Roosevelt and Cleveland weren’t the only presidents who spent time afield. Here are three U.S. presidents you may not know were avid sportsmen.

Throughout American history, much has been written about the U.S. presidents who were sportsmen—Theodore Roosevelt, Grover Cleveland and Herbert Hoover are often mentioned among them. While historians generally agree that George Washington was an avid horseman and fox hunter, debate persists about whether he was also a wingshooter. Likewise, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson seldom appear on lists of sporting presidents, though there is evidence that, at various stages in their lives, they were both serious bird hunters.

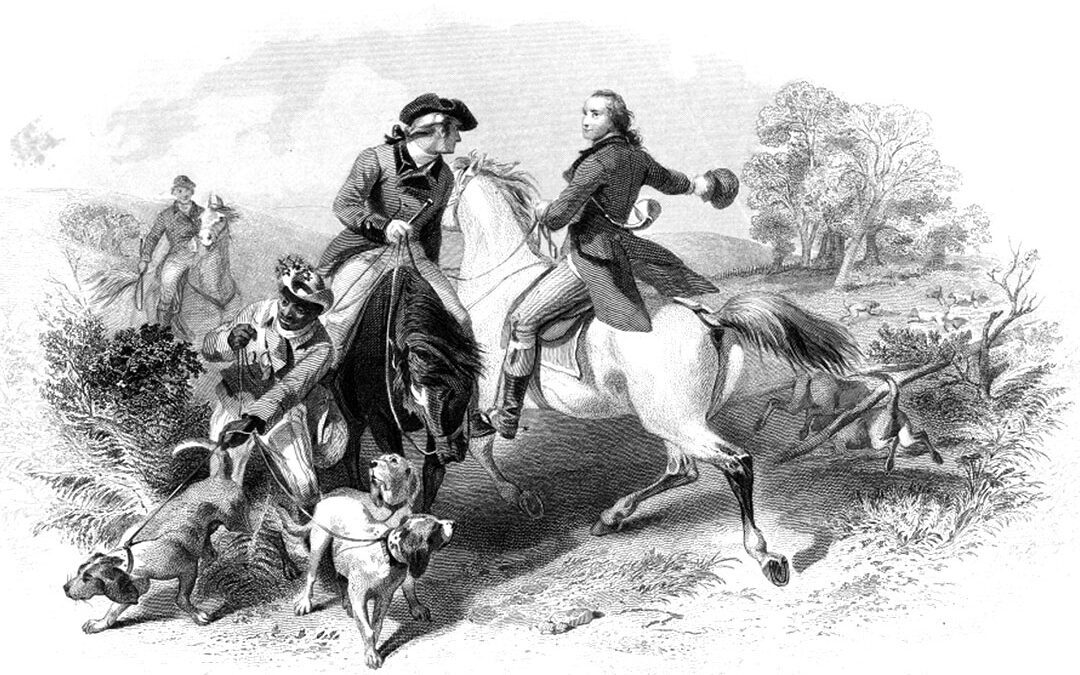

George Washington

Washington was undoubtedly an avid fox hunter; he even bred his own foxhounds. It was clearly his first love for the outdoors, but it was only one facet of his sporting life. He was also a regular wingshooter.

In Washington’s sporting journals, he notes that he often came home with game and once collected as many as eight ducks on an outing. He also mentions duck hunting—“ducking” or “gunning,” as he called it—multiple times, and that on one occasion he hunted waterfowl five days in a row.

In another entry, dated December 23, 1768, he writes that he “went a-pheasant huntg.” However, this reference to “pheasant” is not for the now-common Chinese ringneck—which would not be established in North America for another hundred years—but for ruffed grouse, as it was called at the time.

There is also documentation that Washington purchased “fowling pieces”—the shotguns of his day. On July 20, 1767, he ordered a fowling piece for his stepson, John Parke Custis, who was 14 years old at the time. On another occasion, the president ordered himself a gun, “as handsome a fowling piece 3 feet in Barl. As can be bot. for 3 Guins.”

One of the most overlooked pieces of evidence for Washington being a bird hunter is that he presumably owned bird dogs. While he is well known for breeding foxhounds, he also mentions his “water dog, Pilot,” and his “little spaniel dog, Pompey,” in his journal. Washington never expressly mentions hunting with these dogs, but, given his use of foxhounds, he likely employed Pilot and Pompey during his wingshooting excursions.

Thus, while bird hunting was not Washington’s first love in the outdoors, he more than occasionally participated in wingshooting—it was something he truly enjoyed.

John Adams

While John Adams’ hunting career was briefer than his predecessor’s in office, it was no less significant or intense. When Adams was a child, he was extremely zealous for hunting. In his autobiography, he wrote that during his school-aged years, he loved shooting more than any other pastime or pursuit, including his studies—which worried his parents. While Adams doesn’t explicitly note what animals he hunted during this time, he expresses a fondness for his fowling piece, indicating the gun’s probable use for grouse, waterfowl, heath hens or other small game.

As time went on, Adams relaxed his enthusiasm for hunting and focused his attention on his schoolwork. His scholarly ambitions would eventually lead him to become an attorney, an ambassador to England, a vice president and ultimately the President of the United States. While we lost a hunter from the ranks of history, we gained a true statesman and a proponent of freedom—yet it’s still interesting that his parents worried that he wouldn’t amount to much because of his passion for shooting.

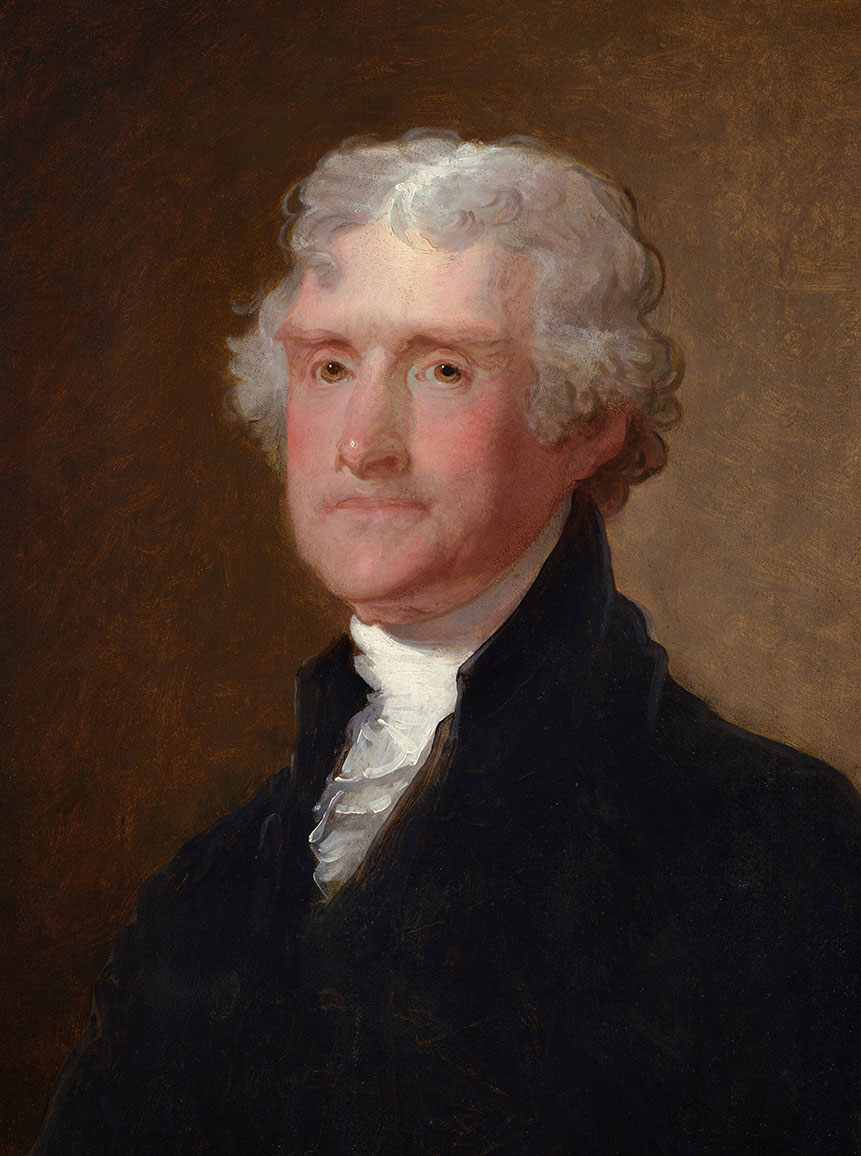

Thomas Jefferson

Most historians don’t consider our third president a hunter. On September 11, 1892, in an article entitled “Presidents as Sportsmen,” The New York Times reports: “To go back to the early presidents, we find them not given to sports, as a general thing. Thomas Jefferson was too busy until he became too old. In his young days, of course, he hunted, for to this day, there is very good shooting at Monticello…”

Contrary to this claim, there are documents that imply Jefferson greatly enjoyed hunting throughout his lifetime. In 1785, he wrote to his 15-year-old nephew Peter Carr about his thoughts on the best form of exercise:

I advise the gun. While this gives a moderate exercise to the body, it gives boldness, enterprise and independence to the mind. Games played with the ball, and others of that nature, are too violent for the body, and stamp no character on the mind. Let your gun, therefore, be the constant companion of your walks.

Likewise, in 1822, toward the end of his life, Jefferson wrote, “I am a great friend to the manly and healthy exercises of the gun.”

There is considerable evidence that much of Jefferson’s hunting was for birds. In Memoirs of a Monticello Slave, Isaac Jefferson, a former slave at Monticello, described Thomas Jefferson as a sportsman, recalling he hunted “squirrels and partridges; kept five or six guns.” As for Jefferson’s sporting ethics, Isaac stated: “Old Master wouldn’t shoot partridges settin. Said ‘he wouldn’t take advantage of ’em’—would give ’em a chance for thar life.” Thus, for Jefferson, hunting was not just about getting meat for the table but for sport.

However, unlike Washington, Jefferson didn’t love dogs—in fact, in a letter dated September 24, 1811, he advocated for their extermination. Obviously, Jefferson had no experience with or appreciation for bird dogs or he may have thought differently, but regardless, it seems that he remained a fan of wingshooting into old age.

As we all know, Washington led the Continental Army to victory, and Adams and Jefferson signed the Declaration of Independence. These three men were undoubtedly instrumental in obtaining the freedoms that we enjoy today, but they were also sportsmen and, to some degree, wingshooters. They hunted not just for food, but also for pleasure. In “Our Hunting Presidents,” Grits Gresham writes that, while Washington became one of the greatest founders of our nation, the true desires of his heart “were his horses and his hounds and to note in his diary that he’d ‘gone a-hunting.’” With this in mind, I can’t help but wonder when the framers wrote about “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness” in the Declaration of Independence if this also included the hunting they so loved.

Read more of Wayment’s work at Upland Ways.

Photos public domain.

There have been few hunters as daring, as powerful, and as articulate as our twenty-sixth president, Theodore Roosevelt. From his ranching years in the Dakota Territory to the famous African adventures, Roosevelt’s tales are unparalleled stories of the hunt. The best of them are collected here.

There have been few hunters as daring, as powerful, and as articulate as our twenty-sixth president, Theodore Roosevelt. From his ranching years in the Dakota Territory to the famous African adventures, Roosevelt’s tales are unparalleled stories of the hunt. The best of them are collected here.

Of Roosevelt’s many volumes of hunting and exploration, two reader favorites have always been Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail and African Game Trails, both excerpted here. During his ranching years, Roosevelt ranged far and wide, and his African trips were also famously bold. In all his expeditions, Roosevelt reveals in detail hunts that were incredible journeys of both pursuit and discovery, for wherever he went in the outdoors he assumed the dual roles of hunter and naturalist. Shop Now