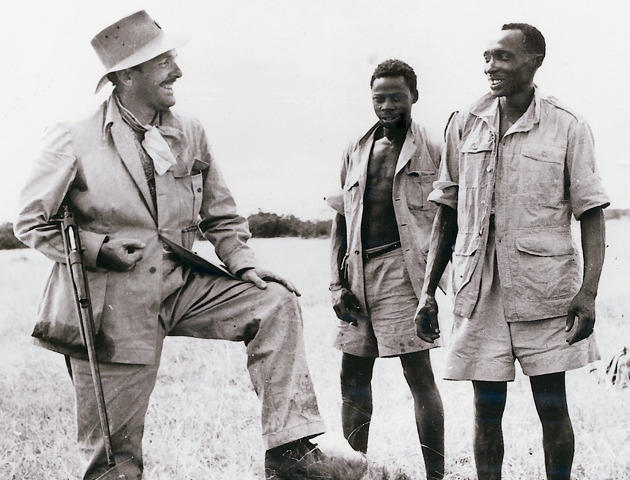

The ruthless Robert Ruark could be a tough and cruel rogue, but he was also considerate, fun-loving and generous to a fault.

Each year about this time, when what my Grandpa Joe variously called “cabin fever” and “the miseries” threaten to reach epidemic proportions, I turn to a time-tested antidote for my doldrums. This involves revisiting The Old Man and the Boy and The Old Man’s Boy Grows Older by Robert Ruark. In my considered opinion, these books represent the finest material ever written on the outdoors.

Originally published as a series of monthly columns in Field & Stream, these tales of a staunch partnership between a young boy and his wise, well-read grandfather revolve around a number of timeless themes. Among them are the pleasures and pitfalls of adolescence; the special family bonds formed with the skipping of a generation; and the manner in which the outdoor experience can mold a man while capturing his soul.

My perspective on Robert Ruark as a writer may be a bit biased, since, like him, I grew up in North Carolina. Yet recently, in the course of casual conversation with First Light Columnist Mike Gaddis, I stated, perhaps a bit brashly, that I considered The Old Man and the Boy the finest piece of outdoor literature ever produced. His response was immediate and direct: “I totally agree.”

With that in mind, I asked participants in an Internet forum for outdoor writers to name their favorite sporting scribes. Predictably, the responses were all over the map, but Ruark ran through them as a consistent thread. There are several reasons why this is the case.

For starters, his “Old Man” stories strike a responsive chord with anyone fortunate enough to have enjoyed a childhood that involved hunting and fishing or who had the privilege of being mentored by a loving grandparent. Similarly, Ruark wrote these pieces from the heart, and even when you give full latitude for literary license, they carry an undeniable ring of authenticity.

In his tributes to the innocence of youth, Ruark frequently mentions the manner in which his immersion in books, along with sessions of what my own grandfather called “dreamin’ and schemin’,” enabled him to take vicarious sporting journeys to distant horizons such as the wilds of India and the game-rich interior of Africa. Once Ruark actually made such journeys and wrote about them, he exhibited an uncanny knack for making readers feel they were his companions in adventure.

Nor should his gregarious nature be overlooked. Most everyone who knew Ruark personally mentions how likable he was and the way his personality lit up a room. He exhibits precisely the same sort of characteristics in the best of his writing. To be sure, in his later years Ruark crawled pretty deeply into the bottle, and our forthcoming biography by his assistant, Alan Ritchie, makes that clear. Yet who can deny it would have been a rare privilege to share a sundowner or a safari with Ruark, and that aspect of the man is a bright thread running through both his writings and his life.

Ruark wrote an article for True Magazine entitled “The Most Unforgettable Sonovabitch I Ever Knew.” Alan Ritchie refers to the story as a “lovely picture of the way Bob remembered his grandfather.” Certainly, Ruark carried on the family tradition, in person and in print, and Ritchie is right on the mark when he styles him the “most incredibly wonderful, generous, humorous and likeable son of a bitch who ever lived.”

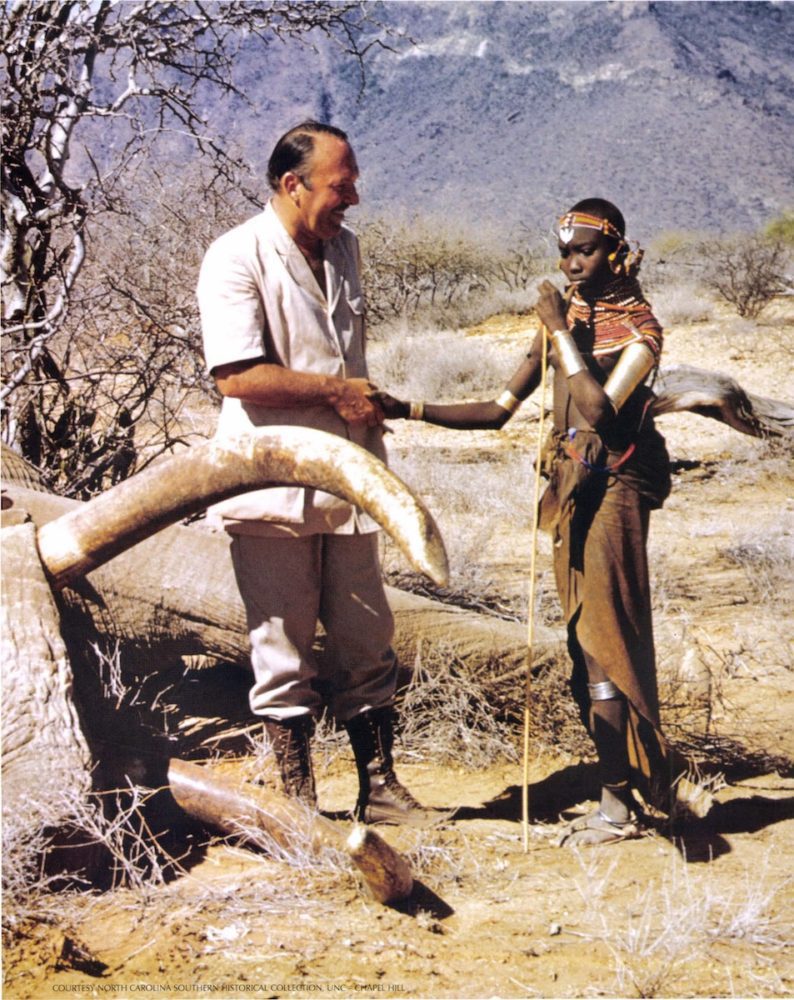

Ruark extends thanks to a Samburu girl who led him to his last elephant on his hunt in the Northern frontier district in Kenya.

Ruark’s career falls pretty clearly into four distinct phases—his boyhood and college years, his early career working with newspapers and his military service in World War II, his breakthrough as a newspaper columnist of national stature, and his final twelve years beginning with his first African safari in 1953. This last phase coincided almost exactly with the period Alan Ritchie served as his secretary. The coincidence was a fortuitous one. These were some of the most interesting and productive years of Robert Ruark’s life, and Ritchie devotes the bulk of his biography to them.

Still, Ritchie provides ample coverage and insight into every aspect of Ruark’s fifty years. His childhood was both difficult and delightful. Even his love of the “Old Man” (actually a composite of both grandfathers and some of the “honorary uncles” to whom he dedicated The Old Man and the Boy) and frequent escapes into the wild could not entirely offset the problems posed by troubled parents—one was an alcoholic, the other a drug addict. Then there were Ruark’s precociousness, his bookworm tendencies, small size, misanthropy and absence of close friends anywhere near his age—all of which made him a boyhood target of bullies.

When the Depression ate deeply into the modest fortunes of Robert Ruark’s family, and when his paternal grandfather died just before he completed high school, things looked bleak indeed. Somehow, though, he managed to scrape and scrap his way through college at Chapel Hill, and those four years saw a lot of “growing up,” not to mention stints as varied as fraternity bootlegger and campus newspaper cartoonist. Small wonder he was drunk at commencement and roaring drunk by the time he and some companions were arrested a few hours later. Ritchie shares this episode in a fashion which leaves little doubt that Ruark relished telling about the incident.

The transition from college boy to journalist was an interesting, challenging one, but clearly by the time he entered the military in World War II, Ruark had a pretty good feel for his future. While in the Merchant Marine, he saw dangerous duty in the North Atlantic and Mediterranean followed by a delightful tour in Australia. Soon after the war he was well on his way to bigger, better things, as is evidenced by the many articles he sold to major magazines.

Ruark returned home from the war, as Ritchie puts it, “having decided to look for the biggest stone to throw at the biggest glass house.” Ruark found plenty of rocks, and he shattered glass with abandon in stories that were satirical, scathing, sexist and often scurrilous. Nothing seemed sacred. He ridiculed American women (though he was married), managed to offend Frank Sinatra and Mafia mobster “Lucky Luciano,” created a storm of controversy with investigations into the inappropriate conduct of Lt. Gen. John C. H. Lee as head of American forces in post-war Italy, and in general made a big splash. Soon, he was one of the country’s most popular and widely read newspaper columnists, offering daily doses of what he called “belt-level journalism” aimed at the common man. He churned out five columns a week, year after year, along with magazine articles and several decidedly forgettable books.

Ruark soon became a “personality,” with a penthouse suite in a tony district of New York. He was a regular at the city’s ritziest drinking and dining spots and earned impressive amounts of money, but increasingly, he was miserable. That misery, combined with his first African safari, proved to be a watershed in his life and career and life. It produced a move to Spain, which Robert Ruark called home for the rest of his days; his book, Horn of the Hunter (written in a month!); and a love affair with Africa. It was also the time when Ruark hired Alan Ritchie.

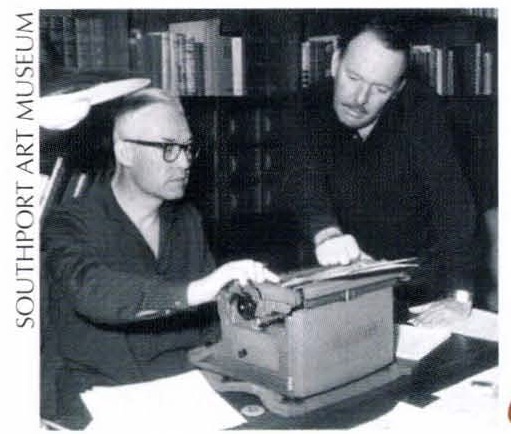

Alan Ritchie served as Ruark’s personal secretary for 12 years.

For the next twelve years, until Robert Ruark’s death in 1965, he and Ritchie worked together in what was in many ways an ideal partnership. It was during this period that Ruark wrote “The Old Man and the Boy” column, and from those pieces came The Old Man and the Boy and The Old Man’s Boy Grows Older (although not all of them appear in the books). He wrote his blockbuster novel, Something of Value, along with several other successful works of fiction including Uhuru, The Honey Badger and Poor No More with its intense autobiographical overtones. There were also regular contributions to True, Playboy, Esquire and The Saturday Evening Post.

Ritchie’s account provides detailed insight into almost every aspect of Robert Ruark. We learn, for example, that “on a full book-writing day, a normal production for Bob would be twenty pages—some six thousand words.” We see inside his tempestuous, often troubled marriage, and there is considerable information on Bob and Ginny Ruark’s personal lives. Ginny was “a most excellent critic” when appraising her husband’s work, and for many years she stoically tolerated his infidelities. Only in the final years, when drink dominated so much of Ruark’s life, did the marriage dissolve.

One of the most engaging facets of Ritchie’s treatment involves his safaris with Robert Ruark, who once described Africa as “the place where I met God.” The Dark Continent provided subject matter for his finest novels and dozens of magazine articles. Ritchie delineates all this and much more—the peaceful nature of life at Palamos and its sharp contrasts with interludes of globetrotting; the never-failing stimulation provided by safari and shikar; Robert Ruark’s approach to writing; the inspiration he found when surrounded by his trophies and guns; his ongoing problems with editors and even his devoted literary agent, Harold Matson; and other all-too-human shortcomings. Throughout the text, we are constantly reminded of the manner in which Ruark squeezed every drop of pleasure from the sponge of life.

Ritchie’s biography includes much sadness. We follow Robert Ruark as he deteriorates into a besotted, bewildered state, when he could not write without copious amounts of liquor, and when he stops writing newspaper columns, which had been a mainstay earlier in his career. Ritchie speaks from the heart when he says: “Towards the end I lost him to some extent in a confused haze of alcohol and women.”

Ritchie pointedly describes Robert Ruark’s bad sides: “A rogue with the women and the liquor and his general plan of living; hard and tough and even cruel in his relationships with many people; often ruthless in reporting and column writing.”

Set against these shortcomings is the man he found to be “kind and considerate so many times; industrious and hardworking; fun loving; humorous; generous to a fault; always quick to give a handout to a person less fortunate than himself; loved by many and a good friend of his friends; and a man who gave millions of people throughout the world many good hours of reading pleasure.”

Ruark once confided to a friend. “I started out to be a man…glad, sad, occasionally triumphant.” Posterity differs on whether his life was essentially tragic or one dominated by triumph. In Ritchie’s view, “on the balance, the scales were well loaded in his favor.” I happen to concur even while recognizing that Ruark was an incorrigible chauvinist, a hopeless alcoholic who violated almost all the dictums for life the Old Man set before him, and in many ways a miserable human being. Whatever your personal view of Robert Ruark, Ritchie’s powerful, poignant biography will give you pause to ponder even as you read a life’s tale filled with wonder.

This timeless classic, originally published in 1957 and never out of print, tells the story of a remarkable friendship between a young boy and his grandfather. The Old Man and the boy hunt the woods and fields of North Carolina together; they fish the lakes, ponds, and sea. All the while the Old Man acts as teacher and guide, passing on his wisdom and life experiences to his grandson, who listens in rapt fascination.

This timeless classic, originally published in 1957 and never out of print, tells the story of a remarkable friendship between a young boy and his grandfather. The Old Man and the boy hunt the woods and fields of North Carolina together; they fish the lakes, ponds, and sea. All the while the Old Man acts as teacher and guide, passing on his wisdom and life experiences to his grandson, who listens in rapt fascination.

In Ruark’s skillful hands, the book becomes much more than a boy’s early lessons in hunting, fishing and camping. It is a heartwarming, eloquent and ultimately poignant tale about choices, about responsibility and about becoming a man. Buy Now