Soon we sat down for lunch, and it was a meal typical of what was served when Nilo was built more than a half-century ago. We ate perfectly fried chicken, cole slaw and delicious homemade dill pickles. Lunch was washed down with Arnold Palmers, handmade in the pitchers of lemonade and iced tea. What really caught my attention was the dessert: a simple yet exquisite chocolate pudding pie. I couldn’t remember the last time I had a slice of what was my favorite childhood treat, but it had to have been in the late 1960s.

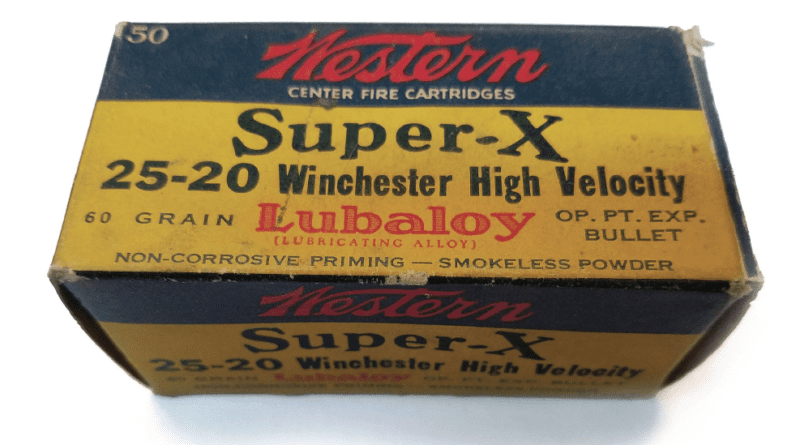

Many of us remember John Olin as a chemical engineer who applied progressive-burning, smokeless powder to paper shotshells for the first time. Olin is the creator of the famous Super-X load. Others remember him for improving upon perfection by creating shotshells with plastic hulls.

While John Olin was a man of many accomplishments, he was most proud of his conservation work at Nilo Farms and his field trial success with King Buck.

Gundog enthusiasts and horse-racers remember John Olin as a competitive animal breeder. Not only did Olin’s Labrador retriever King Buck win back-to-back national championships in 1952 and 1953, but if you follow horse racing, then you’ll remember that his thoroughbred Cannondale won the 1974 Kentucky Derby. Rocket scientists nod at the name Olin for he supplied monomethyl hydrazine fuel that was used in the Space Shuttle Columbia for directional control during its 1981 flight. Olin was quite literally a household name for he also created a bleach powder that made laundry clean and bright.

There didn’t seem to be much that Olin could not do. While his Winchester Repeating Arms Company produced Model 12s, 21s and 70s, Olin Corporation made solar panels 40 years before they became popular, created fertilizer for commercial agricultural ranches and still had time to make Beach Nut Life Savers. You remember them, right? They were the rolls of candy you got in your sack at Halloween.

Olin was a businessman, but at his core, he was a sportsman. He was equally adept at fishing for Atlantic salmon on the Moisie River, hunting Red Hills quail on his Albany, Georgia, plantation and shooting skeet, trap and pheasants at his modest Nilo Farms. And while those pastimes may seem toney, his family history is fascinating.

The first Olin to arrive in America did so in 1678, but not by choice. His name was John, too, and he was shanghaied in Wales and pressed into service on a British merchant ship. The ship arrived in Boston Harbor three months later, and when it did, Olin had an epiphany. He believed there had to be a better way to live his life and a better place to do it. No sooner did he step off the vessel than he high-tailed it to East Greenwich, Rhode Island.

Olin life as we know it today began emerging two centuries later at the generation six level. The architect was Franklin W. Olin, John’s father, and he laid a strong business foundation shortly after graduating from Cornell University in 1886 with an engineering degree. Franklin’s first invention was mundane, but it was revolutionary: a sock-weaving machine. His machine and technique solved a common and irritating problem: the wearing out of the toes and heels in an ordinary pair of socks. His business exploded, leading him to explore other under-served markets. He found one in the expanding sport-shooting market around the turn of the century.

To provide shooters with shells, Franklin followed the mantra: “the whole is the sum of the parts.” He began by purchasing a gunpowder mill in Pompton Junction, New Jersey, then bought 51 percent of the shares in the Equitable Powder Manufacturing Company. His pièce de résistance, however, came in 1898 when he created a shotgun shell manufacturing company.

Once Olin’s Western Cartridge Company had created a strong demand for shotshells, he proceeded to acquire a company that made targets. Thus was born the Western Trap and Target Company, which made a product known to us all: White Flyer clay pigeons.

Sportsmen may not know about Olin’s powder bleach laundry detergent, but they are certainly familiar with his Super X bullets and shotshells.

Franklin Olin went on to buy or launch companies that made a variety of components including primers, brass, wads, shot and shells and oversaw the building of machinery that resulted in profitable production. His shells were widely regarded as excellent, and one report called the quality of his primers “industry-best.” At their worst, they reported one misfire per 10,000 rounds and at their best, a mere one misfire per 100,000!

John inherited the house that Franklin built, but his Olin spirit caused him to expand in a visionary way. John embarked on what we now call a “roll up,” which combined the Western Cartridge Company, Winchester Repeating Arms Company, the United States Cartridge Company, the Equitable Powder Manufacturing Company, the Kalunite and Aluminum Division and a Cellulose Research Corporation—all into Olin Industries.

World Wars I and II represented boom times for the company, but to avoid peacetime manufacturing slumps, Olin diversified into chemicals, agriculture, pharmaceuticals, paper, cellophane and more. But his love for hunting remained at the core, and he became aware that open space, suitable habitat and ample game needed a champion. He rose to that occasion as if it were his calling.

John Olin’s contributions to sport hunting were manifold. They began when he served as Western Cartridge Company’s delegate to the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers Institute (SAAMI). SAAMI’s purpose was to identify future markets for firearm and ammunition manufacturers, and recreational hunting and shooting were foremost.

In the 1920s, Olin observed depleted numbers of wild game. Some losses came from unregulated market and subsistence hunting while others came as a result of habitat loss at the expense of the industrialization of agriculture. The 1930s’ dust bowl and depression worsened game stocks, and by the 1940s, many game species were in a beleaguered state.

As chairman of SAAMI’s Committee on Restoration and Protection of Game, Olin directed Aldo Leopold to write his classic Game Survey of the North Central States. Many of Leopold’s findings were used to develop “An American Game Policy,” which served as the first blueprint for game management. This science-based treatise ushered in a new era in the search for proven techniques that continues today.

If you’re interested in walking in the shadows of John Olin’s footsteps, then plan a pheasant hunt at Nilo Farms.

Olin urged Leopold to continue forward and write “Game Management,” the gold standard used by modern conservationists. He hired celebrated outdoor writer Nash Buckingham as a bobwhite quail advisor along with Herbert Stoddard, the famous Georgia quail biologist. The men tested quail management practices on Olin’s Albany, Georgia plantation where one quail per acre was the norm. In short order, their methods doubled that number to two quail per acre.

Olin funded the Game Conservation Society, a leading conservation organization of the day that focused on supplemental game management programs for commercial use. The GCS was incorporated into More Game Birds in America, which eventually became Ducks Unlimited. Olin also worked with the Clinton Game School in New Jersey to create a training program for men professionally engaged in game breeding and management. Many of these men became the first trained employees of state fish and game departments.

John Olin championed the newly formed Pittman-Robertson Federal Aid in the Wildlife Restoration Act, which portioned taxes spent on sporting arms and ammunition to support game management and open space initiatives.

By 1952, Olin realized that preserves would play an important part in the future of hunting. He acquired 640 acres spread across three contiguous tracts of marginal farmland near Brighton, Illinois. His Nilo Farms included a modest ranch-style house, pheasant fields, a kennel, and skeet and trap ranges. Everything of importance to a hunter, from fields to dogs to firearms and shells was top shelf. The land was cultivated with corn, milo and soybeans to a state of perfection.

When you’re done shooting, be sure to visit the statue of King Buck that overlooks the property.

Nilo Farms became a testing ground for the viability of released bird hunts that rivaled wild birds, and it worked. Released bird hunting began to expand dramatically after Olin published “Shooting Preserve Management— The Nilo System.” The inclusion of the word “preserve” was unique to the 1966 publication, and it’s still in use today.

Dogs are integral to bird hunting, and Olin was a devout Labrador retriever man. As with every other aspect of his life, Olin sought to create the best and, after decades of careful genetic study, successful breeding and training, his efforts were rewarded with King Buck.

Trained by T.W. “Cotton” Pershall, King Buck won back-to-back national championships in 1952 and in 1953, and is the only retriever to compete in 83 out of 85 series in the National Championship. In today’s world, he’d be known as the GOAT, the greatest of all time. King Buck’s success earned him an iconic place on the Federal Migratory Waterfowl Stamp (1959-60), and he’s the only dog to appear on a duck stamp. Olin loved dogs and his collection of certificates, silver plates and silver cups register CH and RUCH victories.

To see the sum of John Olin’s many achievements, head to Nilo Farms for a hunt. You’ll walk where he walked and shoot on his skeet and trap ranges complete with freestanding shell box holders at every station. It’s a throwback to the Golden Age of Shooting where you can experience the life of a man who contributed so much to what we enjoy today. It’s all great in John Olin’s world, right down to the fried chicken and chocolate pudding pie.

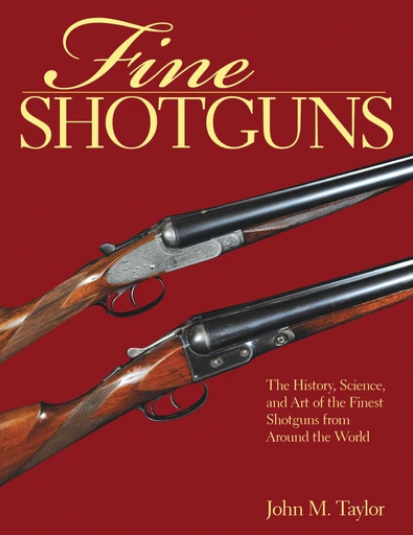

Firearms expert John Taylor offers a global view of shotguns using photographs and descriptions of guns from the U.S. and many European countries. Sections include how to care for and store your gun, available accessories, and travel cases. Buy Now

Firearms expert John Taylor offers a global view of shotguns using photographs and descriptions of guns from the U.S. and many European countries. Sections include how to care for and store your gun, available accessories, and travel cases. Buy Now