By all the laws of nature, George Blackwell should have quietly died of hypothermia in that very spot. But nature doesn’t always apply her laws with an even hand…

At about the midpoint of his 67th season, George Blackwell looked at the world around him and decided that it was good.

Just reaching a 67th season was satisfying enough, but being able to actually take part was better still. When his father had put a shotgun into George Blackwell’s 6-year-old’s hands, the boy found a calling and a passion that had deepened and mellowed in the man.

A modest family inheritance augmented by his own work as a painter of landscapes afforded George and Peggy Blackwell a comfort though by no means extravagant life. Also the snug white house on the leeside of a hill above the Little Skunk River. The view beyond the river from the broad, deeply roofed porch was of tall grass into a random bivouac of tent-like forms where cottontails spent winter nights. Oaks, maples and ashes, scarcely more than saplings when the house was built, now overtopped the gables, spilling deep shade.

Inside, the main level was once cavernous room — kitchen, dining and living room all in one. At its peak, the ceiling loomed more than 20 feet above the pine plank floor and its hand-braided scatter-rugs. A massive fieldstone fireplace occupied nearly one whole wall. Above the mantle hung a huge oil riverscape that George had painted for Peggy when the house was newly built. It showed a scene a few miles upriver, where sheer limestone bluffs faced lush forest across the river. It had been Peggy’s favorite place on the Little Skunk. A pair of deep, soft, leather-covered chairs faced the hearth. It was a good place to read, listen to music or the rain, or simply to sit and think.

Now, as November was shedding days from its second week, George Blackwell was sitting before a low fire, thinking of woodcock.

A soft northwest wind had blown for three days, then shifted to the south two nights ago. George Blackwell reckoned that flight birds riding the tailwind might well be taking a break in the coverts along the river.

“What do you say we have a look for doodles?” he asked the retriever, sprawled in the other chair. She flapped her tail a couple of times in reply.

“Thought you wouldn’t mind,” he said. George Blackwell often talked to the retriever as if to another person.

The Little Skunk was not a major flyway, but it consistently drew a few birds when the flight was on. To George Blackwell, having a look meant going out in mid-afternoon, when last night’s arrivals had had time to feed and loaf. It didn’t mean thrashing miles of river bottom, for George Blackwell had long since learned that the woodcock passing through preferred a few small coverts separated by goodly distances. Over the years, he had discovered a string of these both up and downstream, and he liked to approach them from the river.

After lunch, George Blackwell banked his fire, stuff the cuffs of his cotton brush pants into knee-high rubber Wellingtons and collected his gun and vest.

His canoe, a 16-foot Kevlar V-bottom, was tied to his little dock. In fall, this was his hunting boat. A padded, waterproof slip fastened to two thwarts held his gun, and a false transom made a place for his motor, an old-fashioned-looking outboard with horse-and-a-half power that was plenty for the Little Skunk’s mild current. Operating on the premises that motors could be balky and that anything in a canoe should be tied down, George Blackwell kept a pair of paddles lashed to the bulkheads. A little mesh bag for birds dangled from a hook under a gunwale.

His canoe, a 16-foot Kevlar V-bottom, was tied to his little dock. In fall, this was his hunting boat. A padded, waterproof slip fastened to two thwarts held his gun, and a false transom made a place for his motor, an old-fashioned-looking outboard with horse-and-a-half power that was plenty for the Little Skunk’s mild current. Operating on the premises that motors could be balky and that anything in a canoe should be tied down, George Blackwell kept a pair of paddles lashed to the bulkheads. A little mesh bag for birds dangled from a hook under a gunwale.

Presently, he and the retriever were motoring quietly upstream. If he had guessed correctly, there should be more than enough birds within two or three river miles of home. His plan was to start about four coverts upstream and float down to the rest.

As the first of the day, he chose a place that even an experienced woodcock hunter would likely have missed. Screened by the riverbank brush, it was a half-acre patch the birds chose for reasons all their own.

Today it was empty. The retriever covered every inch and came up birdless. George Blackwell searched the ground and found a few splashes of chalk, neither moist enough to be today’s nor powdery enough to have been left last week. He wondered for a moment if these birds leaving against a headwind might know something about upcoming weather that he didn’t.

Maybe so, he thought as they motored down to the next covert, because he noticed that the breeze had shifted into the west.

Even at that, the two birds in the next covert didn’t seem to mind. This was a place that even a blind hunter would recognize instantly for what it was —a patch of sycamore saplings about the size of a lady’s wrist, grown as densely as dog hair. It was a hard place to shoot in, but the retriever kicked up the first bird light on the edge and gave George Blackwell room to swing his 28-bore. The second bird was on the opposite edge and flushed far enough out that there was no shot to be taken. The little chap sprang straight up and disappeared into the treetops.

Back on the river, he could feel a stronger breeze now from the northwest, pushing decidedly cooler air.

The next covert was the largest in George Blackwell’s string of pearls — about an acre and a half with a nicely defined edge surrounding textbook habitat. Mercifully, it was far from the nearest road and the only hunting pressure it got was from his occasional visits.

As if to repay for the respite, the place today held better than a dozen birds, comfortably scattered.

Something, some faint message from the red gods led George Blackwell to pass up the first few shots, even though they were easy ones. The reason soon became clear when the retriever bumped up that rare and lovely sight — a double flush, two birds twittering up side by side at the same moment. George Blackwell took the right-hand bird as a quartering-away shot and killed the second just as it towered toward the treetops. The retriever had marked the first one, and when she brought it in, he hand-signaled her to the other.

Something, some faint message from the red gods led George Blackwell to pass up the first few shots, even though they were easy ones. The reason soon became clear when the retriever bumped up that rare and lovely sight — a double flush, two birds twittering up side by side at the same moment. George Blackwell took the right-hand bird as a quartering-away shot and killed the second just as it towered toward the treetops. The retriever had marked the first one, and when she brought it in, he hand-signaled her to the other.

It was only the second true double George Blackwell had taken in a lifetime as a woodcock hunter and he basked in the afterglow of the feeling as he and the retriever motored downstream toward home. It was a feeling composed of gratitude and pride, leavened with feelings that only hunters understand, feelings of having participated in tile natural cycle of life and death at a level not available to others.

George Blackwell never knew exactly what the canoe ran onto, only that his reverie ended abruptly as the port side rode high up on something, nearly spilling him over the starboard side. He would have served little purpose in trying to keep the boat from shipping water and simply sliding sideways under the river.

What George Blackwell did know was that his weight on the starboard bulkhead wasn’t helping the situation. He reached down and switched off the motor, lunged for the bow rope and missed it. With water beginning to flow over the gunwale, he took the only ship-saving measure he could think of and simply rolled over the port side. The retriever hit the water at the same time and began paddling toward the bank.

Free of unbalancing weight — and reaching the end of the sunken log — the little canoe righted itself and bobbed for a moment before the current floated it gently away. Standing nearly shoulder-deep in the river, George Blackwell could only watch it go for a moment before wading toward the bank. Ashe climbed up on my land, the retriever shook herself, and he thought for an illogical moment that the spray of droplets from her coat were especially beautiful backlit by the setting sun.

The next thought was considerably more logical: A setting sun meant the approach of night, and the approach of night meant the temperature was likely to fall. He already felt a frisson of chill ripple up his back. He pulled off his boots, poured out the water and put them back on.

He was about a mile from home, and it would be no cakewalk through the brush with only stars and a quarter moon for light. He wasn’t concerned about the canoe. About a quarter-mile above the house, a willow strainer reached well out into the river, The current would carry the boat into it as if into loving arms.

George Blackwell whistled to the retriever and the two of them set off along the riverbank.

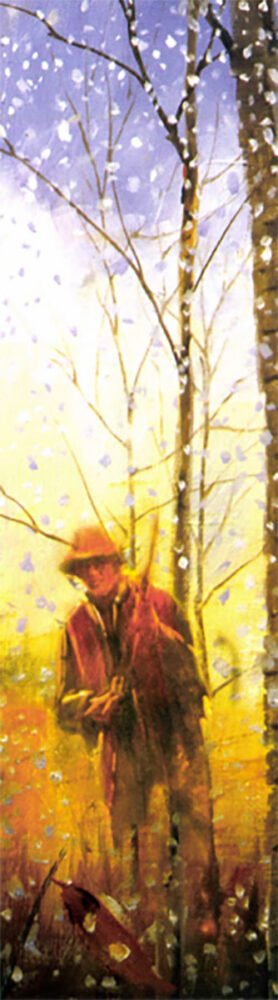

They hadn’t gone 200 yards before George Blackwell knew he was in for trouble. Daylight was nearly gone, and the night was coming on chilly. The brush was dense enough to make progress slow; he was losing body heat through his wet clothing faster than he could generate warmth by walking. He tried moving away from the river and into the trees, hoping to strike a brisker pace, but the maneuver didn’t help, for the going was just as slow. He began to shiver.

When the body loses heat to a certain level, it summons blood from the extremities to warm the vital organs. George Blackwell’s hands and feet were growing colder by the minute. He reckoned he wasn’t yet halfway home. The air grew colder.

Build a fire, he thought. The forest offered plenty of fuel, and he carried a butane lighter for his pipe. He found a dead branch and snapped off twigs, raked together some leaves and set up the beginning of a fire. That’s as far as it got. The lighter refused to render a flame; water in the valve no doubt. It would dry out eventually, but George Blackwell hadn’t the time to wait. In a fit of pique he flung the lighter toward the river. There was a sickening finality in the little plop it made, and he instantly regretted his rashness.

He was now shivering almost uncontrollably. He stumbled on downstream. As the body’s core temperature subsides, the mind loses its edge of clear thought and reason. When George Blackwell saw or thought he saw — his breath in the night air, he fixed on the notion of getting warm by taking shelter. Exactly where or how, he couldn’t have said at that moment, but shelter seemed his only hope. He was staggering now, stumbling from side to side like a drunk whose vertical time is running out.

Presently he found a little clearing, and in it a shallow depression in the ground, no doubt created by the toppling of some stately sycamore long ago. Now it served as a catch-basin for leaves from surrounding trees.

George Blackwell lay down in the depression and with his arms swept as many leaves over himself as he could. The retriever lay down beside him, pressing close to his belly and chest. He worked his stiffening fingers into her thick coat, now completely dry, feeling for the warmth underneath. He fell into a doze.

How long he stayed that way he never knew.

By all the laws of nature, George Blackwell should have quietly died of hypothermia in that very spot. But nature doesn’t always apply her laws with an even hand, and sometimes the mind and body rally together for a final effort at survival. In that moment, a lucid thought penetrated the haze gathering in his brain. He remembered that he had a pair of woolen gloves somewhere in his hunting vest. He carried a pair in each of his vests and jackets for hunting on the water, because wool retains most of its insulating properties even when wet.

It was perhaps not the most useful thought under the circumstances, but it was something to do, some reason to move.

He had to think for a while to recall where the gloves would be in this particular vest and settled finally on an inner pocket on the left-hand side. He was lying on his left side. Squirming like a man in a straitjacket, he managed to put enough space between himself and the retriever to open the soggy vest, fumbling at the buttons until they slid free.

His hand would scarcely articulate as he groped for the pocket, but he found it just as he remembered that it closed with a zipper. Finding the pull-tab he grasped it between his thumb and the middle knuckle of his index finger. Making the slide move took an enormous effort, and he felt its progress was glacially slow.

After what seemed a very long time, he could get his hand inside and feel the rough wool. As he clutched the gloves he felt something else in the pocket; it was small, hard and seemed made up of tiny pieces, and George Blackwell knew instantly what it was.

But first the gloves. Protected by the vest’s tightly woven cotton, they were merely damp. Getting them on was a struggle, and they left his fingertips bare, for they were fisherman’s gloves. But merely knowing that he was wearing something warm sent a small wash of energy to his mind. This he used to direct his hand back into the pocket in search of what he’d found. He worked his fingers inside the loop he expected to find, and drew it out.

It was a rosary.

Peggy had put it there who knew how long ago. She was gone six years now, but her practice of stashing rosaries in his hunting clothes had started early in their marriage.

George and Peggy Blackwell had never disagreed about religion, possibly because their approaches to God could scarcely have been more different. Peggy had been devoutly Catholic, wearing her faith like a comfortable old jacket. She liked the confines of the church walls, felt safe inside them.

George and Peggy Blackwell had never disagreed about religion, possibly because their approaches to God could scarcely have been more different. Peggy had been devoutly Catholic, wearing her faith like a comfortable old jacket. She liked the confines of the church walls, felt safe inside them.

She never insisted that George accompany her to Mass, but he did several times in the early days. He was intrigued by the ritual and enjoyed the music, but in the end he found no liking for dogma nor dispensations nor the hierarchy of Church politics. George Blackwell preferred to meet God face-to-face, in nature, which he devoutly believed was the finest creation that could ever be. They did not even agree to disagree; they simply respected one another’s beliefs and said no more of it after a single discussion.

“I see no reason,” she had said in her faintly Irish lilt, “why everyone should have to believe the same thing.”

“Even so,” he said, grinning, “I wouldn’t mind if you said a prayer for me now and then.”

“George Blackwell, I pray for your soul at every Mass.”

They never spoke of the matter again, but after that he began finding rosaries in his hunting clothes. When he asked her about them, she simply said, “Just to be sure someone’s watching over you when I can’t.”

Now he held one in his hand and knowing she was the last one to touch it, he felt a terrible pang of loneliness and loss. After a few moments, he grasped the beads as best he could and began murmuring what to his mind was the most beautiful of all Catholic prayers, one he loved both for the flow of its language and also because it reminded him of Peggy:

Hail, Mary full of Grace; the Lord is with thee. Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death. Amen.

He didn’t bother sliding a bead through his fingers. He wasn’t keeping count, only letting the lovely words float through his mind. He was midway in what would have been the second decade when the retriever suddenly leapt to her feet and uttered a soft growl.

She was facing the woods; slowly, painfully George Blackwell craned his neck to see what had caught her notice.

What he saw was a spot of light, and after a moment it seemed to be moving toward them. George Blackwell’s first thought was that the breeze was making some chimera from a wisp of fog off the river. But he was between the light and the river. Whatever the source, it wasn’t fog.

The light stopped moving a short distance away, and he could see that it was a woman dressed entirely in white, as bright as anything he’d ever seen. She seemed possessed of an inner radiance, light contained entirely within herself, light giving off no heat and casting no shadows around her. So dazzling was her presence that George Blackwell’s eyes needed a few moments to adjust. Her face and hands were as white as her robe. He could not distinguish her features, but somehow he knew this was not a vision of Peggy.

The retriever stopped growling and changing her mind, bounded toward the woman as if certain the woman had come just to play with her. But as the dog drew near she grew quiet and simply sat at the woman’s feet, gazing upward to her face.

George Blackwell lay as if transfixed, his mind struggling to comprehend this vision that seemed at once ethereal and solidly real. At length he heard a voice. It did not come from the woman in white, but rather seemed to fill the air around him.

It was Peggy’s voice, and although he could distinguish no words, the tone was unmistakable. Peggy was urging him to rise from what surely would become his death bed and continue on toward home.

With the help of a sapling he could reach, he climbed slowly to his feet, which felt as if it were carved from ice. He stood clutching the little tree as a drowning man would grasp a lifeline. After a few moments he released it and lurched a few steps in what he thought was the right direction. Slowly he gained confidence in his ability to stay upright and began moving with a sense of purpose.

The woman in white moved with him, staying a short distance ahead. The retriever frolicked in circles around her. Once, George Blackwell thought he saw the dog run through the woman’s robe, but he dismissed the notion as imagination.

They soon came to the willow strainer where he expected to find his canoe, and there it was, bobbing a bit sluggishly but still upright. He would fetch it tomorrow.

But the woman in white did not move, and George Blackwell once again heard Peggy’s voice. As before, there were no words, but she seemed to want him to take the canoe now. To do so he would have to wade into the river, and he recoiled from the thought as if burned. Still, the voice continued, at once insistent and reassuring. Finally, George Blackwell sighed and stumbled toward the water.

At the river’s first touch on his skin, he could not have said whether he felt excruciating cold or searing heat. The cold soon won out. Keeping to the shallowest water he could find, he finally was able to snag the bow rope and tow the boat into the shallows.

Clambering over the gunwale, he settled himself on the rear seat, switched on the fuel flow to the motor and pulled the starting rope. The little kicker refused to start. This was no time to clean and prime a carburetor, so he unlashed a paddle, thinking it was good he’d tied them in with single-pull knots.

The woman in white and the retriever watched as he paddled slowly along the strainer till the current caught the bow and turned the boat downstream.

He was clumsy at first, his blood-starved arms and shoulders unable to dig deeply or pull with much strength. The current helped keep the canoe moving, but George Blackwell was now close enough to home that he wanted to assist his progress as much as he could. Looking toward the bank, he could see the woman in white matching his pace.

At last, he passed the final willow slap upstream from his house and turned the boat toward the dock. The gunwale slid along the weathered planks, and when the bow crunched into the gravel, he stepped over the side into water that did not overtop his boots.

He tied the bow rope to a cleat and then simply stood looking at the house light burning on the porch. That light and what it represented made the previous hours seem unreal.

A fit of shivering roused him, and he trudged up the slope toward the light.

On the porch he turned. The woman in white had stopped a few yards away. The retriever sat beside her. George Blackwell wasn’t sure what to say. Nothing he could think of seemed adequate.

“Thank you,” he finally said. “Thank you.”

She raised a hand and sketched a sign in the air.

George Blackwell whistled softly for the retriever. She looked first at him and then at the woman in white. The woman made a tiny motion, and the dog ran up the porch steps and stood at the door, tail waving. He let her in, but when he looked back, the woman in white was gone.

George Blackwell whistled softly for the retriever. She looked first at him and then at the woman in white. The woman made a tiny motion, and the dog ran up the porch steps and stood at the door, tail waving. He let her in, but when he looked back, the woman in white was gone.

He tossed a couple of small sticks onto the bed of coals in the fireplace and hung his vest on the back of a dining chair. Everything else he left in a sodden heap on the floor. In a bathroom he toweled himself briskly and from a closet pulled along, quilted goose-down robe that Peggy had given him one year at Christmastime. He pulled a pair of sheepskin slippers onto his feet.

The sticks in the fireplace had caught, and George Blackwell built up the fire to a dancing blaze. From a closet shelf he lifted down a thick, four-point Hudson’s Bay blanket, unfolded it halfway. He sank into his leather chair, put his feet up, draped the blanket over them and pulled it up to his chin.

The retriever was already curled into her chair, but of a sudden she jumped up and stared behind them. For the second time that evening, George Blackwell turned to see what she was seeing — and caught a glimpse of radiant light just disappearing past a window frame. Presently the dog laydown, sighed deeply and slept.

After a time, warmth seeping into his body, George Blackwell slept as well — and traversed the dreamscape in pursuit of that woman in white.

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself.

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself.

Featuring both fictional and true-to-life adventures, these astonishing stories are from the creative minds of such legendary authors as Peter Capstick, Archibald Rutledge, Gene Hill, Mike Gaddis, Roger Pinckney and John Madson. Buy Now