Duncan Dobie tells of Arthur Woody, a visionary character for forest and wildlife restoration extraordinaire in the early 20th century mountain ranges of Northern GA.

The sudden spring thunderstorm stopped almost as quickly as it had started. It blew across the mountain, gray and ominous, dumping enough angry rain drops on the two of us to get our shirts thoroughly wet but we didn’t mind. The sun was soon out again and it was a beautiful spring day. Undaunted, Coach Scott and I worked our way up the small stream where we hoped to outsmart a couple of diminutive brookies. As we stalked up the ever-narrowing waterway we started seeing lots of small green caterpillars on the ground. Apparently they’d been knocked from the canopy in the treetops overhead by the heavy rain. They seemed to be everywhere. Then we watched one as it floated down the tiny stream and disappeared in a swirl. Coach Scott and I stared at each other.

“H-m-m-m,” he mused.

“That rain may have been a blessing in disguise,” I said.

We were both thinking the same thing.

“Why not?” he said with a grin.

I picked up one of the squirming caterpillars and studied it. Within minutes, we had replaced our hand-tied flies with tender green caterpillars. Thirty minutes after that, we each had caught three feisty and beautifully-colored brookies about seven or eight inches in length. We were fishing along a narrow 100-yard stretch in a small, high-mountain stream you could almost jump across.

“We’re not cheating are we…not using flies?” I asked Coach Scott, feeling a bit guilty.

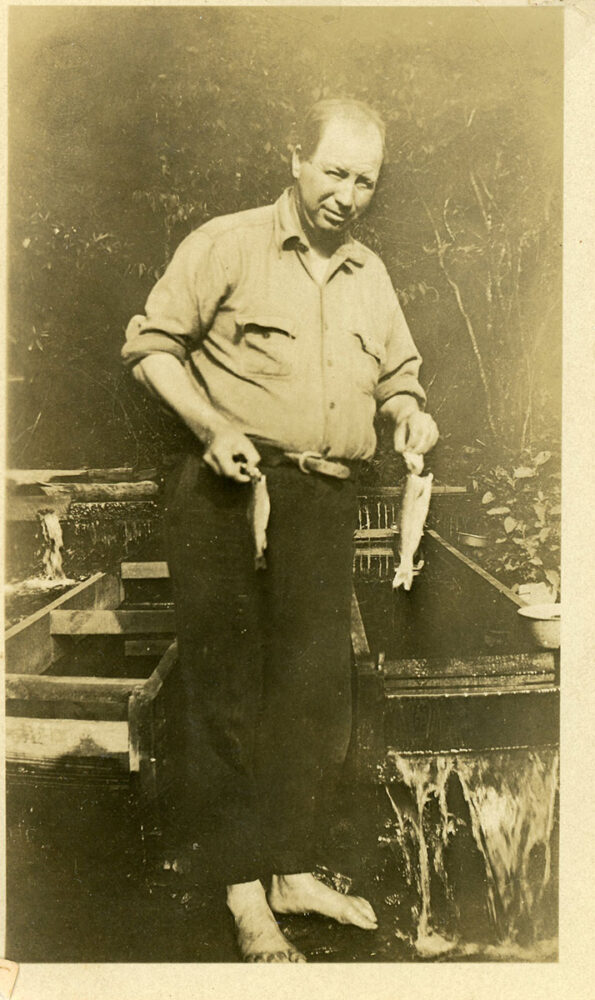

Shortly after he began his trout stocking program in 1918, Ranger Woody built several primitive trout rearing pools near Rock Creek Lake inside Rock Creek Refuge. In 1937, the U.S. Forest Service constructed a much larger and much more modern fish hatchery near the same site. Today, the 82-year-old hatchery is operated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and still going strong.

Coach Scott grinned and said, “Well, if we are, Ranger Woody probably did the same thing many a day so I expect we’re in pretty good company. After all, he likely fished this very creek more times than you can shake a stick at since we’re practically in his back yard, and I’m sure he used an occasional caterpillar or grasshopper for his beloved ‘specks’ when it seemed appropriate.”

I nodded in agreement. The year was 1964. I was seventeen years old and Coach Scott was a boyish 27. He had been my eighth grade football coach, and we’d been hunting deer, chasing grouse and fishing for trout in the North Georgia high country since I first started attending high school three years earlier. Coach Scott had not only become a special friend, he had also been the best outdoor mentor a young man could ask for and we had spent considerable time together tramping these mountains.

Funny thing, though. Each time we entered the hallowed mountains around Blue Ridge WMA, it seemed as though the legendary Ranger Arthur Woody always exerted some sort of presence. Local people talked about him all the time and he was credited with numerous conservation achievements that had a far-reaching effect on the area and the state. His influence on me was profound because of his colorful life and many accomplishments. He had served as a forest ranger in these parts from 1918 until his untimely death in 1946 at age 61. During his short tenure as one of the first forest rangers in the region, he became a living legend and left an indelible mark. I found his life to be so intriguing that I began to collect tidbits of information about him whenever I saw an article or newspaper story. Little could I imagine that some 50 years later, I would be compelled to write a 500-page book about his amazing life and legacy.

A Man After My Own Heart

The most enduring legend about Ranger Arthur Woody, and there are many, goes something like this: In 1895, an 11-year-old boy born and raised in the tiny North Georgia hamlet of Suches witnessed his father kill what was said to be the last living whitetail deer in the mountain region. Young Arthur Woody had waited all his life to reach an age where he could tag along with his father and some other local men on an exciting deer hunt. He was beside himself to be able to join these much-revered hunters and woodsmen along with their hounds on his first-ever big-game hunting adventure. But after Abe Woody killed what was said to be a fine buck, the boy’s elation turned to bitter disappointment. As the men excitedly gathered around the deer to revel in Abe’s deed, young Arthur was told by his father this was the last deer in the region.

“Take a good look at it,” Abe told his son. “Because you’re not likely to ever see another.”

How could that be the boy wondered? All his life young Arthur had heard thrilling stories about how groups of hard-working farmers and mountaineers like his father would get together when time permitted, turn the dogs lose and spend a few days chasing their favorite big game animals – whitetail deer and black bears. Arthur had wanted to be a deer hunter just like his father, and now he was being told there were no more deer to hunt. It didn’t make sense. It was a life-changing event for the impressionable young man. The catalyst to a life dedicated to forest and wildlife restoration.

Certainly the buck Abe Woody reportedly killed had to be one of the last deer ever seen in the region during the waning years of the 19th century. Later on, Arthur Woody immortalized the story by telling people he wholeheartedly believed it was the last deer ever taken in the North Georgia region. The story soon became a local folk legend, fuelled by the fact that as the young mountain boy grew older, he began to nurture a dream that he also shared with a number of people: to one day bring back the beautiful and majestic whitetail deer that had once been so plentiful in his beloved mountain paradise.

In most of the eastern states, heavy market hunting for hides and venison was responsible for the whitetail’s rapid decline during the last half of the 19th century. In the North Georgia region, however, whitetails disappeared because the early Scottish and Irish settlers depended heavily on deer for food. Using large packs of well-trained dogs and often hunting at night with fire torches, these rugged pioneers were very proficient hunters. Sadly, by 1900 when Arthur Woody was 16 years old, whitetails in the Georgia high country had gone the way of the eastern timber wolf and the once-common mountain lion.

By the time Arthur Woody was old enough to become a deer hunter, whitetails had been wiped out in the mountain region. He soon became a die-hard turkey hunter instead, always opting to use his trusty Savage 99 in lieu of a shotgun. As the turkey population declined in the mountain region, he did much to restore native birds in his beloved Rock Creek Refuge.

A Visionary Character

Most mountain boys like Arthur Woody growing up during the early 20th century were destined to follow in their father’s footsteps and try to eke out a living by farming and running a few head of cattle or hogs. But young Woody detested farm work. Having spent every spare moment of his youth hunting small game, fishing, camping, studying nature and exploring on horseback the remote mountains surrounding the small valley where he lived, the budding outdoorsman could not fathom having to plow fields and chase down renegade cattle for the rest of his life.

The late 1800s and early 1900s marked a time when heavy logging operations turned much of the once pristine southern Appalachians into vast wastelands where erosion and pollution became commonplace. Perhaps it was serendipity that offered Arthur Woody an alternative that would change his life and set him on a course with destiny. In 1912, the then-28-year-old Woody hired on with the newly-organized U. S. Forest Service to help survey the first tract of land purchased in Georgia by the federal government to be reclaimed and set aside in what would eventually become a vast national forest.

Woody had grown up hunting and fishing every corner of this 32,000-acre tract, and he knew the property intimately. Thanks to the efforts of visionary statesmen and conservationists such as former President Theodore Roosevelt, who was one of the driving forces in seeing that laws were passed by congress to appropriate money to reclaim the clear-cut and devastated forestlands in the southern Appalachians, the restoration of these once pristine woodlands became a reality. Because of his father’s adamant dislike and distrust of anything having to do with the government, Arthur Woody was nearly disowned when he happily accepted the “government” job.

In many ways, it was a match made in heaven for the eager young woodsman, although he was very much an individual and often ignored orders. That fierce independence did cause a few problems along the way, but the Forest Service quickly realized the value of this visionary thinker and Woody quickly worked his way up through Forest Service ranks. In 1918, he became Georgia’s second official forest ranger. As the Forest Service continued acquiring land throughout the 1920s and ’30s, his ranger district eventually grew to be one of the largest in the nation, encompassing more than 200,000 acres by 1940. The sciences of forestry and wildlife management were still in their infancy in 1918, but Woody took the bull by the horns and plowed full steam ahead with many farsighted innovations.

From his first day on the job, his vision for his district went far beyond the noteworthy task of growing trees and protecting the forests. Even though the fledgling Forest Service lacked the resources to delve into other areas of conservation – namely restoring fish and wildlife populations that had also been greatly diminished – the determined ranger quickly took matters into his own hands. “Do what needs to be done and ask permission later,” became Woody’s modus operandi in dealing with his employer.

Although he never went beyond the fifth grade, Woody was a highly intelligent and motivated individual who had a knack for solving problems using good old-fashioned “horse sense.” Even though he refused to wear a uniform except on the most formal occasions and he was known to disregarded government red tape and Forest Service protocol altogether, his “seat-of-the-pants” methods and solutions often worked much better than those of the so-called “experts.” His stubborn ways may have raised a few eyebrows with his superiors from time to time, but they seldom complained. Here was a man who got things done!

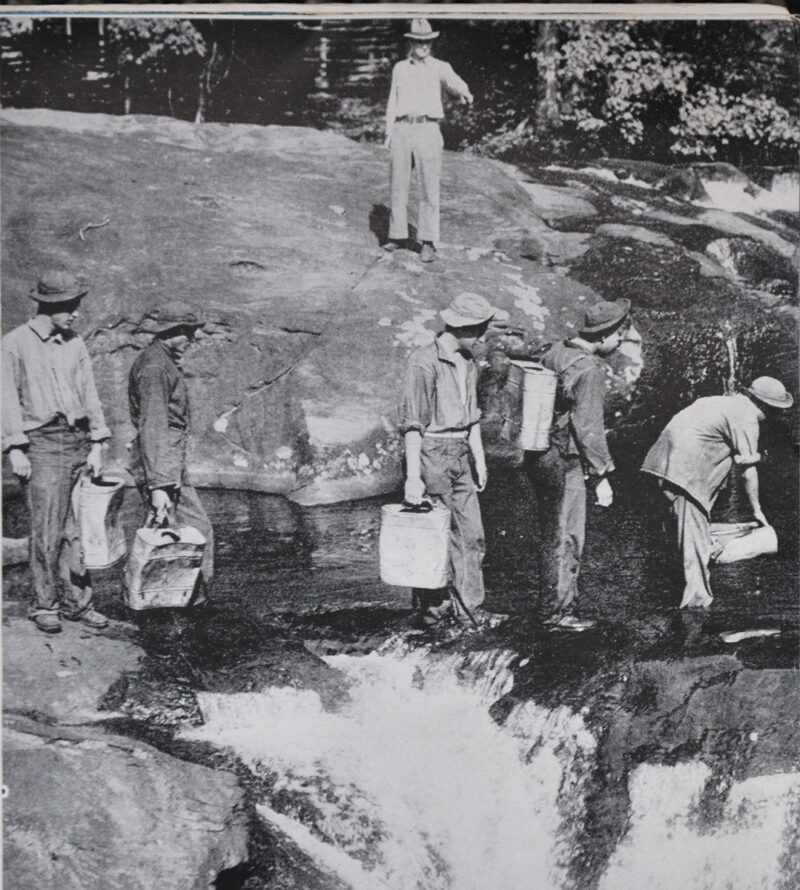

With the advent of the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1933, sometimes known as “Roosevelt’s Tree Army,” Ranger Woody had a ready and willing force of able-bodied young men who carried out many of his conservation initiatives. Here the CCC boys are stocking trout in a remote mountain stream.

Woody literally “set the woods on fire” with innovations and improved ways for growing trees and protecting the young forests. Throughout the decades of the 1920s and ’30s, he built at least three flood control lakes, three fire towers and, using crushed gravel from a quarry on his own land, he improved miles of impassable mountain roads that previously turned into mud bogs during the rainy months of winter. With the formation of the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1933, Woody formed a strong partnership with at least three of the local CCC camps in his area.

Suddenly Woody had a ready-and-willing work force of hundreds of able-bodied young men who grew to idolize him and would do anything he asked of them. No job was too great. From 1933 to 1941, when the CCC was forced to disband because of World War II, these dedicated young men helped Woody and the Forest Service achieve dozens of crucial projects: planting trees, fighting forest fires, running miles of telephone cable across the mountains, building several state parks, stocking fish in remote areas, building and improving roads, building fire towers and lakes; the list goes on and on.

Had he lived another decade or two beyond 1919, Theodore Roosevelt no doubt would have been proud of the backwoods forest ranger his U.S. Forest Service had recruited. In many ways, Woody and Roosevelt were cut from the same cloth. They were both visionary and they would stop at nothing to see an important task completed.

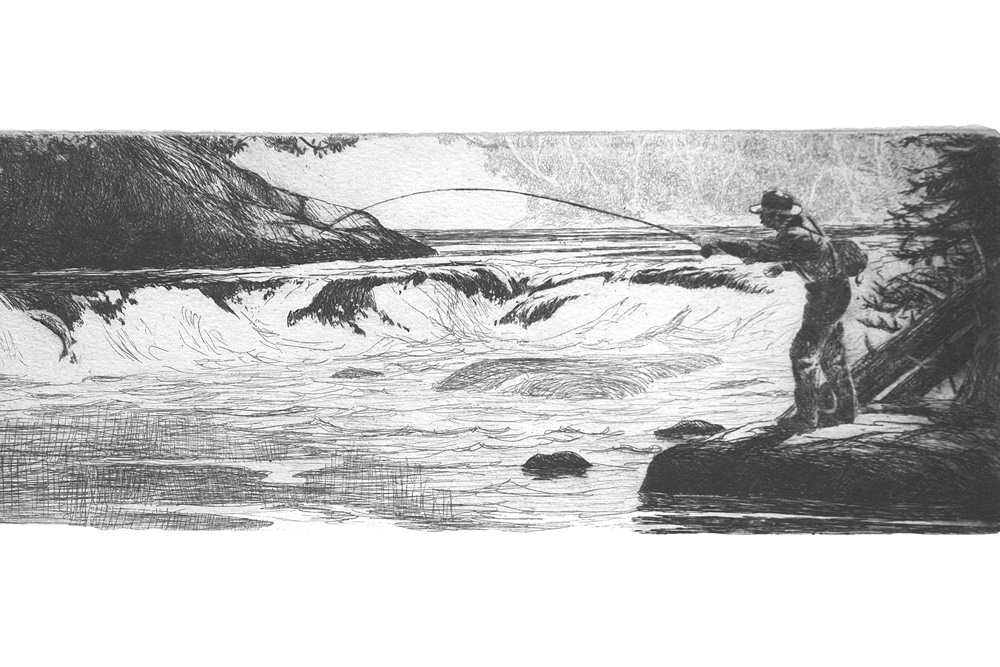

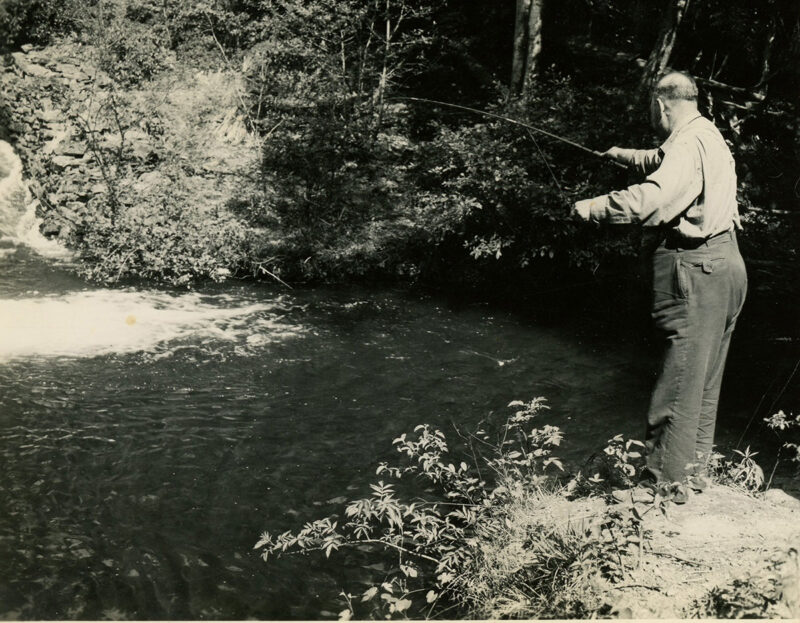

All his life, Arthur Woody love fishing for the diminutive native brook trout he always referred to as “specks.” “I know most of the trout by name,” he often said. “If I’m lucky, I’ll get one on a hook.” He did much to restore the imperiled species during the first half of the 20th century.

The Right Man for the Right Job

After becoming a full-fledged forest ranger in 1918, Woody wasted little time in implementing several important initiatives that went far beyond the bounds of his job description. In 1918, he began stocking non-native rainbow and brown trout (purchased out West) in some of the nearby streams and rivers he had fished as a boy. In addition, having grown up fishing for the native brook trout he fondly referred to as “specks,” he also began restoring the badly depleted brook trout population in his area by building several fish pools and raising fingerlings from eggs. As with the deer that had totally disappeared, brook trout numbers had dropped drastically in the early 20th century as a result of being over-fished by locals and the abusive logging operations that polluted streams and filled them with silt.

By 1927, Woody had done well buying and selling land. He had been heavily involved in helping the Forest Service acquire land since 1912, and over the years he began to buy small tracts the Forest Service did not want. This success gave him a certain amount of financial security beyond his Forest Service paycheck and he was about to embark on one of the greatest adventures of his life. He was going headlong into the deer-raising business!

Ranger Woody (pictured on far right) began his very successful deer stocking program in 1927 with the purchase of five young fawns from the Pisgah Game Reserve in North Carolina. Thirteen years later in 1940, the herd had multiplied to an estimated 2,000 animals. Despite Ranger Woody’s strong objections, the first legal mountain deer hunt in modern times was jointly conducted by the U.S. Forest Service and the Georgia Game and Fish Department in November 1940. Twenty-two exceptional bucks were taken.

Over the years, Ranger Woody might have stolen a rare glimpse of a surviving deer from time to time during his extensive wanderings across the mountains, but whitetails had been absent from the mountain region during most of his life. In the summer of 1927, he drove to the Pisgah National Game Preserve in western North Carolina. He purchased five young fawns for $100 and took them home. He built a pen next to house to protect the young deer from dogs and bottle-fed them until they were old enough to eat on their own. These five deer became the foundation for an expanding deer herd that within a few years would once again thrive across the North Georgia Mountains.

When the fawns were about a year old, they were released inside Rock Creek Refuge (later to become Georgia’s first wildlife management area, the Blue Ridge WMA. This land was part of the original tract the Forest Service purchased in Georgia in 1912. For years, Woody had urged the Forest Service to make this tract a wildlife reserve. It finally happened in 1936.)

Once they were free-roaming, Ranger Woody let it be known to one and all that there would be a steep price to pay if anything happened to any of his deer. Over the next few years, he continued buying deer from the Pisgah Reserve and releasing them in the refuge and surrounding areas. By 1940, from a seed stock of no more than 70 original deer, the thriving herd had multiplied to an estimated 2,000 animals.

A beaming Ranger Woody poses for the camera with a longbow during the historic archery hunt at Blue Ridge WMA in October 1940. Thirty bowhunters from nine states including the noted Ben Pearson participated in the highly publicized hunt. The Ranger correctly predicted that “nary a hair’ll be shaved off” any of his precious deer by the rookie bowhunters. He was right!

Throughout the 1920s and ’30s sportsmen had been catching trout in Ranger Woody’s district “as long as your arm.” Because the deer herd was also thriving, many of these same sportsmen began to petition the state and the Forest Service to allow some sort of legal deer hunt. In the fall of 1940, much to the chagrin of Ranger Woody, the first legal deer hunt of modern times was held inside the refuge. Twenty-two bucks were taken by ecstatic hunters. Many had exceptional trophy racks. Since Ranger Woody had never hunted deer as a boy, the deer in the refuge had become sacrosanct to him. He was adamantly against any type of hunt. But the tough old mountain man had to relinquish his inner feelings. Outwardly he praised the hunters as they brought their trophies into the check station. Inwardly he was greatly saddened because he had raised many of the bucks from fawns.

Woody suffered a stroke in 1944. His health rapidly declined during the following months. He died in June 1946, having left behind a vast legacy of conservation and humanitarian achievements unparalleled in Georgia history. Several years after his death, he became widely known as the “Barefoot Ranger of Suches.” No one knows how the nickname originated, although he was known to take off his boots occasionally so he could feel the rich mountain soil between his toes.

Arthur Woody was a larger-than-life character whose fame grew to legendary proportions during his lifetime. Today, some 74 years after his death, his life’s work still impacts the rugged mountains from which he was spawned. One of his favorite sayings was, “I make a thousand dollars a day – in scenery.”

As a youngster hunting and fishing the same mountains and streams that Arthur Woody had frequented and protected decades earlier, his life and legacy somehow grabbed me and wouldn’t let go. In 2016, my dream about writing a book on his life and times became a reality. Today, whenever a trout rises, whenever a deer crashes through a laurel thicket, whenever a breeze sifts through the tall white pines where gobblers like to roost, I sense the smiling ghost of Arthur Woody is close hand. His spirit will always be part of those sacred mountains. Truly he was the last of the old-time forest rangers.