I have several times shot white goats for the sake of the trophies afforded by the horns and skins, but I have never gone after them much, as the work is very severe and the flesh usually affords poor eating, being musky, as there is a big musk-pod situated between the ear and the horn. Only a few of the old-time hunters know anything about white goats, and even nowadays there are not very many men who go into their haunts as a steady thing. But the settlers who live high up in the mountains do come across them now and then, and they occasionally have odd stories to relate about them.

One was told to me by an old fellow who had a cabin on one of the tributaries that ran into Flathead Lake. He had been off prospecting for gold in the mountains early one spring. The life of a prospector is very hard: He goes alone, and in these northern mountains he cannot take with him the donkey which, towards the south, is his almost invariable companion and beast of burden. The tangled forests of the northern ranges make it necessary for him to trust only to his own power as a pack-bearer, and he carries merely what he takes on his own shoulders.

The old fellow in question had been out for a month before the snow was all gone, and his dog, a large and rather vicious hound to which he was greatly attached, accompanied him. When his food gave out he was working his way back towards Flathead Lake. There he struck a stream on which he found an old dug-out canoe, deserted the previous fall by some other prospector or prospectors. Into this he got, with his traps and his dog, and started downstream.

On the morning of the second day, while rounding a point of land, he suddenly came upon two white goats, a female and a little kid, evidently but a few weeks old, standing right by the stream. As soon as they saw him they turned and galloped clumsily off towards the foot of the precipice. As he was in need of meat, he shoved ashore and ran after the fleeing animals with his rifle while the dog galloped in front.

Just before reaching the precipice the dog overtook the goats. When he was almost up, however, the mother goat turned suddenly around, while the kid stopped short behind her, and she threatened the dog with lowered head. After a second’s hesitation the dog once more resumed his gallop and flung himself full on the quarry.

It was a fatal move. As he gave his last leap, the goat, bending her head down sideways, struck viciously, so that one horn slipped right up to the root into the dog’s chest. The blow was mortal, and the dog barely had time to give one yelp before his life passed.

It was, however, several seconds before the goat could disengage its head from its adversary, and by that time the enraged hunter was close at hand, and with a single bullet avenged the loss of his dog. When the goat fell, however, he began to feel a little ashamed, thinking of the gallant fight she had made for herself and kid, and he did not wish to harm the latter. So he walked forward, trying to scare it away, but the little thing stood obstinately near its dead mother and butted angrily at him as he came up. It was far too young to hurt him in any way, and he was bound not to hurt it, so he sat down beside it and smoked a pipe.

When he got up it seemed to have become used to his presence, and no longer showed any hostility. For some seconds he debated what to do, fearing lest it might die if left alone; then he came to the conclusion that it was probably old enough to do without its mother’s milk, and would have at least a chance for its life if left to itself. Accordingly, he walked towards the boat; but he soon found it was following him. He tried to frighten it back, but it belonged to much too stout-hearted a race to yield to pretense, and on it came after him.

When he reached the boat, after some hesitation he put the little thing in and started downstream. At first the motion of the boat startled it, and it jumped right out into the water. When he got it back, it again jumped out, this time onto a boulder. On being replaced the second time, it made no further effort to escape; but it puzzled him now and then by suddenly standing up with its fore-feet on the very rim of the ticklish dugout, so that he had to be very careful how he balanced. Finally, however, it got used to the motion of the canoe, and it was then a very contented and amusing passenger.

The last part of the journey, after its owner abandoned the canoe, was performed with the kid slung on his back. Of course, it again at first objected strenuously to this new mode of progress, but in time it became quite reconciled and accepted the situation philosophically. When the prospector reached his cabin his difficulties were at an end, but the little goat had fallen off very much in flesh; for though it would browse of its own accord around the camp at night, it was evidently too young to take to the change kindly.

Upon reaching the cabin, however, it began to pick up again, and it soon became thoroughly at home amid its new surroundings. It was very familiar, not only with the prospector, but with strangers, and evidently regarded the cabin as a kind of safety spot. Though it would stray off into the surrounding woods, it never ventured farther than 200 or 300 yards, and after an absence of half an hour or so, at the longest, it would grow alarmed and come back at full speed, bounding along like a wild buck through the woods until it reached what it evidently deemed its haven of refuge.

Its favorite abode was the roof of the cabin, at one corner of which, where the projecting ends of the logs were uneven, it speedily found a kind of ladder, up which it would climb until the roof was reached. Sometimes it would promenade along the ridge, and at other times mount the chimney, which it would hastily abandon, however, when a fire was lit.

The presence of a dog always resulted in immediate flight, first to the roof, and then to the chimney. When it came inside the cabin, it was fond of jumping on a big wooden shelf above the fireplace, which served as a mantelpiece.

If teased it was decidedly truculent, but its tameness and confidence, and the quickness with which it recognized any friend, made it a great favorite, not only with the prospector, but with his few neighbors.

However, the little thing did not live very long. Whether it was the change of climate or something wrong with its food, when the hot weather came on it pined gradually away, and one morning it was found dead, lying on its beloved roof-tree. The prospector had grown so fond of it that, as he told me, he gave it a burial “just as if it were a Christian.”

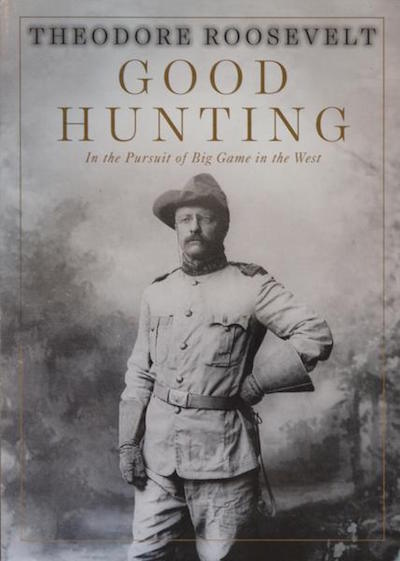

“A Tame White Goat” is one of several Roosevelt stories published in Good Hunting: In Pursuit of Big Game in the West. The collection brings together TR stories not found in other titles like Wilderness Hunter or The Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, and is an invaluable addition to any sportsman’s library. Order a copy today in the Sporting Classics Store.