Daddy sent Theodore off to Harvard in 1876 with this advice: “Take care of your morals first, your health second, and your studies third.”

Predictably, young Roosevelt was a better boxer than student, much preferring independent inquiries rather than activities prescribed by curriculum. He kept his rifle and hunting clothes in his room and made frequent forays into the Maine woods. Refusing to work under faculty supervision, he researched and wrote his first book, A Naval History of the War of 1812. He changed his major from natural science to history and government, but still managed to graduate cum laude in 1880.

Meanwhile, he met and courted Alice Hathaway Lee. But he had these God-awful red mutton-chop sideburns. He was just too bombastic, a flamboyant dresser, and quick to throw a punch. Alice turned him down, at first.

“You see that girl,” he bragged to a classmate, “she won’t have me, but I am going to have her.”

When Alice finally consented, Theodore ordered a pair of French dueling pistols to defend his claim and her honor. He had one hell of a time getting them through Customs. They were married on his 22nd birthday, Oct. 27, 1880. Theodore entered Columbia law school, but found it so boring he quit after one semester, ran for the New York State Legislature and was elected to the first of three terms.

There were two breeds of Republicans in those days. The first were closely allied with the Captains of Industry—Vanderbilt, Carnegie, Morgan, Rockefeller—“the wealthier criminal class,” Roosevelt called them. The second were reformers who believed the Constitutional power to regulate interstate commerce could create a better life for all citizens. Roosevelt the reformer, whose energy and enthusiasm had already made him known as “a locomotive in human pants,” soon ran afoul of party bosses with close establishment ties.

Roosevelt was at his desk in legislative session when a messenger brought a telegram. “Baby girl. Mother and child doing well.” But another followed. His mother was gravely ill with typhoid fever. He rushed home, where his mother died in his arms. Then came a call from an upstairs bedroom. Just a few hours after delivery, his wife’s kidneys shut down. Ten hours later, his dear Alice died in his arms as well. And he lost them both on Valentine’s Day 1884.

“The light has gone out of my life,” he said. His family watched him stagger and stumble around the double funeral. They were afraid he might kill himself, but he did not. He left his infant daughter in his sister’s care and lit out for the Dakota Territory.

Roosevelt had been there before on a buffalo hunt. The stark beauty of the country had so impressed him, he bought 450 stock cows and hired two men to run them. Now he would run them himself.

“I have always said I would not have been president had it not been for my experience in North Dakota, for it was there that the romance of my life began . . . There were all kinds of things of which I was afraid at first, ranging from grizzly bears, mean horses, and gunfighters; but by acting if I were not afraid, I gradually ceased to be afraid.”

It was wild country, alright, absolutely no fences. General Sherman said the Badlands looked like hell with the fires burned out. He was more right than he knew. The Little Missouri cut through lignite coal veins and lightning strikes set them afire. They were still burning when Roosevelt saw them and they are burning today, 50,000 years after they first lit up.

Buttes, canyons, coulees, draws, shelter from the winter wind, water running from the rocks and the bluestem and buffalo grass grew stirrup high everywhere. A perfect place to winter cattle, and America was hungry for beef. Roosevelt drew on his inheritance and bought additional cows in several installments, pastured them on two spreads, the Maltese Cross and the Elkhorn.

Elkhorn Ranch in Dakota Territory cerca 1884.

“My home ranch lies on both sides of the Little Missouri,” he wrote of the Elkhorn. “The nearest ranch above me being about twelve, and the nearest below me about ten miles distant. The story-high house of hewn logs is clean and neat with many rooms, so that one can be alone if one wishes to. The house is situated where the summer sun never hits the porch and one may enjoy a smoke in a rocking chair. Rough board shelves hold a number of books, without which some of the evenings would be long indeed.”

Roosevelt, already an accomplished horseman, took right to the cowboy life, though his ranch hands noted he never mastered the lariat. He wore silver spurs, chaps, a slouch hat, a handmade buckskin outfit, a skinning blade from Tiffany’s, and a lavishly engraved .45 Colt Peacemaker. But he worked daylight to dark— “can’t-see to can’t-see”—right alongside his men. He kicked together driftwood fires and slept on the ground and was covered with dirt, soot and plastered with manure at branding time. He arrested desperadoes at gunpoint and hauled them to justice.

He had an 1876 Winchester lever gun in .45-75 for hunting in the mountains, a tight-choked 10-bore hammer shotgun for ducks and geese, an open-choked 12 for grouse. When just knocking around, he kept an over-under 16-bore and .45-70 combination gun close to hand in his saddle scabbard. He kept himself, his hands and neighbors well supplied with game and was appointed to the local cattleman’s association. He volunteered for vigilante posse duty, but was turned down as “his face was too well known.”

But there was big trouble coming. The white man had been in the Badlands only a few dozen years, too short a time to fully gauge the potential of Dakota weather, which can be ruthless in the extreme. The summer of 1886 was dry, the high ground pastures played out early, and there was no hay to be made. Indeed, there was scant machinery to even make hay. Ranchers had never needed hay before, as the cattle wintered just fine in the grassy coulees, draws and gulches. When the moisture finally came, it was snow, not rain.

Cowmen in the Badlands still speak of it today, “the Great Die Off.” One blizzard after another buried what was left of the grazing land, and cattle were found frozen to death where they stood at minus 40. Tougher animals survived long enough to eat the tarpaper off ranch houses. Others were found dead in cottonwood trees along the river bottoms after the snow melted, having climbed massive snowdrifts to reach edible twigs before expiring 20 feet off the ground. Tens of thousands of cattle died, around 80 percent of the herd.

“If you could kick the person in the pants responsible for most of your trouble,” Roosevelt later wrote, “you wouldn’t sit for a month.”

Roosevelt lost a million in today’s money, almost half his net worth. And he did not sit down; he fled back East, got to know his young daughter, married a childhood friend, Edith Kermit Carow, ran for mayor of New York City and lost. But this was not the man New Yorkers knew before.

“His voice which would not even raise an echo in Albany,” one reporter noted, “is now strong enough to drive oxen.”

His cowhands remained in the Badlands. Peering through their frosted windows. If they saw a hump of snow, they reckoned there was a dead cow beneath it. A shovel and an axe was all they needed, and they ate right well till spring.

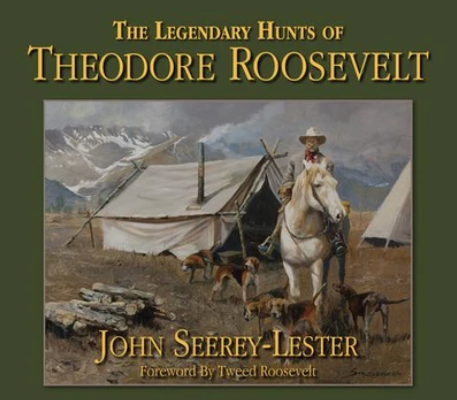

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now