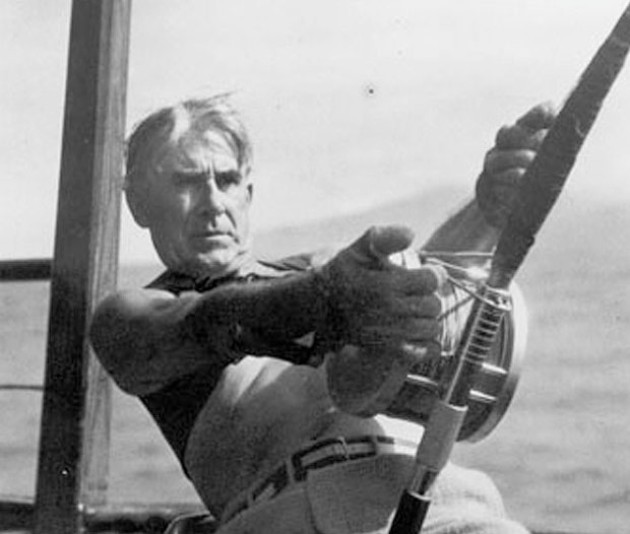

The year was 1909 in America and a young, green scientist stepped boldly from a stage on the campus of Yale University, his hard-earned Master of Science degree firmly in his grasp. Now, he was a forester! Bonafide, certified and anxious. The university had captioned his yearbook photo with his personal motto, “To Hell with Convention.” Little did anyone know at the time that Burlington, Iowa born Aldo Leopold had been released upon the land!

Leopold would start his career as a forester with the U. S. Forest Service, assigned to the Arizona/New Mexico territory in 1912. During his dozen years there he began to envision the land as a living organism and its inhabitants as part of the whole, all interdependent. He called his theory the “community concept.”

By 1924 Leopold had transferred to Madison, Wisconsin, to become associate director of the U. S. Forest Products Laboratory, an affiliate of the university. He added to his duties later by teaching land and game management at the university in 1928, and tested his new land ethic theory at every turn. By 1933 Aldo Leopold had become chairman of the Department of Game Management, University of Wisconsin, the first major school to establish such a curriculum.

Leopold wrote a textbook on this new field, Game Management, (published in 1933) that has become a classic. His accomplishments in conservation education and research, his myriad scientific papers, popular books, and his keen observations of the natural world are now legend.

Leopold is best known and remembered by millions of people around the world for his book, A Sand County Almanac, published one year after his death in 1948. Sand County is often acclaimed by readers as a conservation masterpiece.

A far different pathway to notoriety in the field of game management was taken by a man who became one of Leopold’s dearest friends.

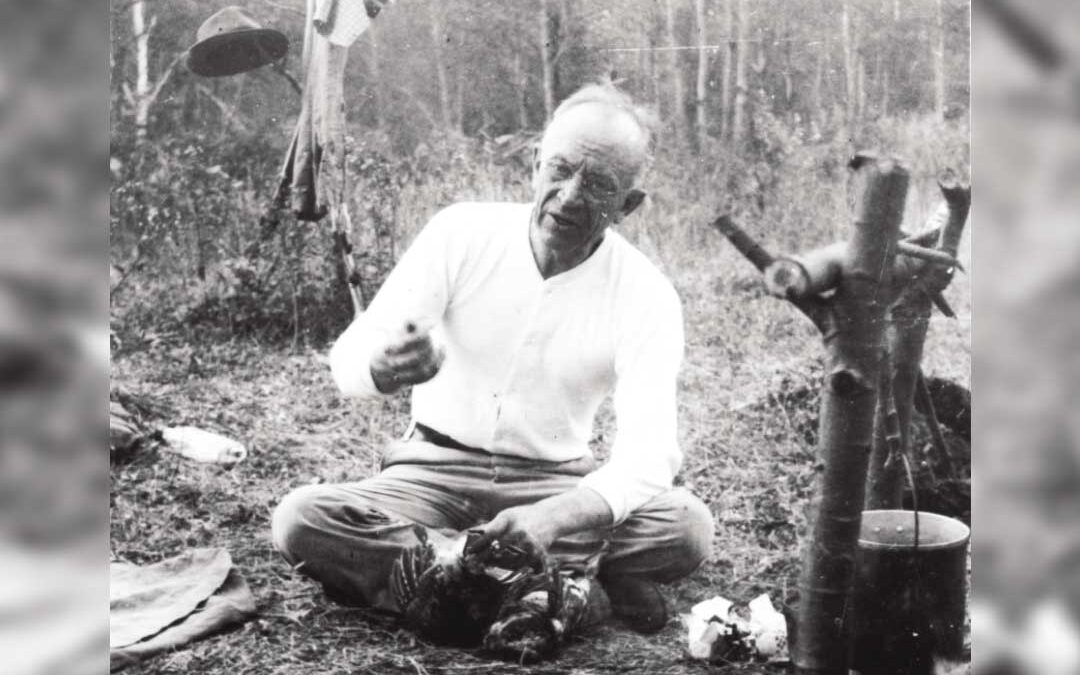

Herbert L. Stoddard, a native of Rockford, Illinois, dropped out of high school in 1905 to work his grandfather’s farm near Prairie du Sac, Wisconsin, where he became enamored with the wild animals he encountered. By 1910 he was a full-time, practicing taxidermist, first in Milwaukee and later at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History.

Stoddard immersed himself in learning the natural history of his museum subjects and logged many hours studying what little was known about wild animal life cycles and habits. He became a self-taught naturalist in spite of the absence of literature on such subjects and, after 14 years of taxidermy and independent study, he began to get noticed by his peers.

Stoddard was offered a new job in 1924, a dream job to a hard-working museum employee. He would become the principal investigator of a research project to study the decline of bobwhite quail in southwest Georgia. Initiated by wealthy members of a sportsmen’s club called the Links Club-New York City, in collaboration with the U. S. Biological Survey (later to become the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service), the study would investigate quail habitat and life histories. It was right down Stoddard’s alley.

By 1931 Stoddard had completed his studies. The product of his efforts was his classic text on quail management, The Bobwhite Quail: Its Habits, Preservation, and Increase. In his book he outlined a completely new way of managing quail and other game animals. He argued that wildlife populations could be sustained and even increased by the active management of natural processes such as fire. Although controversial at first, the use of “prescribed burns” proved its value time and time again in the piney woods of south Georgia and has since been used successfully in many other states and countries.

Stoddard published his quail management book in 1931; Leopold published his text on game management in 1933. The two conservation leaders, traveling different paths, were now joined by their common interests in wildlife conservation and set the stage, through their prolific research publications, for an era of scientific inquiry into managing America’s natural resources.

But wait! These two icons of conservation had more than a love of wildlife in common. The ankle deep, curled, wood shavings on the floor of Leopold’s workshop portended another common interest – archery!

Stoddard’s quail study area, a 1000-acre plantation in Grady County, Georgia, was aptly named “Sherwood.”

Both men enjoyed making, shooting and exchanging bows and arrows. They were known to hunt with their homemade weapons and to “punch the paper” on an occasion.

The following letter from Aldo to Herbert leaves no doubt how Leopold feels when he draws that first shaving of Osage off the billet. The knife frees layer upon layer of wood with each draw, wood that shields the mystical innards of the post. Will it produce a dud or a life-long companion?

Note: The author wishes to thank Gene Kelly of Columbia, Missouri for sharing his copy of Aldo Leopold’s letter.

March 26, 1934

Dear Herbert,

I am sending you by express, a yew bow, which I have been making for you this winter. I have enjoyed the task because it was a way to express my affection and regard for one of the few individuals who understands what yew bows are all about – along with quail and mallards and wind and sunsets.

I cannot assure you that it is a good piece of wood. Staves, like friends, have to be lived with in many woods and weathers before one knows their quality. The fact that the stave is yew, has a specific gravity of .432, came from Roseburg, Oregon, and has been waiting for a job since 1930, is no test of how it will soar an arrow. These facts guarantee nothing. Nor does the zest with which the bowyer expends his powers in sculpting the log, promise the birth of a life-long companion.

All I can say about this bow is that its exterior “education” embodies whatever craft and wisdom has been mine to impart with the carving. What lies inside, however, is the everlasting question.

The bow is built for endurance rather than speed, hence the length. Its weight (in my cold cellar) is 50 pounds at 28 inches. This ought to temper down, in your climate, to a heavy American or light York. I doubt if it will hold on the gold at 100 yards, but it might. Should you use it regularly for York, I would advise a lighter string.

If it proves a good piece of wood, it should be re-tillered after a season’s use, to catch up any “hinge” which may by then have developed. I will be glad to do this for you. At that time, should it have proven a worthy stick, it may also be shortened to make a straight hunter, or a York.

I have tried to build into this bow the main recent improvements in bow design – but since some of them are not visible, they will bear mention. The square cross section and waisted handle are of course visible improvements, but probably less important than the new location of the geographic center. In former days this was put close under the arrow plate, but in this bow it lies as near the center of the handle as is possible without overworking the lower limb. In bows I’ve made with a 3 ½-inch handle I have found longevity. But I know from observation, Herbert, that these modern bows never appear at two successive annual tournaments, or if they do, they are on “crutches” and ready for premature pensioning to some idle peg on the bow rack. Let’s see where this one ends up.

The horns whence came these limb nocks were pulled off the skeleton of an old cow on the Santa Rita range of New Mexico by Dave Gorsuch. The slight flaws at the base of the upper nock are the measure of the seasons which bleached her bones before Dave found her. I have no doubt that many a black vulture perched on her skull meanwhile, and many a quail and roadrunner, coyote and jackrabbit played their little games of life and death in the hackberry bush hard by her withering hide. Question. Did that stogy old cow, whilst living, know, or get any satisfaction from knowing, that in grazing the scrubby brush and high mountain meadows she was converting the earth’s chemistry into limb nocks for our bow? For that matter, does a yew tree glory in fashioning from mere soil and sunlight a wood whose shavings curl in ecstasy at the prospect of becoming a bow? Does a cedar’s pride lie in his towering height, or in the fact – unknown to all save archers – that under his shaggy bark lies a snow-white wood that planes with the joyful sound of tearing silk – or the joyful sound that bluebills make when they hurdle out of the sky at the invitation of placid water?

These are questions meant for an archer to ask – but for no man to answer.

One cannot fashion a stave without indulging in fond hopes of its future. I hope that one day this one will sire a litter of six golds for you, and will many a time hear your gleeful chuckle as you add up the ends for a 500 score. On many a thirsty noon I hope you lean it against a mossy bank by cool springs. In fall, I hope its shafts will sing in sunny glades where turkeys dwell, and that one day, Herbert, one day some wily buck will live just long enough to startle at the twang of its speeding string.

Among my more homely prayers are these: That the limb nock will never come off just as you start out of the house for the woods or targets; nor the arrow plate spring loose just as you modestly explain to some visiting tyro that the inlay is made of mastodon ivory which has stayed put since the Pleistocene, well, until now.

And lastly, my dear Herbert, if the bow breaks, with or without provocation, pray waste no words or thoughts in vain regret. There are more staves in the woods that have not yet sped an arrow, all longing to realize their manifest destiny. Just blow three blasts on your horn and I will make you another.

Yours as ever,

Aldo Leopold

Herbert L. Stoddard on Aldo Leopold

He had a stimulating personality; in conversation he was able to draw out the thoughts of others, as well as freely sharing the depths of his own brilliant mind. He would think deeply and quietly a few moments, marshalling his thoughts in logical sequence, and then express them clearly, forcefully and eloquently.

Later, I was to find him an ideal chairman for any sort of conservation meeting because of his extraordinary ability to grasp the basic aspects of the situation, discarding unimportant side issues and argumentative froth and presenting the fundamental points in a few choice phrases.

Note: From Memoirs of a Naturalist, University of Oklahoma Press. 1969:218.