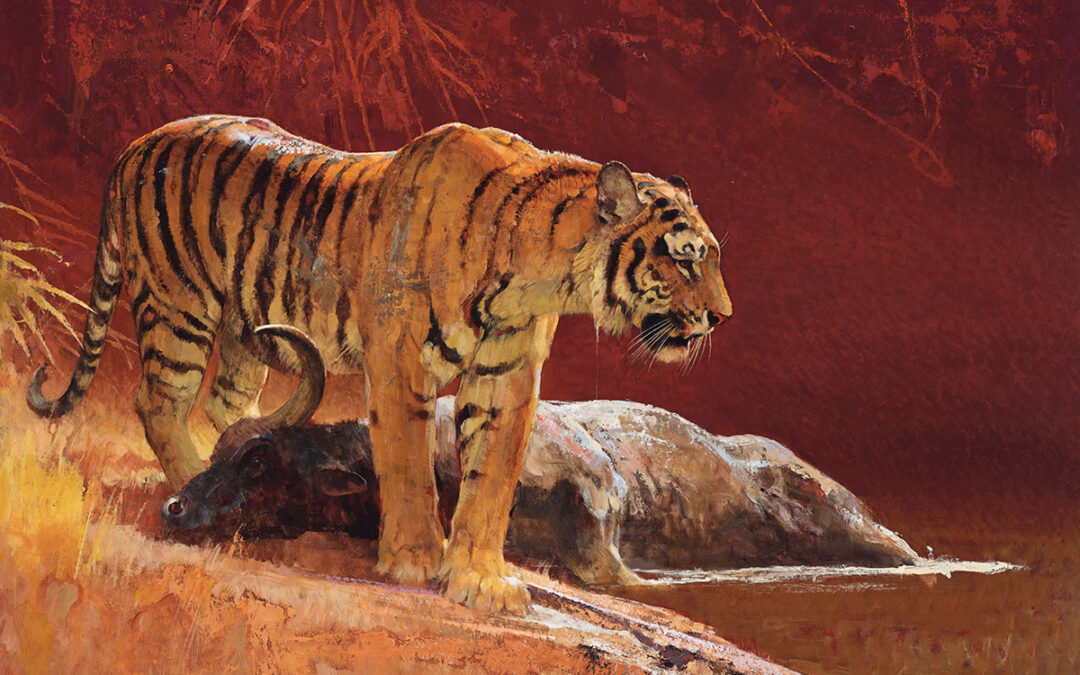

The Landing of a Wildlife Masterwork Once Belonging to T. Boone Pickens Now Available for the Public to Savor. This is Bob Kuhn’s elusive tiger.

Our eyes are drawn first inexorably to the carnivore paused peacefully in the aftermath of a kill. There is something sensuous about this beast in the Indian jungle, so calming that it allows you to look past the danger before you realize what’s at the predator’s feet.

A Stillness by the Pool, an acrylic painting by the late Bob Kuhn (1920-2007), is considered one of his greatest masterworks. Just as The Mona Lisa, today in the Louvre, attests to the genius of Leonardo da Vinci who created a human portrait for the ages, Kuhn’s portrayal of a tiger is illustrative of the highest potential of contemporary wildlife art.

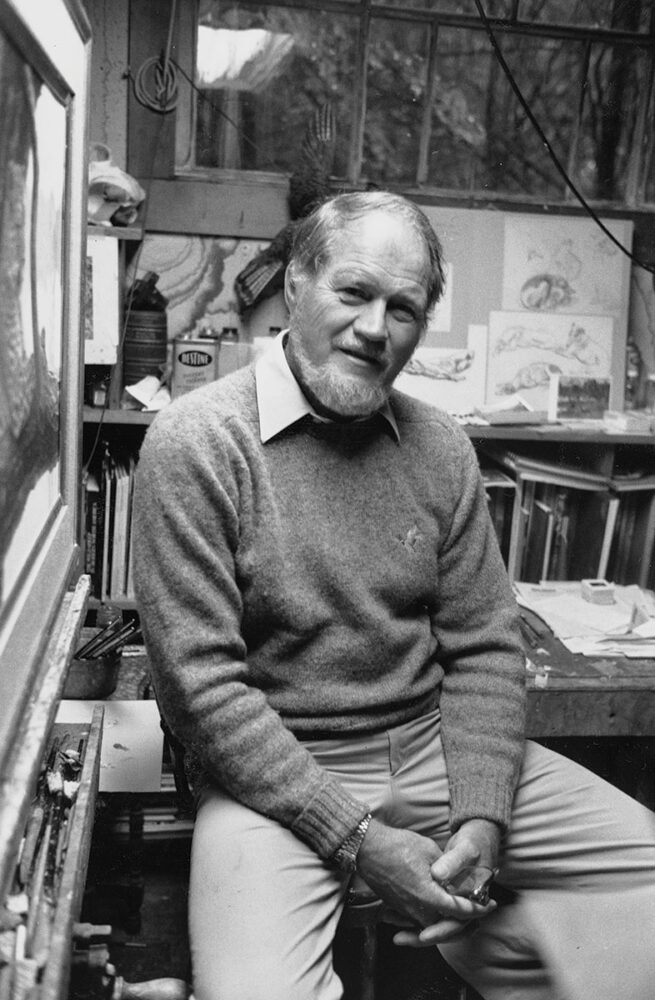

Not long ago, the 1981 work went up for auction in New York City, where Christie’s was showcasing the finest art pieces acquired by the late energy industry wildcatter, businessman and ardent Texas sportsman, T. Boone Pickens.

Art collecting can be a fickle and agonizing sport. Like a big shadowy fish that suddenly emerges and passes beneath the boat in silhouette, or a near-mythical bull elk that appears yet vanishes quickly in the timber, art treasures can be evasive and elusive. Pass up the opportunity to own an extraordinary painting or sculpture in a given moment when the stars have aligned, and that fleeting chance may never happen again.

Robert F. Kuhn (American, 1920-2007), The Eye of the Beholder, 1994. Acrylic on board. 29 1/2 x 40 inches. JKM Collection®, National Museum of Wildlife Art. © Estate of Robert F. Kuhn

Forever, the missed opportunity looms not as the one that almost was but the prize that got away. A Stillness by the Pool had been that piece for Bill and Joffa Kerr, collectors and founding co-patrons of the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming, that today has the premier public assemblage of Kuhn paintings in the world.

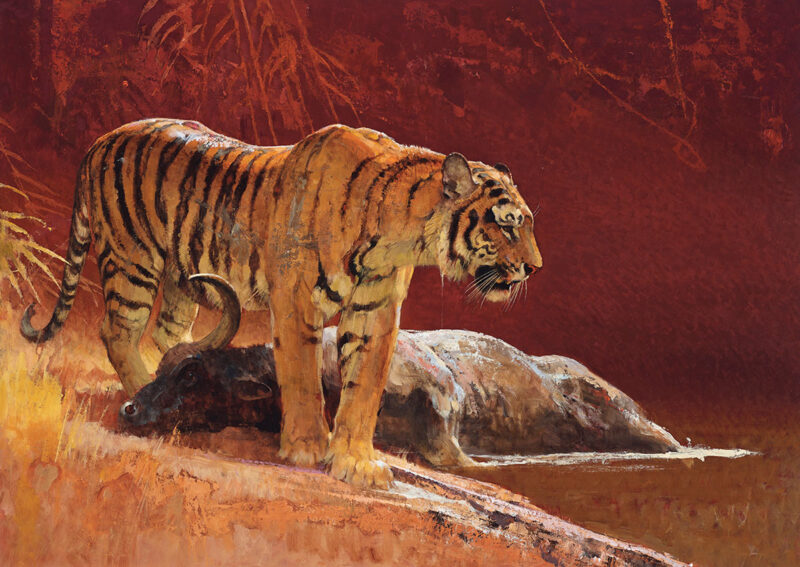

Kuhn became known to generations of sporting people in the post WW II 1940s when, and for the next three decades, his original presentations of big game animals and hunting scenes appeared on the covers and as illustrations in the largest circulation outdoor magazines in the land. In addition, his paintings were featured in the annual Remington Arms calendar, giving him an endearing presence in millions of homes and workplaces across the country.

For years, the native of Buffalo, New York, and graduate of the Pratt Institute in New York City where he was influenced by the “color field” designs of abstract painter Mark Rothko, lived in Connecticut among the best illustrators in America. As photography replaced original art in advertising and magazine graphic design, Kuhn headed west and resettled in Tucson, Arizona, to focus on painting.

His dramatic and often playful depictions of large game animals were often scenes of subjects set in motion, presented with backdrops of banded colors that, along with seizing our attention, evoked moods in our response. Kuhn was the farthest thing from being a photo-realistic documentarian—a paint every hair on a brown bear’s back. Rather, akin to fine artist Carl Rungius—vaunted as the greatest painter of North American big game animals—Kuhn could have painted any subjected and gained renown, but he chose wildlife because their being resided in his heart.

Robert F. Kun (American, 1920-2007), Buffalo Bulls Emerging from Papyrus, 1984. Acrylic and pencil on masonite. 30 x 45 inches JKM Collection®, National Museum of Wildlife Art. © Estate of Robert F. Kuhn

Kuhn’s early years overlapped with Rungius’s final third of life, and he has been hailed for carrying on the mantle of elevating wildlife art out of its status as being only a visual fetish for hunters and anglers.

The Kerrs took notice of Kuhn’s easel paintings in the 1960s, particularly after he arrived in Tucson and then began making research forays to the Rockies, Canada/Alaska and Africa. Kuhn and a handful of wildlife art contemporaries— Robert Bateman, David Shepherd, Simon Combes, sculptor Ken Bunn and others—became sensations at the Game Coin International shows in San Antonio. During Game Coin’s heyday, Kuhn came to the attention of Dallas art dealer and national champion trap and skeet shooter, Martin F. “Bubba” Wood, founder of the legendary Collector’s Covey gallery and outdoor store.

Wood was one of Pickens’ closest friends and, appropriately, he received the T. Boone Pickens Lifetime Sportsman Award at the Park Cities Qual Coalition’s meeting earlier in 2021.

Kuhn’s status as a living master of wildlife art was unsurpassed and his works were highly coveted. Particularly noteworthy is that he could handle African scenes as deftly as animals in North America. His prowess was demonstrated most poignantly in portrayals of wild cats—cougars, bobcats, African lions, leopard, jaguars—any species.

He had a remarkable ability to communicate the sleek sinuous fluidity of felines and he would spend hours drawing, doodling thumbnails even while watching movies with his wife, Libby, trying to perfect the spirit of cats as they stalked and sleeked, relaxed and pounced.

Robert F. Kuhn (American, 1920-2007), Heading Into Thick Stuff. Acrylic on masonite. 24 x 42 inches. JKM Collection®, National Museum of Wildlife Art. © Estate of Robert F. Kuhn

A Stillness by the Pool had been on the museum’s wish list and there was an initial attempt made by the Kerrs when Bubba Wood had access to it off the easel, but Pickens knew instantly what was in front of him. Dr. Adam Duncan Harris, the Grainger/Kerr director of the Carl Rungius Catalogue Raisonné project at the National Museum of Wildlife Art explains:

“Some 15 years ago when I was researching my book on the business and conservation passions of Ted Turner, I interviewed Pickens, who was a close friend of Turner. Part of our conversation drifted to sporting art and Bubba Wood and Pickens’ favorite pieces. Wood once told me that Kuhn’s tiger piece ‘in my humble opinion rated a 14 on a scale from 1 to 10.’”

For Pickens, the painting, among thousands of collectible things he had amassed over his life including shotguns, ranked near the top in his art collection.

Sue Simpson Gallagher, hired as the National Museum of Wildlife Art’s first curator in the 1980s, has served as a museum trustee for 18 years. Today she operates the Simpson Gallagher Gallery in Cody, Wyoming. She thinks of the Kuhn tiger painting as being part of a friendly rivalry.

“Picture this—T. Boone Pickens and Bill Kerr—Oklahoma boys. Oklahoma legends who dedicated large portions of their lives to collecting art,” she says. “Two brilliant minds dedicated to educating themselves and creating a legacy not for themselves but for the artists and their genre.”

Harris says the Kuhn tiger painting holds its own against works created by Old World masters.

Robert F. Kuhn (united States, 1920-2007), the Return of the Caribou, 1995. Acrylic on board. 24 x 30 inches. JKM Collection®, National Museum of Wildlife Art. © Estate of Robert F. Kuhn

“I am really drawn to the darker pieces he did,” Harris notes of Kuhn, mentioning a portrayal of bison piece titled Nothing But Time and a portrayal of a jaguar and cattle egrets. Of A Stillness by the Pool, in which Kuhn sets the tone by daringly using non-traditional, non-literal color selections to frame the tiger, Harris notes, “That use of dramatic lighting and beautiful colors creates a dark atmosphere. He definitely enjoyed experimenting with reds and taking one color and using it as a theme in a Mark Rothko kind of way.”

The foreground and background are non-detailed negative space that converges in the middle lining up the tiger as our powerful focal point, but it is the crimson hue that creates the mood. While the setting is near a jungle pool, there’s no blue or other color insinuating the presence of water in sight.

Harris notes that this masterwork is “definitely not like your standard stag in the forest depiction that looks tired and manipulated. This painting gives us both a believable scene and it has gorgeous composition. All of the things that Kuhn was known for being great at came together.”

Jolting about A Stillness by the Pool is how much it grips us as a paradox playing off the title. It is a scene of serenity, yes, but it comes at the end of a violent predation, after the subject has taken down an Indian gaur. With the tiger gazing toward water, our eye is released and we see it standing over its next meal.

Robert F. Kuhn (American, 1920-2007), Jaguar and Cattle Egrets, 1980. Acrylic and pencil on board. 18 x 40 inches. JKM Collection®, National Museum of Wildlife Art. © Estate of Robert F. Kuhn

As was typical, Kuhn was self-deprecating when critics called his color choices ingenious. It is the holy duty of an artist to constantly be pressing the bounds of what is safe, known, comfortable and boring; it is the only route forward that leads to the joy of undiscovered destinations.

He told author Tom Davis in a book about Kuhn published by Sporting Classics in 1997: “Among the silly taboos regarding color that I’ve heard over the years, one is ‘don’t mix orange and red.’ The logical response would be, ‘which orange and which red?’ One of the reasons I took on this project was that I wanted to place the orange tiger and his recently vanquished prey (a female gaur) against a rich, dark-red background. I liked what happened, and so it stands today. It is one of the innumerable examples of a painter experimenting with new color and spatial relationships, deciding that the results are worth preserving, and then being credited with having profound theories regarding design and color.”

Pickens died on Sept. 11, 2019 and there remains an enduring lesson in the handling of his estate. Great one-of-a-kind fine art maintains its worth. It is more satisfying than hoarding gold and stowing precious metal away in a safe as a hedge. What Pickens savored was having ready access to Kuhn’s painting that gave him visual pleasure money can’t buy.

Robert F. Kuhn (American 1920-2007), A Stillness by the Pool, 1981. Acrylic on masonite. 30 x 42 inches. JKM Collection®, National Museum of Wildlife Art. © Estate of Robert F. Kuhn

Kerr has always looked to enhance and strengthen the museum’s permanent collection. “His photographic memory and sleuthing ability has led him to find hidden treasures,” Simpson Gallagher says. “In the case of A Stillness by the Pool, he knew the piece and had to have it. That’s that.

“In some ways, the stage was set. Kerr realized how difficult it is to find a bonafide Kuhn masterwork out in the world anymore,” Simpson Gallagher said.

On October 28, 2020, Christie’s opened the bidding A Stillness by the Pool, with an estimated value range of between $200,000 and $300,000. The Kerrs, who saw the piece as an important Kuhn capstone and wanted the public to be able to enjoy it, knew how going after a “priceless” creative work may allow only one shot in a lifetime.

Kuhn’s prestige has soared in the wake of his passing. When the gavel came down, A Stillness by the Pool realized $400,000 and its new home is in a museum that Kuhn loved, that is itself a one of a kind institution in the world—a place where artistic celebration of wildlife in its habitat is de rigueur.

“I think you can’t ever overstate that thing we talk about with wildlife art, that it was/is a relatively underappreciated genre until brought to the attention of art historians that it’s not about the subject; it’s about the execution, skill and craftsmanship,” Simpson Gallagher says.

Be one a hunter, angler, tree-hugger, conservative, liberal, urban dweller, city slicker or person who grew up on a farm or ranch, the National Museum of Wildlife Art is the place where all of us, who can’t imagine Earth without wildlife in it, exists as a place where we are welcomed on an art pilgrimage. Awaiting us is a collection nonpareil.

Robert F. Kuhn

“Bill and Joffa’s commitment to collecting and sharing their art collection with the public is unprecedented. They were patrons and friends of Bob Kuhn and, at a time when museums were cautious about collecting living artists, they boldly chose to do so because they believed wholeheartedly that his work belonged among the masters of wildlife art,” Simpson Gallagher says.

Regarding this latest addition to the museum’s astounding collection, she adds, “We may never have seen a tiger outside of a zoo, but we know that that environment feels right, and the gesture of the animal reads well because we know Bob Kuhn knew his subject.”

The work is likely to inhabit a special space in the museum that is colloquially known as “the Kuhn rotunda.” It is a stretch of gallery situated between walls holding Kuhn’s hero, Rungius, and a place devoted to modernism with Kuhn serving as an important bridge in art history.

If Kuhn himself had known the painting would eventually find its way to a permanent home in Jackson Hole, courtesy of his dear friends, Bill and Joffa Kerr, he would’ve been enormously satisfied indeed.

No animals ever captured man’s imagination like the big five of Africa: lion, leopard, elephant, rhino and Cape buffalo. Tony Dyer, so proficient with his pen, and Bob Kuhn, and illustrator equally proficient with his paintbrush introduce these animals to us all. This revised edition contains six colored tip in sheets, hundreds of black and white drawings and over 40 photographs that were never included in the first edition. Buy Now

No animals ever captured man’s imagination like the big five of Africa: lion, leopard, elephant, rhino and Cape buffalo. Tony Dyer, so proficient with his pen, and Bob Kuhn, and illustrator equally proficient with his paintbrush introduce these animals to us all. This revised edition contains six colored tip in sheets, hundreds of black and white drawings and over 40 photographs that were never included in the first edition. Buy Now