Known for his vivid sporting scenes and evocative still-lifes, Joseph Sulkowski has spent the better part of his life studying techniques of the old masters and applying them to his art. He grinds his own pigments from powdered plants and minerals. Mixes mediums and oils according to recipes developed by Rembrandt and Rubens. Prepares a canvas in an exacting process that requires days of sizing, drying and recoating. All of these are hard-learned skills with centuries-old origins. Many artists, offered the convenience of modern materials, have forgotten these methods of the masters on purpose. There are, after all, much easier ways to produce paintings that will sell.

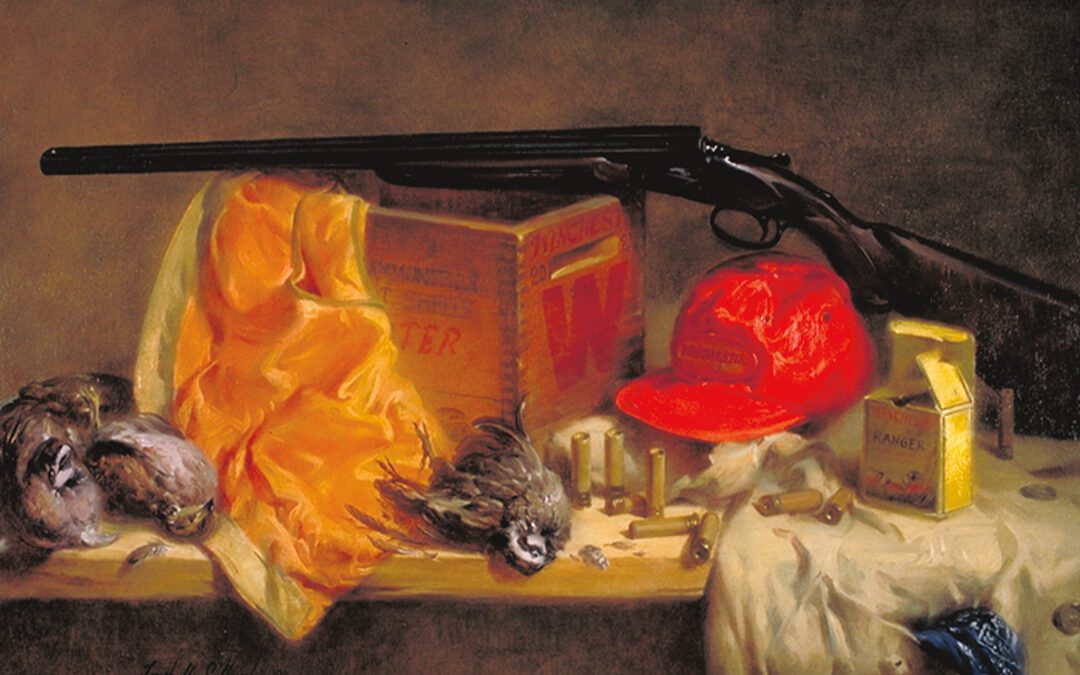

Guns and Trophies

But for Joseph Sulkowski, Art is not about shortcuts. It is a quest for perfection, and the old masters are his paragons. Sulkowski’s devotion to classical style is vital and deep, as essential to his craft as inspiration.

Beagles on the Scent

Born in the industrial heart of Pittsburgh in 1951, Joseph grew up in the little Pennsylvania town of Canonsburg, where his uncle co-owned a barbershop with an aspiring singer named Perry Como. Young Sulkowski had no such musical leanings, but by age five, he knew that he wanted to be an artist. “My parents fostered that talent in us (Joseph’s identical twin, James, is also an accomplished painter). Even as a child, I would see a painting by one of the old masters and think I wonder how he did that? I knew I wanted to be able to do that, too.”

English Pointers

Joseph chose the right path for an artist keen on classical technique. After high school, Joseph and his brother attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts for two years, then enrolled at the Art Students League of New York. There, renowned instructor Frank Mason gave Joseph the foundation he was seeking.

“Mason is probably the greatest American authority on the techniques of the old masters,” Joseph says. “He knew that teaching is a mass of contradictions; that you can’t say, This always happens when you do this.’ So he never taught by formula, but he did know that if you could learn certain universal principles, you could go your own way. He also showed me that you live and die with your art; it guides all you do.”

Dad’s Tackle Box

Sulkowski apprenticed under Mason for his five years at the League. He did little more than stretch canvases and clean studios his first year, but by graduation Joseph was using techniques of the vital heritage kept alive by his mentor.

The intense study paid off for Joseph. Shortly after graduation from the Art Students League, he and James were awarded a commission by the Saudi Arabian government to paint two huge murals depicting Saudi history. The brothers were 28 at the time. “It was like getting a hit record on your first recording,” Joseph laughs. “I feel one of the reasons we got the commission was on the strength of my horses (Sulkowski is an accomplished equine painter.) We worked feverishly for six months; making sketches, sending them to Arabia for approval, painting the pieces, framing them. It is still one of the highlights of my career.”

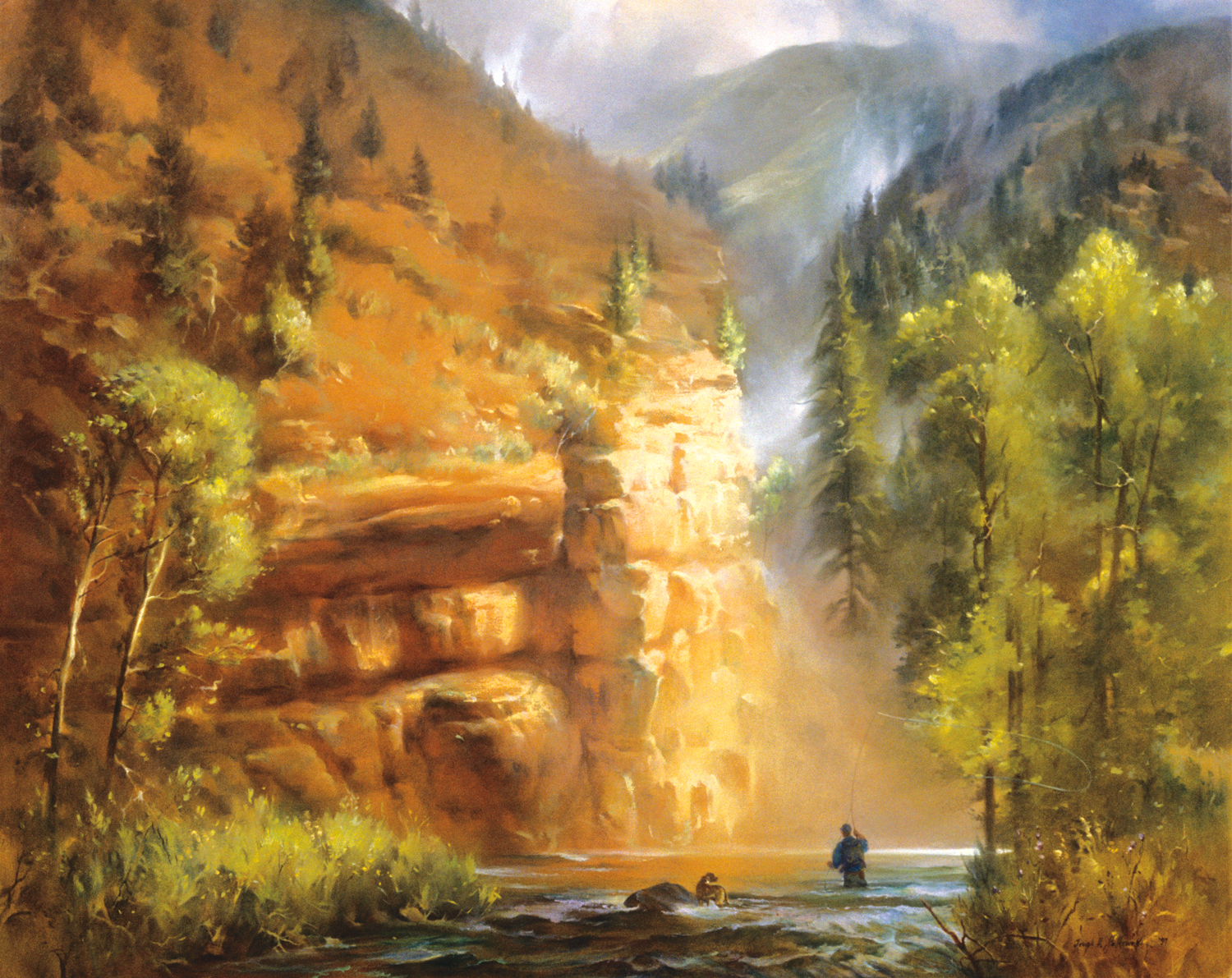

Devil’s Jump

After the Saudi project, Joseph and his wife Beth, also a successful painter, moved to Nashville. The pair have two children, Katie and James. Since his move south, Joseph has devoted more and more time to sporting art. “It seems I am among more sportsmen here,” he says. “I get invited on these wonderful quail hunts and fishing trips. But I’m not a rabid hunter. I love to go, it’s just that when I’m out there, I almost forget about the hunting and get captivated by the scenes – the dogs and horses, the men moving across the landscape. I just love being out there.”

Joseph’s zeal for the outdoors was a gift from his father, an avid fisherman. “He loved to go north into Canada and fish for pike and muskies, large and smallmouth bass,” Joseph remembers. “Some of the fishing tackle and lures I’m painting these days are things I’ve lived with for a long time. There are a lot of memories in those objects.”

Black Labs

Sulkowski is known for still-life paintings that exhibit nostalgia for well-worn gear, days afield with good companions, game taken cleanly and well. How does one wring such emotion from inanimate objects lying on a table? “At least part of it is what you select for your subjects,” he says. “First, I want something with a vintage feel to it; something that’s been around and has character. Then I begin looking at shapes. How do they work together? You not only have to tell a story with objects, they have to complement one another. Then I might put in a fish or bird to the scene. That adds a natural element, so the two worlds – Man and Nature – meet. I enjoy painting scenes that reflect our relationship with the natural world.”

English Setters

Joseph’s sporting scenes likewise reflect that enjoyment. Whether painting the grand traditions of a Southern quail hunt, a retriever with a wounded mallard, or a flyfisherman working a trout pool, Sulkowski explores the complexities of the Man/Nature relationship. “I try to make my human figures and wildlife part of the landscape, rather than the focus. It’s important that we’re seen as part of a bigger picture.”

Fishing the Frying Pan

To achieve such effects, Joseph relies on plein-air painting to capture the mood of an outdoor experience. “I like to paint on location with a field easel,” he explains. ‘I’Il use a nine-by-twelve panel or canvas, and in two hours I’ll have the scene painted with the correct light, colors and effects. If you go any longer than that, your light changes too much. While I’m painting, I’ll make notes and small sketches to bring back to the studio. I can complete most of the rest of the painting by having figures – hunters, dogs, whatever – pose for me in the studio.”

Motherhood

Not surprisingly, Joseph relies little on photography. “I can do some photography when I have to. But I was taught that the camera is a one-eyed liar. It gives only one point of view, and that view is always distorted. I can look at any painting done from a photograph and distinguish it immediately, because it will reflect the distortion of the camera.”

Ignoring a tool like photography shows Joseph’s confidence in classical principles. “Great art goes beyond simple rendering,” he reflects. “And achieving anatomical correctness isn’t all that tough; making a painting live is. The old masters didn’t understand anatomy just so they could understand it. They knew it so they could say, ‘This is a human being. This is how he feels and moves through space.’

“Some artists pay lip service to such training, but Joseph walks his talk. He once constructed a scale-model horse from clay, inserting muscles one at a time. He viewed the exercise as a simple necessity. “Anatomy is science, the twin sister of art. The two constantly go together. The science gives a credibility, a truth, to what you’re trying to paint.”

English Setters in the Mist

While many of Joseph’s idols lived centuries ago, he also admires the work of more recent artists. “Ogden Pleissner and A.B. Frost are among my heroes,” he enthuses. “Their use of light and shadow give their work such great depth and feeling.”

Ah yes, the other twin sisters. It’s nearly impossible to talk painting with Joseph Sulkowski and not have light and shadow dominate the conversation. Like his predecessors, he is obsessed with manipulating their properties. “Even as a young artist I studied light in paintings. What an incredible challenge it is, using very dead pigments to create the illusion of something as vibrant and ever-changing as light. It’s very difficult. When I teach workshops, I tell my students that if the progression of light is working, everything else follows. Watching light move across a figure or the landscape is more important than painting the subject itself.

Golden Head

“Similarly, shadow makes light more apparent. Using shadow properly can make light just glow off a canvas. Shadow has nuances and layers – cobalts, blacks, violets – that are prismatic, but on a darker scale. Plus, shadow creates mood. Jung talked about our ‘shadow side,’ the mystery of human existence. As a painter, you can never be bored with light and shadow.”

English Setter Head

It’s also a safe bet that Joseph’s art will never get tedious. For starters, he plies his brushes in too many genres to ever tire of one. In addition to his sporting art, Joseph paints portraits, landscapes, still-lifes and equine scenes. “Doing other genres brings a fresh perspective to my work,” he says. “You never get caught in a formula of painting wildlife, or landscapes, or people in just one way. The more you learn and paint other subjects, the more spontaneity you have. I know artists who specialize in portraiture, for example. But their paintings get very formulaic; they’re just dead. That’s not great art, to me. Especially when you’re painting someone’s portrait!”

Joseph’s delight in the physical act of painting – grinding pigments, prepping surfaces, laying down a brushstroke – also keeps him fresh and inspired. “Painting should be a joyous process; filling the brush, takin g a swipe at the canvas… A finished painting should look like a lot of fun. It should look juicy and make you stop and say, ‘I wish I could have done that.’ That’s what great art does for me. I prepare the way I do, because it’s a lot like making your own bread; you have more control over the finished product and the effects you want to achieve. In the commercial world the idea is consistency; make them all the same. But paintings should be seen as living things… always fresh and new, never predictable.”

Plantation Quail Hunt

To keep his art vital, Joseph will continue his unique brand of alchemy; combining his fresh, personal vision with the great traditions of art history. His subject matters little – stylish pointing dog, muscular hunting horse, vintage fishing tackle – his goal is the same. “To me the challenge is always, How do I put the world on canvas without giving away all the information? To do in two strokes what I used to do in thirty? You know, two brushstrokes in the right place can take your breath away. What I still don’t know is how to get ever briefer in my depiction of what life is. I know it when I see other artists do it, and I think I’ll know it if I’m lucky enough to do it. I just hope to have a few more years to keep trying.

Contact Joseph Sulkowski and view more of his work at his website: josephsulkowski.com

Click Here to read Joseph Sulkowski’s new feature in Fine Art Connoisseur magazine, detailing his latest project Apokalupsis.

Apokalupsis Bozzetta