I was not lucky enough to have known my great-grandfather, Theodore Roosevelt. When I was a child I would fantasize about spending time with him. It was only many years later that I realized I had indeed gotten to experience him, albeit in a curious way.

Much of my childhood was with my grandfather Archie, TR’s next-to-youngest child. He taught me about birds, which he greatly loved, particularly untangling the “confusing” fall warblers; he gave me my first gun, a Remington .22; he taught me to shoot skeet using a .410 and a rusty old sling-shot affair to throw the clays; he took he took me on my first hunt, for deer in the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania; and just before I went to Harvard he arranged for me to spend an unforgettable summer working in New Mexico at Carson National Forest, where the chief ranger was a man named Proctor who was mostly of Apache origin, and who had served with my grandfather in New Guinea during World War II as one of the famous code-talkers.

Grandfather would often take me and my little friends camping in the wilder parts of eastern Long Island with its southern barrier of sandbars. There, we would spend a wondrous couple of days living off what we could gather or catch, and being scared half to death by Grandfather who told the most terrifying ghost stories around the campfire.

It was not until many years later, when I read more about TR, that I realized my grandfather was re-enacting his childhood spent with his father. I consider myself a lucky man.

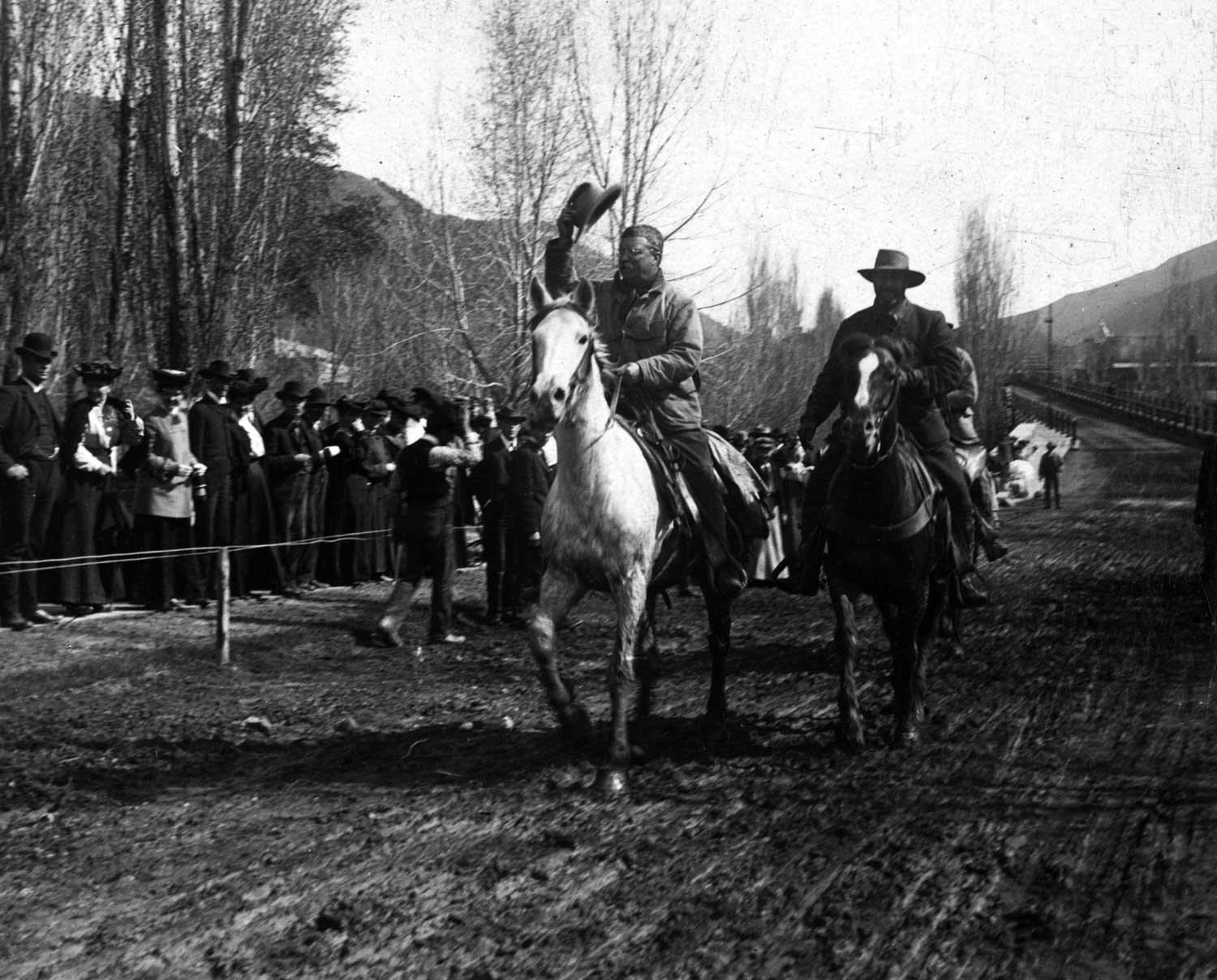

Theodore Roosevelt loved the outdoors and spent every minute he could outside, whether a short hike at Rock Creek or months in the wilds of the Amazon jungle or on the African savannah. He truly enjoyed camping or staying in primitive huts. Even during his time as President he would occasionally weekend in Virginia at Pine Knot, a four-room sharecropper’s shack that he purchased as a getaway with his wife Edith. It had neither electricity nor running water. A more humble presidential abode cannot be imagined.

But what he loved most was living outdoors, often with only a blanket and some salt and coffee, providing for himself off the land and sleeping under the stars – or if necessary, in heavy rain! I have calculated that during his entire adult life he spent an average of one month a year living under canvas. That claim could be made by very few, if any, presidents before him and certainly none since.

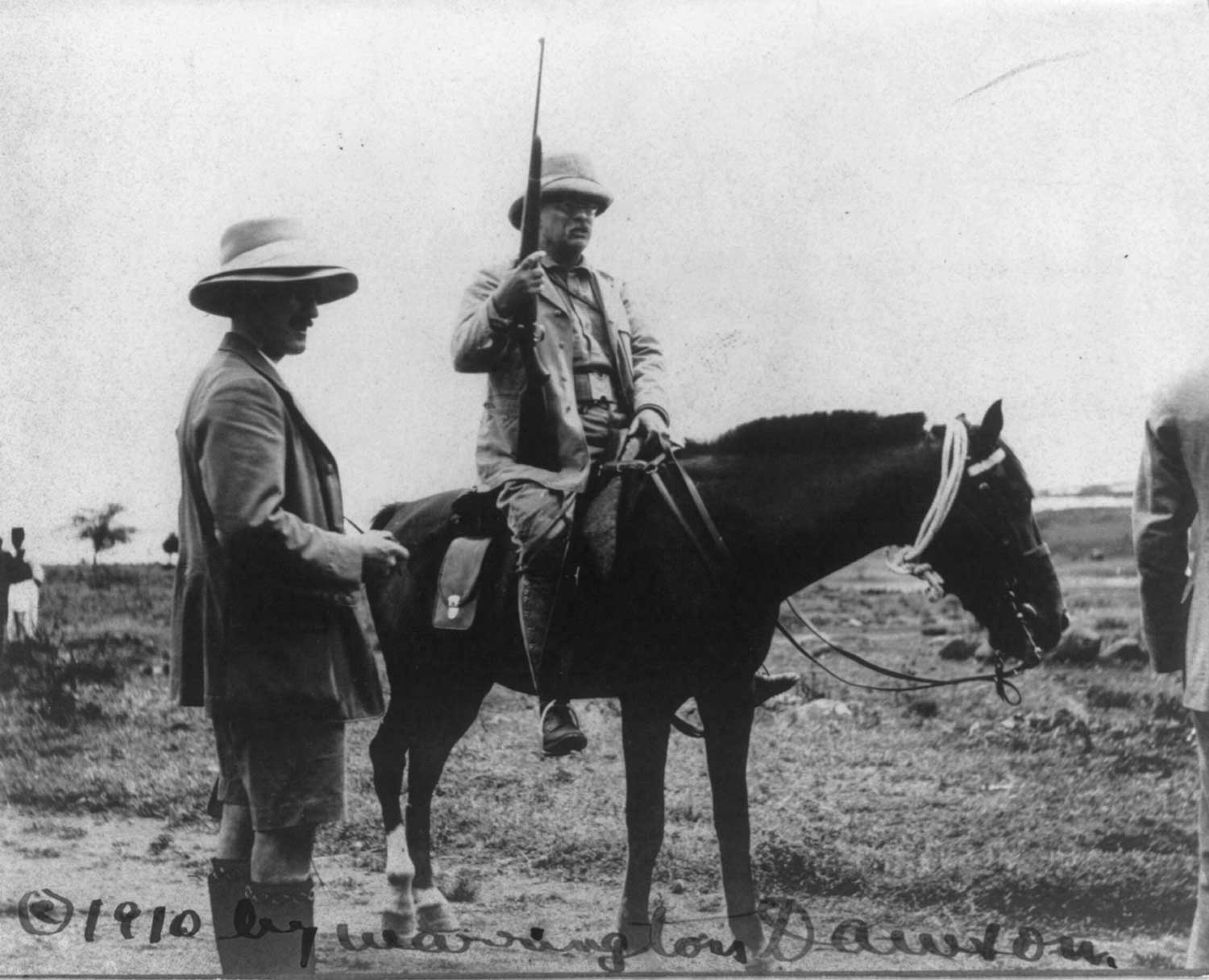

TR stands proudly with his Holland & Holland double rifle after killing this black rhino on his months-long safari that involved hundreds of native helpers. With him is Captain Slatter, owner of an ostrich farm at the foot of Kilimakiu Mountain where TR hunted a variety of game.

He loved all aspects of the outdoors, especially the animal life. First it was birds and small animals. Later it was the bigger beasts. He loved to hunt them, but he also loved them for the magnificent window they opened on the natural world.

Today, it seems inexplicable to many that a hunter could be both a conservationist and claim to love the animals he pursues. This lack of understanding comes mostly from ignorance. From time immemorial hunters have studied, respected and loved the animals they hunted. This was certainly true of TR, whose careful observation of the large mammals of North America made him a widely recognized expert on their lives and habits.

There is a story that once while he was President, the Smithsonian Institution received the unlabeled embryo of some species of deer, which the experts were unable to identify. An argument ensued, with the majority of scientists favoring a certain species. Someone suggested that it be sent over to the White House for the President’s opinion. It was returned with a note identifying it as a completely different species. Later, it was determined that the scientists had been wrong and the President had been right.

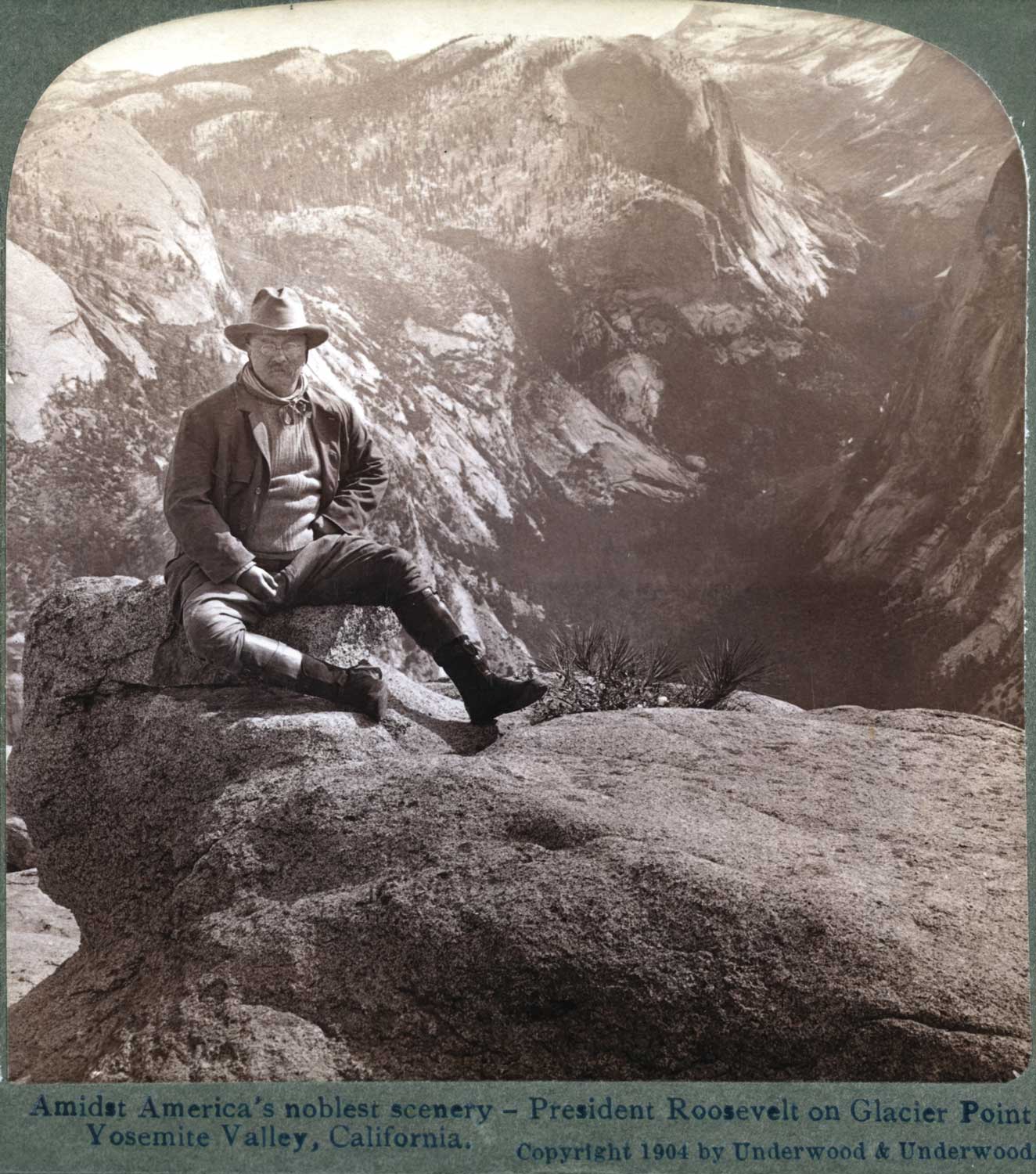

Not only was TR a close observer of wildlife, he was one of the leading conservationists of all time. Books have been written on this subject, so here it will suffice only to mention that he was a founder of the first influential private conservation organization, the Boone and Crocket Club, and that he was the greatest conservationist of all the American presidents.

During his years in the White House, TR conserved some 230 million acres of land, an almost incomprehensibly large number. It amounts to about one-seventh of the entire landmass of the Lower 48 states. Or, looked at another way, it represents about 84,000 acres for each and every day of his presidency.

Theodore Roosevelt was, of course, an extremely intelligent, perceptive and resourceful man who had an uncanny ability to bring his hopes and goals to fruition. But TR had many other talents as well.

The disastrous winter of 1886-1887 destroyed the cattle business on the northern plains where TR had his ranch and took with it a large portion of his inherited wealth. To support his growing family he needed to find a way to make up the loss. For most of his life this would be through his pen.

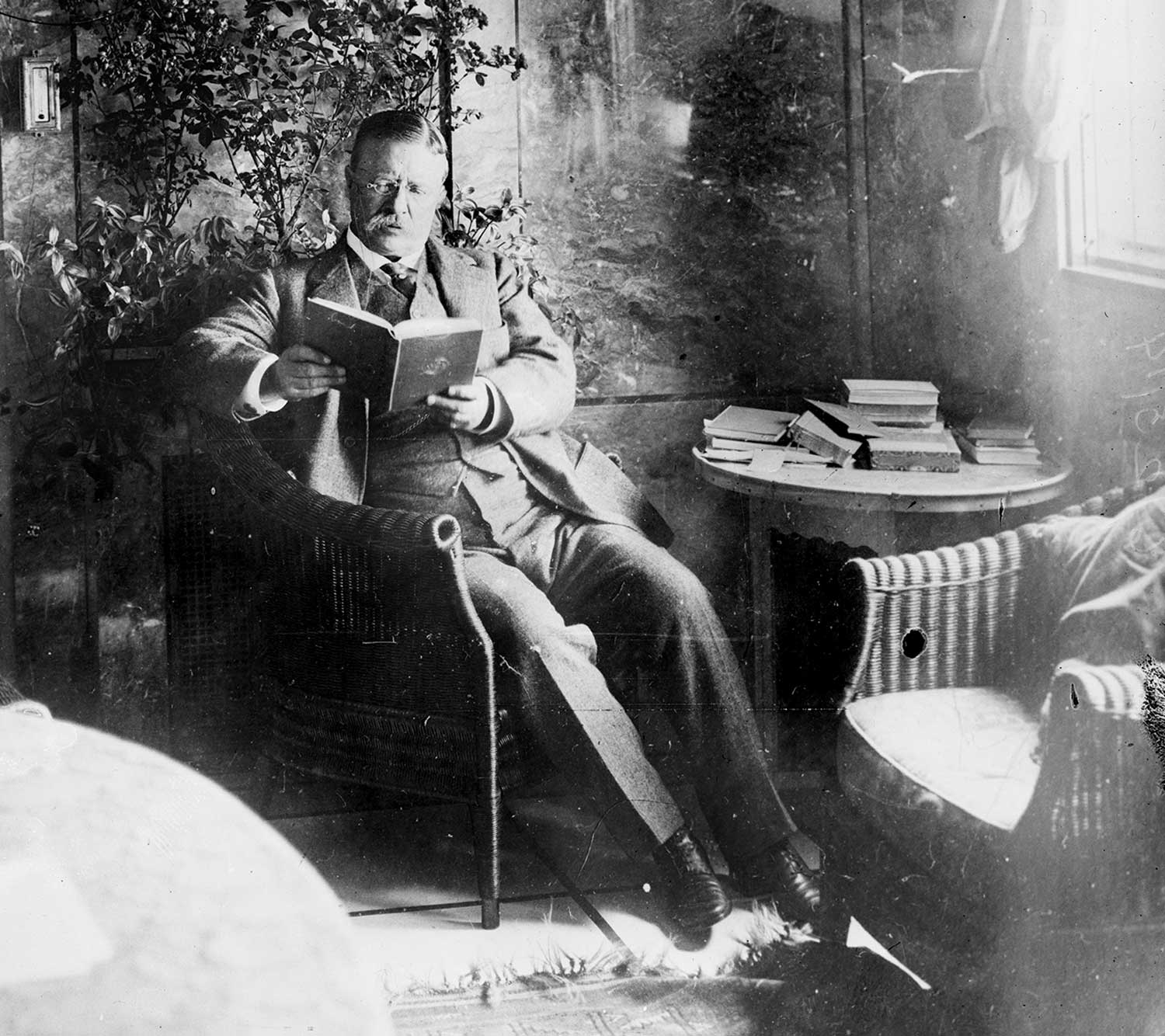

TR ultimately wrote 35 books, hundreds of articles, dozens of book introductions and an estimated 150,000 letters. His best and most successful books were his adventure stories, including his days out West, his Spanish-American War experience, and his trips to Africa and the Amazon. He also wrote biographies, histories and his own autobiography. Some of these are still in print today. In addition, for much of his life he was a paid columnist for a number of publications. In fact, TR never used a ghostwriter, even for his speeches as President.

TR was a disciplined writer, although he said it did not come easily to him. Each day on his long African safari the exhausted hunters would return to camp where they would do little more than rest and eat dinner. But TR sat down at his makeshift desk and, in triplicate, wrote chapter after chapter of what would become his best-selling book, African Game Trails. He kept one copy of each chapter and sent the other two to Scribner’s, his publisher, by runners, one north up the Nile and the other east to Mombasa. Amazingly, every page reached New York.

With hardly any editing, his stories were published, first serially in Scribners’ magazine and then in the book, which was released before TR returned to the U.S.

He repeated this taxing routine on his Amazon adventure, but under even more difficult conditions. His camp was much more primitive, the insects were fiercer, and he became extremely ill, even at times close to death. Nonetheless, he soldiered on and completed the text by the time he got back to Sagamore Hill.

In TR’s day, photography was still in its infancy. Most of the pictures of Roosevelt are either studio portraits or news photos of his political life. We do have a few images of his outdoor life, but they are mostly grainy shots that by today’s standards are unsatisfactory.

For those who are aware of TR’s extraordinary range of interests, it will be no surprise that he was also a photographer. He owned what he called a Kodak, what was later referred to as a Brownie, the Model T of cameras. He developed his own images and even had a makeshift darkroom dug out under his North Dakota cabin. It is unfortunate that few, if any, of these images survive.

TR could draw, although not very well. His journals are filled with sketches, as are his famous picture letters to his children. However, he had enough sense to commission professional artists to illustrate his books, most famously Frederic Remington. These artists’ illustrations are excellent, but one wishes for more.

Sleep Walkers – oil on canvas, 32” x 52” by John Seerey-Lester.

I was careful to show a southern hemisphere sky in this painting. The elephants were sketched on location in the Maasai Mara of Kenya.

We are fortunate that John Seerey-Lester, whose spectacular paintings are presented in his book The Legendary Hunts of Theodore Roosevelt, so often chooses TR as his subject. John has an extraordinary ability to bring to life the high drama of the hunt. TR, of course, could supply him with an almost unending series of opportunities to display his artistry.

John Seerey-Lester has featured several of TR’s hunts to portray in his books. Naturally, his African safari is here. The climax of a lion hunt provides the requisite drama, and the author tells the story well. The result of the hunt could easily have been the fulfillment of the publicly expressed hope of one of TR’s political rivals, who told a reporter as TR was leaving for Africa that he hoped “the lions would do their duty.”

This is only one of many occasions when Roosevelt’s life depended on his coolness under pressure. It was this, and not his shooting ability, that saved the day. TR, who by the time he went to Africa was blind in one eye and had very poor vision in the other, was once asked if he was a good shot. He responded, “No, . . . but I shoot often.”

He certainly did in Africa and, as was his habit, recorded every shot in his journal.

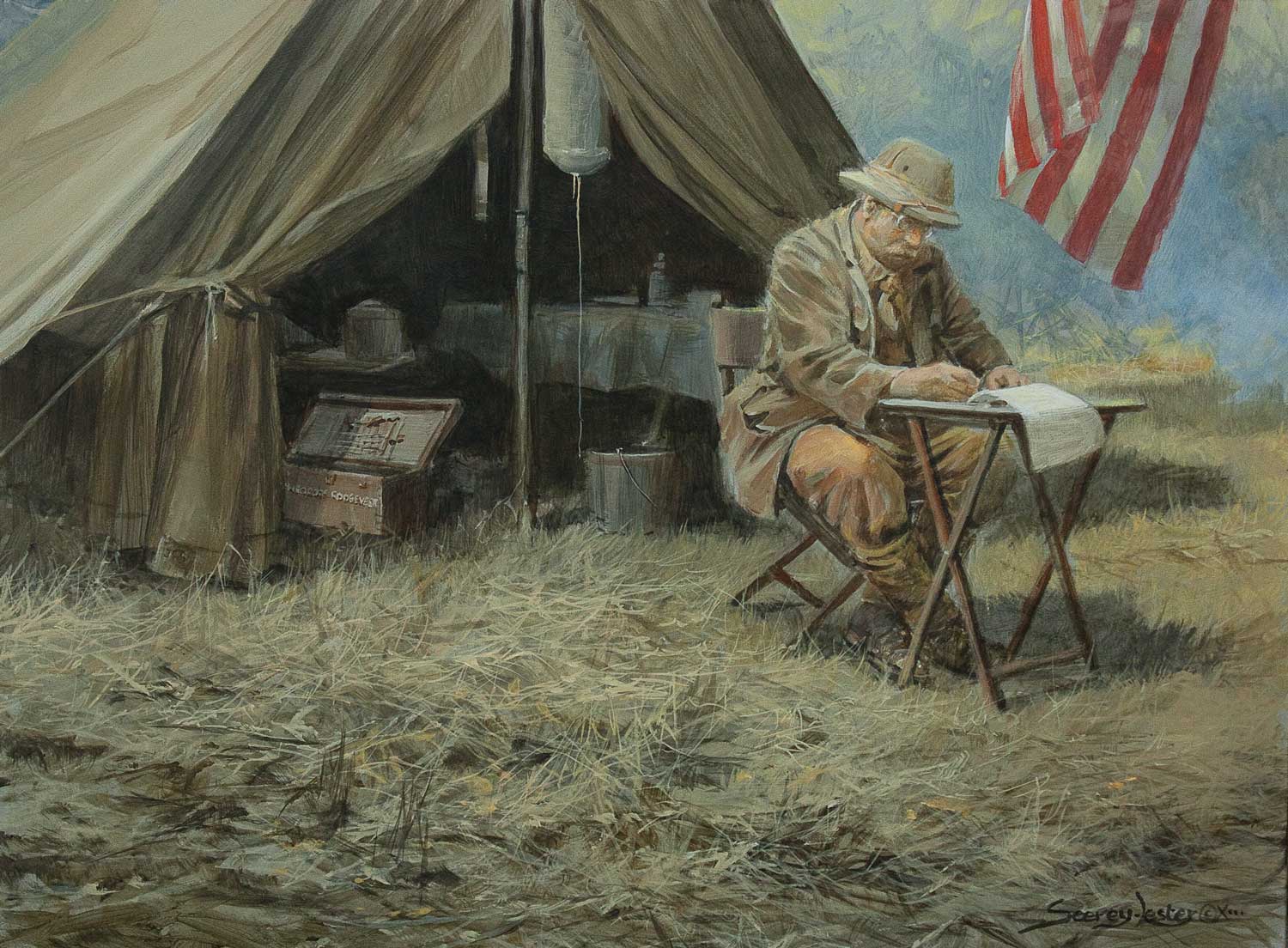

Safari Writings – acrylic on panel, 12” x 16” by John Seerey-Lester

In this painting TR is writing while on safari for his book, African Game Trails. He wrote in triplicate, keeping one copy for himself and sending two to his publisher in America, one via the Nile, the other through Mombasa. Amazingly, everything eventually arrived in New York, and the book was published in 1910, ahead of his return from Africa.

Another of TR’s hunts Seerey-Lester has chosen to depict is one of my favorites. Roosevelt was a young and mostly unknown man who had heard rumors of a white goat that allegedly lived in the very highest reaches of the remote and almost inaccessible mountains on the Idaho-Montana border. Many biologists believed that this animal was merely a myth and did not exist. But TR had seen one, or at least what was left of one.

As chance would have it, one of the very few taxidermists in that part of the country was in Medora, the town in North Dakota near TR’s ranch, and he had been given the assignment of mounting one of the very first white goats ever shot. This fired TR’s ambition to hunt them.

TR’s Quest for Mountain Goat – acrylic on panel, 16” x 12” by John Seerey-Lester.

John posed his son, John II, as TR and Chuck Snyder as Willis, on a golf course in Florida, as there was no handy mountain range.

No other animal in the Americas is more difficult to hunt and none live in a more formidable and beautiful habitat. TR learned of hunter Jack Willis, who lived in Montana and might be willing to guide him. Rumor had it that he happened to be planning a trip into the mountains.

TR wrote Willis a letter that was returned with a scribbled note disparaging TR’s penmanship and refusing to guide him. It will not surprise you to learn that Roosevelt was not so easily put off. He caught the next train to Montana and continued to pester Willis. Money didn’t work, as TR’s offer to pay for the whole expedition didn’t win over Willis. But persistence did, at least partially.

Willis probably realized that the only way to stop TR’s pestering was to tell him he could tag along, and be permitted to follow at a distance, completely on his own, with Willis taking no responsibility for him. Most likely he hoped that TR would abandon the trip after a few difficult days. If so, he greatly misjudged the young hunter’s persistence.

John’s brilliant paintings allow the modern hunter to relive some of TR’s greatest hunts and those of many other legendary explorers and hunters.

Note: This article originally appeared in the 2013 Guns & Hunting issue of Sporting Classics magazine.

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now