The hurricane roared through like a runaway train, like a Seaboard freight with a stuck throttle.

Fifteen inches of rain in fifteen hours, wind a-hundred-plus-Jesus, tornados on the back side, it tore hell out of the piney ridges and swamp-ground hardwoods in between.

Three hundred of us way out here on this sore thumb against the sea; one-third of us took our chances. Every man parked his tractor in the middle of a field; every man laid up fuel, dug out his log chains and sharpened his saw. Everybody had a job. I fired the generator to keep the beer cold, the modem hot. So long as the Internet worked, the world would know we were still alive.

It was a noble endeavor but a mite hard on the nerves.

That was right after Mrs. Clinton called us deplorable. We shook our heads, scratched our fannies, walked around in circles as we thunk it through. Then we named ourselves the Daufuskie Deplorable One Hundred. I slapped it up on Facebook, the papers got wind of it and the governor was furious.

How dare we defy her mandatory evacuation? She called us out on national TV, said we all would drown. She ordered up one last ferry run, a 40-passenger boat, too small. She mobilized a National Guard posse to round us all up, but by then it was too late for the choppers to fly.

There commenced a mighty howling in the heavens, a great heaving of the sea, ship-mast pines laid like jackstraws upon a great snarl of power lines, an eight-foot surge right at a full moon flood-tide, docks ripped up, boats adrift, sunk outright or blown way up into the trees. The eye right over the shack at 2 a.m., so we missed it all.

A damn shame to waste a perfectly good hurricane on the dark.

They called it a class two, but it was actually a class three, 130 in gusts. Dickie’s coonhound sprained a leg, and Miss Raya broke her arm in a roller-rink after evacuating to Atlanta. One house lost to a pole-axe pine, two to the surf, but that’s about it.

And it’s a damn shame to annoy your governor, but we did. It’s deep down in November now; the freezer ain’t empty, but you can see the bottom. Time to go down to Barge Landing at the first flush of dawn; time to light one last delicious cigarette and read the smoke, then sneak upwind, easing along at about a mile an hour toting a 12-bore stuffed with double ought. The deer will bust loose almost from beneath your feet and you can shoot them on the rise like quail. But it’s tough walking among all the blow-downs, and forget quiet, it’s like wading through a pile of Venetian blinds. But that’s where the deer are—feasting on wind-fall acorns and tender top branches.

Will this be the first year in 50 I will not kill a deer?

Running? I reckon not. I didn’t run from that storm, I never ran from nothing, ’cepting a warrant, a bear and a woman or two.

So maybe I ought to call it a pilgrimage. I lit out for Darlington, South Carolina, to meet Jim Kelly, the man who brought Bo Whoop back from the dead.

You likely know about Bo Whoop, the Super-Fox magnum 12 specially built for Nash Buckingham by Bert Becker, Ansley Fox’s best barrel man, Bert Becker’s and Mister Buck’s name stamped on the barrel. It had no safety, as Mister Buck thought a safety provided a false sense of security. Three-inch chambers with long forcing cones, it was over-bored and over-choked, with 1 7/8 ounces of #4 shot, reputed to pattern an astounding 90 percent at 40 yards and to make consistent, clean kills at 60.

If you were next to Mister Buck in the blind, it sounded like an ordinary 12, maybe a little louder. But if you were on the far side of the pond, the gun said “bo-whoop,” whenever Mister Buck cut loose.

Mister Buck was an odd bird by all accounts. He would not hunt without a tweed jacket and a tie. He was a regular contributor to the sporting press, a bestselling author of nine books, but he never owned a house or a car, or even learned to drive. He was notoriously forgetful, sometimes even dis-remembering the name of his own dog.

On December 1, 1948, Mister Buck and a hunting buddy were stopped by a warden after coming up from a stand of flooded Arkansas timber. When the warden learned he just stopped the most famous duck hunter in America, he asked to see Bo Whoop. He pawed and drooled, laid the gun on the rear fender and took his leave. Some miles down the road, Mister Buck remembered the shotgun.

They backtracked, searched the road and the ditches, placed ads in the local papers, but he never saw Bo Whoop again. And it remained lost for 57 years until a young man from Savannah walked into Darlington Gun Works and asked about replacing the cracked stock on a finely appointed old Super Fox he had inherited from his grandfather.

At the request of a client, Jim Kelly restocked Buckingham’s Bo Whoop at his Darlington Gun Works in Darlington, South Carolina. The fabled firearm disappeared once again before it was consigned to James D. Julia auction house. Photograph Courtesy Ducks Unlimited

Jim Kelly knew he was looking at one of the most famous shotguns in American history. A gold-inlayed Parker made for Czar Nicolas II, but never delivered before the Bolsheviks shot him and his family, fetched up $287,000. Teddy Roosevelt’s Fox sold for more than $800,000, and Bo Whoop had to be a close third. Considering the backstory, Kelly tried to dissuade the young man from restocking, as it might be more valuable broken, but to no avail. Kelly restocked the gun, and it disappeared once again, but eventually medical problems and associated expenses prompted the young man to offer it for sale.

The gun was consigned to James D. Julia, but first Julia had to determine who actually owned Bo Whoop. He discovered a letter in which Mister Buck told a friend the loss had been insured. So then some unknown insurance company likely had claim to it. Julia estimated the 1948 value of Bo Whoop to be $400 and let it be known that he would gladly pay that, plus interest, should a subsidiary company claim ownership. None did, and the gun was sold to Hal Howard, a retired stockbroker and Mister Buck’s godson, for a little over $200,000. Then Howard donated the gun to Ducks Unlimited, where it was on display at their Memphis headquarters, built in a field where Mister Buck once hunted doves. But first DU sent the gun afield once again with three writers under the agreement they would document the event with photos and video. Three men shot it, and nobody missed.

Sweet. And there I was standing at Jim Kelly’s counter, but I had not come empty-handed. I had brought along a battered but beloved LC Smith Long Range Special twelve. Built just after the Great War in the days before the three-inch magnum, with 32-inch barrels, long forcing cones, and long, tapered chokes—full and full—it was specially tuned to handle the heaviest loads then available: 1 3/8 ounces of #4 shot. It was a gift from a lifelong friend that came with a single stipulation: I would have the gun restored. A promise made is a debt unpaid, the poet says, and now I was ready to set things right.

I signed the work order and turned toward home with clear head and heart, ready now to kill a deer.

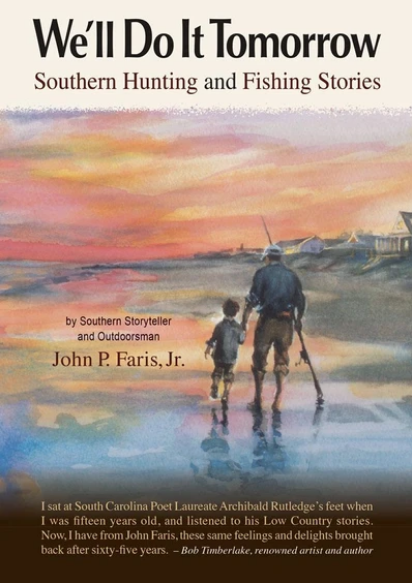

We’ll Do It Tomorrow: Southern Hunting and Fishing Stories Reviewed & endorsed by Jim Casada of Sporting Classics who said, “This is relaxed literature on the outdoors in the vein of Babcock, Rutledge and Ruark in his ‘Old Man’ pieces.” Buy Now

We’ll Do It Tomorrow: Southern Hunting and Fishing Stories Reviewed & endorsed by Jim Casada of Sporting Classics who said, “This is relaxed literature on the outdoors in the vein of Babcock, Rutledge and Ruark in his ‘Old Man’ pieces.” Buy Now