In the 89th year of his being, Ben Willow had died where most completely he had lived, upon the hills of home, with a dog and a gun.

A little less than midway through this book, iron-willed old Missouri-West Virginian Ben Willow throws himself mercilessly once more against Seven Step Mountain. It is his to do, as surely as the sand must meet the sea. He seeks its summit, as he has all others of his life, by conviction, and never conciliation.

Clyde Wood, his oldest and dearest friend, will say it best in a later chapter.

“Ben Willow was a passionate man. He lived that way and he died that way. He had strong notions ’bout most everything … especially in his latter years, and most of all about eternity. Where he would spend it, and how he would get there. He agonized over it toward the end, and when he decided how it must be, he found himself torn unmercifully between the two greatest loves of his life.”

But Ben’s death on the Mountain brings an ordeal to those whose task it has been to love him. A trial that will ask of each all they can give. Most of all, Jenny. Through their triumph shines the incredible courage of a dog, the loyalty only true friendship can bestow, and the eternal circle of a sporting life.

There’s a bit of Ben Willow in all of us who hunt passionately, who spend ourselves relentlessly and without shrinking to earn the incomparable gifts of the out-of-doors. My heartfelt wish is that it rings true in the pages of Jenny Willow. —Mike Gaddis

It was grand … being here. Being back. Being alive. Far below, over the winding river of the valley, a skein of geese pulled through the sky, keeonking glad tidings to the new morning. He could see their extended wedge against the darker valley floor, stretching and closing, drifting alternately in and out of the mist through filtered sunlight. He could feel his spirit peaking, soaring with release. He was as wild as anyone of them. High and free again. He looked at the prancing setter beside him, wired with exhilaration.

“Awright, Jenny girl, unkiver us a grouse.”

He hit the whistle lightly, thrilling as she tore away. Powering to the front, she layed forward out of sight, then flashed white against the distant laurel for a second as she whipped right up the hillside.

He followed slowly, conserving himself, estimating his strength against the day ahead.

Five minutes later, she remembered who she was hunting for and closed to Ben Willow range, falling into pattern. Quartering comfortably, opening biddably when the opportunity arose, she made for the old homeplace clearing at the height of the slope. Where she had pointed in her maiden season, when first he had carried the gun.

“Find ‘im Jenny,” he called, blowing a roll-out whir on the whistle. He caught himself. The last thing an old man needed to do with a dog of Jenny’s ambition was to hit a whistle. It was habit, ingrained for fifty years. The setter accepted it with a caveat.

Ten minutes afterward, Jenny was pointed. He heard the beeper trip. He was a while getting there. She was standing almost where she had that first day, pledged decisively just inside the woodsline. Two birds went out before he was set, slightly apart, light and left. Jenny watched them up, swelling onto her toes. He lost the first as it leveled low among the trees, then caught the second off his left shoulder as it topped its upward spiral and banked for the clearing. It fell cleanly to his single shot. He could hear its death flutter as he released the setter for the retrieve.

Delivering to hand a prim little hen, Jenny accepted thanks, shook herself and rolled in the leaves.

Sent on, in censed with desire, she clicked ahead.

Birds were astir. Less than an hour into the hunt, she had her second find. He watched as she went birdy on the hillside above, the quickening pulse of her tail, the tautness of her quest. Boldly cautious, she hastened forward, unraveling the warm, lingering spoor. Baffled momentarily, she corrected, stitching back and forth, working the breeze for a cue. It reached her nose, snapping her Sideways. Throwing her head high, weaving her way into the scent, she feathered steadily through broken fingers of laurel. Twice she stiffened, then roaded ahead. The bird was running.

Ben was moving now, hurrying ahead, trying as he would have in olden days to circle wide, get in front of the bird, place himself for the shot. He was ill-equipped to do it now, but he was trying, stumbling as he picked his way and hying to keep an eye on his dog at the same time.

She had stopped again, lofty and riveted. He adjusted, cutting in slightly. Now, once more, she was moving, mincing forward on cat paws. He had closed the distance. He was almost abreast of her, though 40 yards below. She halted again, solidly mid-step, a forepaw afraid to gamble the ground. She was 12 o’clock high, blazing with intensity.

“A’right, Jenny,” he acknowledged softly, “I’m up.”

Up, but laboring for breath and less than easy on his feet. Ben Willow was off-step and astraddle a small log when the laurel 130 yards ahead and the shadow of the grouse exploded through a confusion of bottle green leaves, caught a pocket of light and burned russet and gold for a split instant. Purely of reflex he whirled, twisting from the hip. His arms swept upward from his chest and the Parker leaped to shoulder in the same moment hat his cheek found the stock It settled for less than a second, before pulling him off balance, at the very limit of his lateral axis. In that instant, the muzzles gained the silhouette of the speeding bird, and he pulled!

The shot thudded against his shoulder and the hillside, reverberated into the hollow. As a Single pellet from the chilled load of Federal 71/2S found its mark Faltering, disoriented, the bird pulled vertically skyward, higher and higher. Toweling, it battled gravity for a suspended moment .. . wings beating furiously … then toppled.

He watched, touched by remorse, as the grouse fought to survive and lost. It was an awesome thing, a head-shot bird.

He clucked to Jenny. She had marked the flight and was on the bird in an instant, returning full of prance.

“Show-off,” he said as he took her offering, a large cock. The perfect compliment to a fine, mixed brace.

The little setter shook Vigorously.

“Jen-n-ey, good girl!,” he praised, pulling her against his leg and patting her side soundly.

He glanced upward. “Hey, Whadaya think o’ that, Tony?

“Nice piece of grouse doin’s.”

Wasn’t bad himself.

“Pritty tight, old man,” he sang out loud.

He chided himself for being boastful, but even a spurred rooster found the gall to crow. When the younger cocks of the walk wore him glum, and suddenly he cornered a loose hen.

He turned the bird to its back in his hand and smoothed the breast feathers, then nudged it into his vest. How many grouse had he stuffed into that old vest? He wished he could go back and count, day by day, dog by dog.

It was eventuating into a sterling morning. Young still, with birds at the cleft of his back, two already, probably the third if his shooting held. An hour or so more and they could laze in the meadow, chew a sandwich, and watch the clouds by. Relive each flush and feather.

Jenny was already ahead, quartering the draw. He pushed on.

Not 30 minutes later, she was pointed again in a small damp hollow. A woodcock tittered away. Ben leaned into the rise and then dropped the gun slowly back to port, his face lightening. “Another time,” he vouched. Today, it was grouse.

Onward and upward.

Two hundred yards on, another grouse went out. Blowing from the hollow below and crossing the next ridge. Jenny was no-fault on the opposite slope. He watched it away.

Detouring around a dense wall of rhododendron, he climbed on. Slightly perturbed.

His strength was waning, and it annoyed him.

He had crosscut the grade with every opportunity, but still his splindly old legs were beginning to ache with the ascent. His lungs were pumping, harder it seemed than they should, and his heart was thumping. Resigned, he pulled up to rest, parking on a stump. He sat the butt of his gun on a knee, cradling the barrels in the crook of his arm, while he caught his breath and patiently picked loose the wrapper from a piece of hard candy. Cherry. The flavor burst sweet against his tongue.

Overhead, a militia of crows was giving a big redtail how-for. From a secret hollow, a woodhen joined the din, drubbing a crescendo on a hollow bunk, then shrieking devilishly at the deed.

Jenny clipped back to check on him. Her eyes warmed as she neared. Hushing up, she laid her ears back and pushed her head between his knees.

“What say, Jenny girl. No grouses locally?

“Bet ya a scrambled egg in th’ mornin’ they’ll be one on the ridge.”

The hardest climb of the journey lay just ahead, up the steep rocky slope and the sliding shale to the cap of the mountain and the winding spine of the ridge, which he would ever mark by that first climactic day with Trip and Cindy. The ridge which guarded the hollow, where the tiny stream that watered Sam Thomas’ meadow grew from the rocks, and first whispered the lesson of the stone.

Jenny studied him briefly, looking earnestly into his eyes.

Only a dog, he thought.

He tousled an ear. What a Godsends he had been.

He pulled out a couple of Kraft Singles he’d brought for her, tearing off slices and doling them one-by-one to stretch it out. She was silly over Kraft cheese. And spaghetti.

Cheese downed, she dropped and wallowed, running her muzzle under the leaves and snorting. Then she lay flat on her side, cutting her eyes up at him, beating the ground with her tail.

“Flirt.”

She wagged the harder.

Up suddenly, she shook nose to tail tip, ready to go again.

“Alright, you’re the leader. Just remember the old jay whacker who’s doin’ the followin’.”

Jenny bounded away, upward, the muscles knotting as her hind-quarters bunched and pumped against the incline.

He extended both legs and flexed, stretching the muscles until they burned mildly, then dropped them and pumped each once in turn. Standing, he located the Pepsi among the grouse in his game bag, uncapped it and downed a brief swallow.

He could see the broad, mottled face of the slope looking down on him through the notch of the saddle above…massive and imposing, its great hulk dwarfing the lesser hill between. Black-green veins of rhododendron wandered its wrinkles like a congress of gypsy tribes, trailing around and between the staggered, gray monoliths of rock. Vaguely, under the timbered skyline along its summit, he could discern the long backbone of the ridge. He wished he were there.

He wiped his mustache casually with his sleeve.

He could bear due east, skirt the mountain and catch the bench. Come into the meadow from below. It would avoid the arduous grind to the ridge. But Jenny was already en route there, and there lay the pinnacle of the challenge …and the birds … for they loved the head of the hollow and the warm sun and green thickets and blowdowns of the ridge. He had never taken the easy way to any destination. It was not Ben Willow.

He wanted to come to the stream and meadow as he had that first day, and each time since, have it unfold before him as he remembered it. To feel again at least a semblance of discovery. To earn the privilege of it, by conviction, not compromise.

He gathered his resolve and started after his dog.

Negotiating his way up the remainder of the hillside to the saddle, he reached the monumental old growth spruce that paralleled the seventh bench. He paused for only a moment, laying his hand reverently upon it and craning upward to its staggering zenith, then dropped into the nan-ow draw beyond. Jenny showed several times, sweeping nine-to-three, going birdy once in the salad greens that floored the draw, but making nothing of it and hunting on. He rested shortly, watching her away once more, enjoying the grace of her going and obliging momentarily the spell of indigestion at the pit of his chest.

“Bird in here, Jenny … wasch clo-s-s.” The encouragement came almost involuntarily.

Conserving himself as he pushed along, he accommodated the small headland that stepped to the great slope. It towered ahead now, like a biblical Goliath.

He had lost Jenny temporarily, but now he had her again, already well above him on the soaring hillside, cutting the grain, questioning the clot of grapevines bordering an expanse of laurel.

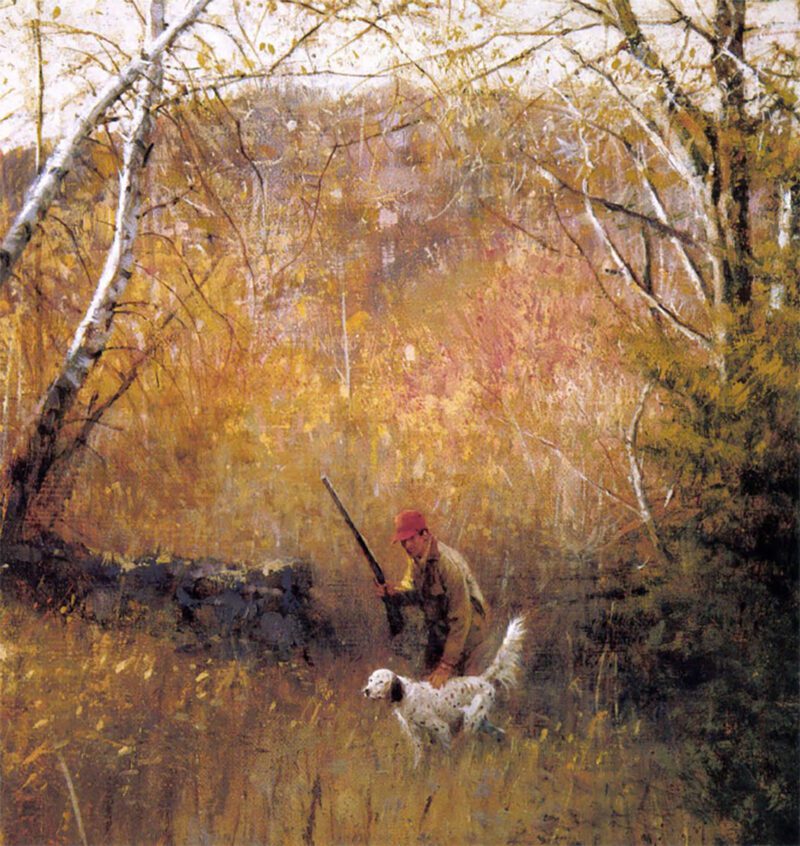

Steadying the Pup by Bob Abbett

Steeling himself, he started upward, step over step, thigh over thigh. He jacked himself up the merciless incline until his withered legs burned and his calves threatened to cramp. Up and up, until his breath grew congested and dragged. Reaching the quarter-mark, he sidetracked 30 feet to reapportion his ascent past a large jut of rock. He paused to breathe and glanced upward again, throwing himself momentarily off balance, falling back a step or so to gravity. He learned with the grade, planted a hand on a knee. For a minute he hung there, gathering his strength, soliciting his will. With a push and an oath, he drove himself on. A tumble of shale blocked his path. One up, two back, he fought the rotten footing in slipping, stumbling, energy-sapping steps, crabbing to its perimeter, shifting the Parker to his left hand, using his right to pull himself ahead by anything he could grab.

His mouth was cotton dry. The burn in his legs had worsened to a searing ache. Breathing laboriously through his mouth, he hesitated, looking above. Almost halfway yet. He found another piece of candy and stuffed it past his lips, rolling and sucking it to stimulate saliva.

Ben Willow was into himself now, dredging the deepest reserves of his spirit, where the heart and courage of his dogs lay.

He would make it by God! … he would make it.

Rolling his shoulders, he stretched his torso. There was a nagging tightness in his chest.

Through a corner of his mind, a thought of Libby effervesced.

He caught sight of Jenny again, high ahead, nearing the top. Felt his resolve bunch.

His legs stiffened under him, and pumped on. A tortuous 40 yards, then 20 more. Climbing, faltering, then climbing again. Gradually he was winning. He could sense the massive bulk of the mountain below him now, the crown of the ridge close above. The triumph rising.

He dug on, sweating profusely, determined beyond consciousness. With every pull, he gasped in coarse, raspy breaths for air. But the air wasn’t coming fast enough. His heart was pounding, and the exertion was squeezing his chest painfully, relentlessly.

He had to stop. Had to rest. Pulling his hat off he stood straddle-legged on the slope, blowing. Sweating. The pain in his chest was intense. His whole upper body hurt, it seemed. Even his neck and jaw ached. Feeling for the Pepsi, he took along pull, and another, and put it away.

Fretting, he wanted to push on, to regain contact with Jenny. But he felt suddenly weak, with a touch of nausea at his stomach, a little lightheaded. He would rest a bit longer. He took four or five quaky steps to a slab of rock, lowered himself with a hand.

He felt queerly. Vulnerable. Something sinister was suggesting that he would not make the ridge this day, nor any other day ever again. That he would not walk Sam Thomas’ meadow, nor hear the happy gabble of the stream, nor the sweetness of Andrea’s voice, nor see another sunrise of another morning.

He fought it away with the strength of his confidence. He had pushed too hard, yes. Gotten carried away. But he’d sit a minute, let his old body catch up, then go on. Jenny would be back to check on him shortly. He’d call her in and they’d sit a spell and then make the top. He’d done it before. He’d do it again. He rested the gun in his lap, took his hat off again and laid it atop a knee, pulled his bandana out and mopped his forehead.

He was stuffing the bandana back into a pocket when he halted abruptly, stiffening. His face tilted slightly upward and his eyes rolled inquisitively right and stalled. Riveted, he listened with all his might.

“Point!”

He could hear the urgent pulse of the beeper from the ridge. Jenny!

Sixty-four years of conditioning backed the mandate. A collage of a thousand beautiful images, floating across the seasons, spurred the response. Ben Willow slapped his hat on his head, gathered his gun, and struggled off the rock Somehow, he would get there. Somehow, he was going to make it. Jenny was honest. Jenny would wait for him. He reached into himself and grabbed the hill. He fought it with the last reserve of strength his stubborn, hard-crusted old will could muster.

But time had run the river. He had taken little more than a dozen dogged steps when suddenly he could go no farther. His heart was pounding its way through his libs, and there was a crushing, crippling pain at his chest. His breath caught violently; nausea writhed in the pit of his stomach. The whole of his body ran fever-hot, engulfed in a smothering consuming rush. He felt himself go weightless, felt himself falling.

Desperately, he caught the trunk of a small maple, clinging, the Parker dropping from his fingertips and clattering sickeningly among the rocks. The limbs of the trees spun above him in the growing dusk.

And in his last few moments of rationality, all the fears of an old man’s years came crashing down around him, the one above all others.

“No! … No! … Jenny … Je-n-n-eeee, “he pleaded feebly, futily, while the strength ebbed from his fingers and he lost his grasp on the bark of the tree, and consciousness, and slumped, limp, to the ground.

Long strands of white hair spilled loosely against the leaves as his old canvas hat rolled away. He lay upon his back, one leg drawing slowly under the other as his body stiffened, relaxed and quieted. Briefly his eyelids fluttered and a last inaudible word escaped his lips. Three times more his chest rose and fell, then stilled forever.

In the 89th year of his being, Ben Willow had died where most completely he had lived, upon the hills of home, with a dog and a gun. Though the time was not of his choosing, no man could ask for more. He had lived his own life and died his own death.

Fifteen feet away, the old Parker had come to rest also, barrel angled up right against a small face of rock, almost as if someone had sat it there.

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now

From A Higher Hill finds Mike Gaddis atop the enlightening vantage of almost eight decades. Looking back over the vast and enthralling sporting landscape of a life well lived. And ahead, to anticipate and savor whatever years are left to come. Buy Now