Shocked and angered by his friend’s horrible death, the old trapper was determined to get revenge.

Almost every trapper past middle age who has spent his life in the wilderness has stories to tell about exceptionally savage bears.

One of these stories was told in my ranch house one evening by an old mountain hunter, clad in fur cap, buckskin hunting shirt, and leather trousers, who had come to my ranch at nightfall when the cowboys were returning from a day’s labor.

The old fellow, who was known by the nickname of “Buckskin,” had camped for several months in the Bad Lands but a score of miles away from my ranch. Most of his previous Me had been spent among the main chains of the Rockies. After supper the conversation drifted to bears, always a favorite subject in frontier cabins, and some of my men began to recount their own adventures with these great, clumsy-looking beasts.

This at once aroused the trapper’s interest. He soon had the conversation to himself, telling story after story of the beasts he had killed and the escapes he had made in battling against them. In particular he told us of one bear, which many years before had killed his partner while they were trapping.

The two men were camped in a high mountain valley in northwestern Wyoming, their camp being pitched at the edge of a “park country,” a region of large glades and groves of tall evergreen trees.

They bad been trapping beaver, which on account of its abundance and the value of its fur, was more eagerly followed than any other by the old-time plains and mountain trappers. They had with them four shaggy pack ponies, such as most of these hunters use, and as these ponies were not needed at the moment, they had been turned loose to shift for themselves in the open glade country.

Late one morning three of the ponies surprised the trappers by galloping up to the campfire and there halting. The fourth did not make his appearance. The trappers knew some wild beast must have assailed the animals, and had probably caught one and caused the others to flee toward the place where they learned to associate with safety.

Before dawn the next morning the two men started off to look for the lost horse. They skirted several great glades, following the tracks of the parties that had come to the fire the previous evening. Two miles away, at the edge of a tall pine woods, they found the body of the lost horse, already partially eaten.

The tracks round about showed that the assailant was a grizzly of uncommon size, which had evidently jumped the horses just after dusk, as they fed up to the edge of the woods. The owner of the horse decided to wait by the carcass for the bear’s return, while old Buckskin went off to do the day’s work in looking after the traps and the like. Buckskin was absent all day, and reached camp after nightfall. His friend had come in ahead of him, having waited in vain for the bear. As there was no moon, he had not thought it worthwhile to stay by the bait during the night.

The next morning, they returned to the carcass and found that the bear had returned and eaten his fill, after which he lumbered off up the hillside. They took up his tracks and followed him for some three hours, but the wary old brute was not to be surprised. When they at last reached the spot where he had made his bed, it was only to find that he must have heard them as they approached, for he evidently left in a great hurry.

After following the roused animal for some distance, they found they could not overtake him. He was in an ugly mood and kept halting every mile or so to walk to and fro, bite and break down the saplings, and paw the earth and dead logs. But in spite of this bullying, he would not absolutely await their approach, but always shambled off before they came in sight.

At last, they decided to abandon the pursuit. They then separated, each to make an afternoon’s hunt and return to camp by his own way.

Our friend reached camp at dusk, but his partner did not turn up that evening at all. However, it was nothing unusual for either one of the two to be off for a night, and Buckskin thought little of it.

Next morning, he again hunted all day and returned to camp fully expecting to see his friend there but found no sign of him. The second night passed, still without his coming in.

The morning after, the old fellow became quite uneasy and started to hunt him up. All that day he searched in vain, and when, on coming back to camp there was still no trace of him, he was sure that some accident had happened.

The next morning, he went back to the pine grove where they had separated on leaving the trail of the bear. His friend had worn hobnail boots instead of moccasins, which made it much easier to follow his tracks. With some difficulty, the old hunter traced him for some four miles, until he came to a rocky stretch of country where all sign of the footprints disappeared.

However, he was a little startled to observe footprints of a different sort. A great bear, without doubt the same one that had killed the horse, had been traveling in a course parallel to that of the man.

Apparently, the beast had been lurking just in front of his two pursuers the day they followed him from the carcass, and from the character of the “sign,” Buckskin judged that as soon as he had separated from his friend, the bear had likewise turned and had begun to follow the trapper.

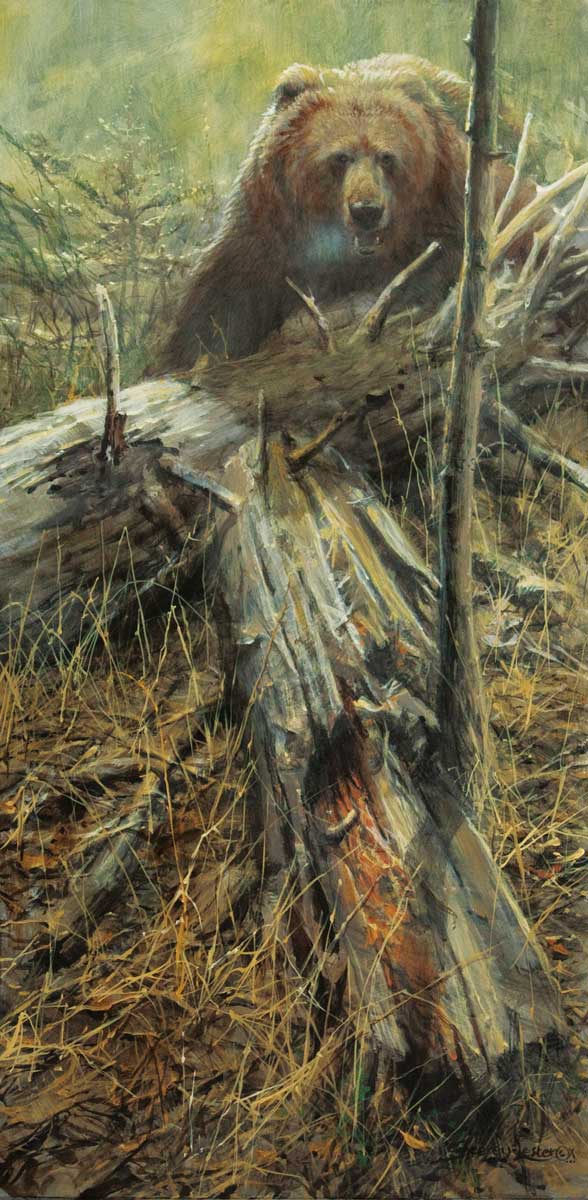

Dead Fall by John Seerey-Lester

The bear had not followed the man into a rocky piece of ground, and when the old hunter failed in his efforts to trace up his friend, he took up the trail of the bear instead.

Three-quarters of a mile on, the bear, which had so far been walking, broke into a gallop, the claws making deep scratches here and there in the patches of soft earth. The trail then led into a very dark woods, and here the footprints of the man suddenly reappeared.

For some little time, the old hunter was unable to make up his mind with certainty as to which one was following the other but finally, in the decayed mold by a rotten log, he found unmistakable sign where the print of the bear’s foot overlaid that of a man. This put the matter beyond doubt. The bear was following the man.

For a couple of hours more, the hunter slowly and with difficulty followed the dim trail.

The bear had apparently not cared to close in, but had slouched along some distance behind the man. Then in a marshy thicket where a mountain stream came down, the end had come.

Evidently at this place the man, still unconscious that he was followed, had turned and gone upward, and the bear, altering his course to an oblique angle, had intercepted him, making his rush just as he came through a patch of low willows. The body of the man lay under the willow branches beside the brook, terribly torn and disfigured.

Evidently the bear had rushed at him so quickly that he could not fire his gun and had killed him with its powerful jaws. The unfortunate man’s body was almost torn to pieces. The killing had evidently been done purely for malice, for the remains were uneaten, nor had the bear returned to them.

Angry and horrified at his friend’s fate, old Buckskin spent the next two days looking carefully through the neighboring groves for fresh tracks of the cunning and savage monster. At last, he found an open spot of ground where the brute was evidently fond of sunning himself in the early morning, and to this spot the hunter returned before dawn the following day.

He did not have long to wait. By sunrise a slight crackling of the thick undergrowth told him the bear was approaching. A few minutes afterward the brute appeared. It was a large beast with a poor coat, its head scarred by teeth and claw marks gained in many a combat with others of its own kind.

It came boldly into the opening and lay down, but for some time kept turning its head from side to side so that no shot could be obtained.

At last, growing impatient, the hunter broke a stick. Instantly the bear swung his head around sidewise, and in another moment a bullet crashed into its skull at the base of the ear, and the huge body fell limply over on its side, lifeless.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 2015 September/October issue of Sporting Classics. “A Man-Killing Bear” is from The Best Hunting Stories Ever Told, edited by Jay Cassell and released by Skyhorse Publishing in 2010.

In Ranch Life and the Hunting-Trail, Roosevelt records his experiences from his hunting adventures, the people and animals that he encounters, the excitement of the round up, to the everyday life on the ranch. TR’s delightful prose provides a straightforward and very entertaining read. The book is handsomely illustrated with 95 pen and ink drawings by the premier western artist of the time, Frederic Remington. Buy Now

In Ranch Life and the Hunting-Trail, Roosevelt records his experiences from his hunting adventures, the people and animals that he encounters, the excitement of the round up, to the everyday life on the ranch. TR’s delightful prose provides a straightforward and very entertaining read. The book is handsomely illustrated with 95 pen and ink drawings by the premier western artist of the time, Frederic Remington. Buy Now