Have you ever hunted deer? I do not mean in regions where all you have to do is to go out into the forest with your guide and wait ’til one walks leisurely past you; nor do I mean where dogs drive the creature to water and you can empty the magazine of your Winchester twice over at him; nor yet where the quarry sinks at every step into the crusted snow, ’til so utterly exhausted that it falls victim to the hunting knife. But have you ever hunted deer where hard and skillful work must be done even to catch a sight of them? Where you climb 60-degree slopes at a pace that brings into play every cubic inch of lung capacity, makes the heart drive the blood tingling through every tiny vein and hardens the leg muscles to whipcords?

Where, when, flushed and panting, you sight your game for one brief moment, you know that the one or two bullets you can plump at him must tell roundly, or he’s off, with the chances against his taking the right crossing? Well, if you never have, there is before you excitement and pleasure of the keenest kind. Come with me; let’s try it, as I tried it one ever-to-be-remembered day with a tenderfoot friend in the mountains of West Virginia.

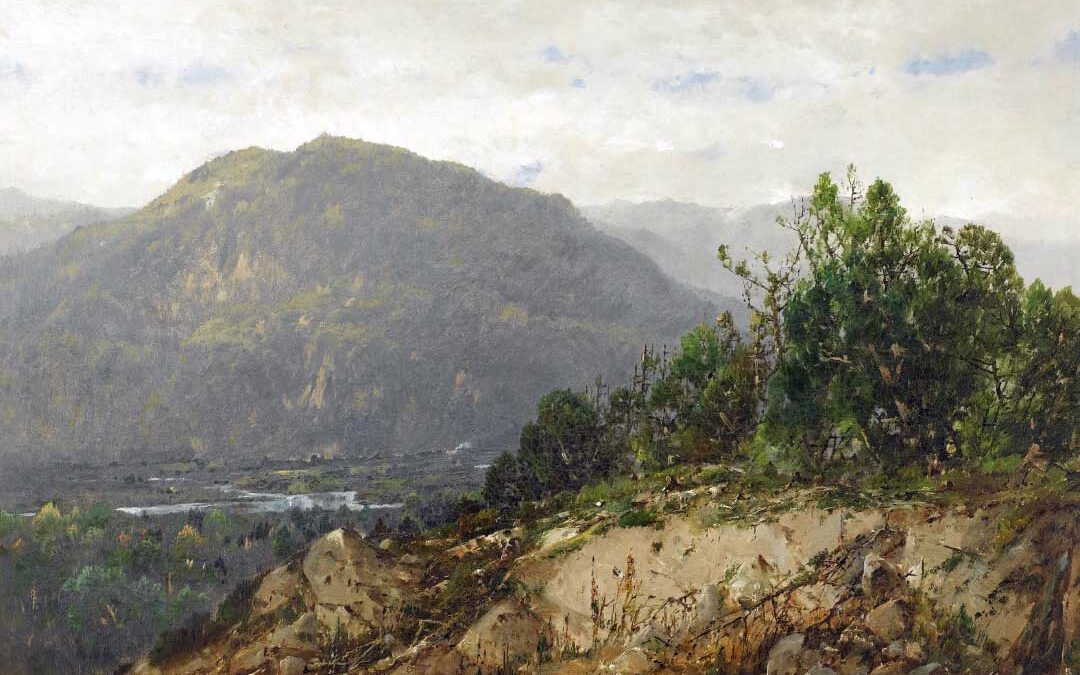

The scene of the hunt was not the “backwoods” counties with their virgin forests and untrailed ranges, but a mountain county on the border with a varied topography of cultivated slopes and bottoms and heavily wooded knobs.

The deer are closely protected there and flock in from the hound-harried regions of Hampshire and Hardy as into a city of refuge of the days of old. Only the initiated are welcomed to hunt in this semi-preserve; a satisfactory introduction is a sine qua non; but to the right persons is extended the heartiest reception. The hunting is of the best and most exciting order, fine sport without amounting to opportunities for wholesale slaughter. You work for what you get, but you get what you work for.

It is Thanksgiving morning at 5:30 o’clock. We ride merrily out of the barnyard, exhilarated by deep, lung-healing draughts of pure, frosty air and watching the brilliant morning star hanging in the pale blue-pink of the eastern sky. Around us rise the great timbered knobs of the West Virginia mountains, towering as much as 2,000 feet above the level of the Potomac, and it is to their crests we are bound. The horses dance about a little. Let them go; the slope will soon take the dance out of them. Half an hour’s ride brings us to a high plateau, above which rise the rounded sugar loaves, called in local parlance “Knobbly Mountain.” Here is a cornfield, the shocks still standing and visited nightly by hungry deer as the network of tracks shows. This is encouraging. Just beyond is a log farmhouse, the rendezvous for the day’s drive. Dim forms flit about in the dusky light, horses stamp, cattle are lowing and a hound tugs eagerly at his chain.

It is a regular gathering of the clans. Three brothers—Elijah, Philip and David—lead the hunt; and no more skilled woodsmen, more unerring shots, more noble, steadfast friends—or more uncompromising enemies—ever trod the mountains.

“Here y’ are at last; glad y’ are on time.”

“We’ll git him to day, boys.”

“Got any buck-fever drops? It’s shiv- erin’ frosty.”

Everybody is talking at once. Merry greetings and banterings pass as one after another comes in. Here is a keen-eyed, well-preserved old man of nearly 70 years. All eagerly welcome him, for he is a prime favorite with a smile and a kind word for every man of us, old friend or total stranger. The tenderfoot is fascinated on the instant and stands intently and confidingly swallowing a tale of some impossible adventure, told with many a sly wink. One can see at a glance that this patriarch is a mighty hunter and a master of woodcraft, for even the great three defer to him and ask his opinions about the chase. As we drive or go from crossing to crossing, we shall hear today many a tale of his prowess with the rifle. At this moment our chief, Elijah, comes, rifle in hand, from the house where he has been making final arrangements with his wife for dinner for the entire troop. Herself a sportswoman of no mean order, she follows her husband to wish us luck.

The patriarch gallantly salutes: “Good mornin’, ma’am; goin’ with us today? But co’se yo’ are, to bring luck.”

“Not today, Mr. Jim, with all this mob to cook for. But I’m glad to see you up. Anybody come up with you?”

“No’m, nobody with me, nobody ’t all; only that fellow they call Jake Leaf come with my dawgs.” (Jacob evidently ranks low as a hunter in the master’s eye. I should be glad to possess his skill.)

“What dawgs, suh? you say. Only them bank-note-eared, whip-cracker-tailed pups o’ mine. Not much good, suh, an’ not fo’ deer, but might start a fox.” This last in answer to a question from me. It is a cunning evasion of the law, for the dogs will surely rouse a deer and then be taken off the trail.

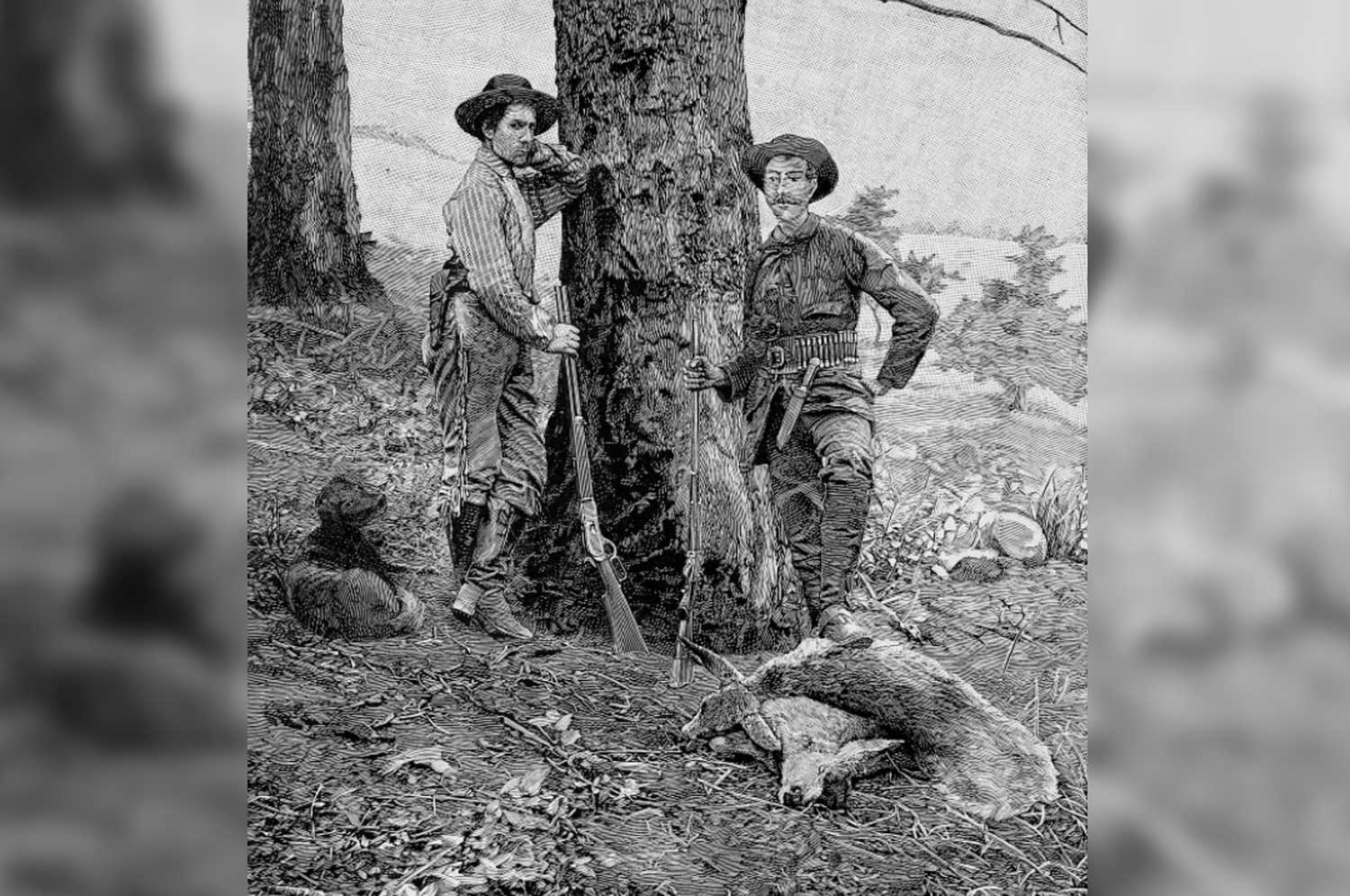

Whitetail Deer by Tom Beecham

But it is time to start the first drive. The crowd is divided. Part are ordered to the crossings to await the coming of the deer, and woe to the luckless green horn who shoots at anything but a deer or leaves his post unordered. It is a trying thing to sit motionless, with what feelings may be imagined, and watch a dozen wild turkeys file past in a bunch and beautiful foxes slip by within 20 feet, and not dare to pull the trigger. No matter how much one longs to do it, it dare not be risked, or the offender is anathema through the length and breadth of the region.

Off we go, all together. A turn in the road reveals two tall, thin, weather-beaten men, as much alike as two peas, with long, tangled beards reaching to their waists, and elongated muzzleloading shotguns reaching to their chins. They cower over a little fire and rise stiffly to join the crowd. Both produce bottles of boiled cider with grains of rye bobbing about in it and pass them around.

“Better be a leetle keerful,” says one. “It’s pow’ful strong, an’ it’ll make the drunk come quick.”

We taste, the tenderfoot and I, and are in future “keerful.” The mixture is vile. This pair are typical native mountaineers. The other men, more active and vigorous, have come in from other states to ’til

their mountain farms, and with them “Virginian” is an epithet carrying no small flavor of slur. But every little helps on a deer hunt, and they are assigned to the drive.

“Well, boys,” calls our leader cheerily, “we ought to be at work now. Git to the crossin’s lively; we’ll give you fifteen minutes. Davy, you go to the trough; you take the big red oak, Billy; a rifle’s needed there.” And so the men are stationed, with as careful strategy as a regiment on the eve of battle.

The “crossings” are points in a valley where a deer crosses from one ridge to another. The deer’s lair is in the dense thickets on the crest, and when driven out by man or dog, or even when merely in quest of food or water, he always runs in one of a few fixed routes, a fatal instinct. Hunting with dogs is no longer legal in West Virginia, and the drives are made by men. We are driving this time, and inside of five minutes we’ll know how it’s done and what it means in the way of work. Digging potatoes, grubbing stumps, splitting rails, “snaking” mine-props, are child’s play in comparison—queer that perverse humanity likes this best. We are stationed 50 to 100 yards apart, a dozen of us in line and, at a yell from the leader, plunge forward up the ridge

Pandemonium is let loose upon the hush of the autumn dawn, for every driver is yelling as seemeth unto him good, preferably imitating the baying of hounds. Barks, yelps, howls, whines, squeals, wild yells, in every possible and impossible pitch of a dog’s voice echo from ridge to ridge. A dog pound is loose with a ward school in pursuit. Every living thing on the mountain flees before that demoniac skirmish line. Up jumps a pheasant. Bang! comes from a shotgun. Everything with fur or feather is legitimate game on the drive. On we go, scrambling up from rock to rock, pulling from tree to tree.

“Will we never reach the top?” yells the exhausted tenderfoot.

“Yes, and you’ll wish you hadn’t.”

Out flies a big turkey, but no one gets a shot. The great trees stand wider apart and are draped with graceful wild grapevines laden with frost-ripe clusters. Now the slope is less steep, and we breathe easier, but wind or no wind, keep up that infernal yawp. There’s the thicket ahead. Plunge in, no shirking! Young locust trees grow thick on the summit plateau; each one is about 2 inches in diameter and full of the wickedest, most obtrusive thorns imaginable. They grow there by the thousands and tens of thousands; “’nuf t’ fence in all West Virginia,” as one old native put it.

“Do you know now what deer driving means, Tenderfoot?” I sing out to him, but he’s too deeply involved to answer. The thorns catch us by sleeve and trousers leg. They steal our hats. They collar us. They buttonhole us worse than candidates before election. Thicker and thicker! Blackberry vines grow up densely just to fill in and economize space, and the whole mass is woven and plaited together with greenbrier. Faces and hands are bleeding; but straight ahead! If you can’t get through edgeways, turn yourself into a revolving wedge and go through by main strength.

Out of the thicket and on the steeps again; downhill now and dead easy. We can at last steal a moment to enjoy the superb landscape. All West Virginia seems unfolded before us. The timbered heights of range succeeding range roll away far as the eye can reach. The mellow light of the rising sun touches them with glory, and a kaleidoscope of marvelous color effects responds to the touch of that wand of gold. The yellows and browns and grays of faded leaf and sturdy trunk in the foreground blend in the middle distance to the richest of golden browns and far away are softened and beautified to an exquisite purple haze, as though the nature-goddess masqueraded in finest gauze. But no time for this. On, and down the mountain. The drive is over and nothing to show for it.

A hasty conference, and the party separates for the next drive. The crossing men drive now; and we, tired and breathless, go to the stands assigned us to recover our nerve and wait for the deer. An excellent stand is selected for the tenderfoot this time; Elijah is generous and gives visiting friends the best crossings, a thing not always done in these mountains, I can tell you. A dry watercourse runs by the base of a high and steep ridge, heavily timbered and singularly free from undergrowth. An enormous hickory stands back 20 yards from the rocky stream bed, and in front of it is a curious flat place, washed out by some storm-born torrent. It is at these depressions, or “sinks,” that a deer always elects to cross a washout.

“Tenderfoot, let me give you a little advice before we start the drive, and a warning of what to expect. Remember to follow instructions, for I know just what’s going to happen, if anything happens at all. Down you go behind an old stump. Luckily, the wind is blowing right in your face; if it were at your back the deer would scent you to the very summit and turn. All is quiet now. Every nerve is strained. Commune with yourself a little and tell yourself to keep calm and aim at the deer as at a paper target. Men miss a deer because every attentive faculty is strained and centered upon the animal and intervening objects, rifle sights included, are as if they were not, and are utterly disregarded. Reason thus, and if your heart beats ’til it hurts your ribs as a gray squirrel whisks across the dry leaves or a ‘grinny chipmunk’ waves you a derisive signal with his little flag from a log before your very nose, call yourself ‘fool,’ ‘idiot,’ anything that comes handy. It’ll do you good; truth always does.

“Your eyes are glued to the mountain side before you. A graceful silhouette stands against the sky on the very crest. Your eyes bulge from your head; your heart is in your throat. It is an agonizing moment. Will he turn? Will he go to the other fellow? No; he runs straight to you in a gentle, easy skip. He stops, turns his head, and listens. Oh, that head! ‘A reg’lar rockin’ cheer’ on it. He hears a yell and bounds toward you. Talk to yourself; you need it now. A deer’s slow approach is above all things most trying. Better for the nerves to have him break out at you on the run from densest brush. On he comes, an easy walk now. What dainty, aristocratic stepping! You want to get up and yell. Closer; your nerves quiet down a little. Cover him now; he’s not more than 100 yards away. Cover him and sight anew every yard he walks.

“He’s at the stream. He stops, turns aside to look up the ridge. He’s in no hurry, for there are no dogs. Now is the time, and the place is behind the shoulder. With the ringing crack of the Winchester—if you have held straight—he bounds wildly and starts up the slope like an arrow. You will probably forget the well-filled magazine and watch him with the worms gnawing at your heart. A great fallen tree bars his way; he springs; his knees strike; over he rolls and lies motionless. You will be in the seventh heaven then, and the worms will be angels fanning you with their wings. Let out a Comanche screech, if you want to; but stay where you are; let him lie still and bleed. To rush at him might awaken a burst of dying energy that would carry him a mile and you too unstrung to stop him.”

We left the tenderfoot to his reflections and, as luck would have it, the deer came in to him. My forecast came true to the letter, and he scored the first deer he had ever shot. He confided to me that he had to keep gulping down his heart from first sight of the deer ’til, by the soliloquizing plan I had advised, he had steadied himself for the shot. “I owe that fellow to you, old man,” he said warmly, and I believe he did.

We start in to dinner, for the morning is far spent; but as we pass a house in a pretty mountain meadow, a man excitedly rushes out shouting that six deer have just come in from the ridge, fed awhile among his sheep and drifted lazily off over the next hill. Dinner is forgotten. Plans are laid in a trice, grand strategy and tactics. We are off to the crossings again. We know from the direction taken that this will be a long drive, and for three hours we bask in the warm, genial sunshine, impatient and hungry. Here come the drivers at last, toiling wearily up the slope.

“Boys, our deer’s killed an’ stole!”

Some miscreant, knowing of the hunt, has quietly preempted a crossing, killed the deer and swiftly sneaked away with it, the meanest trick in the hunter’s ethical code.

“Can’t blame him fer killin’ it, but to take it off that way is worse ’n stealin’ sheep.”

The first blood takes the hide and hind quarter, not an ounce more, and the rest is divided. Had he waited and made the division he could have been pardoned. But now a council of war is held. It is known who has the deer and where he has taken it; clear out of the state, over the river to a little town in Maryland. The drivers were close upon the trail. Everyone is enraged at the stranger’s nerve, and it is evident that the Monroe Doctrine will be vigorously upheld. Virginia game for Virginians!

“We’ll have our rights or lick all Cresaptown,” is the climax finally reached. “Who’ll go with me, men?” cries Philip.

Volunteers are numerous. Back we go to the house to the best dinner ever served, for hunger was our sauce, and our relish, keenest repartee and wit, none the less trenchant for being unpolished. Dinner over, horses are hurriedly saddled, and the “Cresaptown Cavalry” is off for the raid.

It was a sight to see all those broad-backed mountaineers galloping off to right their wrongs in the swift, direct style of the mountains.

“We can clean out the town, men,” called our leader, and it was no idle boast.

“It’ll scare ’em blue just to git one look at the shoulders of this gang.”

It was a foolish, reckless escapade, perhaps, but we were in it to see it through with our friends, and Jesse James himself never was more thoroughly in earnest. We reached Cresaptown at dark and found our man just in the act of dressing the deer. A committee of two was appointed to state the case. It was stated. Never was statement clearer, and the logic was convincing. But I draw the curtain. We rode back, the Light Brigade, the Cresaptown Cavalry, six strong, by the silver light of the fullest moon that ever shone. Jests and merry tales rang upon the still night air, and the deer was slung across the horse of the writer.

This article originally appeared in the November 1898 issue of Outing.