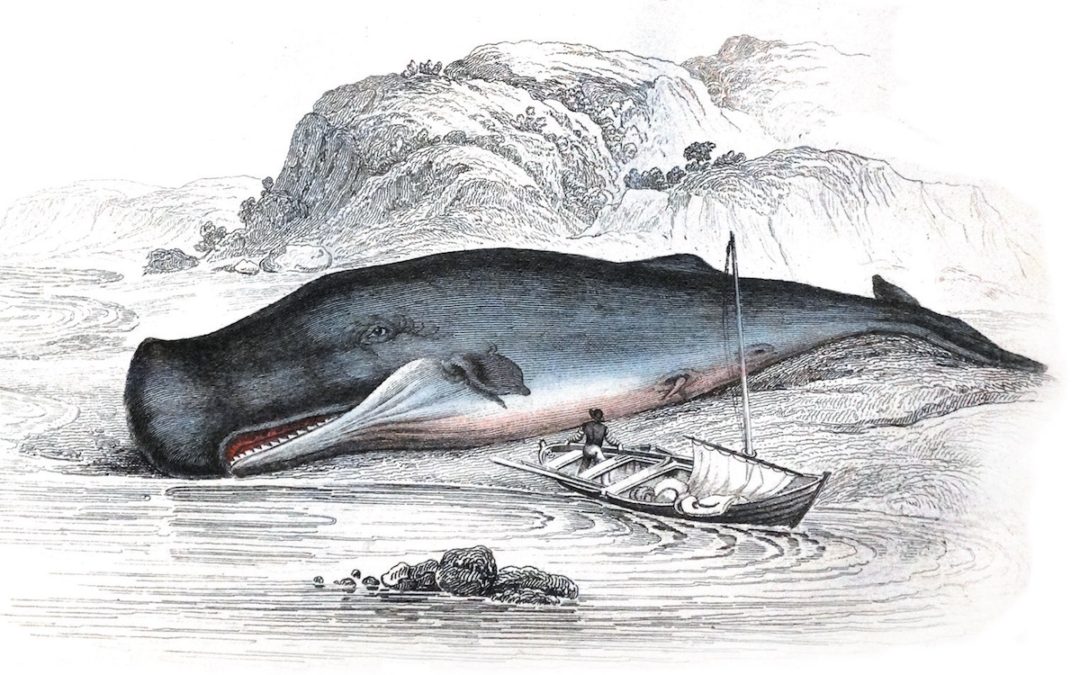

At 63 feet long and weighing more than 60 tons, the old sperm whale was truly a leviathan from the depths.

The bull’s ghost gray hide was worn from age and heavily scarred from decades of fights with deep-roaming squid and battles with rival males competing for breeding rights. It was perhaps the latter that pushed the bull from his pod and forced him to hunt the Gulf of Mexico alone.

He was pursuing a large school of squid when he suddenly found himself grounded in a mass of seaweed and mud in 12 feet of water. Unable to push forward, the bull thrashed violently and repeatedly slapped the brownish water with his 18-foot-wide tail in an attempt to free himself.

Some four miles away, standing atop his steamboat Florida, Captain Cott Plummer saw the commotion and decided to investigate. What he discovered in Oil Pound, three miles west of the Sabine Estuary jetties on March 10, 1910 would come to spark the interest of a nation, be witnessed by thousands of spectators and earn him a great deal of money.

Arriving at the scene, Plummer saw a monstrous animal sending geysers of mud and water skyward in its struggle. Standing in awe of the gargantuan, Plummer immediately concocted a whale of an idea. If he could pull the monster to the nearby town of Sabine Pass, he could make a fortune charging people to see his catch.

Determined to make his plan a reality, Plummer grabbed a five-inch hawser and quickly ran the cable to an approaching sailboat on the opposite side of the whale. Once connected, the two vessels moved toward the rear of the animal while dragging the cable through the soft mud beneath it. When the hawser reached the narrow part of the tail just above the fluke, Plummer cinched it tight and revved up Florida’s 350-horse engine.

The hawser snapped in two.

Undeterred, Plummer tried again, this time using an eight-inch hawser. The massive cable held and, with his engines pushed almost to the brink, he pulled the whale free of the mire. Once free, the whale came to life and thrashed toward deeper water, dragging the Florida behind it. Plummer increased the thrust and momentarily gained the upper hand.

The tug of war between whale and machine lasted the remainder of the day and turned the five-mile trip to Sabine Pass into an eight-hour ordeal that the whale ultimately lost. Plummer ended the day by victoriously tying his boat, and his whale, to the Southern Pacific Railroad docking slip.

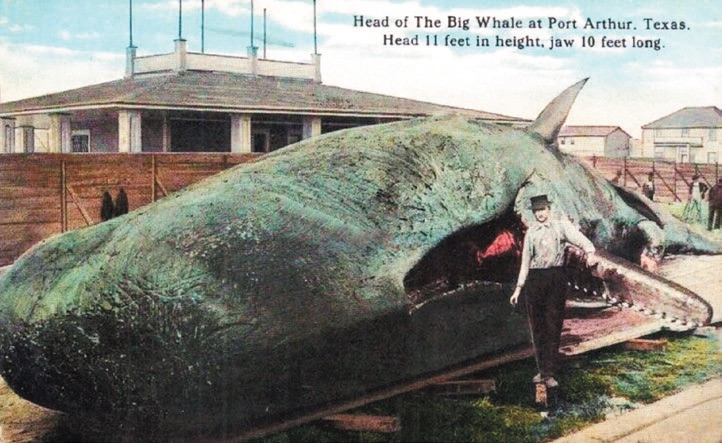

Before cameras were available to the public, postcards were a favorite way of sharing images like the giant whale at Port Arthur.

News of the captured whale spread like wildfire. Telegraph operators reported to newspapers around the country that Sabine Pass’ “Moby Dick” was 90 feet long and 300 tons of ferocious sea monster. The next day more than 400 people paid 50 cents apiece to gaze upon the leashed whale as it fought to free itself.

Seeing what a cash cow the whale could be, the neighboring city of Port Arthur negotiated a deal with Plummer to permanently exhibit the creature. The deal was made and almost immediately 100 carpenters descended on Port Arthur’s docks to build a corral and viewing platform.

On the afternoon of March 10, Plummer began towing his whale eight miles to its new home. At first the old bull repeated his tug of war actions from two days earlier but eventually succumbed to exhaustion and died.

Having already invested so much money and effort on the display, the city of Port Arthur came up with a second idea. On March 11, several hundred workmen began digging a ramp that would allow the dead whale to be towed on shore and onto a waiting stage for display. That afternoon, with the stage nearly completed, a series of steam winches pulled the dead whale ashore where a team of 20 butchers waited. The men worked feverishly to remove the animal’s internal organs so the cavity could be packed with ice. To further delay deterioration, barrels of embalming fluid, potassium permanganate and other preservatives were pumped into the animal’s huge body.

As the army of men worked on the carcass, Dr. Newman, a state zoologist, seized the chance to make measurements. “Gray Moby” was 63 1/2 feet in length, had an 11-foot lower jaw and the circumference of the head was 37 feet. Dr. Newman also made note that the lungs and stomach were filled with seaweed and mud and were probably a contributing factor to the animal’s death.

Despite the whale being dead, by the end of the weekend more than 20,000 people had arrived to see it. So many people came through the display that by Sunday afternoon Port Arthur ran out of food. Concession stands and restaurants alike had nothing to serve an ever-growing public. Emergency supplies had to be shipped in from Houston and Galveston to keep the population fed.

Daily crowds swelled to more than 20,000 per day until Wednesday, March 16 when the whale began to leak “oil” and give off a nauseating stench. The smell was so bad that the sight was declared a public health hazard and the exhibitors were forced to move the whale onto a barge in the ship channel where the display continued through the following Sunday.

During the brief display time, Port Arthur estimated that they had received more than $1 million in additional revenue from the spectators. Plummer, as the whale’s owner, received $1,000 up front plus a cut of ticket sales.

Unwilling to give up such a lucrative endeavor, Plummer refused to let a little thing like whale-sized smell and rot ruin him. Instead, he decided to take the whale on tour. After processing 326 barrels of oil from its body, Plummer had the whale skinned and shipped to a taxidermist in Harrisburg, Texas. There, 50 men worked for seven and one-half months to a tune of $5,000 to mount the animal for display.

After forming the Mammoth Whale Company with his brother Fred, Plummer set out with his whale on the powerboat Olga for a tour of every major port in the U.S.

The tour was a financial disaster. People refused to believe that the whale was genuine. Patrons accused Plummer of having the whale’s skin stretched to make it appear far bigger than it actually was. On the brink of economic ruin, the Mammoth Whale Company sold the mount to an amusement park owner from Memphis, Tennessee.

The park moved the whale to a tent by the Mississippi River for permanent display. But the display was short lived as the tent, and the mount, burned to the ground in a terrible fire only a few nights after being completed.

Note: Today, dragging a whale by the tail, tying it to a dock, gutting it, processing it for oil and having it mounted by a taxidermist is illegal.

Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today.

Great American Adventure Stories contains page-turning accounts of the Galveston Hurricane, the Alaska Gold Rush, a robbery featuring Jesse James, an eyewitness account of the Johnstown flood, and much more. For a taste of the American frontier, Daniel Boone and famed scout Kit Carson depict what they saw and experienced as the country expanded and blossomed in the West. These accounts all have one thing in common: They capture the grit and spirit of people who made America what it is today.

Created for adventure addicts there has never been a more exciting collection of stories that celebrate the indomitable spirit of the American character. Buy Now