In this fascinating excerpt from African Game Trails, TR lives up to his ‘stand firm’ philosophy as he takes on a charging lion.

On this same evening we rode campward facing a wonderful sunset. The evening was lowering and overcast. The darkening plains stretched dim and vague into the far distance. The sun went down under a frowning sky, behind shining sheets of rain; and it turned their radiance to an angry splendor of gold and murky crimson.

At this camp the pretty little Livingstone’s wheatears, or chats, were very familiar, flitting within a few yards of the tents. They were the earliest birds to sing. Just before our eyes could distinguish the first faint streak of dawn, first one and then another of them would begin to sing, apparently either on the ground or in the air, until there was a chorus of their sweet music. Then they were silent again until the sun was about to rise. We always heard them when we made a very early start to hunt.

By the way, with the game of the plains and the thin bush, we found that nothing was gained by getting out early in the morning; we were quite as apt to get what we wanted in the evening or indeed at high noon.

The last day at this camp Kermit, Tarlton and I spent on a 12-hour lion hunt. I opened the day inauspiciously, close to camp, by missing a zebra, which we wished for the porters. Then Kermit, by a good shot, killed a tommy buck with the best head we had yet gotten.

Early in the afternoon we reached our objective, some high koppies, broken by cliffs and covered with brush. There were klipspringers on these koppies, little rock-loving antelopes, with tiny hoofs and queer brittle hair; they are marvelous jumpers and continually utter a bleating whistle. I broke the neck of one as it ran at a distance of a 150 yards; but the shot was a fluke, and did not make amends for the way I had missed the zebra in the morning. Among the thick brush on these hills were huge euphorbias, aloes bearing masses of orange flowers, and a cactus-like ground plant with pretty pink blossoms. All kinds of game from the plains, even rhino, had wandered over these hill-tops.

But what especially interested us was that we immediately found fresh beds of lions, and one regular lair. Again and again, as we beat cautiously through the bushes, the rank smell of the beasts smote our nostrils.

At last, as we sat at the foot of one koppie, Kermit spied through his glasses a lion on the side of the koppie opposite, the last and biggest; and up it we climbed. On the very summit was a mass of cleft and broken boulders, and while on these Kermit put up two lions from the bushes which crowded beneath them.

I missed a running shot at the lioness as she made off through the brush. He probably hit the lion, and very cautiously, with rifles at the ready, we beat through the thick cover in hopes to find it; but in vain. Then we began a hunt for the lioness, as apparently she had not left the koppie.

Soon one of the gun-bearers, who was standing on a big stone, peering under some thick bushes, beckoned excitedly to me; and when I jumped up beside him he pointed at the lioness. In a second I made her out. The sleek, sinister creature lay not ten paces off, her sinuous body following the curves of the rock as she crouched flat looking straight at me. A stone covered the lower part, and the left of the upper part, of her head; but I saw her two unwinking green eyes looking into mine.

As she could have reached me in two springs, perhaps in one, I wished to shoot straight, but I had to avoid the rock which covered the lower part of her face, and moreover I fired a little too much to the left. The bullet went through the side of her head, and in between the neck and shoulder, inflicting a mortal, but not immediately fatal, wound. However it knocked her off the little ledge on which she was lying, and instead of charging she rushed uphill.

We promptly followed, and again clambered up the mass of boulders at the top. Peering over the one on which I had climbed, there was the lioness directly at its foot, not 12 feet away, lying flat on her belly; I could only see the aftermost third of her back. I at once fired into her spine; with appalling grunts she dragged herself a few paces downhill; and another bullet behind the shoulder finished her.

She was skinned as rapidly as possible, and just before sundown we left the koppie. At its foot was a deserted Masai cattle kraal and a mile from this was a shallow, muddy pool, fouled by the countless herds of game that drank thereat. Toward this we went, so that the thirsty horses and men might drink their fill. It was already too dusk for good shooting, and we were rather relieved when, after some inspection, they trotted off and stood at a little distance in the plain. Our men and horses drank, and then we began our ten miles’ march through the darkness to camp.

One of Kermit’s gun-bearers saw a puff adder (among the most deadly of all snakes); with delightful nonchalance he stepped on its head, and then held it up for me to put my knife through its brain and neck. I slipped it into my saddle pocket, where its blood stained the pigskin cover of the little pocket Nibelungenlied, which that day I happened to carry.

Immediately afterward there was a fresh alarm from our friends the three rhinos; dismounting, and crouching down, we caught the loom of their bulky bodies against the horizon, but a shot in the ground seemed to make them hesitate, and they finally concluded not to charge. So, with the lion skin swinging behind two porters, a moribund puff adder in my saddle pocket, and three rhinos threatening us in the darkness to one side, we marched campward through the African night.

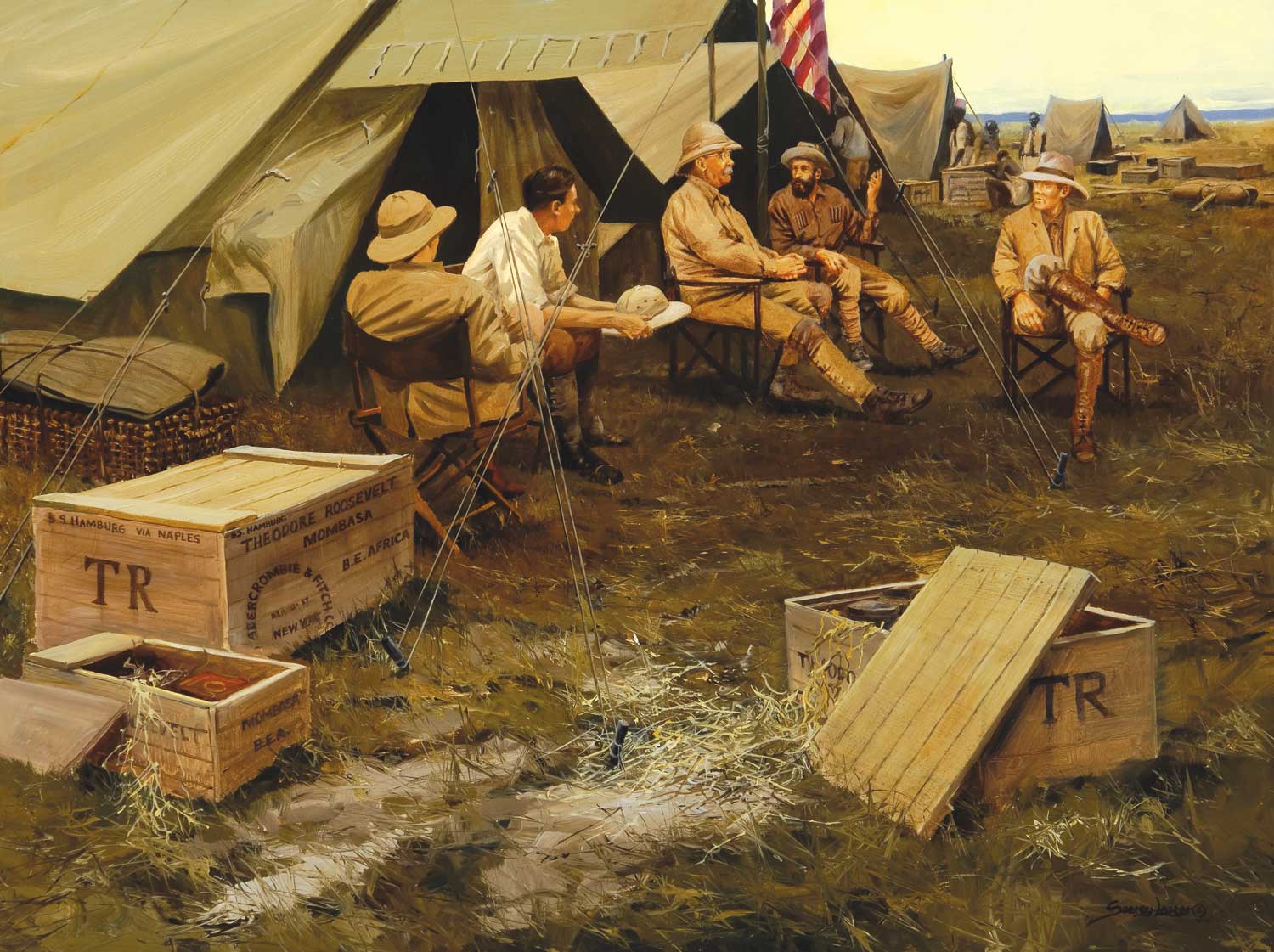

The Arrival by John Seerey-Lester

Next day we shifted camp to a rush-fringed pool by a grove of tall, flat-topped acacias at the foot of a range of low, steep mountains. Before us the plain stretched, and in front of our tents it was dotted by huge candelabra euphorbias. I shot a buck for the table just as we pitched camp.

There were Masai kraals and cattle herds nearby, and tall warriors, pleasant and friendly, strolled among our tents, their huge razor-edged spears tipped with furry caps to protect the points. Kermit was off all day with Tarlton, and killed a magnificent lioness.

In the morning, on some high hills, he obtained a good impala ram, after persevering hours of climbing and running – for only one of the gun-bearers and none of the whites could keep up with him on foot when he went hard.

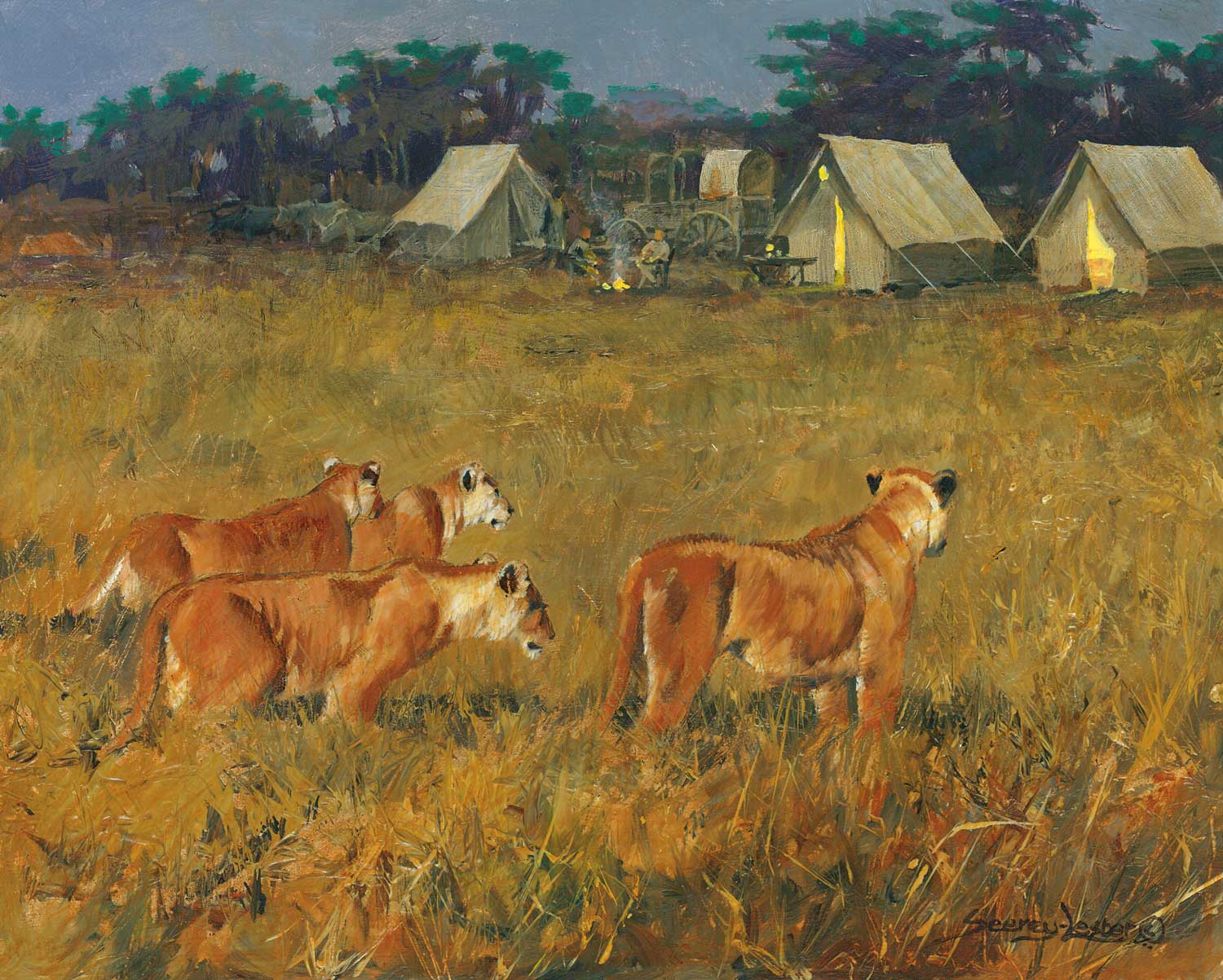

In the afternoon at four he and Tarlton saw the lioness. She was followed by three three-parts-grown young lions, doubtless her cubs, and without any concealment, was walking across the open plain toward a pool by which lay the body of a wildebeest bull she had killed the preceding night. The smaller lions saw the hunters and shrank back, but the old lioness never noticed them until they were within a 150 yards. Then she ran back, but Kermit crumpled her up with his first bullet. He then put another bullet into her, and as she seemed disabled walked up within 50 yards and took some photos. By this time she was recovering, and switching her tail, she gathered her hindquarters under her for a charge; but he stopped her with another bullet, and killed her outright with a fourth.

Sisters at Twilight by John Seerey-Lester

We heard that Mearns and Loring, whom we had left ten days before, had also killed a lioness. A Masai brought in word to the that he had marked her down taking her noonday rest near a kongoni she had killed; and they rode out, and Loring shot her. She charged him savagely; he shot her straight through the heart, and she fell literally at his feet.

The three naturalists were all good shots and were used to all the mishaps and adventures of life in the wilderness. Not only would it have been indeed difficult to find three better men for their particular work – Heller’s work, for instance, with Cuninghame’s help, gave the chief point to our big-game shooting – but it would have been equally difficult to find three better men for any emergency. I could not speak too highly of them; nor indeed of our two other companions, Cuninghame and Tarlton, whose mastery of their own field was as noteworthy as the pre-eminence of the naturalists in their field.

The following morning the headman asked that we get the porters some meat; Tarlton, Kermit and I sallied forth accordingly. The country was very dry, and the game in our immediate neighborhood was not plentiful and was rather shy. I killed three kongoni out of a herd, at from 250 to 390 paces; one topi at 330 paces, and a Roberts’ gazelle at 270. Meanwhile the other two had killed a kongoni and five of the big gazelles; wherever possible the game being hallalled in orthodox fashion by the Mahometans among our attendants, so as to fit it for use by their coreligionists among the porters.

Then we saw some giraffes, and galloped them to see if there was a really big bull in the lot. They had a long start, but Kermit and Tarlton overtook them after a couple of miles, while I pounded along in the rear. However, there was no really good bull, so Kermit and Tarlton pulled up, and we jogged along toward the koppies where two days before I had shot the lioness. I killed a big bustard, a very handsome, striking-looking bird, larger than a turkey, by a rather good shot at 230 yards.

It was now midday, and the heat waves quivered above the brown plain. The mirage hung in the middle distance, and beyond it the bold hills rose like mountains from a lake.

In mid-afternoon we stopped at a little pool to give the men and horses water; and here Kermit’s horse suddenly went dead lame, and we started it back to camp with a couple of men, while Kermit went forward with us on foot as we rode round the base of the first koppies.

After we had gone a mile, loud shouts called our attention to one of the men who had left with the lame horse. He was running back to tell us that they had just seen a big maned lion walking along in the open plain toward the body of a zebra he had killed the night before. Immediately, Tarlton and I galloped in the direction indicated, while the heartbroken Kermit ran after us on foot, so as not to miss the fun, the gun-bearers and syces stringing out behind him.

In a few minutes Tarlton pointed out the lion, a splendid old fellow with a yellow-and-black mane; and after him we went. There was no need to go fast; he was too burly and too savage to run hard, and we were anxious that our hands should be reasonably steady when we shot; all told, the horses, galloping and cantering, did not take us two miles.

The lion stopped and lay down behind a bush. Jumping off, I took a shot at him at 200 yards, but only wounded him slightly in one paw; and after a moment’s sullen hesitation off he went, lashing his tail. We mounted our horses and went after him; Tarlton lost sight of him, but I marked him lying down behind a low grassy ant hill.

Again we dismounted at a distance of 200 yards; Tarlton telling me that now he was sure to charge. In all East Africa there is no man, not even Cuninghame himself, whom I would rather have by me than Tarlton, if in difficulties with a charging lion; on this occasion, however, I am glad to say that his rifle was badly sighted, and shot altogether too low.

Again I knelt and fired, but the mass of hair on the lion made me think he was nearer than he was, and I undershot, inflicting a flesh wound that was neither crippling nor fatal. He was already grunting savagely and tossing his tail erect, with his head held low; and at the shot the great sinewy beast came toward us with the speed of a greyhound.

Tarlton then, very properly, fired, for lion hunting is no child’s play, and it is not good to run risks. Ordinarily it is a very mean thing to experience joy at a friend’s miss, but this was not an ordinary case, and I felt keen delight when the bullet from the badly sighted rifle missed, striking the ground many yards short.

I was sighting carefully, from my knee, and I knew I had the lion all right; for though he galloped at a great pace, he came on steadily – ears laid back and uttering terrific coughing grunts – and there was now no question of making allowance for distance, nor, as he was out in the open, for the fact that he had not before been distinctly visible. The bead of my foresight was exactly on the center of his chest as I pressed the trigger, and the bullet went as true as if the place had been plotted with dividers.

The blow brought him up all standing, and he fell forward on his head. The soft-nosed Winchester bullet had gone straight through the chest as I pressed the trigger, and the bullet went as true as if the place had been plotted with dividers. The blow brought him up all standing, and he fell forward on his head. The soft-nosed Winchester bullet had gone straight through the chest cavity, smashing the lungs and the big blood-vessels of the heart.

Painfully he recovered his feet, and tried to come on, his ferocious courage holding out to the last; but he staggered, and turned from side to side, unable to stand firmly, still less to advance at a faster pace than a walk. He had not ten seconds to live, but it is a sound principle to take no chances with lions.

Tarlton hit him with his second bullet, probably in the shoulder; and with my next shot I broke his neck. I had stopped him when he was still a hundred yards away; and certainly no finer sight could be imagined than that of this great maned lion as he charged.

Kermit gleefully joined us as we walked up to the body; only one of our followers had been able to keep up with him on his two-mile run. He had had a fine view of the charge, from one side, as he ran up, still 300 yards distant; he could see all the muscles play as the lion galloped in, and then everything relax as he fell to the shock of my bullet.

The lion was a big old male, still in his prime. Between uprights his length was nine feet, four inches, and his weight 410 pounds, for he was not fat. We skinned him and started for camp, which we reached after dark.

There was a thunderstorm in the southwest, and in the red sunset that burned behind us the rain clouds turned to many gorgeous hues. Then daylight failed, the clouds cleared, and as we made our way across the formless plain, the half moon hung high overhead, strange stars shone in the brilliant heavens, and the Southern Cross lay radiant above the skyline.

Note: This account is from “Hunting in the Sotik,” a chapter in TR’s African Game Trails, published in 1909 by Charles Scribners’ Sons.