One of the first duck hunters I met when I moved to the coast of Georgia in 1968 was a game warden named Dick McIntyre. He lived just a hop and a jump across the Savannah River in Beaufort, South Carolina. And no, I didn’t meet him because I was guilty of some game violation, but through our mutual interest in old duck decoys.

Dick’s son, Cameron McIntyre, was born that same year. I well remember him at age three and four dragging an old wooden duck around the yard. His love for all things waterfowl grew stronger with each passing year and that, combined with his artistic talent and drive, has placed him front and center for many years now as an artist in that genre.

Specklebellied geese, still life, life size, white pine and oil.

As a very young child, Cameron accompanied his father on many pre-dawn outings for ducks. They mostly hunted in the marshes of Wimbee Creek, a tributary of the Combahee River. When the adjacent plantations would hunt their water-controlled impoundments, the ducks would all spill out into the surrounding public marshes. Many great hunts for black ducks, mallards, teal, widgeon and gadwalls were enjoyed there.

I asked his father for his thoughts on Cameron’s initiation into the world of waterfowl and his chosen career in that venue.

“Cameron made his first voyage into the Lowcountry saltmarsh before he could speak in sentences. He was absolutely overtaken by the whole waterfowling scenario. In elementary school his teachers sent notes home in reference to his constant doodling of ducks and geese. His artistic accomplishments are certainly a result of his never ending focus on what he absorbs in nature. Cameron sees things in a different light than most. His carvings and paintings are reflective of the mind of an artist who not only portrays his subjects, but loves them. His artistic legacy will be admired by those who love the natural world, for generations.”

Cameron couldn’t get enough of it. At age eight in 1976 he shot his first duck, a green wing teal. In high school he built a sneak boat and spent nights alone in the river marshes listening to the teal whistling, mallards quacking and pintails ripping the air with their pinions as they passed overhead. This devotion to all places wild where waterfowl frequent has only increased every year of his life.

Preening gadwall, hollow cedar and oil.

His father was a dealer as well as a collector of decoys. On one occasion he brought home a trunk full of assorted old birds that he purchased from a Maryland collector, Bobby Richardson. Although only nine years old, Cameron was fascinated by the form and colors of those birds. It became obvious to everyone that the innate artistic talent laden in his genes was rapidly emerging with a strong focus on waterfowl.

In 1977 he ordered a “carve your own decoy” kit from an ad in Ducks Unlimited magazine. Two years later at the Virginia Beach Wildfowl Festival, Cameron met Grayson Chesser, a well- known decoy carver and historian. It was a most fortuitous meeting.

At age 12 he took his first drawing lessons in Beaufort. Over the next four years, he spent a week each summer at Chesser’s home in Jenkin’s Bridge, Virginia, learning from the master. Chesser took him to meet Mark McNair, another world-class carver on the Eastern Shore. McNair also offered valuable advice and shared some of the skills he has acquired through the years. One thing he said that Cameron has never forgotten was that the only real difference between a good bird and a great bird is less than a handful of wood shavings.

Snuggling mallard. Hollow cedar, oil, life size.

Cameron made his first decoy, a ruddy duck, at age 13. Five years later he had his first decoy exhibit at the Southeastern Wildlife Exhibition in Charleston, South Carolina. He is quick to admit it takes years of singular focus, hard work and experimentation to produce the quality of flat art (oil painting) and folk art (decoys) with which he can be satisfied. He also feels that art of this type is a life-long learning process—one that never ends. Though he doesn’t talk about it much, those who know Cameron realize that the motivation for his art emanates directly from his life-long passion for waterfowl hunting and for the natural beauty of the swamps, marshes and bays the birds frequent. He is equally passionate about the old decoy makers and the decoy folk art they produced.

Sternboard eagle plaque, 55 inches long, white pine, oil and gold leaf.

After graduation from high school Cameron entered the University of South Carolina with a major in art. Spending a year there, and not finding the opportunity conducive to the progress he needed, he left Columbia to study with William McCollough at the Gibbes Museum of Art in Charleston. McCollough was impressed with Cameron’s ability to paint landscapes and even invited him to stay at his home for part of the year that he studied at Gibbes.

Cameron‘s personal hunting rig on the Maryland marshes of Chesapeake Bay.

In 1989 at age 21, Cameron rolled the dice and moved to the Eastern Shore of Virginia. It was a brave step, but he knew what he was doing. He was following his dream. There the country was turgid with the history of iconic waterfowlers and decoy carvers. Men such as the Ward brothers from Crisfield, Maryland, Nathan Cobb and his family from Cobb’s Island, Virginia, the great Chincoteague carvers and of course Cameron’s friend, Grayson Chesser. There he could follow in their footsteps, carving, painting and duck hunting. He also met Reggie Birch and Pete Peterson, well known contemporary carvers who enjoyed sharing their knowledge and skills with the young dreamer who was driven to turn blocks of wood into beautiful pieces of art for the mantle or for the duck blind.

In 1994 Cameron began doing restoration work on great decoys in need of repair. Handling hundreds of birds by historic figures such as Gus Wilson of Maine, the Ward brothers, the Cobbs, Ira Hudson and the Caines brothers increased his respect for those men and his love of the folk art they produced. Many of their decoys fetch six figure prices on the auction circuit, too steep for the average collector. But Cameron became so adept at producing birds with similar old and classic characteristics that he created a ready and more economical market for these pieces.

Primitive preening Canada goose. Life size, hollow cedar, oil.

He met Adele Miller at a decoy auction in Maine in 1993 and two years later they married. Cameron admits it was a match made in heaven. She appreciates the beauty of nature, loves the decoys and most of all lets him hunt ducks every day of the season. They purchased a 180-acre farm on a tributary between Bullbegger Creek and the Pocomoke River. They named the place Marsh Haven and Cameron paid for it by selling paintings of its marshes and woodlands. It’s isolated, just the way he likes it, so don’t try to find it. There he lives pretty much off the wild game he harvests and the vegetables from his garden. He dismantled a circa-1785 farmhouse and moved it to his land. This he heats with wood that he cuts and splits. The more you dig into his very private lifestyle the more one realizes it harkens back 200 years. He even uses old tools and carves in the same manner as the early masters. He first draws the decoy on paper. “If the look is good there it can be captured on wood,” he says. He then chops it out with a hatchet and refines it with the spokeshave and drawknife.

When Eli Doughty was carving decoys in 1870 he had no television, no computer or cell phone. The same is true with Cameron, at least in his shop where he spends most of his day. He is certainly not anti-social, but the life of the loner is his preference with everyone except his immediate family. In 2002 his son Miles was born and another son, Caleb, arrived four years later. They are both avid outdoorsmen also.

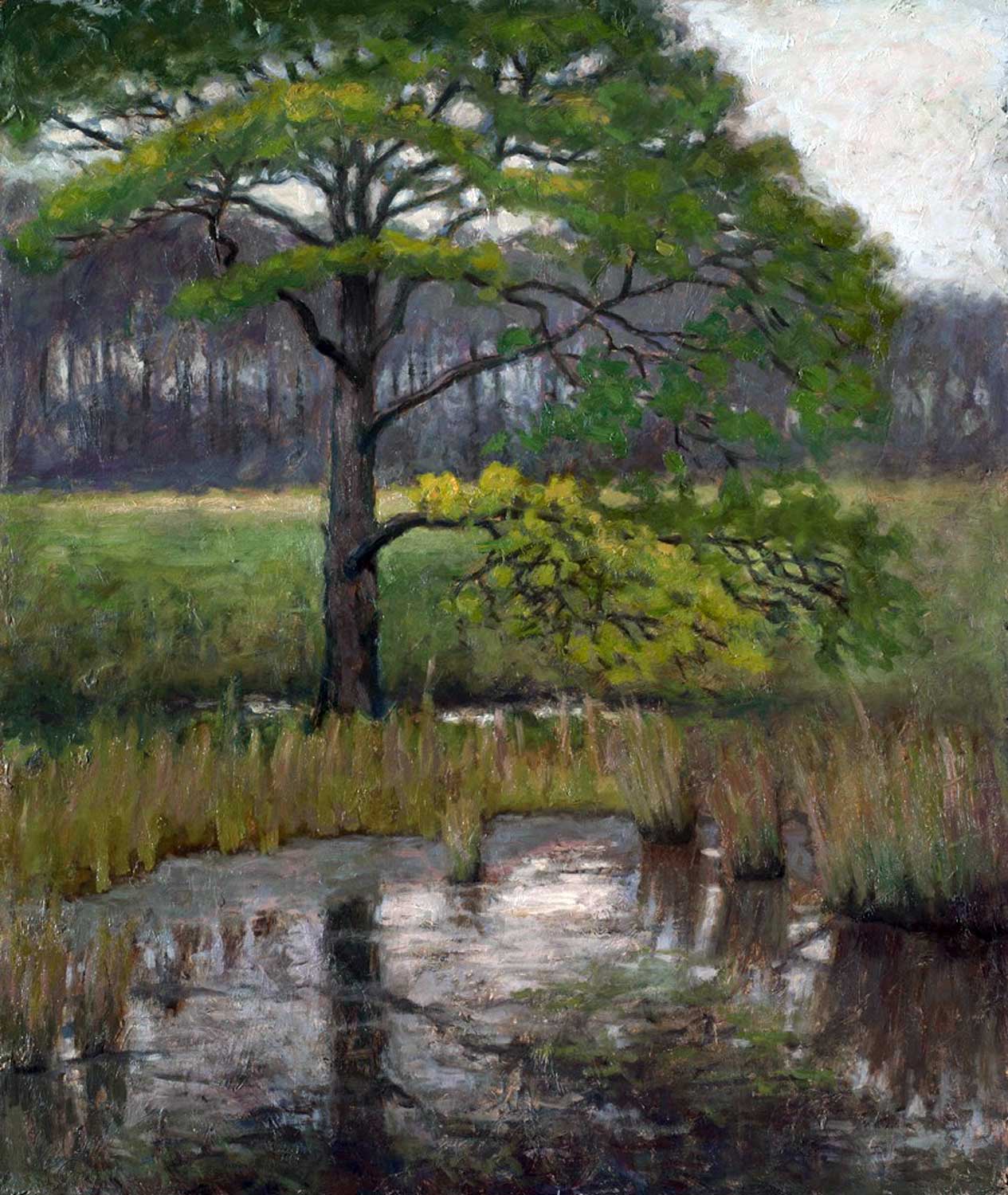

Brackish Glade, oil on board, 22 x 18 inches.

Although Cameron had sold many paintings and decoys previously, he had his first one-man show in 2007. It was a huge success and led to four more singular shows of his paintings over the next four years. He exhibited between 2010 and 2014 at the Newman Galleries in Philadelphia where some of his art sold to foreign destinations including Singapore. He experimented with nature morte art such as hanging game carvings and reopened a genre that had almost disappeared. His hanging duck pieces have been in much demand, a recent carving bringing $27,000 at auction.

Hollow wood duck, life size, cedar, oil.

Cameron met Russell Chatham, one of the country’s best known landscape painters, in Montana in 2009. Six years later, Chatham invited Cameron to visit him at his home in California. Over a period of several days, Chatham shared various techniques he had learned with Cameron. More important, he saw tremendous talent and achievement in Cameron’s art. His significant encouragement was considered a life-changing experience by Cameron.

I asked Cameron which he liked best, carving or painting, but I already knew what his answer would be. “I like them both the same,” he replied. “I go to the carving bench or the painting desk depending on how the mood strikes me and then I focus 100 percent on that piece.” When he needs an escape to clear his mind from the intensity and energy devoted to each rendering, the tractor is nearby. “Mowing and planting game patches offers significant relief and of course if hunting season is open, the ducks take first priority,” explains Cameron. “I never think about business when I’m in the duck blind.”

Green-winged teal still life. Life size, white pine, oil.

In his earlier years, he turned out 75 to 100 pieces (decoys and paintings) a year but now rarely exceeds 20. He spends much more time with each creation, determined to produce that which satisfies him and him alone. He has been carving and painting now for 30 years and has had more than 90 sell-out shows.

It’s obvious the general public who admire and purchase landscape painting and folk art bird carvings feel that Cameron is in a class of his own. But if you ask he is quick to tell you that he is still learning, still striving to be the best that he can be.

As one would expect, Cameron is also a collector of old decoys, particularly from the men whose creations he admires. Those include Gus Wilson, a light-house keeper from Maine, Lem and Steve Ward, Ira Hudson and the Cobb’s Island birds. Some of his favorites are the decoys produced on Hog Island, Virginia, especially those made by Eli Doughty. These Eastern Shore birds with their bold form and subtle weathered paint have influenced Cameron’s work in at least one of the several styles he has developed. Here he blends the look of some of the old masters with his interpretation of the history of the times and the birds they produced.

Resting mallard pair, one piece construction, hollow cedar,oil.

He has spent decades working with paint “almost to madness” to achieve “that look” of a nineteenth century decoy. If you are lucky enough to own one of his creations, you may not know what to do with it. You may want to put it in the water in front of a duck blind. Or like most, it may be destined for the shelf. But one thing is for sure. You will spend a lot of time holding it, admiring the beauty of its form and the rich patina of its paint. And you will marvel at the recreation of a piece of folk art made similar, but even better, than those produced by gifted hands over a century past.