his passing. Fortunately, there are many individuals who help create similar outdoor-related memories for me and many other people. I get to work with them on a daily basis.

There’s Rick Spring, the disabled U.S. Navy Veteran who has donated his time to build ADA-compliant hunting and birdwatching blinds at Ridgefield and Willapa National Wildlife Refuges. Rick builds blinds and he builds memories. He does it so that all people can experience the outdoors without limitations.

Dion Hess, the Lower Columbia Chapter of the Washington Waterfowl Association, and the staff at Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge worked together to put on the first Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge Veterans’ Day Waterfowl Hunt. They introduced 11 military veterans to the outdoors and hunting that day, giving them a gateway to the outdoors.

It was there that I met Sal Trujillo, a disabled Army veteran who was experiencing his first hunt. He was hunting from one of the ADA-compliant blinds that Rick built. Sal told me about the importance of outdoor recreation in helping him and other veterans stay away from “some pretty dark places.” Just as Dion started Sal down the path of outdoor-related memories, Sal now makes a difference by taking other veterans on outdoor excursions.

I witnessed Nancy Zingheim’s unyielding determination to fulfill the dying wish of a virtual stranger, all for the benefit and enjoyment of other people. Nancy’s inspiring 4,000-mile journey made sure that Rita Poe’s gift of nearly $800,000 to eight National Wildlife Refuges and four other parks in the West happened as promised. These two strangers managed to do something to help future generations connect with nature through conservation and outdoor opportunities on our public lands.

These people live and breathe conservation and wildlife, and they all go the extra mile to share that passion. They are creating memories of the outdoors.

I know that Dad remembered.

Rest in peace, Dad.